July, 21 2010, 10:30am EDT

NACLA Condemns State Department's Denial of a Visa to Colombian Journalist Hollman Morris

NEW YORK

The North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) denounces the State

Department's decision to deny a visa to Colombian TV journalist Hollman

Morris. Morris was slated to receive the Samuel Chavkin Award for

Integrity in Latin American Journalism, awarded by NACLA in recognition

of his brave and uncompromising coverage of the armed conflict in

Colombia. NACLA originally planned to hold the Chavkin Award ceremony on

June 8 but had to postpone it when it became clear that the U.S.

Embassy was taking much longer than usual to renew Morris's tourist

visa. The government later denied Morris a student visa that would allow

him to take up a prestigious Nieman Foundation fellowship to study at

Harvard University.

The visa denial appears to be intended to punish Morris for his

reporting on the Colombian peace and human rights movement. According to

the "refusal worksheet" provided to Morris by the State Department, the

visa was denied under section 212(a) of the Immigration and Nationality

Act, which, as amended by section 411 of the USA Patriot Act, bars

visas from being granted to any foreigner who has used his or her

"position of prominence" to "endorse or espouse terrorist activity, or

to persuade others to support terrorist activity or a terrorist

organization."

In denying Morris a visa on these grounds, the State Department joins

the Colombian government in tarring Morris as a "publicist for

terrorism," in the words of Colombian president Alvaro Uribe. Since

coming to power in 2002, Uribe has often portrayed Colombia's human

rights community, peace activists, and others who favor a negotiated

peace settlement as in league with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of

Colombia (FARC), the country's more than 40-year-old guerrilla

insurgency and a U.S.-designated terrorist organization. Documents made

public in April show that Colombia's Administrative Department of

Security (DAS), a domestic intelligence agency under the command of the

presidency, in 2005 launched what it called a "smear campaign at the

international level" against Morris.

"Negotiate the suspension of [U.S.] visa" appears on the agency's list

of tactics against Morris (which also included the dissemination of

defamatory materials, wiretaps, and physical surveillance). Morris was

targeted as a part of a broader dirty tricks program aimed at silencing

and intimidating government critics; almost two dozen former DAS

officials are awaiting trial on criminal conspiracy charges in

connection with the scandal. Although no evidence has appeared to

suggest that a request from Colombian intelligence directly led the

State Department to deny the visa, the decision nonetheless exactly

coincides with one of the smear campaign's goals.

The most recent accusations against Morris came in February 2009, when

Colombian president-elect Juan Manuel Santos, then Uribe's minister of

defense, joined Uribe in publicly accusing Morris of working with the

FARC. These denunciations came after Morris filmed last-minute

negotiations led by Colombian senator Piedad Cordoba, together with

members of a Colombian peace group and the Red Cross, over the release

of four hostages held by the FARC. The negotiations proved successful,

and the FARC released the hostages. The footage of this was included in

Colombia, la hora de la paz, a documentary later aired on the History

Channel's Latin America network. According to Uribe, Morris's coverage

amounted to pro-guerrilla propaganda, and his contact with the FARC in

his capacity as a journalist amounted to collaborating with them.

Why would the Colombian president resort to calling a well-respected

journalist, whose family has endured numerous death threats, a

terrorist? Because news coverage of successful FARC negotiations is

deeply embarrassing to the Uribe government, whose Bush-style "war on

terror" is premised on the idea that the FARC cannot be negotiated with;

that diplomacy with the guerrillas, who number in the thousands and

control an estimated 30% to 40% of Colombian territory, is misguided;

and that the only solution to the conflict is to crush the enemy, waging

a total war funded by the U.S. government to the tune of $7.3 billion

since 2000.

