Dec 16, 2013

"You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff." -Roger Griggs, pharma exec who now objects to ad campaigns

In the case of medicating a generation of children who were said to be "unusually hyperactive," the answer to that question is addressed by an in-depth investigation by the New York Times on Monday showing that the meteoric rise of diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (A.D.H.D.)--a trend that spawned a pharmaceutical gold rush over the last twenty years--was, in fact, fueled by an industry-led marketing campaign that targeted struggling children, worried parents, and an army of doctors willing to diagnose and prescribe.

And what's worse? The deep-pocketed, pill-pushers are now looking to expand.

As the Times reports:

The rise of A.D.H.D. diagnoses and prescriptions for stimulants over the years coincided with a remarkably successful two-decade campaign by pharmaceutical companies to publicize the syndrome and promote the pills to doctors, educators and parents. With the children's market booming, the industry is now employing similar marketing techniques as it focuses on adult A.D.H.D., which could become even more profitable.

Dr. Keith Conners, a psychologist and professor emeritus at Duke University--who called the rising rates "a national disaster of dangerous proportions"--points out that though A.D.H.D is likely to occur in only 5 percent of the population, recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the diagnosis had been made in 15 percent of high school-age children, and that the number of children on medication for the disorder soared from 600,000 in 1990 to 3.5 million today.

"The numbers make it look like an epidemic. Well, it's not. It's preposterous," he told the Times in an interview. "This is a concoction to justify the giving out of medication at unprecedented and unjustifiable levels."

