SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

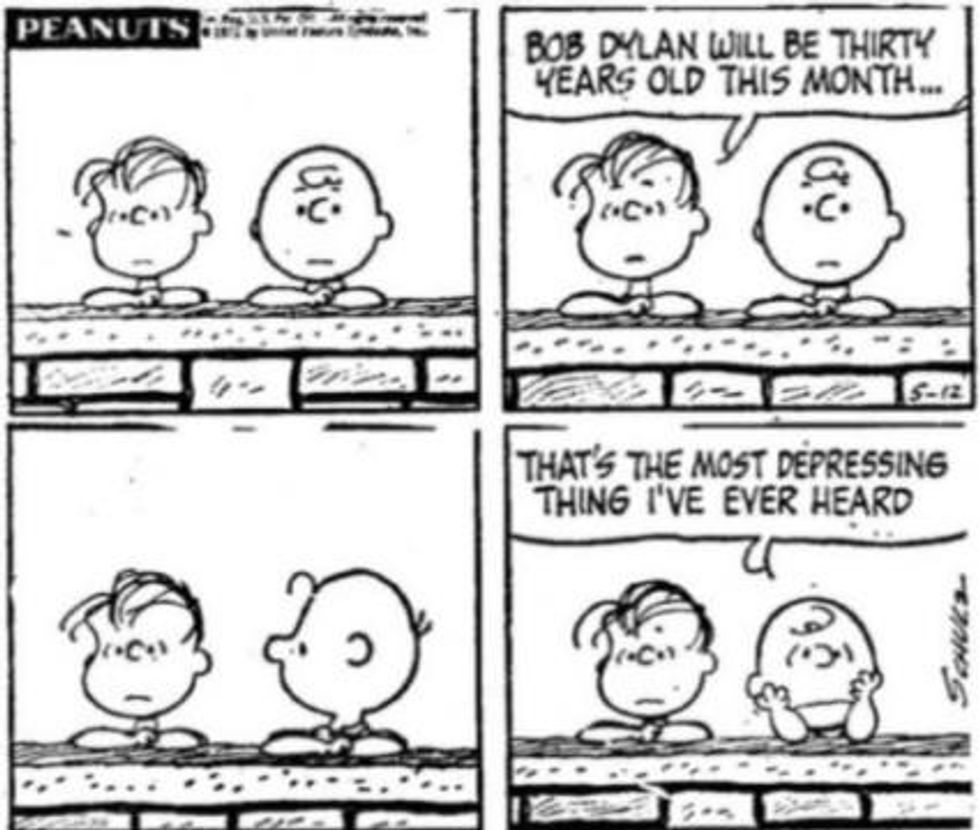

Unreal: Bob Dylan - the master, the muse, the balky, brilliant, prescient "champion of the otherworld" - turns 80 this week. Over 60 years and 600 songs, he's been furiously, tenderly "calling America's bluff," from declaring the times were a-changin' to enduring Desolation Row to last year's Murder Most Foul, "so dense it's overwhelming." "The greatness lies in the body of work," so tributes have poured in. But Bob, as always, remains elusive: "It ain't me you're looking for, babe."

