SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

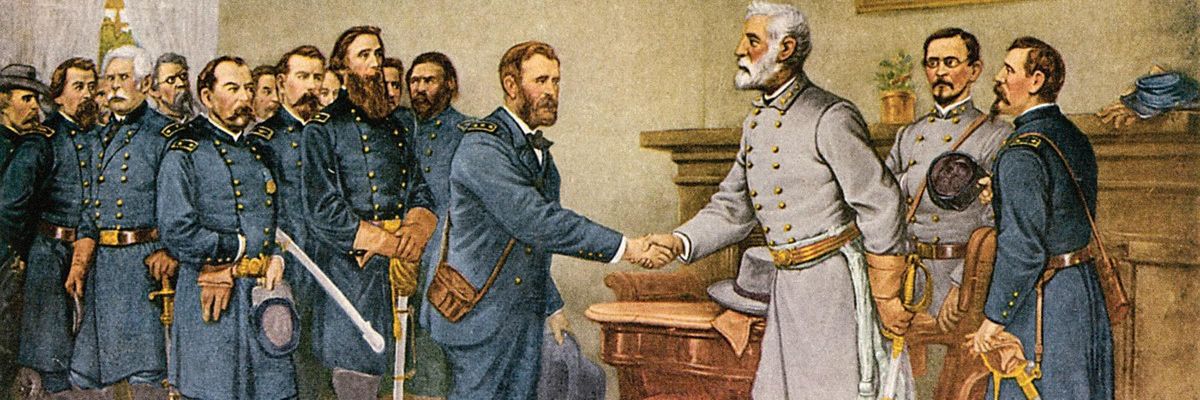

The surrender. One image commemorating the day shows an eagle in honor of the onset of peace with, "Slavery and Treason buried in the same grave!"

This weekend marked the surrender of the Confederate Army under "that genteel butcher Bobby Lee" to Ulysses S. Grant, and the end of the Civil War. After four years and 630,000 lives lost in the sordid name of Southern white supremacy, the date symbolizes an imperfect but hopeful turning point for a nation at bloody war with itself, a nation called on by Abraham Lincoln - himself struck down by hate just days later - to "strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds."

This weekend marked the surrender of the Confederate Army under "that genteel butcher Bobby Lee" to Ulysses S. Grant, and the end of a Civil War that in the sordid name of Southern white supremacy cost four years and 630,000 lives. On Sunday April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army of North Virginia, fighting for the unholy right to own other human beings as property, to General Ulysses S. Grant; the ceremony at the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean in the town of Appomattox Court House, VA took an hour and a half. Days before, Grant had ridden west to ask Lee's cornered band to surrender, declaring any "further effusion of blood" would be solely on Lee's traitorous hands. Lee declined, but did ask about a possible peace agreement; the gentlemanly Grant offered a possible military surrender instead. On that Sunday, writes Heather Cox Richardson, admirably bringing the historic down to human scale, Grant woke with a migraine, having spent the night treating it with mustard plasters that didn't work: "In the morning, Grant pulled on his dirty clothes and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing." Lee, ever the brutal but elegant plantation owner, had dressed grandly in dress uniform, expecting to be taken prisoner; instead, under the surrender's generous terms, his military leaders were spared criminal trials, and handsomely fed. Notes Thomas Levenson, "Looking forward, not back, is no new trope in American politics."

Though the war dragged on for several months, Appomattox marked the inevitable victory of the Union. About 150 miles away, President Abraham Lincoln spent the day steaming up a peaceful Potomac River with a small family party. His guests recalled him sitting in the cabin, reading aloud from Macbeth and stopping to ponder a passage about the slain king Duncan: "After life's fitful fever he sleeps well/Treason has done its worst/...Malice domestic, foreign levey, nothing/Can touch him further." Five days later, Lincoln was killed. Appotomattox was lauded in one image with a noble eagle and the declaration, "Lee has surrendered! Slavery and treason buried in the same grave!" Slavery, yes: Despite the enduring lie by Lost Cause apologists the Confederate fight was about Southern culture and states' rights, they were a slave-holding army fighting to own black people, and they lost that explicit right. As to treason, it still looms: Inexplicably on Page 15 - and below the fold - the once-estimable New York Times reports little Donnie Trump is still at it. But Appotomattox, argues Levenson, "is a great day." Conceding "too much was left undone (and) too much remains undone," the day "enshrined at least the possibility that Federal authority could remedy grievous wrong" - in itself "cause for remembrance of a great hope kindled," and the too-long wait, still ongoing, for its fulfillment. In the tragic end, he quotes the possibly-too-sangine Lincoln, the month before, on the way forward.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right...let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

