SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

A woman wails near the location of a mass grave in the village of Peraliya in southern Sri Lanka. Thousands continue to struggle with trauma and depression, ten years after the disaster. (Photo: Amantha Perera/IPS)

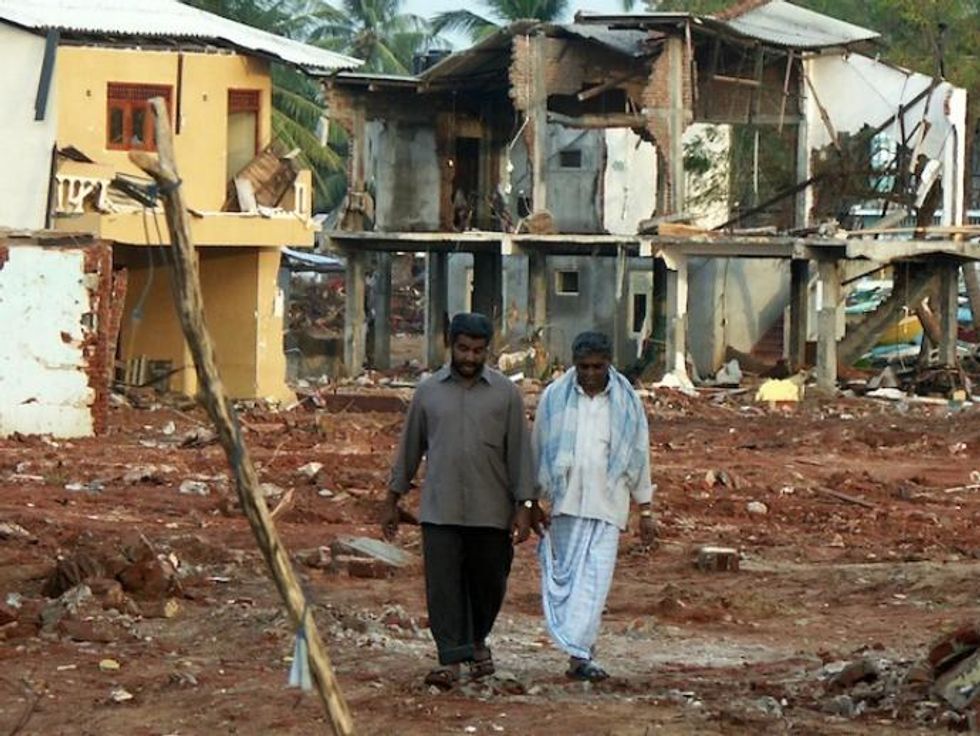

It took just 30 minutes for the killer waves to leave 350,000 dead and half a million displaced. Less than one hour for 100,000 houses to be destroyed and 200,000 people to be stripped of their livelihoods.

For many thousands of people in South Asia, the Christmas holidays will always double as a memorial for those who suffered tragic losses during the 2004 tsunami, which rushed ashore on Dec. 26 leaving a trail of tears in its wake.

The island nation of Sri Lanka was one of the worst hit, with three percent of its population affected and five percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) lost in damages.

According to the Disaster Management Center (DMC), over a million people, mainly poor families from the coastal areas, had to be evacuated.

The Northern and Eastern provinces - already struggling in the grip of the protracted civil conflict that at the time was showing no signs of abating - bore the lion's share of the destruction.

Weary from years of war, the population caught up in the fighting between government forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were battered further by the waves: according to government data, 60 percent of the tsunami's impact was concentrated on the northern and eastern coasts.

Ten years later, there are no large national monuments erected in memory of those who suffered in the aftermath of the disaster. There is not even a national archive of those who lost their lives. Small memorials dot the coast, but most are in serious need of a good paint job.

In the decade since the tsunami, Sri Lanka has undergone massive change. The nearly 30-year-old war is over; the displaced have returned to new or repaired homes; and for the majority of the island, the crashing waves have been relegated to the realm of a bad, fading nightmare.

But for the tens of thousands who lived through the catastrophe in 2004, the terror of that day will never be forgotten. And while development picks up around the island, with shining new roads leading the way to luxury tourist destinations, many are yet to come to terms with the loss, trauma and poverty that the tsunami brought into their lives.