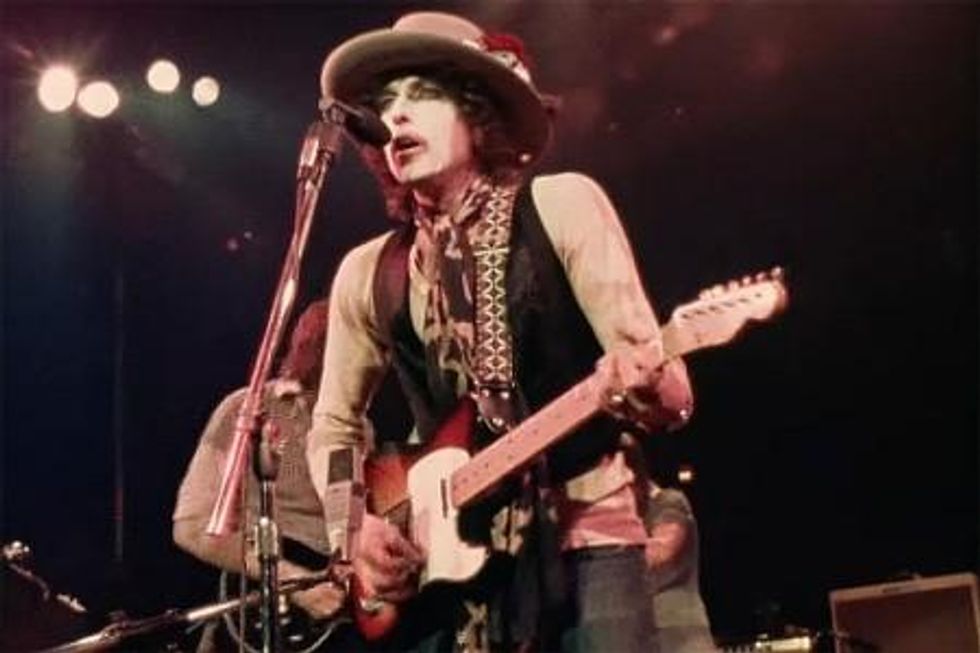

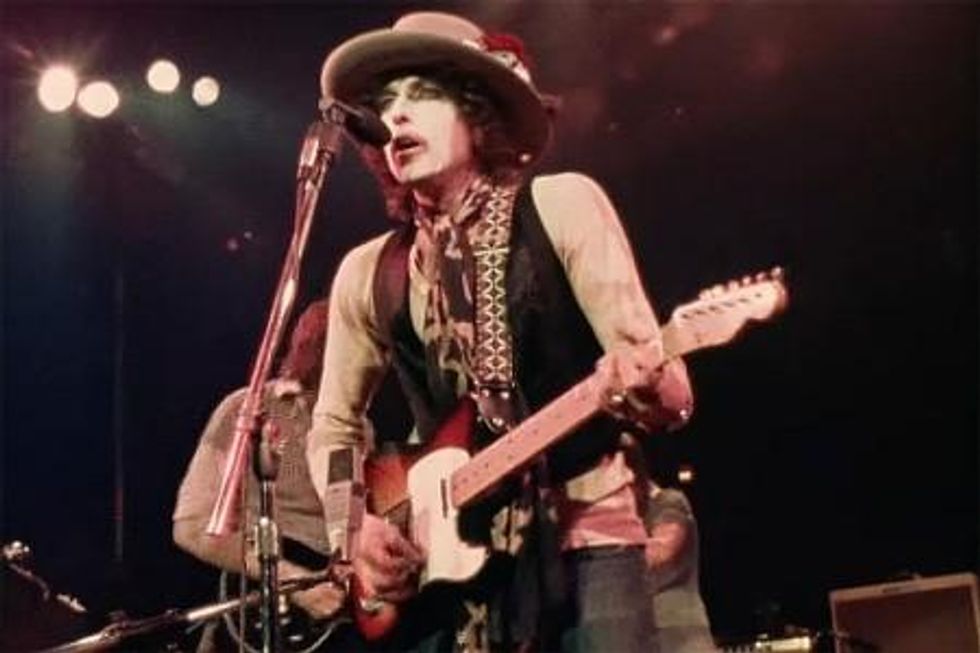

Rolling Thunder, electrifying and unforgettable

It's not dark yet

Waiting to receive Medal of Freedom from Obama

Hard Rain at Rolling Thunder

