SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Whither the American Dream?

It may not be totally dead, but a new study suggests that it is certainly on life support.

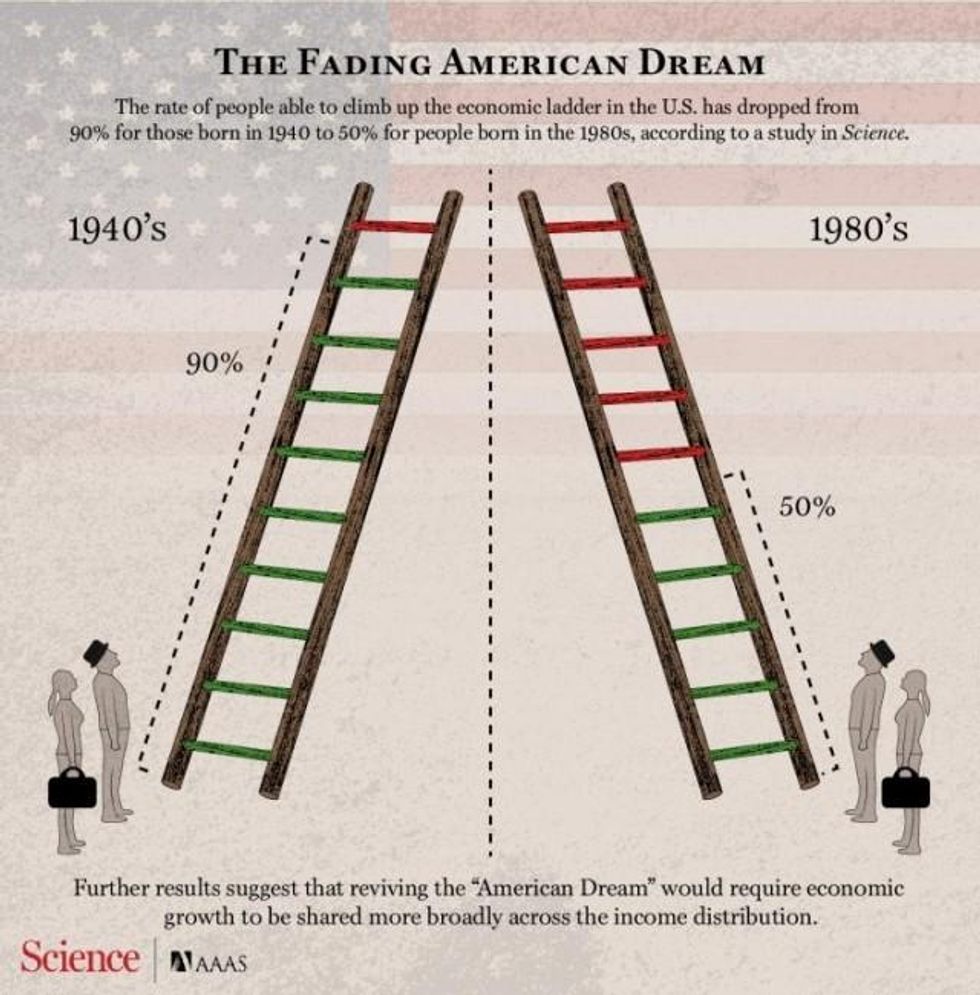

Published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science journal Science, the team of researchers led by Raj Chetty and David Grusky of Stanford University used data from federal income tax returns and U.S. Census and Current Population Surveys to look at trends of this "absolute mobility," or earning more than one's parents.

What they found was a dramatic decline over the past several decades. While nearly all--over 90 percent--of children born in 1940 were able to earn more than their parents, that figure drops to 50 percent for children born in the 1980s.

The authors write that the decline was particularly acute "in the industrial Midwest," states like Michigan, and hit the middle class hardest, though they note "that declines in absolute mobility have been a systematic, widespread phenomenon throughout the United States since 1940."

Thus, a big part of reversing the trend means "more equal economic redistribution," the researchers conclude.

Noting the economic benefits that have been reaped most by those at the upper echelons, noted commentator Bill Moyers wrote months ago of "an ugly truth about America: inequality matters. It slows economic growth, undermines health, erodes social cohesion and solidarity, and starves education."

It was a major theme of the presidential campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who continues to rail against the country's "massive income and wealth inequality," and condemned President Donald Trump's budget blueprint last month as "morally obsence" for including "unacceptably painful cuts to programs that senior citizens, children, persons with disabilities, and working people rely on to feed their families, heat their homes, put food on the table, and educate their children."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Whither the American Dream?

