New research that utilized both ground-based measurements and aerial surveys in specific sub-arctic regions in Alaska and Greenland has discovered approximately 150,000 'methane seeps' - a phenomenon where methane gas previously held in the frozen permafrost beneath tundras or under arctic sea ice, is steadily released when warming causes melting.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas and the sheer amount of it that is naturally existing -- some of it trapped under ground for hundreds or thousands of years -- would dwarf the impact of man-made emission levels if it was released at a rapid rate. This new research, performed by the the new Arctic project, led by Katey Walter Anthony from the University of Alaska at Fairbanks (UAF), and published in the journal Nature Geoscience suggests that the methane stores could have a dramatic and fast-occurring impact on overall global warming and runaway climate change.

"The Arctic is the fastest warming region on the planet, and has many methane sources that will increase as the temperature rises," Prof Euan Nisbet from Royal Holloway, University of London, also involved in Arctic methane research but not with this project, told the BCC in an interview. "This is yet another serious concern: the warming will feed the warming."

* * *

BBC: Arctic melt releasing ancient methane

Using aerial and ground-based surveys, the team identified about 150,000 methane seeps in Alaska and Greenland in lakes along the margins of ice cover.

Local sampling showed that some of these are releasing the ancient methane, perhaps from natural gas or coal deposits underneath the lakes, whereas others are emitting much younger gas, presumably formed through decay of plant material in the lakes.

"We observed most of these cryosphere-cap seeps in lakes along the boundaries of permafrost thaw and in moraines and fjords of retreating glaciers," they write, emphasizing the point that warming in the Arctic is releasing this long-stored carbon.

"If this relationship holds true for other regions where sedimentary basins are at present capped by permafrost, glaciers and ice sheets, such as northern West Siberia, rich in natural gas and partially underlain by thin permafrost predicted to degrade substantially by 2100, a very strong increase in methane carbon cycling will result, with potential implications for climate warming feedbacks."

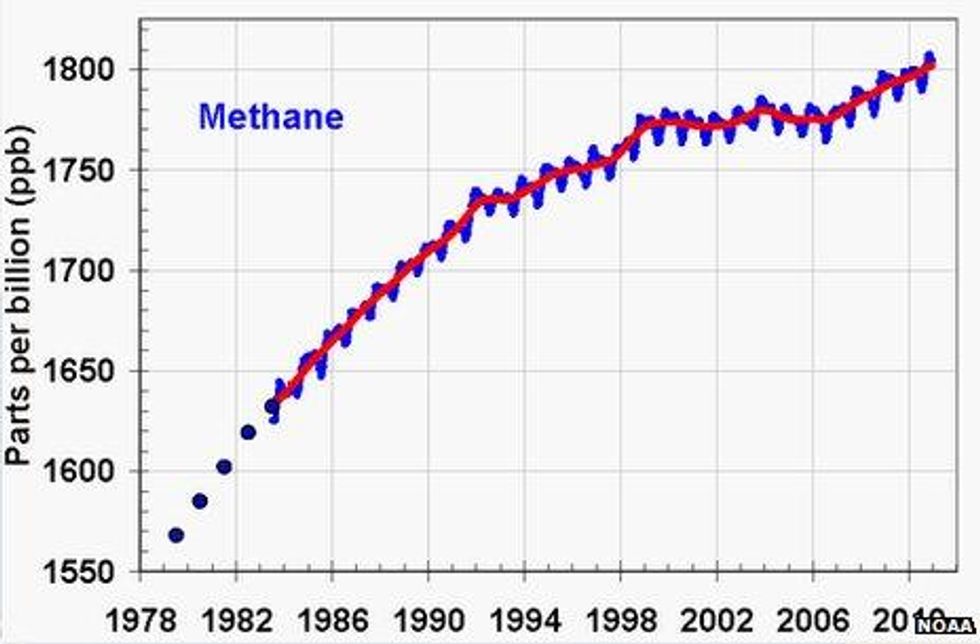

Atmospheric methane concentration is rising again after a plateau of a few years

Atmospheric methane concentration is rising again after a plateau of a few yearsQuantifying methane release across the Arctic is an active area of research, with several countries dispatching missions to monitor sites on land and sea.

The region stores vast quantities of the gas in different places - in and under permafrost on land, on and under the sea bed, and - as evidenced by the latest research - in geological reservoirs.

"The Arctic is the fastest warming region on the planet, and has many methane sources that will increase as the temperature rises," commented Prof Euan Nisbet from Royal Holloway, University of London, who is also involved in Arctic methane research.

"This is yet another serious concern: the warming will feed the warming."

* * *

The Daily Mail: Methane unleashed from 150,000 'seeps' in Alaska and Greenland could have huge impact on world's climate

In an accompanying News and Views article, Giuseppe Etiope writes 'The findings emphasize the potential significance of solid Earth geophysical processes to the atmospheric greenhouse gas budget.'

It's already known that methane is being released into the atmosphere - both from the Siberian permafrost, and, as more recently discovered by survey ships, from the sea bed.

'We found more than 100 fountains, some more than a kilometer across,' said Dr Igor Semiletov, 'These are methane fields on a scale not seen before. The emissions went directly into the atmosphere.'

Earlier research conducted by Semiletov's team had concluded that the amount of methane currently coming out of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is comparable to the amount coming out of the entire world's oceans.

Now Semiletov thinks that could be an underestimate.

The melting of the arctic shelf is melting 'permafrost' under the sea, which is releasing methane stored in the seabed as methane gas.

These releases can be larger and more abrupt than any land-based release. The East Siberian Arctic Shelf is a methane-rich area that encompasses more than 2 million square kilometers of seafloor in the Arctic Ocean.

'Earlier we found torch or fountain-like structures like this,' Semiletov told the Independent. 'This is the first time that we've found continuous, powerful and impressive seeping structures, more than 1,000 meters in diameter. It's amazing.'

'Over a relatively small area, we found more than 100, but over a wider area, there should be thousands of them.'

Semiletov's team used seismic and acoustic monitors to detect methane bubbles rising to the surface.

Scientists estimate that the methane trapped under the ice shelf could lead to extremely rapid climate change.

Current average methane concentrations in the Arctic average about 1.85 parts per million, the highest in 400,000 years. Concentrations above the East Siberian Arctic Shelf are even higher.

The shelf is shallow, 50 meters or less in depth, which means it has been alternately submerged or above water, depending on sea levels throughout Earth's history.

During Earth's coldest periods, it is a frozen arctic coastal plain, and does not release methane.

As the planet warms and sea levels rise, it is inundated with seawater, which is 12-15 degrees warmer than the average air temperature.

In deep water, methane gas oxidizes into carbon dioxide before it reaches the surface. In the shallows of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, methane simply doesn't have enough time to oxidize, which means more of it escapes into the atmosphere.

That, combined with the sheer amount of methane in the region, could add a previously uncalculated variable to climate models.

# # #