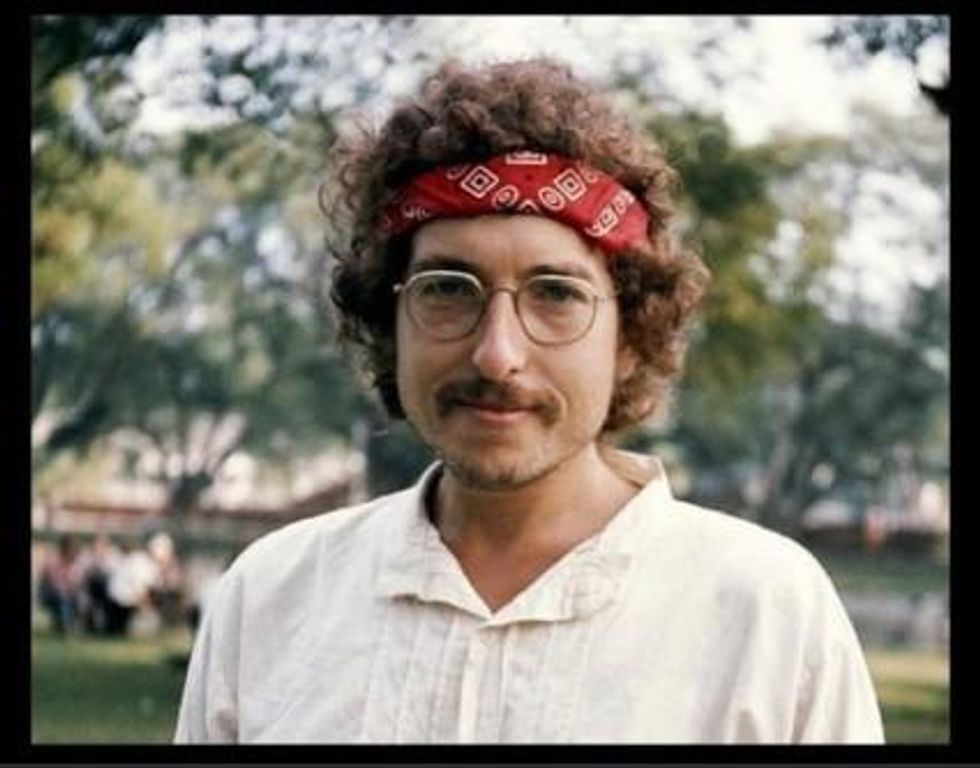

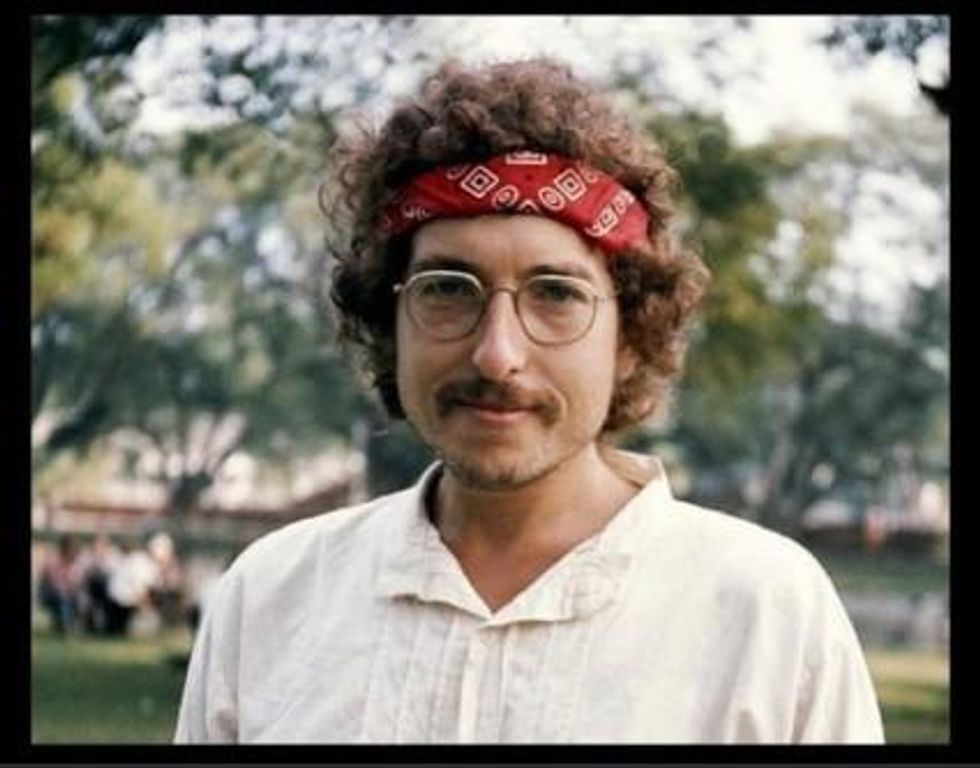

Ah, but I was so much older then/I'm younger than that now

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Rolling Thunder, electrifying and unforgettable