It may not be totally dead, but a new study suggests that it is certainly on life support.

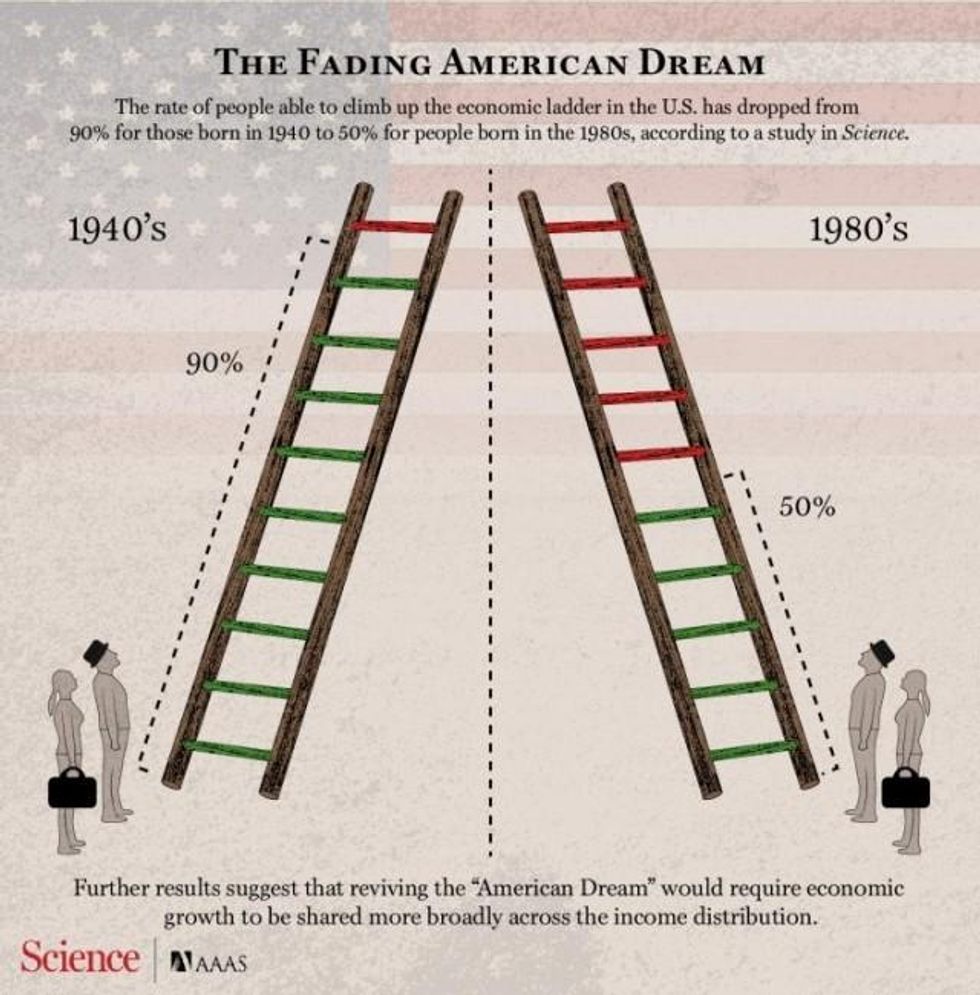

Published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science journal Science, the team of researchers led by Raj Chetty and David Grusky of Stanford University used data from federal income tax returns and U.S. Census and Current Population Surveys to look at trends of this "absolute mobility," or earning more than one's parents.

What they found was a dramatic decline over the past several decades. While nearly all--over 90 percent--of children born in 1940 were able to earn more than their parents, that figure drops to 50 percent for children born in the 1980s.

The authors write that the decline was particularly acute "in the industrial Midwest," states like Michigan, and hit the middle class hardest, though they note "that declines in absolute mobility have been a systematic, widespread phenomenon throughout the United States since 1940."

Thus, a big part of reversing the trend means "more equal economic redistribution," the researchers conclude.

Noting the economic benefits that have been reaped most by those at the upper echelons, noted commentator Bill Moyers wrote months ago of "an ugly truth about America: inequality matters. It slows economic growth, undermines health, erodes social cohesion and solidarity, and starves education."

It was a major theme of the presidential campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who continues to rail against the country's "massive income and wealth inequality," and condemned President Donald Trump's budget blueprint last month as "morally obsence" for including "unacceptably painful cuts to programs that senior citizens, children, persons with disabilities, and working people rely on to feed their families, heat their homes, put food on the table, and educate their children."

Whither the American Dream?

It may not be totally dead, but a new study suggests that it is certainly on life support.

Published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science journal Science, the team of researchers led by Raj Chetty and David Grusky of Stanford University used data from federal income tax returns and U.S. Census and Current Population Surveys to look at trends of this "absolute mobility," or earning more than one's parents.

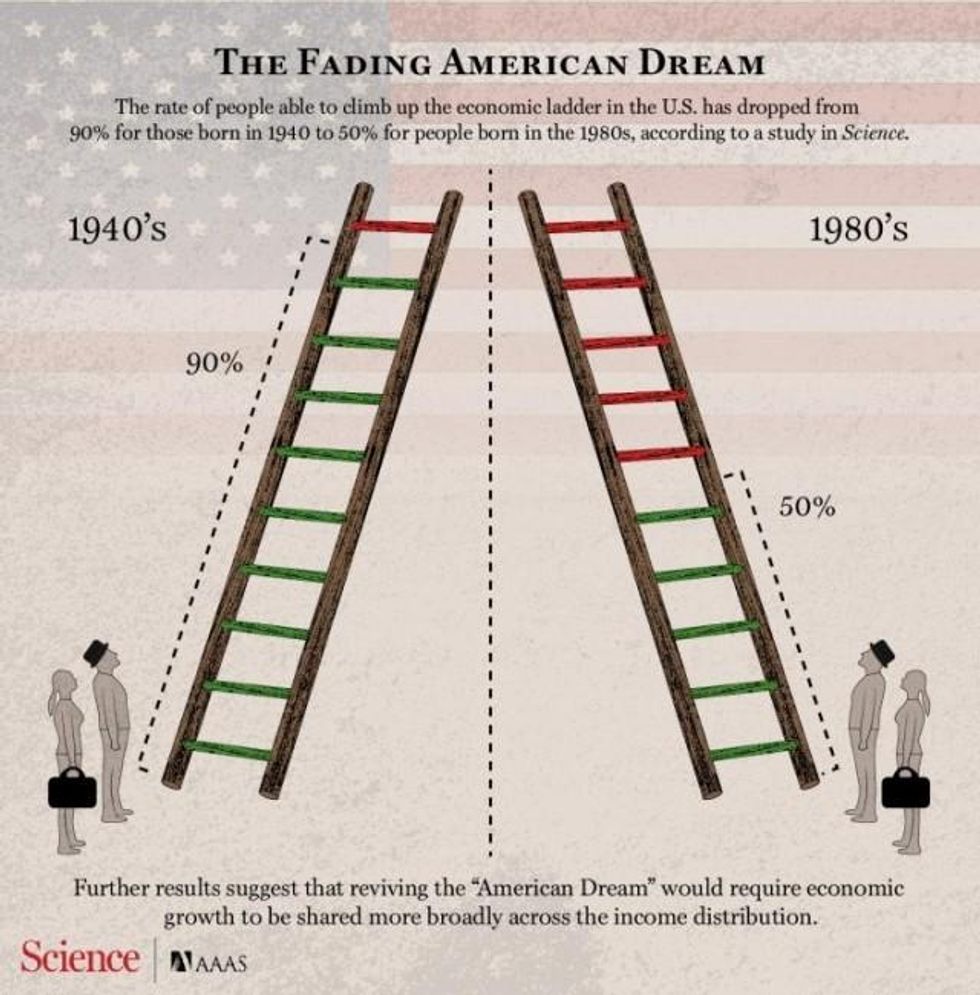

What they found was a dramatic decline over the past several decades. While nearly all--over 90 percent--of children born in 1940 were able to earn more than their parents, that figure drops to 50 percent for children born in the 1980s.

The authors write that the decline was particularly acute "in the industrial Midwest," states like Michigan, and hit the middle class hardest, though they note "that declines in absolute mobility have been a systematic, widespread phenomenon throughout the United States since 1940."

Thus, a big part of reversing the trend means "more equal economic redistribution," the researchers conclude.

Noting the economic benefits that have been reaped most by those at the upper echelons, noted commentator Bill Moyers wrote months ago of "an ugly truth about America: inequality matters. It slows economic growth, undermines health, erodes social cohesion and solidarity, and starves education."

It was a major theme of the presidential campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), who continues to rail against the country's "massive income and wealth inequality," and condemned President Donald Trump's budget blueprint last month as "morally obsence" for including "unacceptably painful cuts to programs that senior citizens, children, persons with disabilities, and working people rely on to feed their families, heat their homes, put food on the table, and educate their children."