New Study 'Sounds Alarm' on Another Climate Feedback Loop

"What we know from this study is that warming will result in the loss of stored carbon in a wide variety of ecosystems—and that has potentially harmful effects in terms of future global warming."

The loss of Arctic sea ice has already been shown to be part of a positive feedback loop driving climate change, and a recent study published in the journal Nature puts the spotlight on what appears to be another of these feedback loops.

It has to do with soil, currently one of Earth's carbon sinks. But warming may lead to soils releasing, rather than sequestering, carbon.

As study co-author John Blair, university distinguished professor of biology at Kansas State University, explained, "Globally, soils hold more than twice as much carbon as the atmosphere, so even a relatively small increase in release of carbon from the Earth's soils can have a large impact on atmospheric greenhouse gases and future warming."

For the study, the researchers took data from over four dozen sites across the globe representing a variety of ecosystems and heated them approximately one degree Celsius.

They found that the samples from lower latitude grassland soils showed little change, but the soil samples from the colder, higher latitude ecosystems--which hold more carbon--released large amounts of carbon with the temperature increase.

The total amount of carbon lost by 2050 from these higher latitude soils could end up being the equivalent of as much as 17 percent of the expected human-caused emissions over this period, the results suggested.

The study's abstract summarizes the findings thus:

Despite the considerable uncertainty in our estimates, the direction of the global soil carbon response is consistent across all scenarios. This provides strong empirical support for the idea that rising temperatures will stimulate the net loss of soil carbon to the atmosphere, driving a positive land carbon-climate feedback that could accelerate climate change.

According to Blair, who also directs the NSF-funded Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program at Kansas State's Konza Prairie Biological Station, "This study sounds an alarm that we need to be aware of these kinds of feedbacks in order to control greenhouse gasses while they are still controllable."

The study also directs attention to soil's climate buffering potential.

"What we know from this study is that warming will result in the loss of stored carbon in a wide variety of ecosystems--and that has potentially harmful effects in terms of future global warming," Blair noted. "At the same time, it also highlights the potential role that the soil could play in storing carbon and helping to mitigate climate change."

