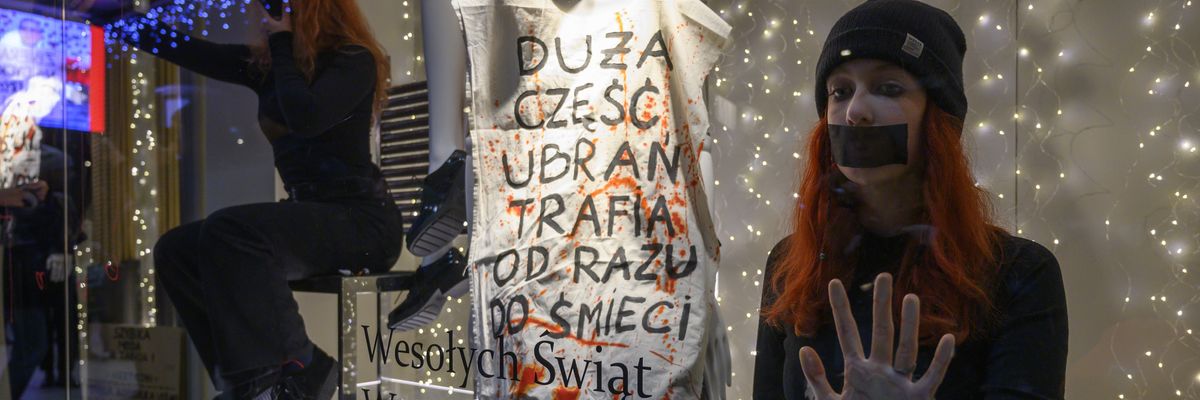

Fast fashion is a poster child of capitalism. Over the past 20 years, fashion production, consumption—and textile waste—have doubled in volume. The current neocolonial status quo is characterized by labor exploitation and cultural appropriation, overproduction, resource depletion, and unprecedented waste generation.

The environmental and social impacts of fashion choices in the Global North are disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations in the Global South. Material throughput of the fashion system should be cut at least in half to stay within the planetary boundaries—but the industry is programmed for growth, mostly in synthetic or plastic garments, on a trajectory to take up to a quarter of the global carbon budget.

Looking good does not have to mean contributing to a broken system.

Our society's addiction to growth fuels this cycle, prioritising profit over all else. While offering consumers the illusion of choice, the current linear fashion business model leads to wardrobe clutter, constant pressure to keep up with trends that causes the feeling of exclusion—and exacerbates further the class divide.

But looking good doesn't have to mean fueling a destructive and exploitative growth model. Moving beyond growth and the mentality that "more stuff is better" could help reshape the fashion system—and make us happier in the long run.

The Beyond Growth Vision

What would it mean to move beyond growth in fashion—in practice?

For Citizens

Addressing the constant push for "more" would be a good start. Why do we seek more stuff? If we zoom into the basic needs behind our overconsumption, we'll find the needs to belong, to be part of a community and respected by our peers, and the needs for self-expression and feeling safe in our environment. But what if there were other ways to fulfil these basic needs instead of buying more stuff?

Buying more consciously—prioritizing quality, longevity, circularity, ethical and local production—is important. But we cannot buy our way out of the crisis of overconsumption by buying "green." The only consumer-citizens' action that can make all the difference is to simply buy less new stuff.

Before we rush to defend our right to shop as if there's no tomorrow, as enshrined in the "constitution" of capitalism, let's take a moment to talk about "less." More isn't always better, and less isn't always worse. Think about war. Production of weapons contributes positively to the growth of GDP—but are weapons a good thing? Could it be possible that too much fashion is not a good thing? And if so, how much fashion is enough? Consider this:

- A Parisian woman in the 1960s had a wardrobe of 40 garments, including shoes and accessories.

- An average Dutch wardrobe today contains 175 garments.

- A wardrobe to stay under the 1.5°C limit of the Paris agreement should contain 80 garments.

- People who voluntarily chose to downsize their wardrobes and only keep garments they love report higher levels of subjective well-being.

It turns out that, not only can we do with less, but living with a curated "less" makes us happier, more conscious about style and more in control of our spending. And—it is also great for the planet. Importantly, moving beyond the "buy more" mentality could help us take back creative control over our self-expression and encourage more diverse personal styles and empower true uniqueness.

Scaling down our irresponsible and wasteful buying habits can have a long-term reinvigorating effect on individuals and on our communities. Instead of buying new things online, alone, to feel better in a crazy world we live in, we could join mending and repair workshops, swaps, upcycling or creative clubs—meet like-minded people, make friends, and become part of a community.

For the Fashion Industry

There is no easy way to replace centuries of growth-oriented business logic overnight. For businesses, moving beyond growth would mean experimentation with ownership structures, new business models and revenue streams to move toward circularity and sufficiency. Profits are not wrong per se, but how they are distributed makes a major difference. The ordeal that Patagonia went through to transform its ownership model to create an environmental fund to replace its shareholder structure indicates that our legal systems are so tailored to growth models that even moving from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism is difficult.

It would also require rethinking the current overproduction strategy. The majority of items today do not sell: An average sell-through rate is 40-80%. Which begs the question: Does this strategy even work in a saturated market? The industry should take a look at how to reduce stock keeping units (SKUs) and focus on developing more products for circularity as opposed to more products overall. Extending responsibility of brands to what happens to their product after the sale, all the way to the end of life, could be the critical mindshift point opening up doors for responsible circular practices that have not existed before. These would include designing for the next use, repair, and re-manufacture.

Citizens are more than just consumers, and we can advocate for change and shift the narrative toward a beautiful fashion future in which less is more.

However, these changes cannot occur in competition with the dominant unsustainable and unethical growth-oriented industry practices. To move beyond growth and let post-growth business experimentation flourish, it is critical to even out the playing field through regulations. Governments could take the first step by banning or restricting business practices that constitute fast and ultra-fast fashion models. A great example is France that sets a tax for companies that put more than 2,000 styles on the market daily.

Another example is

Amsterdam. They city made an effort to go beyond GDP by applying Doughnut Economic Frameworks to align the fashion industry with well-being economy principles, such as reducing waste and promoting sustainable practices. One initiative encourages citizens to mend their clothes through repair cafes, fostering a culture of reuse and reducing the demand for fast fashion.

Other options could be tax incentives for sustainable practices, restrictions on harmful materials, monitoring for transparency, support for circular economies, and education (e.g. learning how to repair your clothes). It is also crucial to regulate planned obsolescence, reinforce the right to repair, as well as implement non-for-profit extended producer responsibility. Side policies could also include banning some advertising, especially that of fast fashion brands, as well as the use of algorithms and tracking consumer data by brands.

Fashion Forward

Looking good does not have to mean contributing to a broken system. Citizens are more than just consumers, and we can advocate for change and shift the narrative toward a beautiful fashion future in which less is more. Choosing to recognize our core needs and find alternatives, as well as finding creative and joyful ways to fill them other than shopping for clothes, is an act of empowerment that can heal us, our planet, and the very system that is very, very sick.