SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

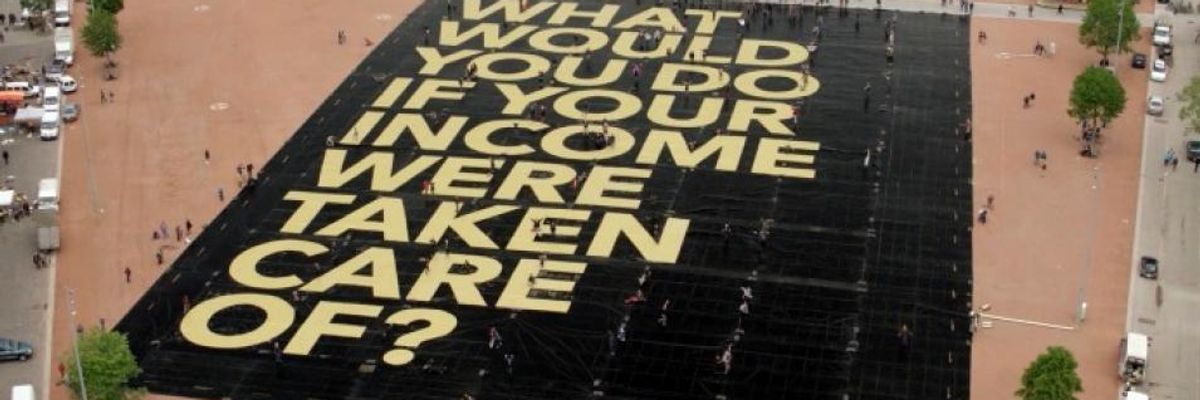

"Curbing advertising, taxing carbon, a basic income, and a shorter work week" can be part of a strategy of "planned de-growth." (Photo: Generation Grundeinkommen/flickr/cc)

As some tech giants throw their weight behind the idea of a universal basic income, one anthropologist says it's a key component of a strategy to break the "addiction to economic growth [that] is killing us" and the planet.

Offering his views this week on BBC's "Viewsnight," Jason Hickel, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics and author of books including The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, says "we can't have infinite growth on a finite planet."

That argument--which others have made as well--should be clear by evidence of the "climate change, deforestation, and rapid rates of extinction" taking hold, he says.

The primary blame, according to Hickel, rests with "over-consumption in rich countries," and addressing that entails "planned de-growth," which will put the reins on "our plunder of the earth."

Hickel stresses that he's not referring to austerity, as the goal of "de-growth" is to "increase human well-being and happiness while reducing our economic footprint."

A blueprint to achieve that goal, he says, includes "curbing advertising, taxing carbon, a basic income, and a shorter work week."

"We need an economic model that promotes human flourishing in harmony with the planet on which we depend," he says.

The idea of a universal basic income is gaining attention in the U.S. thanks to a recent resolution put forth in Hawaii, and Philip Alston, U.N. Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said earlier this summer that a basic income is "a bold and imaginative solution" amidst growing economic insecurity.

Laura Williams of the U.K.-based advocacy group Global Justice Now recently asked, "Has the time for universal basic income come?"

According to Hickel, it may be more necessary than ever given the era of President Donald Trump. Hickel wrote in an-op ed at the Guardian this year that

a basic income might defeat the scarcity mindset that has seeped so deep into our culture, freeing us from the imperatives of competition and allowing us to be more open and generous people. If extended universally, across borders, it might help instill a sense of solidarity--that we're all in this together, and all have an equal right to the planet. It might ease the anxieties that gave us Brexit and Trump, and take the wind out of the fascist tendencies rising elsewhere in nativism that is spreading across much of the world.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

As some tech giants throw their weight behind the idea of a universal basic income, one anthropologist says it's a key component of a strategy to break the "addiction to economic growth [that] is killing us" and the planet.

Offering his views this week on BBC's "Viewsnight," Jason Hickel, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics and author of books including The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, says "we can't have infinite growth on a finite planet."

That argument--which others have made as well--should be clear by evidence of the "climate change, deforestation, and rapid rates of extinction" taking hold, he says.

The primary blame, according to Hickel, rests with "over-consumption in rich countries," and addressing that entails "planned de-growth," which will put the reins on "our plunder of the earth."

Hickel stresses that he's not referring to austerity, as the goal of "de-growth" is to "increase human well-being and happiness while reducing our economic footprint."

A blueprint to achieve that goal, he says, includes "curbing advertising, taxing carbon, a basic income, and a shorter work week."

"We need an economic model that promotes human flourishing in harmony with the planet on which we depend," he says.

The idea of a universal basic income is gaining attention in the U.S. thanks to a recent resolution put forth in Hawaii, and Philip Alston, U.N. Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said earlier this summer that a basic income is "a bold and imaginative solution" amidst growing economic insecurity.

Laura Williams of the U.K.-based advocacy group Global Justice Now recently asked, "Has the time for universal basic income come?"

According to Hickel, it may be more necessary than ever given the era of President Donald Trump. Hickel wrote in an-op ed at the Guardian this year that

a basic income might defeat the scarcity mindset that has seeped so deep into our culture, freeing us from the imperatives of competition and allowing us to be more open and generous people. If extended universally, across borders, it might help instill a sense of solidarity--that we're all in this together, and all have an equal right to the planet. It might ease the anxieties that gave us Brexit and Trump, and take the wind out of the fascist tendencies rising elsewhere in nativism that is spreading across much of the world.

As some tech giants throw their weight behind the idea of a universal basic income, one anthropologist says it's a key component of a strategy to break the "addiction to economic growth [that] is killing us" and the planet.

Offering his views this week on BBC's "Viewsnight," Jason Hickel, an anthropologist at the London School of Economics and author of books including The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, says "we can't have infinite growth on a finite planet."

That argument--which others have made as well--should be clear by evidence of the "climate change, deforestation, and rapid rates of extinction" taking hold, he says.

The primary blame, according to Hickel, rests with "over-consumption in rich countries," and addressing that entails "planned de-growth," which will put the reins on "our plunder of the earth."

Hickel stresses that he's not referring to austerity, as the goal of "de-growth" is to "increase human well-being and happiness while reducing our economic footprint."

A blueprint to achieve that goal, he says, includes "curbing advertising, taxing carbon, a basic income, and a shorter work week."

"We need an economic model that promotes human flourishing in harmony with the planet on which we depend," he says.

The idea of a universal basic income is gaining attention in the U.S. thanks to a recent resolution put forth in Hawaii, and Philip Alston, U.N. Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said earlier this summer that a basic income is "a bold and imaginative solution" amidst growing economic insecurity.

Laura Williams of the U.K.-based advocacy group Global Justice Now recently asked, "Has the time for universal basic income come?"

According to Hickel, it may be more necessary than ever given the era of President Donald Trump. Hickel wrote in an-op ed at the Guardian this year that

a basic income might defeat the scarcity mindset that has seeped so deep into our culture, freeing us from the imperatives of competition and allowing us to be more open and generous people. If extended universally, across borders, it might help instill a sense of solidarity--that we're all in this together, and all have an equal right to the planet. It might ease the anxieties that gave us Brexit and Trump, and take the wind out of the fascist tendencies rising elsewhere in nativism that is spreading across much of the world.