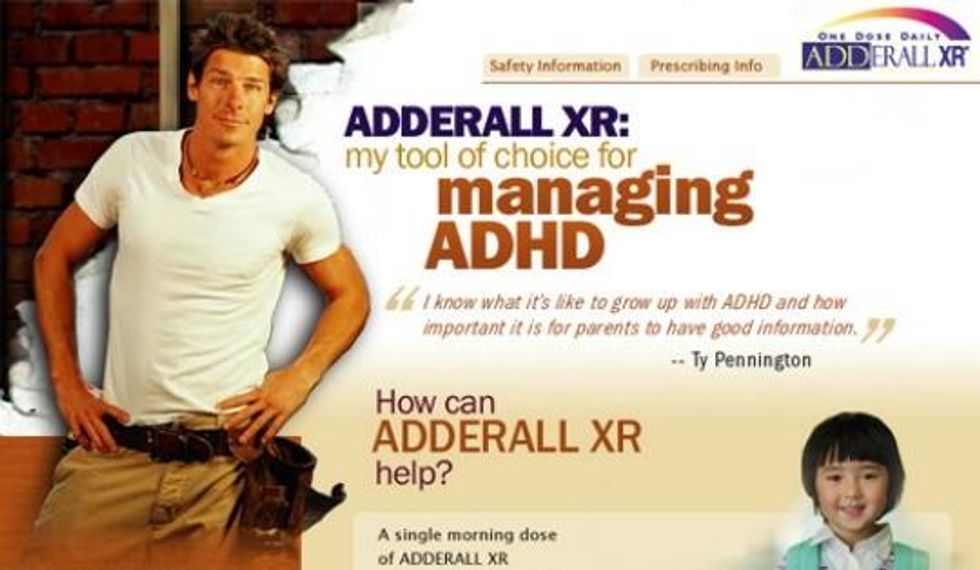

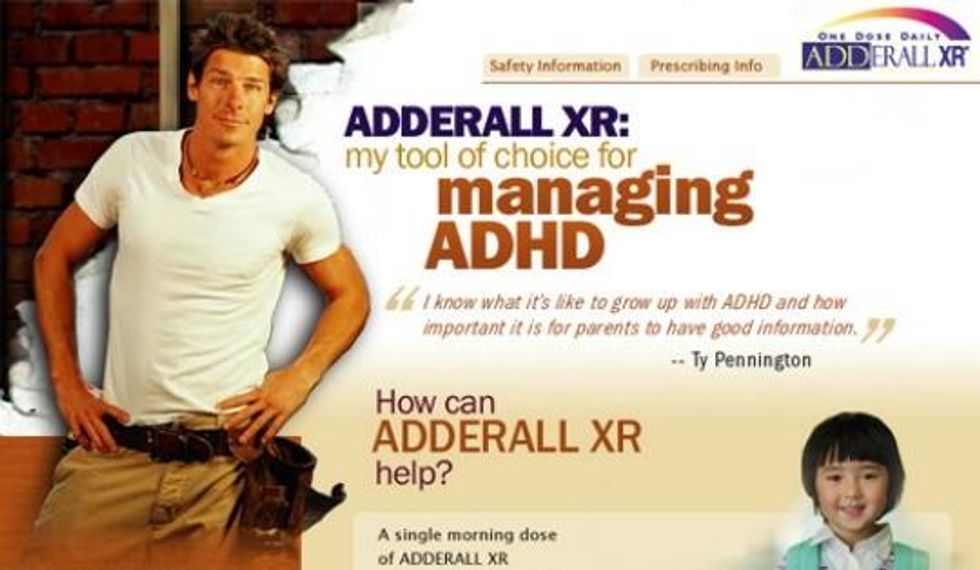

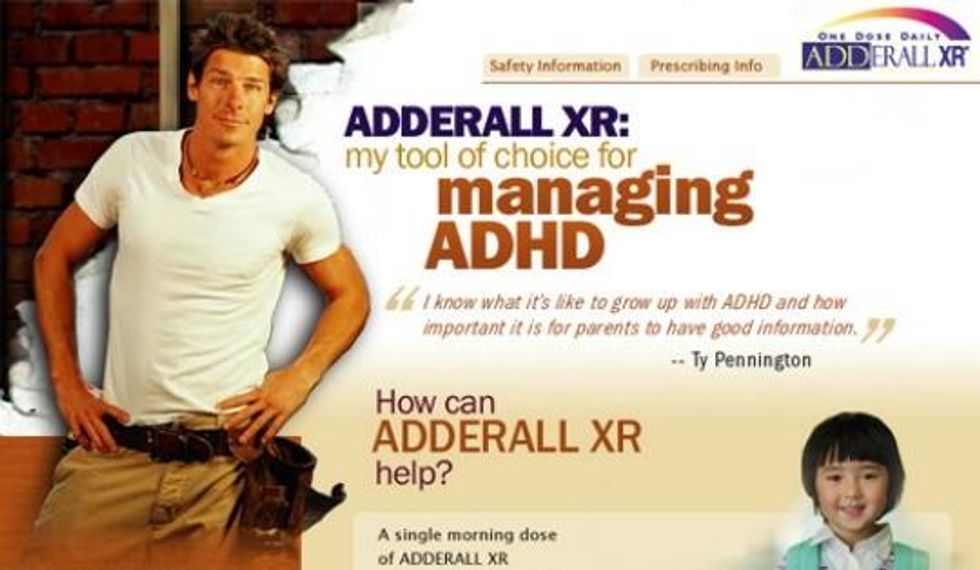

In example after example, the marketing push created by the drug manufacturers show happy children and happy parents citing the wonders of the drugs, which go by their increasingly well-known names--stimulants like Adderall, Concerta, Focalin and Vyvanse, and nonstimulants like Intuniv and Strattera. As the Times reports, every single one of the companies who market these pills has been fined by the FDA for false advertising.

"The decision to start long-term medication should be motivated by observations of patients and physicians, not stimulated by rosy ads." -Kurt Stange, professor of family medicine

But the ads keep coming, it seems, because the ads work.

According to the Times:

Profits for the A.D.H.D. drug industry have soared. Sales of stimulant medication in 2012 were nearly $9 billion, more than five times the $1.7 billion a decade before, according to the data company IMS Health.