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. Our Year-End campaign is our most important fundraiser of the year. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

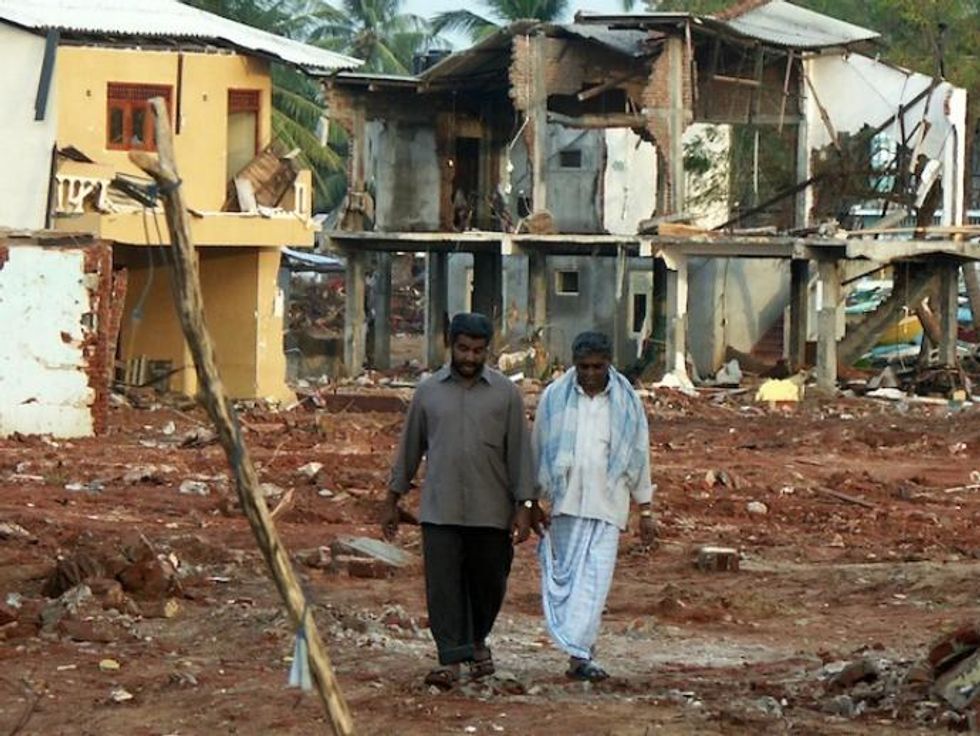

It took just 30 minutes for the killer waves to leave 350,000 dead and half a million displaced. Less than one hour for 100,000 houses to be destroyed and 200,000 people to be stripped of their livelihoods.

For many thousands of people in South Asia, the Christmas holidays will always double as a memorial for those who suffered tragic losses during the 2004 tsunami, which rushed ashore on Dec. 26 leaving a trail of tears in its wake.

The island nation of Sri Lanka was one of the worst hit, with three percent of its population affected and five percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) lost in damages.

According to the Disaster Management Center (DMC), over a million people, mainly poor families from the coastal areas, had to be evacuated.

The Northern and Eastern provinces - already struggling in the grip of the protracted civil conflict that at the time was showing no signs of abating - bore the lion's share of the destruction.

Weary from years of war, the population caught up in the fighting between government forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were battered further by the waves: according to government data, 60 percent of the tsunami's impact was concentrated on the northern and eastern coasts.

Ten years later, there are no large national monuments erected in memory of those who suffered in the aftermath of the disaster. There is not even a national archive of those who lost their lives. Small memorials dot the coast, but most are in serious need of a good paint job.

In the decade since the tsunami, Sri Lanka has undergone massive change. The nearly 30-year-old war is over; the displaced have returned to new or repaired homes; and for the majority of the island, the crashing waves have been relegated to the realm of a bad, fading nightmare.

But for the tens of thousands who lived through the catastrophe in 2004, the terror of that day will never be forgotten. And while development picks up around the island, with shining new roads leading the way to luxury tourist destinations, many are yet to come to terms with the loss, trauma and poverty that the tsunami brought into their lives.