No credible evidence of Morris's involvement with terrorism has ever

come to light, nor has the Colombian government ever charged him with a

crime. Indeed, his only "crime" has been to cover and take seriously the

Colombian peace and human rights movement-as well as to doggedly expose

the corruption in the Colombian government, the grave human rights

abuses committed by the country's security services, and the political

influence of paramilitary groups. Moreover, the idea that a journalist's

contact with combatants in an armed conflict automatically amounts to

supporting or endorsing them is contrary to mainstream understandings of

journalistic practice.

As Carol Rose noted in a blog entry on the Boston Globe's website,

Morris's visa denial recalls the McCarthy-era practice of "ideological

exclusion," codified in the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act, in which the

United States barred entry to artists and intellectuals thought to be

tainted with Communism-notable examples included Graham Greene, Charlie

Chaplin, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, Doris Lessing, and

Pablo Neruda. U.S. journalists during this time also faced limits on

their freedom to travel; one of them was Samuel Chavkin, the late

investigative journalist and Latin America correspondent in whose name

NACLA was to bestow an award on Morris.

There is a powerful historical resonance between Chavkin and Morris. In

1951, after two decades of reporting for a variety of news

outlets-including the U.S. Army papers Yank and Stars and

Stripes-Chavkin tried to renew his passport so that he could travel to

Southeast Asia to cover hunger for the humanitarian group CARE. The

State Department refused, saying only that granting him a passport would

"not be in the best interests of the United States." Chavkin did not

get his passport back until 1960, after enduring almost a decade of

forced retirement.

The Chavkin award, established by his family, is meant to encourage

Latin American journalists to expose injustice and oppression, and to

document struggles for social justice and democracy in Latin America. We

can think of no better way to honor Chavkin's legacy, and that of all

other journalists whom governments have tried to silence, than to award

Hollman Morris the Chavkin prize, in absentia if necessary, on a date to

be announced in October.

See nacla.org/node/6670

for a hyperlinked version of this statement.

LATEST NEWS

Historic Number of Democratic Reps Vote Against Unconditional Aid to Israel

"Most Americans do not want our government to write a blank check to further Prime Minister Netanyahu's war in Gaza," a group of nearly 20 of the 37 no-voting lawmakers said.

Apr 20, 2024

Nearly 40 House Democrats voted against a measure to send around $26 billion more to Israel as it continues its war on Gaza that human rights experts have deemed a genocide.

While the Israel Security Supplemental Appropriations Act passed the Republican-led House by a vote of 366-58, party insiders said it was significant that such a large number of Democrats had opposed it, with more centrist lawmakers joining progressives who have called for a cease-fire since October.

"Despite the weapons aid package passing, this is the largest number of Democratic lawmakers to vote against unrestricted weapons aid for Israel in recent memory," senior Democratic strategist Waleed Shahid observed on social media.

"If Congress votes to continue to supply offensive military aid, we make ourselves complicit in this tragedy."

Human rights lawyer, lobbyist, and former Democratic National Committee committeewoman Yasmine Taeb posted that it was "incredibly significant that 37 Democrats voted NO and rejected AIPAC's role and influence in the party."

Senior Democrats who opposed the funding included Reps. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), Maxine Waters (D-Calif.), Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas), Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.), Jim McGovern (D-Mass.), and Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-N.J.)

The bill earmarks around $4 billion for Israel's missile defense systems and more than $9 billion for humanitarian aid to Gaza, according toThe Associated Press. However, while lawmakers approved of individual expenditures, they balked at giving more unconditional military aid to the far-right government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

"U.S. law demands that we withhold weapons to anyone who frustrates the delivery of U.S. humanitarian aid, and President Biden's own recent National Security Memorandum requires countries that use U.S.-provided weapons to adhere to U.S. and international law regarding the protection of civilians," McGovern said in a statement explaining his vote. "To date, Netanyahu has failed to comply. It's time for President Biden to use our leverage to demand change."

Nearly 20 Democratic representatives released a joint statement explaining their vote. They were McGovern, Doggett, Watson Coleman, Joaquin Castro (D-Texas), Nydia Velázquez (D-N.Y.), Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), Becca Balint (D-Vt.), Greg Casar (D-Texas), Mark Takano (D-Calif.), Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), Judy Chu (D-Calif.), Hank Johnson (D-Ga.), André Carson (D-Ind.), Jesús "Chuy" García (D-Ill.), Jonathan Jackson (D-Ill.), and Jill Tokuda (D-Hawaii).

"This is a moment of great consequence—the world is watching," the lawmakers wrote. "Today is, in many ways, Congress' first official vote where we can weigh in on the direction of this war. If Congress votes to continue to supply offensive military aid, we make ourselves complicit in this tragedy."

The lawmakers clarified that their no votes were specifically "votes against supplying more offensive weapons that could result in more killings of civilians in Rafah and elsewhere."

While they acknowledged that Israel had a right to defend itself, they argued that its greatest security would come from a cease-fire that enabled the release of hostages, humanitarian aid to enter Gaza, and peace negotiations to begin in earnest.

"Most Americans do not want our government to write a blank check to further Prime Minister Netanyahu's war in Gaza," they concluded. "The United States needs to help Israel find a path to win the peace."

Mark Pocan (D-Wis.), who also voted no, said that he "could not in good conscience vote for more offensive weapons to be given to Israel to be used in Gaza without any conditions attached."

Pocan further called the "devastation inflicted upon innocent civilians in Gaza" "unjustifiable" and argued that "further arming Netanyahu and his extreme coalition could only lead us to a wider conflict in the Middle East."

In a speech on the House floor, Lee also criticized the bill for failing to restore funding to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, which provides the bulk of aid to the Gaza Strip. The U.S. paused funds for the agency following Israeli allegations that 12 of its employees participated in Hamas' October 7 attack, but other nations have since restored funding as the veracity of these allegations has been called into question.

"This is a grave abdication of U.S. humanitarian obligations," Lee said. "It is simply nonsensical to provide badly needed humanitarian assistance while simultaneously funding weapons that will be used to make the humanitarian crisis in Gaza worse."

She added, "The United States taxpayers should not be funding unconditional military weapons to a conflict that has created a catastrophic humanitarian disaster."

The bill sending funds to Israel was only one of several measures passed on Saturday as part of a $95 billion foreign spending package that will also provide a long-delayed approximately $61 billion for Ukraine in its war with Russia and around $8 billion to counter China in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Among the bills passed Saturday was one banning popular social media app TikTok in the U.S. if the Chinese company that owns it refuses to sell, theAP reported further.

The package will now go to the U.S. Senate, which could pass it as early as Tuesday. President Joe Biden has promised to sign the measures as soon as he receives them.

Keep ReadingShow Less

'Shame': Bill Including Warrantless Spying Expansion Passes Senate, Becomes Law

"The Make Everyone A Spy provision will be abused, and history will know who to blame," one civil liberties advocate said.

Apr 20, 2024

The U.S. Senate voted early Saturday morning to reauthorize Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act for two years, including a "poison bill" amendment added by the U.S. House that critics and privacy advocates dubbed the "Make Everyone a Spy" provision.

The reauthorization, officially called the Reforming Intelligence and Securing America Act, passed the Senate 60-34 despite the more than 20,000 constituents who called opposing the measure, which the Brennan Center for Justice said would enable "the largest expansion of surveillance on U.S. soil since the Patriot Act." President Joe Biden then signed the bill into law later Saturday.

"It's over (for now)," Elizabeth Goitein, the co-director of the Brennan Center's liberty and national security program, said on social media. "A majority of senators caved to the fearmongering and bush league tactics of the administration and surveillance hawks in Congress, and they sold out Americans' civil liberties."

"There is no defense for putting a tool this dangerous in the hands of any president, and doing so is a historic mark of shame."

Section 702 is the provision that allows U.S. intelligence agencies to spy on non-U.S. citizens abroad without a warrant. Currently, they are able to do so by acquiring communications data from electronic communications service providers like Google, Verizon, and AT&T. The existing provision has already been widely abused and criticized, as the communications of U.S. citizens are often caught up in the searches.

However, an amendment added by Reps. Mike Turner (R-Ohio) and Jim Himes (D-Conn.) redefined electronic communications service providers to include any "service provider who has access to equipment that is being or may be used to transmit or store wire or electronic communications."

Former and current U.S. officials toldThe Washington Post that the new language was intended to apply to data cloud storage centers, but civil liberties advocates like Goitein warn it could be used to compel any business—such as a grocery store, gym, or laundry service—to allow the National Security Agency (NSA) to scoop up data from its phones or computers.

"The provision effectively grants the NSA access to the communications equipment of almost any U.S. business, plus huge numbers of organizations and individuals," Goitein wrote on social media early Saturday. "It's a gift to any president who may wish to spy on political enemies, journalists, ideological opponents, etc."

"It is nothing short of mind-boggling that 58 senators voted to keep this Orwellian power in the bill," Goitein wrote.

Privacy advocates also criticized how the vote was forced through, as the Biden administration and Senate leaders including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Mark Warner (D-Va.) had emphasized that Section 702 was set to expire on Friday and raised alarms about what would happen to national security if the Senate allowed this to happen. However, as The New York Times pointed out, a national security court ruled this month that the program could run for another year even if the law expired.

"The headlines of state-aligned media screech and crow about the nefarious designs of your fellow citizens and the necessity of foreign wars without end, but find few words for a crime against the Constitution."

"Senator Warner and the administration rammed this poison pill through the Senate by fearmongering and saying things that are simply false," Demand Progress policy director Sean Vitka said in a statement. "There is no defense for putting a tool this dangerous in the hands of any president, and doing so is a historic mark of shame."

Once Biden had signed the bill, Vitka added on social media: "Shame on the leaders who let House Intelligence veto reform in the darkness, and ram through terrifying surveillance expansions on the basis of outright lies. The Make Everyone A Spy provision will be abused, and history will know who to blame."

Goitein used similar language to condemn the vote.

"This is a shameful moment in the history of the United States Congress," she said on social media. "It's a shameful moment for this administration, as well. But ultimately, it's the American people who pay the price for this sort of thing. And sooner or later, we will."

NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden added, "America lost something important today, and hardly anyone heard. The headlines of state-aligned media screech and crow about the nefarious designs of your fellow citizens and the necessity of foreign wars without end, but find few words for a crime against the Constitution."

Schumer announced a deal late Friday to vote on a series of amendments to the bill clearing the way toward its passage, according toTheHill. However, all five amendments that would have added greater privacy protections were voted down, The Washington Post reported.

"If the government wants to spy on the private comms of any American, they should be required to get approval from a judge, as the Founding Fathers intended."

These included an amendment from Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) to require a warrant and another from Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) to remove the House language expanding the entities who could be forced to spy, according to Roll Call. The amendments were rejected 42-50 and 34-58 respectively.

"Congress' intention when we passed FISA Section 702 was clear as could be—Section 702 is supposed to be used only for spying on foreigners abroad. Instead, sadly, it has enabled warrantless access to vast databases of Americans' private phone calls, text messages, and e-mails," Durbin posted on social media.

"I'm disappointed my narrow amendment to protect Americans while preserving Section 702 as a foreign intel tool wasn't agreed to," Durbin continued. "If the government wants to spy on the private comms of any American, they should be required to get approval from a judge, as the Founding Fathers intended."

Wyden said in a statement: "The Senate waited until the 11th hour to ram through renewal of warrantless surveillance in the dead of night. But I'm not giving up. The American people know that reform is possible and that they don't need to sacrifice their liberty to have security. It is clear from the votes on very popular amendments that senators were unwilling to send this bill back to the House, no matter how common-sense the amendment before them."

Wyden was not the only one who pledged to keep fighting government surveillance overreach.

