SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

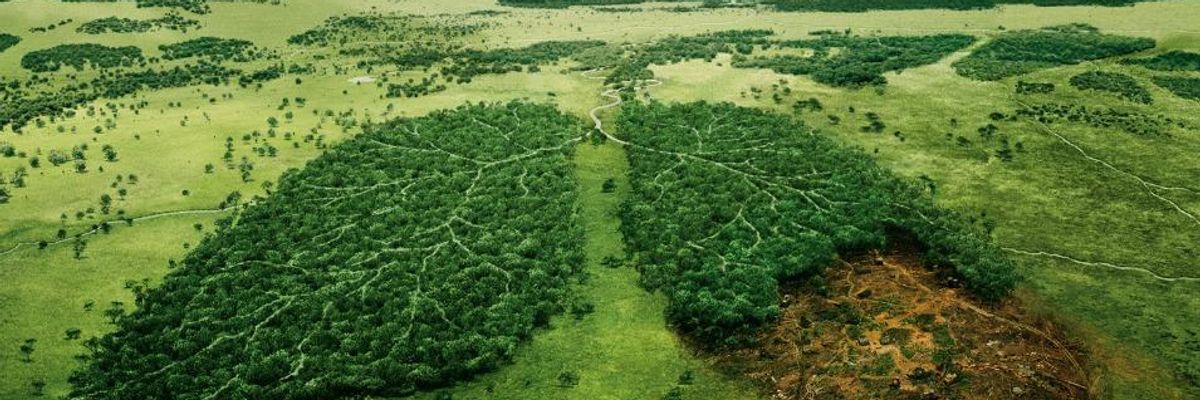

(Image: flickr / cc / World Wildlife Federation/ TBWA\PARI / Nicolas Roncerel)

WASHINGTON - The international community is failing to take advantage of a potent opportunity to counter climate change by strengthening local land tenure rights and laws worldwide, new data suggests.

In what researchers say is the most detailed study on the issue to date, new analysis suggests that in areas formally overseen by local communities, deforestation rates are dozens to hundreds of times lower than in areas overseen by governments or private entities. Anywhere from 10 to 20 percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to deforestation each year.

The findings were released Thursday by the World Resources Institute, a think tank here, and the Rights and Resources Initiative, a global network that focuses on forest tenure.

"This approach to mitigating climate change has long been undervalued," a report detailing the analysis states. "[G]overnments, donors, and other climate change stakeholders tend to ignore or marginalize the enormous contribution to mitigating climate change that expanding and strengthening communities' forest rights can make."

Researchers were able to comb through high-definition satellite imagery and correlate findings on deforestation rates with data on differing tenure approaches in 14 developing countries considered heavily forested. Those areas with significant forest rights vested in local communities were found to be far more successful at slowing forest clearing, including the incursion of settlers and mining companies.

In Guatemala and Brazil, strong local tenure resulted in deforestation rates 11 to 20 times lower than outside of formally recognised community forests. In parts of the Mexican Yucatan the findings were even starker - 350 times lower.

Meanwhile, the climate implications of these forests are significant. Standing, mature forests not only hold massive amounts of carbon, but they also continually suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

"We know that at least 500 million hectares of forest in developing countries are already in the hands of local communities, translating to a bit less than 40 billion tonnes of carbon," Andy White, the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)'s coordinator, told IPS.

"That's a huge amount - 30 times the amount of total emissions from all passenger vehicles around the world. But much of the rights to protect those forests are weak, so there's a real risk that we could lose those forests and that carbon."

White notes that there's been a "massive slowdown" in the recognition of indigenous and other community rights over the past half-decade, despite earlier global headway on the issue. But he now sees significant potential to link land rights with momentum on climate change in the minds of policymakers and the donor community.

"In developing country forests, you have this history of governments promoting deforestation for agriculture but also opening up forests through roads and the promotion of colonisation and mining," White says.

"At the same time, these same governments are now trying to talk about climate change, saying they're concerned about reducing emission. To date, these two hands haven't been talking to each other."

Lima link

The new findings come just ahead of two major global climate summits. In September, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon will host international leaders in New York to discuss the issue, and in December the next round of global climate negotiations will take place in Peru, ahead of intended agreement next year.

The Lima talks are being referred to as the "forest" round. Some observers have suggested that forestry could offer the most significant potential for global emissions cuts, but few have directly connected this potential with local tenure.

"The international community hasn't taken this link nearly as far as it can go, and it's important that policymakers are made aware of this connection," Caleb Stevens, a proper rights specialist at the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the new report's principle author, told IPS.

"Developed country governments can commit to development assistance agencies to strengthen forest tenure as part of bilateral agreements. They can also commit to strengthen these rights through finance mechanisms like the new Green Climate Fund."

Currently the most well-known, if contentious, international mechanism aimed at reducing deforestation is the U.N.'s REDD+ initiative, which since 2008 has dispersed nearly 200 million dollars to safeguard forest in developing countries. Yet critics say the programme has never fully embraced the potential of community forest management.

"REDD+ was established because it is well known that deforestation is a significant part of the climate change problem," Tony LaVina, the lead forest and climate negotiator for the Philippines, said in a statement.

"What is not as widely understood is how effective forest communities are at protecting their forest from deforestation and increasing forest health. This is why REDD+ must be accompanied by community safeguards."

Two-thirds remaining

Meanwhile, WRI's Stevens says that current national-level prioritisation of local tenure is a "mixed bag", varying significantly from country to country.

He points to progressive progress being made in Liberia and Kenya, where laws have started to be reformed to recognise community rights, as well as in Bolivia and Nepal, where some 40 percent of forests are legally under community control. Following a 2013 court ruling, Indonesia could now be on a similar path.

"Many governments are still quite reluctant to stop their attempts access minerals and other resources," Stevens says. "But some governments realise the limitations of their capacity - that this model of government-owned and -managed forests usually doesn't work. Instead, it often creates an open-access free-for-all."

Not only are local communities often more effective at managing such resources than governments or private entities, but they can also become significant economic beneficiaries of those forests, eventually even contributing to national coffers through tax revenues.

Certainly there is scope for such an expansion. RRI estimates that the 500 million hectares currently under community control constitute just a third of what communities around the world are actively - and, the group says, legitimately - claiming.

"The world should rapidly scale up recognition of local forest rights even if they only care about the climate - even if they don't care about the people, about water, women, biodiversity," RRI's White says.

"Actually, of course, people do care about all of these other issues. That's why a strategy of strengthening local forest rights is so important and a no-brainer - it will deliver for the climate as well as reduce poverty."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

WASHINGTON - The international community is failing to take advantage of a potent opportunity to counter climate change by strengthening local land tenure rights and laws worldwide, new data suggests.

In what researchers say is the most detailed study on the issue to date, new analysis suggests that in areas formally overseen by local communities, deforestation rates are dozens to hundreds of times lower than in areas overseen by governments or private entities. Anywhere from 10 to 20 percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to deforestation each year.

The findings were released Thursday by the World Resources Institute, a think tank here, and the Rights and Resources Initiative, a global network that focuses on forest tenure.

"This approach to mitigating climate change has long been undervalued," a report detailing the analysis states. "[G]overnments, donors, and other climate change stakeholders tend to ignore or marginalize the enormous contribution to mitigating climate change that expanding and strengthening communities' forest rights can make."

Researchers were able to comb through high-definition satellite imagery and correlate findings on deforestation rates with data on differing tenure approaches in 14 developing countries considered heavily forested. Those areas with significant forest rights vested in local communities were found to be far more successful at slowing forest clearing, including the incursion of settlers and mining companies.

In Guatemala and Brazil, strong local tenure resulted in deforestation rates 11 to 20 times lower than outside of formally recognised community forests. In parts of the Mexican Yucatan the findings were even starker - 350 times lower.

Meanwhile, the climate implications of these forests are significant. Standing, mature forests not only hold massive amounts of carbon, but they also continually suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

"We know that at least 500 million hectares of forest in developing countries are already in the hands of local communities, translating to a bit less than 40 billion tonnes of carbon," Andy White, the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)'s coordinator, told IPS.