This weekend marked the surrender of the Confederate Army under "that genteel butcher Bobby Lee" to Ulysses S. Grant, and the end of a Civil War that in the sordid name of Southern white supremacy cost four years and 630,000 lives. On Sunday April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army of North Virginia, fighting for the unholy right to own other human beings as property, to General Ulysses S. Grant; the ceremony at the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean in the town of Appomattox Court House, VA took an hour and a half. Days before, Grant had ridden west to ask Lee's cornered band to surrender, declaring any "further effusion of blood" would be solely on Lee's traitorous hands. Lee declined, but did ask about a possible peace agreement; the gentlemanly Grant offered a possible military surrender instead. On that Sunday, writes Heather Cox Richardson, admirably bringing the historic down to human scale, Grant woke with a migraine, having spent the night treating it with mustard plasters that didn't work: "In the morning, Grant pulled on his dirty clothes and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing." Lee, ever the brutal but elegant plantation owner, had dressed grandly in dress uniform, expecting to be taken prisoner; instead, under the surrender's generous terms, his military leaders were spared criminal trials, and handsomely fed. Notes Thomas Levenson, "Looking forward, not back, is no new trope in American politics."

Though the war dragged on for several months, Appomattox marked the inevitable victory of the Union. About 150 miles away, President Abraham Lincoln spent the day steaming up a peaceful Potomac River with a small family party. His guests recalled him sitting in the cabin, reading aloud from Macbeth and stopping to ponder a passage about the slain king Duncan: "After life's fitful fever he sleeps well/Treason has done its worst/...Malice domestic, foreign levey, nothing/Can touch him further." Five days later, Lincoln was killed. Appotomattox was lauded in one image with a noble eagle and the declaration, "Lee has surrendered! Slavery and treason buried in the same grave!" Slavery, yes: Despite the enduring lie by Lost Cause apologists the Confederate fight was about Southern culture and states' rights, they were a slave-holding army fighting to own black people, and they lost that explicit right. As to treason, it still looms: Inexplicably on Page 15 - and below the fold - the once-estimable New York Times reports little Donnie Trump is still at it. But Appotomattox, argues Levenson, "is a great day." Conceding "too much was left undone (and) too much remains undone," the day "enshrined at least the possibility that Federal authority could remedy grievous wrong" - in itself "cause for remembrance of a great hope kindled," and the too-long wait, still ongoing, for its fulfillment. In the tragic end, he quotes the possibly-too-sangine Lincoln, the month before, on the way forward.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right...let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds."

This weekend marked the surrender of the Confederate Army under "that genteel butcher Bobby Lee" to Ulysses S. Grant, and the end of a Civil War that in the sordid name of Southern white supremacy cost four years and 630,000 lives. On Sunday April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate Army of North Virginia, fighting for the unholy right to own other human beings as property, to General Ulysses S. Grant; the ceremony at the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean in the town of Appomattox Court House, VA took an hour and a half. Days before, Grant had ridden west to ask Lee's cornered band to surrender, declaring any "further effusion of blood" would be solely on Lee's traitorous hands. Lee declined, but did ask about a possible peace agreement; the gentlemanly Grant offered a possible military surrender instead. On that Sunday, writes Heather Cox Richardson, admirably bringing the historic down to human scale, Grant woke with a migraine, having spent the night treating it with mustard plasters that didn't work: "In the morning, Grant pulled on his dirty clothes and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing." Lee, ever the brutal but elegant plantation owner, had dressed grandly in dress uniform, expecting to be taken prisoner; instead, under the surrender's generous terms, his military leaders were spared criminal trials, and handsomely fed. Notes Thomas Levenson, "Looking forward, not back, is no new trope in American politics."

Though the war dragged on for several months, Appomattox marked the inevitable victory of the Union. About 150 miles away, President Abraham Lincoln spent the day steaming up a peaceful Potomac River with a small family party. His guests recalled him sitting in the cabin, reading aloud from Macbeth and stopping to ponder a passage about the slain king Duncan: "After life's fitful fever he sleeps well/Treason has done its worst/...Malice domestic, foreign levey, nothing/Can touch him further." Five days later, Lincoln was killed. Appotomattox was lauded in one image with a noble eagle and the declaration, "Lee has surrendered! Slavery and treason buried in the same grave!" Slavery, yes: Despite the enduring lie by Lost Cause apologists the Confederate fight was about Southern culture and states' rights, they were a slave-holding army fighting to own black people, and they lost that explicit right. As to treason, it still looms: Inexplicably on Page 15 - and below the fold - the once-estimable New York Times reports little Donnie Trump is still at it. But Appotomattox, argues Levenson, "is a great day." Conceding "too much was left undone (and) too much remains undone," the day "enshrined at least the possibility that Federal authority could remedy grievous wrong" - in itself "cause for remembrance of a great hope kindled," and the too-long wait, still ongoing, for its fulfillment. In the tragic end, he quotes the possibly-too-sangine Lincoln, the month before, on the way forward.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right...let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds."