The former CIA officer who ordered the destruction of videotaped interrogations which showed the torture of Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Nashiri in a secret CIA prison in Thailand in 2002, says he did so because he worried about the global repercussions if the footage leaked out and wanted to get "rid of some ugly visuals."

Jose Rodriguez, who oversaw the CIA's once-secret interrogation and detention program, in his new book "Hard Times," writes critically of President Obama's counterterrorism policies and complains openly about the president's public criticism of Bush's torture policies.

"I cannot tell you how disgusted my former colleagues and I felt to hear ourselves labeled 'torturers' by the president of the United States," Rodriguez writes in his book, "Hard Measures," which the Associated Press previewed in a new report.

Complaining about "bureaucratic" hand-wringing in Washington, Rodriguez claims he had the authority to dispose of the tapes. "I wasn't going to sit around another three years waiting for people to get up the courage," to do what CIA lawyers said he had the authority to do himself, Rodriguez writes.

In a story in the Washington Post today, reporter Dana Priest, recalls an episode in 2005 when she was brought to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia to meet with Rodriguez in an attempt by the intelligence agency to convince her not to report on the secret torture program, which was unknown to many at the time.

* * *

Associated Press: Top ex-CIA officer on waterboarding tape destruction: 'Just getting rid of some ugly visuals'

The chapter [in Rodriguez's book] about the interrogation videos adds few new details to a narrative that has been explored for years by journalists, investigators and civil rights groups. But the book represents Rodriguez's first public comment on the matter since the tape destruction was revealed in 2007.

That revelation touched off a political debate and ignited a Justice Department investigation that ultimately produced no charges. Critics accused Rodriguez of covering up torture and preventing the public from ever seeing the brutality of the CIA's interrogations. [...]

The tapes, filmed in a secret CIA prison in Thailand, showed the waterboarding of terrorists Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Nashiri.

Especially after the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal, Rodriguez writes, if the CIA's videos were to leak out, officers worldwide would be in danger.

"I wasn't going to sit around another three years waiting for people to get up the courage," to do what CIA lawyers said he had the authority to do himself, Rodriguez writes. He describes sending the order in November 2005 as "just getting rid of some ugly visuals."

* * *

Washington Post: Former CIA spy boss made an unhesitating call to destroy interrogation tapes

The first and only time I met Jose A. Rodriguez Jr., he was still undercover and in charge of the Central Intelligence Agency's all-powerful operations directorate. The agency had summoned me to its Langley headquarters and his mission was to talk me out of running an article I had just finished reporting about CIA secret prisons -- the "black sites" abroad where the agency put al-Qaeda terrorists so they could be interrogated in isolation, beyond the reach and protections of U.S. law.

The agency had summoned me to its Langley headquarters and his mission was to talk me out of running an article I had just finished reporting about CIA secret prisons -- the "black sites" abroad where the agency put al-Qaeda terrorists so they could be interrogated in isolation, beyond the reach and protections of U.S. law.

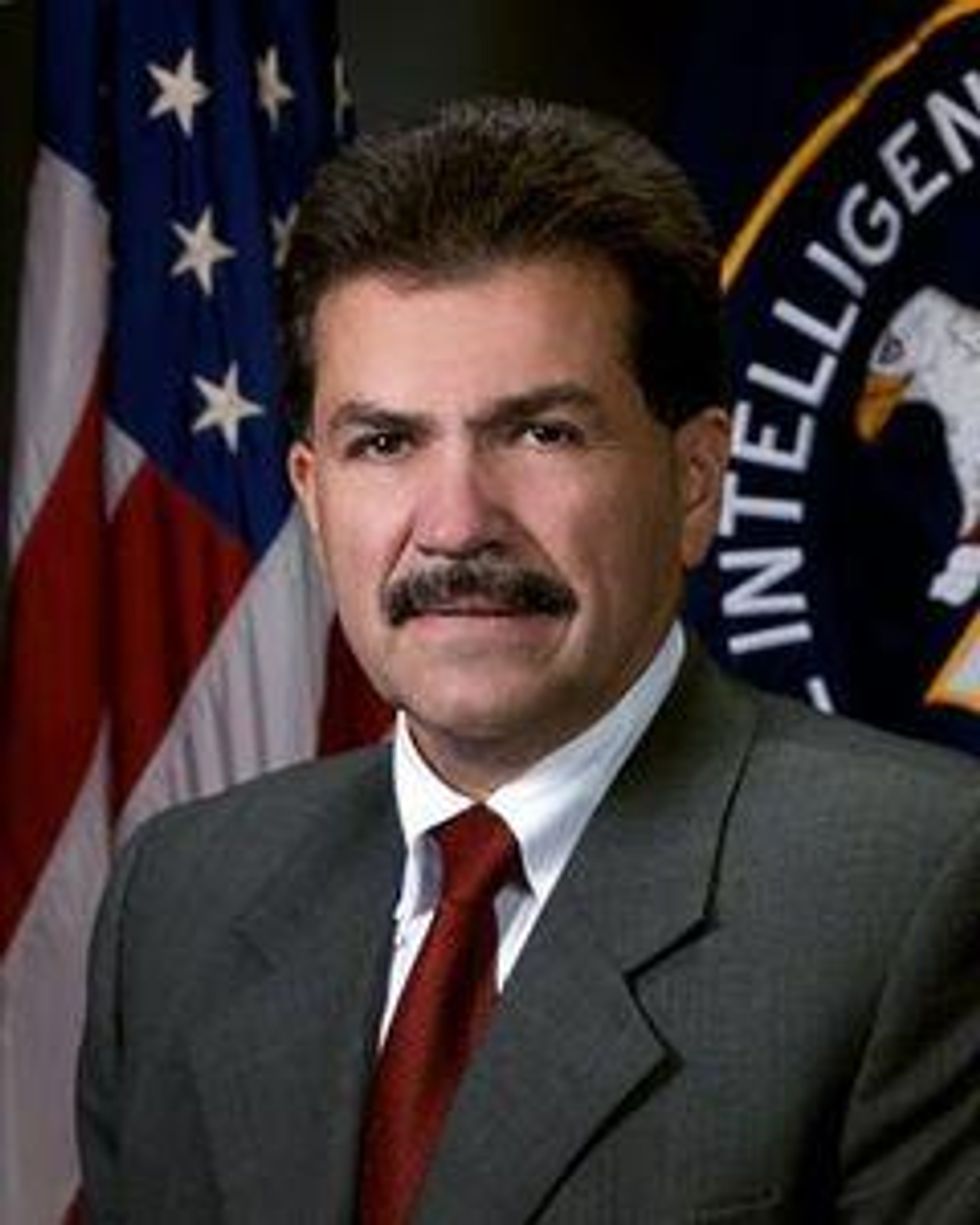

The scene I walked into in November 2005 struck me as incongruous. The man sitting in the middle of the navy blue colonial-style sofa looked like a big-city police detective stuffed uncomfortably into a tailored suit. His face was pockmarked, his dark mustache too big to be stylish. He was not one of the polished career bureaucrats who populate the halls of power in Washington. [...]

What Rodriguez remembers from our conversation, according to his book, is that I brought him a copy of a book I had written about the U.S. military in an effort to butter him up. "That failed to soften my stance on the lack of wisdom of her proceeding with her article as planned," he wrote, and "I could see I was not winning her over." I remember bringing the book because I figured he didn't know one reporter from the next, and I wanted him to know that I did in-depth work and didn't want to just hear the talking points.

A blunt explanation

It became clear immediately that Rodriguez never even got the talking points, which was refreshing and surprising. Right away he began divulging awkward truths that other senior officers had tried to obfuscate in our conversations about the secret prisons: "In many cases they are violating their own laws by helping us," he offered, according to notes I took at the time.

Why not bring the detainees to trial?

"Because they would get lawyered up, and our job, first and foremost, is to obtain information."

(Shortly after our conversation, The Post's senior editors were called to the White House to discuss the article with President George W. Bush and his national security team. Days later, the newspaper published the story, without naming the countries where the prisons were located.)

Rodriguez may have never felt the need to even reveal himself publicly or to write a book, complete with family photos, giving his version of many of the unconventional -- and eventually repudiated -- practices that the CIA engaged in after Sept. 11 had it not been for what happened shortly after our conversation.

Concerned that the location of one of the prisons was about to be revealed, Rodriguez writes that he ordered the facility closed immediately and the detainees moved to a new site. While dismantling the site, the base chief asked Rodriguez if she could throw a pile of old videotapes, made during the early days of terrorist Abu Zubaida's interrogation and waterboarding, and now a couple of years old, onto a nearby bonfire that was set to destroy papers and other evidence of the agency's presence.

Just at that moment, according to his account, a cable from headquarters came in saying: "Hold up on the tapes. We think they should be retained for a little while longer."

"Had that message been delayed by even a few minutes," Rodriguez writes, "my life in the years following would have been considerably easier."

Those actions led to a lengthy and still ongoing investigation of the agency that produced no charges. Rodriguez retired in January 2008 and now works in the private sector. [...]

Shredding the tapes: 'The propaganda damage to the image of America would be immense.'

Rodriguez writes that he ordered the tapes' destruction because he got tired of waiting for his superiors to make a decision. They had at least twice given him the go-ahead, then backed off. In the meantime, a senior agency attorney cited "grave national security reasons" for destroying the material and said the tapes presented '"grave risk" to the personal safety of our officers" whose identities could be seen on the recordings.

"The propaganda damage to the image of America would be immense. But the main concern then, and always, was for the safety of my officers." -Jose Rodriguez

In late April 2004, another event forced his hand, he writes. Photos of the abuse of prisoners by Army soldiers at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq ignited the Arab world and risked being confused with the CIA's program, which was run very differently.

"We knew that if the photos of CIA officers conducting authorized EIT [enhanced interrogation techniques] ever got out, the difference between a legal, authorized, necessary, and safe program and the mindless actions of some MPs [military police] would be buried by the impact of the images.

"The propaganda damage to the image of America would be immense. But the main concern then, and always, was for the safety of my officers." [...]

And after some back-and-forth with agency lawyers for what seemed to him the umpteenth time, he writes, Rodriguez scrutinized a cable to the field drafted by his chief of staff, ordering that the tapes be shredded in an industrial-strength machine. The tapes had already been reviewed, and copious written notes on their content had been taken.

"I was not depriving anyone of information about what was done or what was said," he writes. "I was just getting rid of some ugly visuals that could put the lives of my people at risk.

"I took a deep breath of weary satisfaction and hit Send."

# # #