Even Roger Griggs, the pharmaceutical executive who introduced Adderall in 1994, said he strongly opposes marketing stimulants to the general public because of their dangers. He calls them "nuclear bombs," warranted only under extreme circumstances and when carefully overseen by a physician.

Psychiatric breakdown and suicidal thoughts are the most rare and extreme results of stimulant addiction, but those horror stories are far outnumbered by people who, seeking to study or work longer hours, cannot sleep for days, lose their appetite or hallucinate. More can simply become habituated to the pills and feel they cannot cope without them.

According to Griggs and others, the idea that drugs like Adderall are being marketed directly to the public is perhaps the key flaw.

"There's no way in God's green earth we would ever promote" a controlled substance like Adderall directly to consumers, Mr. Griggs said as he was shown several advertisements. "You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff."

And Kurt Stange, a professor of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, agrees and recommends that this practice be banned.

In an op-ed published alongside the Times reporting, Stange writes:

Drugs have harms as well as benefits, and the harms are greater when drugs are indiscriminately prescribed. Consumer advertising, delivered to the masses as a shotgun blast, rather than as specific information to concerned patients or caregivers, results in more prescriptions and less appropriate prescribing.

There is no evidence that consumer ads improve treatment quality or result in earlier provision of needed care. Research has shown that the ads convey an unbalanced picture, with benefits and emotional appeals given far greater weight than risks. Clinicians can work to override these miscues, but this steals precious time from activities that can provide real benefit to patients. In the packed agenda of the patient visit, in which so many real concerns and evidence-based care are available to make a difference in people's lives, the intrusion of marketing risks harm.

Advertising also provokes a subtle shift in our culture -- toward seeking a pill for every ill. While there are many for whom stimulants and other medications can be a godsend, the case of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a prime example of how, too often, a pill substitutes for more human responses to distress. U.S. clinicians prescribe stimulant medication for A.D.H.D. at a rate 25 times that of their European counterparts. The complex decision to start a long-term medication should be motivated by the observations of teachers and parents and children, in the context of a relationship with a caring clinician - not stimulated by rosy ads.

_____________________________

Why Your Ongoing Support Is Essential

Donald Trump’s attacks on democracy, justice, and a free press are escalating — putting everything we stand for at risk. We believe a better world is possible, but we can’t get there without your support. Common Dreams stands apart. We answer only to you — our readers, activists, and changemakers — not to billionaires or corporations. Our independence allows us to cover the vital stories that others won’t, spotlighting movements for peace, equality, and human rights. Right now, our work faces unprecedented challenges. Misinformation is spreading, journalists are under attack, and financial pressures are mounting. As a reader-supported, nonprofit newsroom, your support is crucial to keep this journalism alive. Whatever you can give — $10, $25, or $100 — helps us stay strong and responsive when the world needs us most. Together, we’ll continue to build the independent, courageous journalism our movement relies on. Thank you for being part of this community. |

Our work is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0). Feel free to republish and share widely.

"You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff." -Roger Griggs, pharma exec who now objects to ad campaigns

In the case of medicating a generation of children who were said to be "unusually hyperactive," the answer to that question is addressed by an in-depth investigation by the New York Times on Monday showing that the meteoric rise of diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (A.D.H.D.)--a trend that spawned a pharmaceutical gold rush over the last twenty years--was, in fact, fueled by an industry-led marketing campaign that targeted struggling children, worried parents, and an army of doctors willing to diagnose and prescribe.

And what's worse? The deep-pocketed, pill-pushers are now looking to expand.

As the Times reports:

The rise of A.D.H.D. diagnoses and prescriptions for stimulants over the years coincided with a remarkably successful two-decade campaign by pharmaceutical companies to publicize the syndrome and promote the pills to doctors, educators and parents. With the children's market booming, the industry is now employing similar marketing techniques as it focuses on adult A.D.H.D., which could become even more profitable.

Dr. Keith Conners, a psychologist and professor emeritus at Duke University--who called the rising rates "a national disaster of dangerous proportions"--points out that though A.D.H.D is likely to occur in only 5 percent of the population, recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the diagnosis had been made in 15 percent of high school-age children, and that the number of children on medication for the disorder soared from 600,000 in 1990 to 3.5 million today.

"The numbers make it look like an epidemic. Well, it's not. It's preposterous," he told the Times in an interview. "This is a concoction to justify the giving out of medication at unprecedented and unjustifiable levels."

In example after example, the marketing push created by the drug manufacturers show happy children and happy parents citing the wonders of the drugs, which go by their increasingly well-known names--stimulants like Adderall, Concerta, Focalin and Vyvanse, and nonstimulants like Intuniv and Strattera. As the Times reports, every single one of the companies who market these pills has been fined by the FDA for false advertising.

"The decision to start long-term medication should be motivated by observations of patients and physicians, not stimulated by rosy ads." -Kurt Stange, professor of family medicine

But the ads keep coming, it seems, because the ads work.

According to the Times:

Profits for the A.D.H.D. drug industry have soared. Sales of stimulant medication in 2012 were nearly $9 billion, more than five times the $1.7 billion a decade before, according to the data company IMS Health.

Even Roger Griggs, the pharmaceutical executive who introduced Adderall in 1994, said he strongly opposes marketing stimulants to the general public because of their dangers. He calls them "nuclear bombs," warranted only under extreme circumstances and when carefully overseen by a physician.

Psychiatric breakdown and suicidal thoughts are the most rare and extreme results of stimulant addiction, but those horror stories are far outnumbered by people who, seeking to study or work longer hours, cannot sleep for days, lose their appetite or hallucinate. More can simply become habituated to the pills and feel they cannot cope without them.

According to Griggs and others, the idea that drugs like Adderall are being marketed directly to the public is perhaps the key flaw.

"There's no way in God's green earth we would ever promote" a controlled substance like Adderall directly to consumers, Mr. Griggs said as he was shown several advertisements. "You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff."

And Kurt Stange, a professor of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, agrees and recommends that this practice be banned.

In an op-ed published alongside the Times reporting, Stange writes:

Drugs have harms as well as benefits, and the harms are greater when drugs are indiscriminately prescribed. Consumer advertising, delivered to the masses as a shotgun blast, rather than as specific information to concerned patients or caregivers, results in more prescriptions and less appropriate prescribing.

There is no evidence that consumer ads improve treatment quality or result in earlier provision of needed care. Research has shown that the ads convey an unbalanced picture, with benefits and emotional appeals given far greater weight than risks. Clinicians can work to override these miscues, but this steals precious time from activities that can provide real benefit to patients. In the packed agenda of the patient visit, in which so many real concerns and evidence-based care are available to make a difference in people's lives, the intrusion of marketing risks harm.

Advertising also provokes a subtle shift in our culture -- toward seeking a pill for every ill. While there are many for whom stimulants and other medications can be a godsend, the case of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a prime example of how, too often, a pill substitutes for more human responses to distress. U.S. clinicians prescribe stimulant medication for A.D.H.D. at a rate 25 times that of their European counterparts. The complex decision to start a long-term medication should be motivated by the observations of teachers and parents and children, in the context of a relationship with a caring clinician - not stimulated by rosy ads.

_____________________________

"You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff." -Roger Griggs, pharma exec who now objects to ad campaigns

In the case of medicating a generation of children who were said to be "unusually hyperactive," the answer to that question is addressed by an in-depth investigation by the New York Times on Monday showing that the meteoric rise of diagnoses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (A.D.H.D.)--a trend that spawned a pharmaceutical gold rush over the last twenty years--was, in fact, fueled by an industry-led marketing campaign that targeted struggling children, worried parents, and an army of doctors willing to diagnose and prescribe.

