Climate change isn't the only thing affecting the pristine Antarctic ecosystem. Tourists and scientists are inadvertently bringing invasive ("alien") plant seeds with them to the Antarctic, and the plants are likely to spread as the climate warms, a new study says.

The study (pdf), published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), shows that the environment of the Antarctic will likely be degraded by the the establishment of nonindigenous species.

The study states:

Terrestrial Antarctica remains one of the most pristine environments on Earth. However, much concern now exists that the combination of accelerating climate change and the rapidly growing scope and extent of scientific and tourist activities will lead to substantial environmental degradation. One of the primary drivers of this change is thought to be the increasing prospect of the establishment of terrestrial, invasive, nonindigenous species. [...]

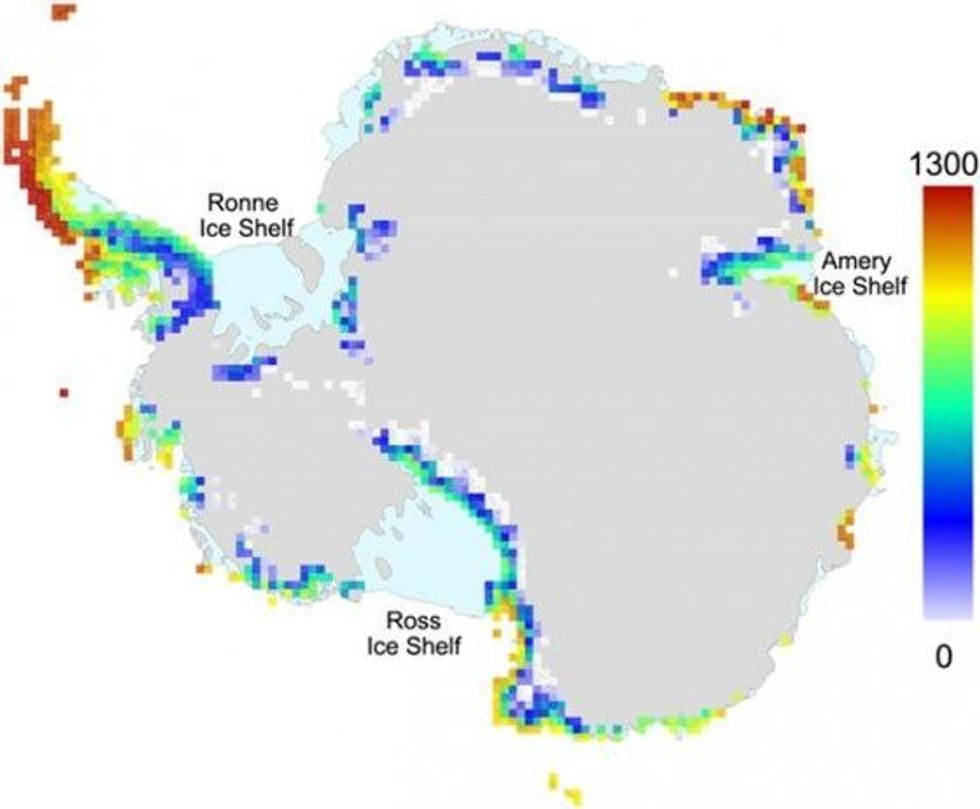

[I]t is clear that several areas of Antarctica are at considerable risk from the establishment of nonindigenous species and that the highest risk sites are those along the Western Antarctic Peninsula.

Nearly half the seeds the scientists collected in their study will in fact be able to survive the Antarctic climate and thus be invasive.

Discovery News adds:

Despite "Don't Pack a Pest" campaigns and plenty of good intentions, tourists and scientists carry thousands of seeds and other detachable plant parts to the southern continent each year in Velcro hems, knit caps and dirty bootlaces.

For the new continent-wide assessment, Steven L. Chown of Stellenbosch University in Matieland, South Africa, and his colleagues sampled, identified, and mapped the sources and destinations of more than 2,600 plant parts that hitched a ride to Antarctica during 2007 and 2008. They found that each visitor transported fewer than 10 seeds on average, but the 30,000-plus Antarctic visitors per year were sufficient for invasive species to establish themselves on the Western Antarctic Peninsula (largest red zone in the map above).

Annual bluegrass is one of the true pioneers among them. This plant has been taking root near research stations for at least 25 years, but last year Polish biologists reported its intrepid spread into non-disturbed areas, some 1.5 kilometers from the nearest research station on the moraines of a retreating glacier on King George Island.

The BBC adds this comment from lead researcher Steven Chown:

If nothing is done, he says, small pockets of the unsullied continent may, in 100 years, look very like sub-Antarctic islands such as South Georgia where alien plants and animals, particularly rats, have dramatically changed the local ecology.

"South Georgia is a great sentinel of what could happen in the area in the next few hundred years," he said.

"My suspicion is that if you didn't take any biosecurity measures you'd end up with a system that would look like a weedy environment with rats, sparrows and Poa annua."