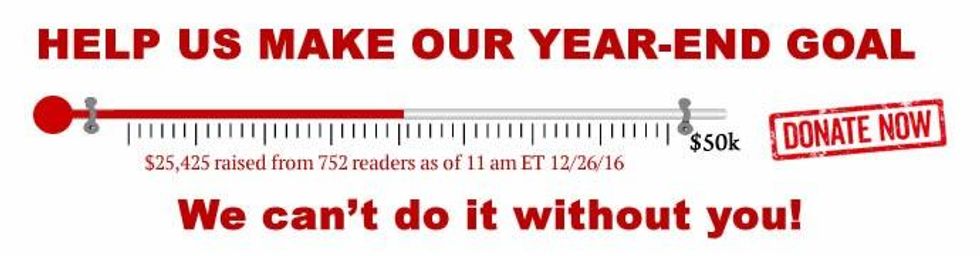

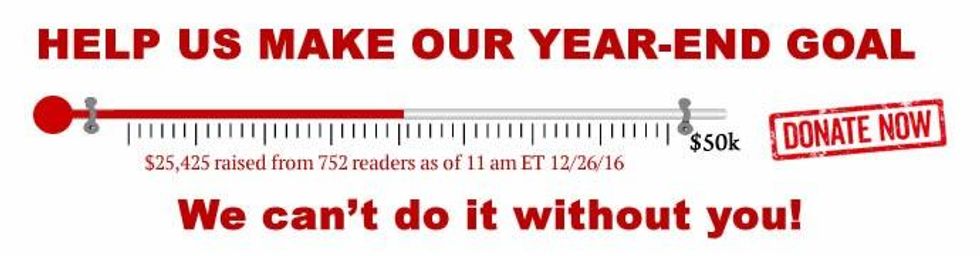

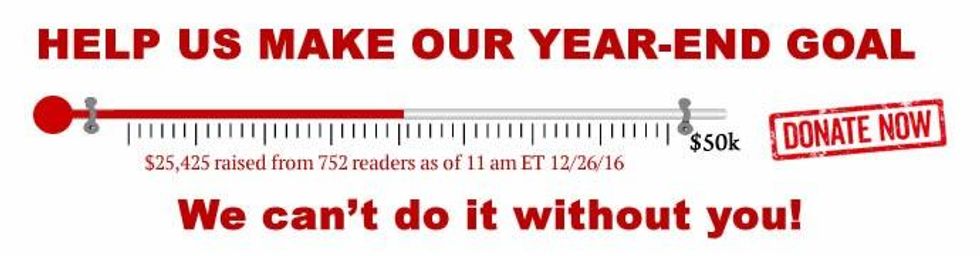

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The loss of Arctic sea ice has already been shown to be part of a positive feedback loop driving climate change, and a recent study published in the journal Nature puts the spotlight on what appears to be another of these feedback loops.

It has to do with soil, currently one of Earth's carbon sinks. But warming may lead to soils releasing, rather than sequestering, carbon.

As study co-author John Blair, university distinguished professor of biology at Kansas State University, explained, "Globally, soils hold more than twice as much carbon as the atmosphere, so even a relatively small increase in release of carbon from the Earth's soils can have a large impact on atmospheric greenhouse gases and future warming."

For the study, the researchers took data from over four dozen sites across the globe representing a variety of ecosystems and heated them approximately one degree Celsius.

They found that the samples from lower latitude grassland soils showed little change, but the soil samples from the colder, higher latitude ecosystems--which hold more carbon--released large amounts of carbon with the temperature increase.

The total amount of carbon lost by 2050 from these higher latitude soils could end up being the equivalent of as much as 17 percent of the expected human-caused emissions over this period, the results suggested.

The study's abstract summarizes the findings thus:

Despite the considerable uncertainty in our estimates, the direction of the global soil carbon response is consistent across all scenarios. This provides strong empirical support for the idea that rising temperatures will stimulate the net loss of soil carbon to the atmosphere, driving a positive land carbon-climate feedback that could accelerate climate change.

According to Blair, who also directs the NSF-funded Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program at Kansas State's Konza Prairie Biological Station, "This study sounds an alarm that we need to be aware of these kinds of feedbacks in order to control greenhouse gasses while they are still controllable."

The study also directs attention to soil's climate buffering potential.

"What we know from this study is that warming will result in the loss of stored carbon in a wide variety of ecosystems--and that has potentially harmful effects in terms of future global warming," Blair noted. "At the same time, it also highlights the potential role that the soil could play in storing carbon and helping to mitigate climate change."

The loss of Arctic sea ice has already been shown to be part of a positive feedback loop driving climate change, and a recent study published in the journal Nature puts the spotlight on what appears to be another of these feedback loops.

It has to do with soil, currently one of Earth's carbon sinks. But warming may lead to soils releasing, rather than sequestering, carbon.

As study co-author John Blair, university distinguished professor of biology at Kansas State University, explained, "Globally, soils hold more than twice as much carbon as the atmosphere, so even a relatively small increase in release of carbon from the Earth's soils can have a large impact on atmospheric greenhouse gases and future warming."

For the study, the researchers took data from over four dozen sites across the globe representing a variety of ecosystems and heated them approximately one degree Celsius.

They found that the samples from lower latitude grassland soils showed little change, but the soil samples from the colder, higher latitude ecosystems--which hold more carbon--released large amounts of carbon with the temperature increase.

The total amount of carbon lost by 2050 from these higher latitude soils could end up being the equivalent of as much as 17 percent of the expected human-caused emissions over this period, the results suggested.

The study's abstract summarizes the findings thus:

Despite the considerable uncertainty in our estimates, the direction of the global soil carbon response is consistent across all scenarios. This provides strong empirical support for the idea that rising temperatures will stimulate the net loss of soil carbon to the atmosphere, driving a positive land carbon-climate feedback that could accelerate climate change.

According to Blair, who also directs the NSF-funded Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program at Kansas State's Konza Prairie Biological Station, "This study sounds an alarm that we need to be aware of these kinds of feedbacks in order to control greenhouse gasses while they are still controllable."

The study also directs attention to soil's climate buffering potential.

"What we know from this study is that warming will result in the loss of stored carbon in a wide variety of ecosystems--and that has potentially harmful effects in terms of future global warming," Blair noted. "At the same time, it also highlights the potential role that the soil could play in storing carbon and helping to mitigate climate change."