"That's a huge amount - 30 times the amount of total emissions from all passenger vehicles around the world. But much of the rights to protect those forests are weak, so there's a real risk that we could lose those forests and that carbon."

White notes that there's been a "massive slowdown" in the recognition of indigenous and other community rights over the past half-decade, despite earlier global headway on the issue. But he now sees significant potential to link land rights with momentum on climate change in the minds of policymakers and the donor community.

"In developing country forests, you have this history of governments promoting deforestation for agriculture but also opening up forests through roads and the promotion of colonisation and mining," White says.

"At the same time, these same governments are now trying to talk about climate change, saying they're concerned about reducing emission. To date, these two hands haven't been talking to each other."

Lima link

The new findings come just ahead of two major global climate summits. In September, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon will host international leaders in New York to discuss the issue, and in December the next round of global climate negotiations will take place in Peru, ahead of intended agreement next year.

The Lima talks are being referred to as the "forest" round. Some observers have suggested that forestry could offer the most significant potential for global emissions cuts, but few have directly connected this potential with local tenure.

"The international community hasn't taken this link nearly as far as it can go, and it's important that policymakers are made aware of this connection," Caleb Stevens, a proper rights specialist at the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the new report's principle author, told IPS.

"Developed country governments can commit to development assistance agencies to strengthen forest tenure as part of bilateral agreements. They can also commit to strengthen these rights through finance mechanisms like the new Green Climate Fund."

Currently the most well-known, if contentious, international mechanism aimed at reducing deforestation is the U.N.'s REDD+ initiative, which since 2008 has dispersed nearly 200 million dollars to safeguard forest in developing countries. Yet critics say the programme has never fully embraced the potential of community forest management.

"REDD+ was established because it is well known that deforestation is a significant part of the climate change problem," Tony LaVina, the lead forest and climate negotiator for the Philippines, said in a statement.

"What is not as widely understood is how effective forest communities are at protecting their forest from deforestation and increasing forest health. This is why REDD+ must be accompanied by community safeguards."

Two-thirds remaining

Meanwhile, WRI's Stevens says that current national-level prioritisation of local tenure is a "mixed bag", varying significantly from country to country.

He points to progressive progress being made in Liberia and Kenya, where laws have started to be reformed to recognise community rights, as well as in Bolivia and Nepal, where some 40 percent of forests are legally under community control. Following a 2013 court ruling, Indonesia could now be on a similar path.

"Many governments are still quite reluctant to stop their attempts access minerals and other resources," Stevens says. "But some governments realise the limitations of their capacity - that this model of government-owned and -managed forests usually doesn't work. Instead, it often creates an open-access free-for-all."

Not only are local communities often more effective at managing such resources than governments or private entities, but they can also become significant economic beneficiaries of those forests, eventually even contributing to national coffers through tax revenues.

Certainly there is scope for such an expansion. RRI estimates that the 500 million hectares currently under community control constitute just a third of what communities around the world are actively - and, the group says, legitimately - claiming.

"The world should rapidly scale up recognition of local forest rights even if they only care about the climate - even if they don't care about the people, about water, women, biodiversity," RRI's White says.

"Actually, of course, people do care about all of these other issues. That's why a strategy of strengthening local forest rights is so important and a no-brainer - it will deliver for the climate as well as reduce poverty."

WASHINGTON - The international community is failing to take advantage of a potent opportunity to counter climate change by strengthening local land tenure rights and laws worldwide, new data suggests.

In what researchers say is the most detailed study on the issue to date, new analysis suggests that in areas formally overseen by local communities, deforestation rates are dozens to hundreds of times lower than in areas overseen by governments or private entities. Anywhere from 10 to 20 percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to deforestation each year.

The findings were released Thursday by the World Resources Institute, a think tank here, and the Rights and Resources Initiative, a global network that focuses on forest tenure.

"This approach to mitigating climate change has long been undervalued," a report detailing the analysis states. "[G]overnments, donors, and other climate change stakeholders tend to ignore or marginalize the enormous contribution to mitigating climate change that expanding and strengthening communities' forest rights can make."

Researchers were able to comb through high-definition satellite imagery and correlate findings on deforestation rates with data on differing tenure approaches in 14 developing countries considered heavily forested. Those areas with significant forest rights vested in local communities were found to be far more successful at slowing forest clearing, including the incursion of settlers and mining companies.

In Guatemala and Brazil, strong local tenure resulted in deforestation rates 11 to 20 times lower than outside of formally recognised community forests. In parts of the Mexican Yucatan the findings were even starker - 350 times lower.

Meanwhile, the climate implications of these forests are significant. Standing, mature forests not only hold massive amounts of carbon, but they also continually suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

"We know that at least 500 million hectares of forest in developing countries are already in the hands of local communities, translating to a bit less than 40 billion tonnes of carbon," Andy White, the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI)'s coordinator, told IPS.

"That's a huge amount - 30 times the amount of total emissions from all passenger vehicles around the world. But much of the rights to protect those forests are weak, so there's a real risk that we could lose those forests and that carbon."

White notes that there's been a "massive slowdown" in the recognition of indigenous and other community rights over the past half-decade, despite earlier global headway on the issue. But he now sees significant potential to link land rights with momentum on climate change in the minds of policymakers and the donor community.

"In developing country forests, you have this history of governments promoting deforestation for agriculture but also opening up forests through roads and the promotion of colonisation and mining," White says.

"At the same time, these same governments are now trying to talk about climate change, saying they're concerned about reducing emission. To date, these two hands haven't been talking to each other."

Lima link

The new findings come just ahead of two major global climate summits. In September, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon will host international leaders in New York to discuss the issue, and in December the next round of global climate negotiations will take place in Peru, ahead of intended agreement next year.

The Lima talks are being referred to as the "forest" round. Some observers have suggested that forestry could offer the most significant potential for global emissions cuts, but few have directly connected this potential with local tenure.

"The international community hasn't taken this link nearly as far as it can go, and it's important that policymakers are made aware of this connection," Caleb Stevens, a proper rights specialist at the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the new report's principle author, told IPS.

"Developed country governments can commit to development assistance agencies to strengthen forest tenure as part of bilateral agreements. They can also commit to strengthen these rights through finance mechanisms like the new Green Climate Fund."

Currently the most well-known, if contentious, international mechanism aimed at reducing deforestation is the U.N.'s REDD+ initiative, which since 2008 has dispersed nearly 200 million dollars to safeguard forest in developing countries. Yet critics say the programme has never fully embraced the potential of community forest management.

"REDD+ was established because it is well known that deforestation is a significant part of the climate change problem," Tony LaVina, the lead forest and climate negotiator for the Philippines, said in a statement.

"What is not as widely understood is how effective forest communities are at protecting their forest from deforestation and increasing forest health. This is why REDD+ must be accompanied by community safeguards."

Two-thirds remaining

Meanwhile, WRI's Stevens says that current national-level prioritisation of local tenure is a "mixed bag", varying significantly from country to country.

He points to progressive progress being made in Liberia and Kenya, where laws have started to be reformed to recognise community rights, as well as in Bolivia and Nepal, where some 40 percent of forests are legally under community control. Following a 2013 court ruling, Indonesia could now be on a similar path.

"Many governments are still quite reluctant to stop their attempts access minerals and other resources," Stevens says. "But some governments realise the limitations of their capacity - that this model of government-owned and -managed forests usually doesn't work. Instead, it often creates an open-access free-for-all."

Not only are local communities often more effective at managing such resources than governments or private entities, but they can also become significant economic beneficiaries of those forests, eventually even contributing to national coffers through tax revenues.

Certainly there is scope for such an expansion. RRI estimates that the 500 million hectares currently under community control constitute just a third of what communities around the world are actively - and, the group says, legitimately - claiming.

"The world should rapidly scale up recognition of local forest rights even if they only care about the climate - even if they don't care about the people, about water, women, biodiversity," RRI's White says.

"Actually, of course, people do care about all of these other issues. That's why a strategy of strengthening local forest rights is so important and a no-brainer - it will deliver for the climate as well as reduce poverty."