Vitka praised Durbin and Wyden, as well as other legislative privacy advocates including Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), Warren Davidson (R-Ohio), Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.), Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.), and Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), saying the lawmakers had "built a formidable foundation from which we will all continue to fight for civil liberties."

Goitein also said the opposition of outspoken senators and concerned citizens were "silver linings."

"Because of the heat we were able to bring, we extracted some promises from the administration and the Senate intelligence committee chair. I do think they'll be forced to make SOME changes to mitigate the worst parts of the law, which they can do by including those changes in an upcoming must-pass vehicle, like the National Defense Authorization Act," she added.

The American Civil Liberties Union also responded to the vote on social media.

"Senators were aware of the threat this surveillance bill posed to our civil liberties and pushed it through anyway, promising they would attempt to address some of the most heinous expansions in the near future," the organization said. "We will do everything in our power to ensure these promises are kept."

Keep ReadingShow Less

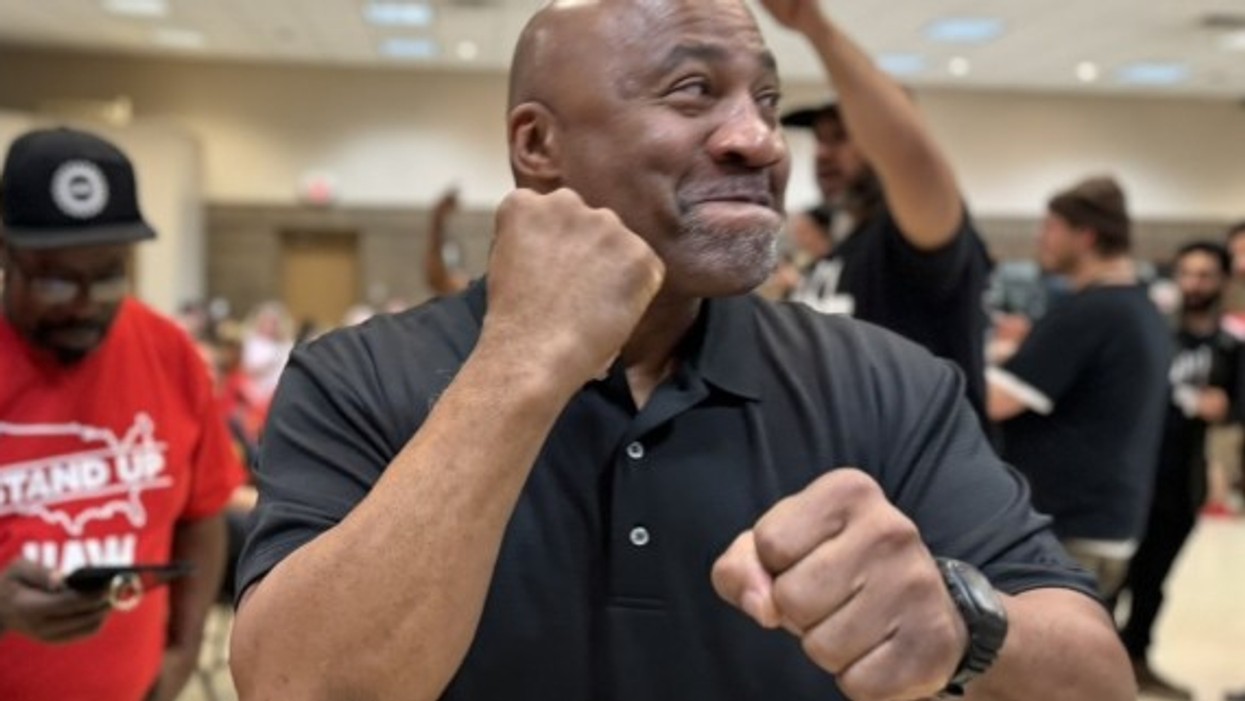

'You All Moved a Mountain': Tennessee Volkswagen Workers Vote to Join UAW

"We're poised to be the first domino of many to fall," one worker at the Chattanooga plant said.