And what's worse? The deep-pocketed, pill-pushers are now looking to expand.

As the Times reports:

The rise of A.D.H.D. diagnoses and prescriptions for stimulants over the years coincided with a remarkably successful two-decade campaign by pharmaceutical companies to publicize the syndrome and promote the pills to doctors, educators and parents. With the children's market booming, the industry is now employing similar marketing techniques as it focuses on adult A.D.H.D., which could become even more profitable.

Dr. Keith Conners, a psychologist and professor emeritus at Duke University--who called the rising rates "a national disaster of dangerous proportions"--points out that though A.D.H.D is likely to occur in only 5 percent of the population, recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the diagnosis had been made in 15 percent of high school-age children, and that the number of children on medication for the disorder soared from 600,000 in 1990 to 3.5 million today.

"The numbers make it look like an epidemic. Well, it's not. It's preposterous," he told the Times in an interview. "This is a concoction to justify the giving out of medication at unprecedented and unjustifiable levels."

In example after example, the marketing push created by the drug manufacturers show happy children and happy parents citing the wonders of the drugs, which go by their increasingly well-known names--stimulants like Adderall, Concerta, Focalin and Vyvanse, and nonstimulants like Intuniv and Strattera. As the Times reports, every single one of the companies who market these pills has been fined by the FDA for false advertising.

"The decision to start long-term medication should be motivated by observations of patients and physicians, not stimulated by rosy ads." -Kurt Stange, professor of family medicine

But the ads keep coming, it seems, because the ads work.

According to the Times:

Profits for the A.D.H.D. drug industry have soared. Sales of stimulant medication in 2012 were nearly $9 billion, more than five times the $1.7 billion a decade before, according to the data company IMS Health.

Even Roger Griggs, the pharmaceutical executive who introduced Adderall in 1994, said he strongly opposes marketing stimulants to the general public because of their dangers. He calls them "nuclear bombs," warranted only under extreme circumstances and when carefully overseen by a physician.

Psychiatric breakdown and suicidal thoughts are the most rare and extreme results of stimulant addiction, but those horror stories are far outnumbered by people who, seeking to study or work longer hours, cannot sleep for days, lose their appetite or hallucinate. More can simply become habituated to the pills and feel they cannot cope without them.

According to Griggs and others, the idea that drugs like Adderall are being marketed directly to the public is perhaps the key flaw.

"There's no way in God's green earth we would ever promote" a controlled substance like Adderall directly to consumers, Mr. Griggs said as he was shown several advertisements. "You're talking about a product that's having a major impact on brain chemistry. Parents are very susceptible to this type of stuff."

And Kurt Stange, a professor of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, agrees and recommends that this practice be banned.

In an op-ed published alongside the Times reporting, Stange writes:

Drugs have harms as well as benefits, and the harms are greater when drugs are indiscriminately prescribed. Consumer advertising, delivered to the masses as a shotgun blast, rather than as specific information to concerned patients or caregivers, results in more prescriptions and less appropriate prescribing.

There is no evidence that consumer ads improve treatment quality or result in earlier provision of needed care. Research has shown that the ads convey an unbalanced picture, with benefits and emotional appeals given far greater weight than risks. Clinicians can work to override these miscues, but this steals precious time from activities that can provide real benefit to patients. In the packed agenda of the patient visit, in which so many real concerns and evidence-based care are available to make a difference in people's lives, the intrusion of marketing risks harm.

Advertising also provokes a subtle shift in our culture -- toward seeking a pill for every ill. While there are many for whom stimulants and other medications can be a godsend, the case of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a prime example of how, too often, a pill substitutes for more human responses to distress. U.S. clinicians prescribe stimulant medication for A.D.H.D. at a rate 25 times that of their European counterparts. The complex decision to start a long-term medication should be motivated by the observations of teachers and parents and children, in the context of a relationship with a caring clinician - not stimulated by rosy ads.

_____________________________

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.