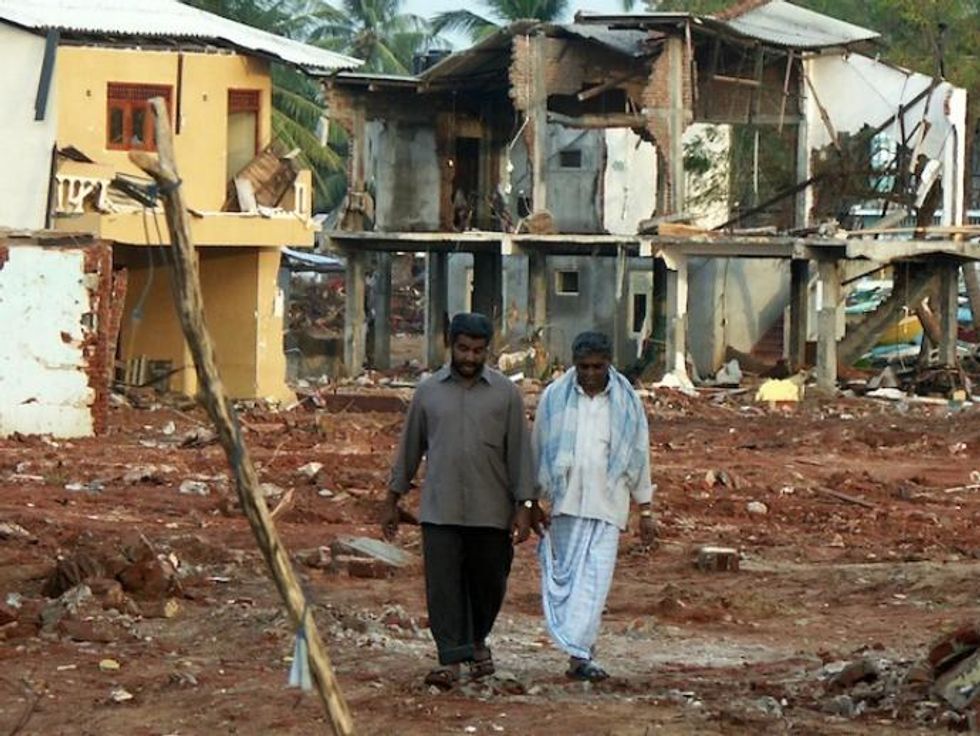

It took just 30 minutes for the killer waves to leave 350,000 dead and half a million displaced. Less than one hour for 100,000 houses to be destroyed and 200,000 people to be stripped of their livelihoods.

For many thousands of people in South Asia, the Christmas holidays will always double as a memorial for those who suffered tragic losses during the 2004 tsunami, which rushed ashore on Dec. 26 leaving a trail of tears in its wake.

The island nation of Sri Lanka was one of the worst hit, with three percent of its population affected and five percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) lost in damages.

According to the Disaster Management Center (DMC), over a million people, mainly poor families from the coastal areas, had to be evacuated.

The Northern and Eastern provinces - already struggling in the grip of the protracted civil conflict that at the time was showing no signs of abating - bore the lion's share of the destruction.

Weary from years of war, the population caught up in the fighting between government forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) were battered further by the waves: according to government data, 60 percent of the tsunami's impact was concentrated on the northern and eastern coasts.

Ten years later, there are no large national monuments erected in memory of those who suffered in the aftermath of the disaster. There is not even a national archive of those who lost their lives. Small memorials dot the coast, but most are in serious need of a good paint job.

In the decade since the tsunami, Sri Lanka has undergone massive change. The nearly 30-year-old war is over; the displaced have returned to new or repaired homes; and for the majority of the island, the crashing waves have been relegated to the realm of a bad, fading nightmare.

But for the tens of thousands who lived through the catastrophe in 2004, the terror of that day will never be forgotten. And while development picks up around the island, with shining new roads leading the way to luxury tourist destinations, many are yet to come to terms with the loss, trauma and poverty that the tsunami brought into their lives.