It's not dark yet

Waiting to receive Medal of Freedom from Obama

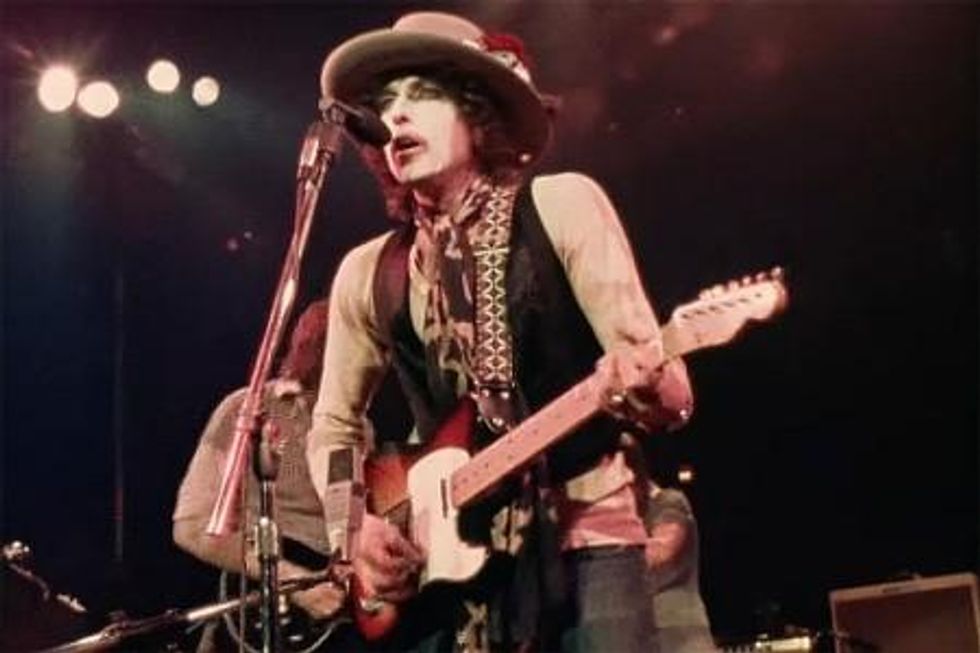

Hard Rain at Rolling Thunder

Ah, but I was so much older then/I'm younger than that now

Rolling Thunder, electrifying and unforgettable

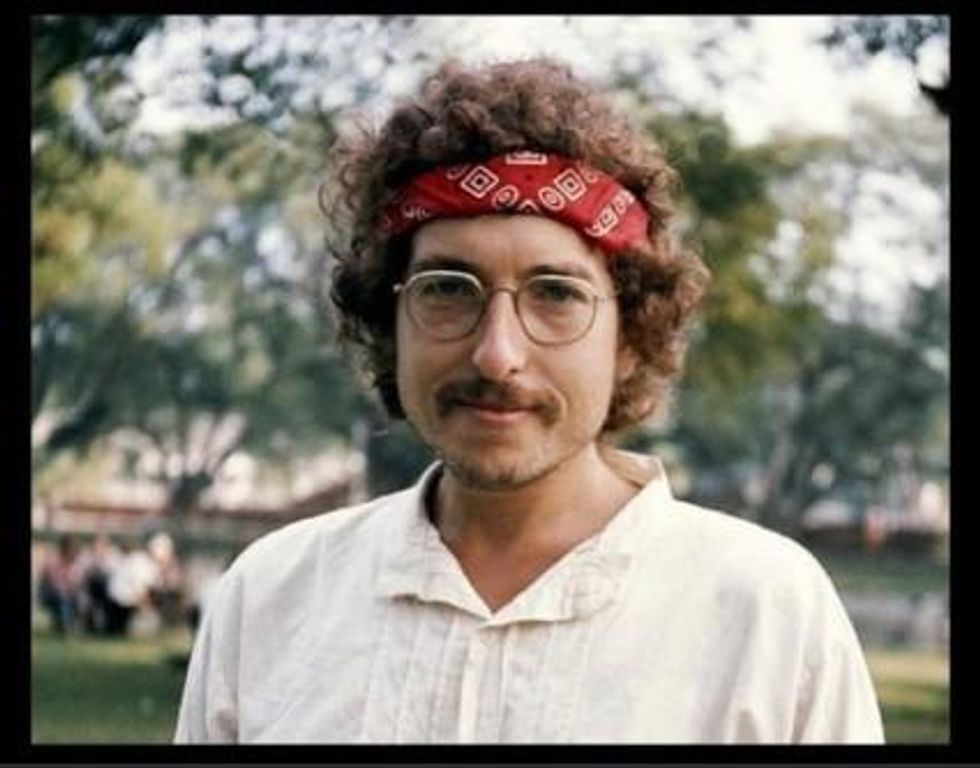

It's not dark yet

Waiting to receive Medal of Freedom from Obama

Hard Rain at Rolling Thunder

Ah, but I was so much older then/I'm younger than that now