Apr 20, 2024

Workers at a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, became the first Southern autoworkers not employed by one of the Big Three car manufacturers to win a union Friday night when they voted to join the United Auto Workers by a "landslide" majority.

This is the first major victory for the UAW after it launched the biggest organizing drive in modern U.S. history on the heels of its "stand up strike" that secured historic contracts with the Big Three in fall 2023.

"Many of the talking heads and the pundits have said to me repeatedly before we announced this campaign, 'You can't win in the South,'" UAW president Shawn Fain told the victorious workers in a video shared by UAW. "They said Southern workers aren't ready for it. They said non-union autoworkers didn't have it in them. But you all said, 'Watch this!' And you all moved a mountain."

"This incredible victory for labor will transform Tennessee and the South!"

According to the UAW's real-time results, the vote tally now stands at 2,628—or 73%—yes to 985—or 27%—no. Voting at the around 4,300-worker plant began Wednesday.

The Chattanooga workers announced their current union drive in December 2023. Friday's victory follows two failed unionization attempts at the plant in 2014 and 2019.

"We saw the big contract that UAW workers won at the Big Three and that got everybody talking," Zachary Costello, a trainer in VW's proficiency room, said in a statement. "You see the pay, the benefits, the rights UAW members have on the job, and you see how that would change your life. That's why we voted overwhelmingly for the union. Once people see the difference a union makes, there's no way to stop them."

The union's win comes despite the opposition of Republican Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee.

"Today, I joined fellow governors in opposing the UAW's unionization campaign," Lee said on social media Tuesday. "We want to keep good-paying jobs and continue to grow the American auto manufacturing sector. A successful unionization drive will stop this growth in its tracks, to the detriment of American workers."

However, Tennessee State Rep. Justin Jones (D-52) celebrated the win.

"Watching history tonight in Chattanooga, as Volkswagen workers voted in a landslide to join the UAW," he wrote on social media Friday night. "Despite pressure from Gov. Lee, this is the first auto plant in the South to unionize since the 1940s. This incredible victory for labor will transform Tennessee and the South!"

Other national labor leaders and progressive politicians also congratulated the Chattanooga workers.

Lee Saunders, president of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, said the win "shows what we already know—workers in every part of this country want the freedom to join a union, and when we stand together, we have tremendous power. Even though the deck is stacked against us, momentum is on our side, and we're winning."

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) said: "This is a huge victory not only for UAW workers at Volkswagen, but for every worker in America. The tide is turning. Workers all across the country, even in our most conservative states, are sick and tired of corporate greed and are demanding economic justice."

"I think it's a great push for the entire South, and people will follow suit."

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) called the results "an utterly historic victory for the working class."

"Tennessee is shining bright tonight," she wrote on social media Friday. "We are in a new era. Congratulations to the courageous workers in Chattanooga and the entire UAW. Absolutely heroic. Solidarity IS the strategy—across the South, and all over the country."

More Perfect Union said the victory would "change the auto industry, and the future of American labor," and the campaign organizers themselves are aware of the importance of what they've accomplished.

"We understand that the world's watching us," worker Isaac Meadows, who has been at the plant for one year, told More Perfect Union. "You know there's a labor movement in this country, you know, we're poised to be the first domino of many to fall."

Worker Kelcey Smith, who has also been at the plant for one year, added, "I think it's a great push for the entire South, and people will follow suit."

The next domino to fall could be the Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Alabama, where a UAW election is scheduled from May 13-17. All told, more than 10,000 non-union car makers have signed union cards since the UAW launched its historic organizing drive.

For the Chattanooga workers, meanwhile, their next big fight will be to secure their first union-negotiated contract.

"The real fight begins now," Fain told cheering workers. "The real fight is getting your fair share. The real fight is the fight to get more time with your families. The real fight is the fight for our union contract."

"And I can guarantee you one thing," Fain continued, "this international unionist leadership, this membership all over this nation has your back in this fight."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular