SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

A new study by the Brennan Center for Justice revealed that 17 million Americans were dropped from voter rolls between 2016 and 2018. (Photo: Hero Images)

Millions of Americans are still suffering the consequences of the 2013 Supreme Court decision that loosened restrictions of the Voting Rights Act, giving states with long histories of voter discrimination free rein to purge voters from their rolls without federal oversight.

The Brennan Center for Justice released a study Thursday showing that 17 million Americans were dropped from voter rolls between 2016 and 2018--almost four million more than the number purged between 2006 and 2008.

The problem was most pronounced in counties and election precincts with a history of racial oppression and voter suppression. In such areas voters were kicked off rolls at a rate 40 percent higher than places which have protected voting rights more consistently.

Following the Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, counties with histories of discrimination no longer have to obtain "pre-clearance," or approval from the Department of Justice (DOJ), before they make changes to voting procedures--allowing them to slash their voter rolls liberally, often resulting in voter suppression of eligible voters.

According to the Brennan Center, Shelby County single-handedly pushed two million people off voter rolls across the country over four years after the case was decided.

"The effect of the Supreme Court's 2013 decision has not abated," researcher Kevin Morris wrote Friday.

The Brennan Center said that while there are legitimate reasons for removing names from a state's voter database, such as a relocation to another state or a death, many voters' names--especially those of minority voters--are purged even though they meet the state's requirements for casting a ballot.

"In big states like California and Texas, multiple individuals can have the same name and date of birth, making it hard to be sure that the right voter is being purged when perfect data are unavailable," wrote Morris. "Troublingly, minority voters are more likely to share names than white voters, potentially exposing them to a greater risk of being purged."

"Voters often do not realize they have been purged until they try to cast a ballot on Election Day--after it's already too late," Morris added.

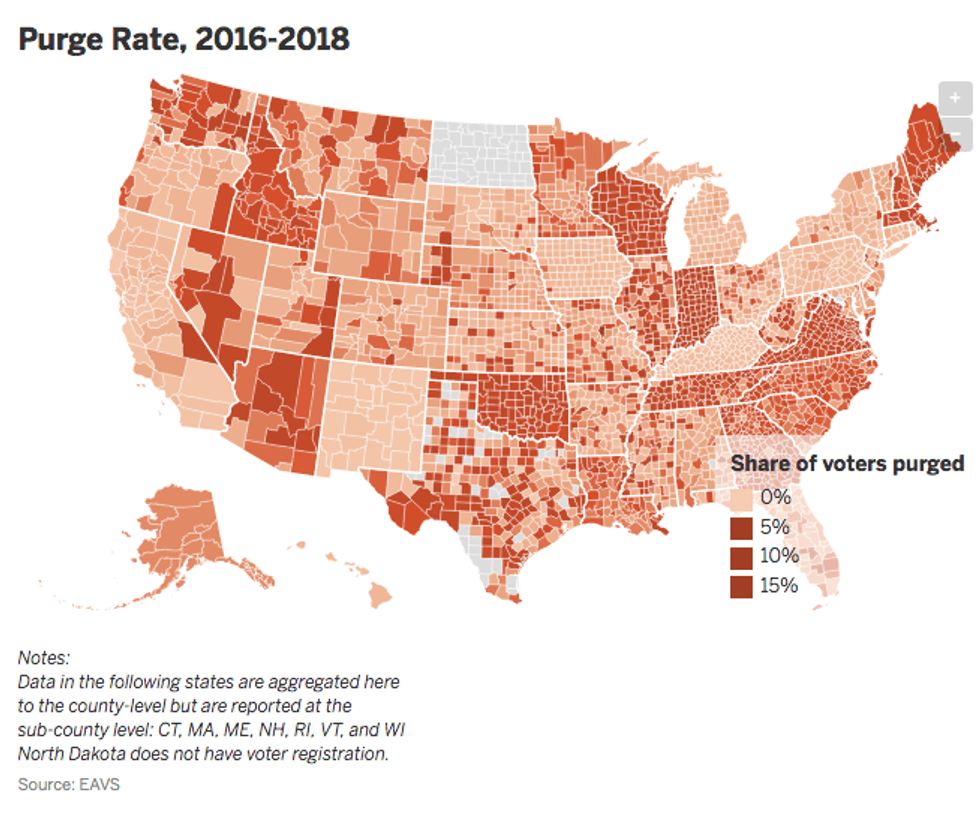

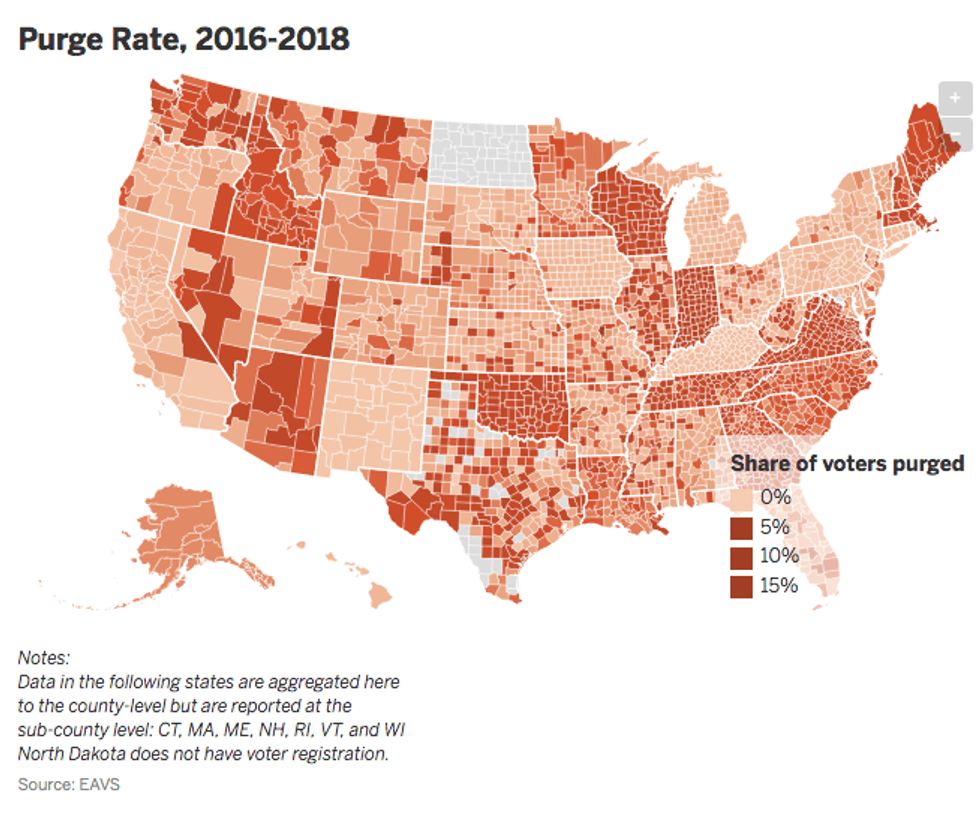

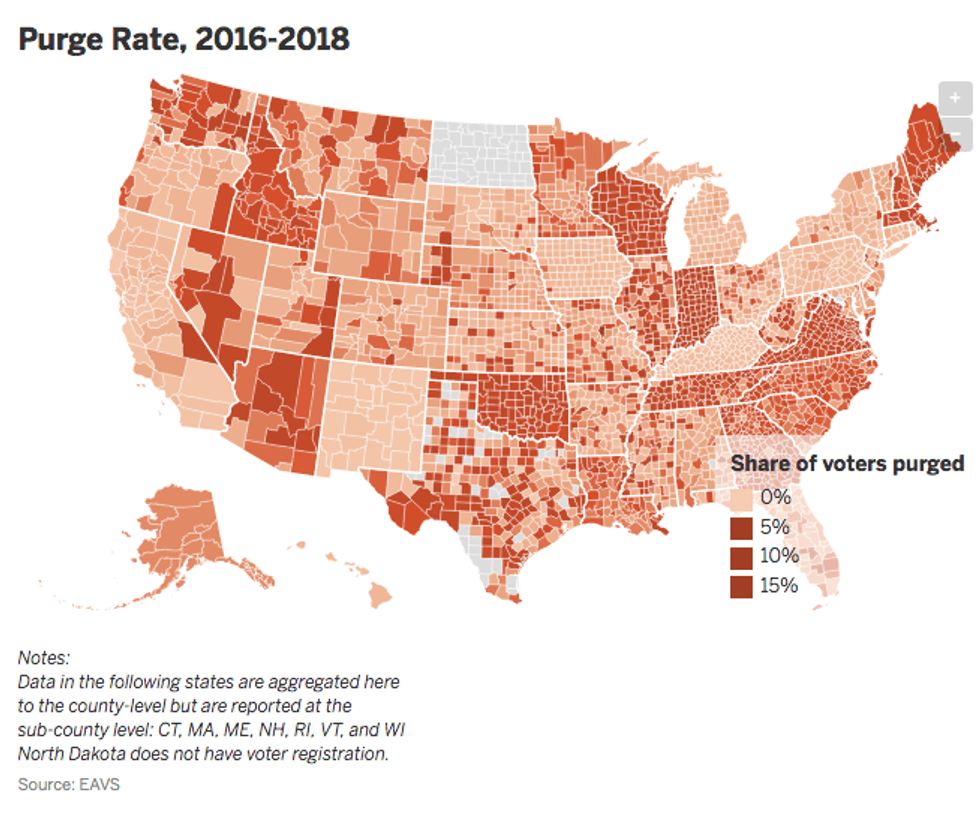

In its report, the Brennan Center included a map showing the counties where the most voters were dropped from the rolls.

Indiana purged close to a quarter of voters from its rolls between 2016 and 2018, while Wisconsin and Virginia dropped about 14 percent of voters. More than 10 percent of voters in Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Maine were purged from voter databases.

High rates of voter purging in some states have made headlines in recent months. Georgia's Republican Gov. Mark Kemp came under fire during his election campaign last year for overseeing, as secretary of state, the purging of more than 100,000 voters from the state rolls, including many people of color.

In Ohio, Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown was among those protesting this week against an impending purge of as many as 235,000 voters from the state's rolls.

\u201cWe should make it easier -- not harder -- to vote. Add your name to mine to make sure every Ohio voter is heard when they go to the ballot box - SB\nhttps://t.co/RRPUwkfFVO\u201d— Sherrod Brown (@Sherrod Brown) 1564748981

\u201cUnsurprising but disappointing: after getting the okay from #SCOTUS last year, Ohio is getting ready to purge 235,000 voters from the rolls if they don't reply to a notice from the state. https://t.co/mppqIbE9Zc\u201d— Campaign Legal Center (@Campaign Legal Center) 1564529702

Across the country, the Brennan Center said Friday, election officials must embrace efforts to make voting easier, not harder, and ensure eligible voters don't show up to the polls in upcoming elections only to find out that their name has been purged.

"Election administrators must be transparent about how they are deciding what names to remove from the rolls," said the organization. "They must be diligent in their efforts to avoid erroneously purging voters. And they should push for reforms like automatic voter registration and election day registration, which keep voters' registration records up to date."

"Election Day is often too late to discover that a person has been wrongfully purged," the group added.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Millions of Americans are still suffering the consequences of the 2013 Supreme Court decision that loosened restrictions of the Voting Rights Act, giving states with long histories of voter discrimination free rein to purge voters from their rolls without federal oversight.

The Brennan Center for Justice released a study Thursday showing that 17 million Americans were dropped from voter rolls between 2016 and 2018--almost four million more than the number purged between 2006 and 2008.

The problem was most pronounced in counties and election precincts with a history of racial oppression and voter suppression. In such areas voters were kicked off rolls at a rate 40 percent higher than places which have protected voting rights more consistently.

Following the Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, counties with histories of discrimination no longer have to obtain "pre-clearance," or approval from the Department of Justice (DOJ), before they make changes to voting procedures--allowing them to slash their voter rolls liberally, often resulting in voter suppression of eligible voters.

According to the Brennan Center, Shelby County single-handedly pushed two million people off voter rolls across the country over four years after the case was decided.

"The effect of the Supreme Court's 2013 decision has not abated," researcher Kevin Morris wrote Friday.

The Brennan Center said that while there are legitimate reasons for removing names from a state's voter database, such as a relocation to another state or a death, many voters' names--especially those of minority voters--are purged even though they meet the state's requirements for casting a ballot.

"In big states like California and Texas, multiple individuals can have the same name and date of birth, making it hard to be sure that the right voter is being purged when perfect data are unavailable," wrote Morris. "Troublingly, minority voters are more likely to share names than white voters, potentially exposing them to a greater risk of being purged."

"Voters often do not realize they have been purged until they try to cast a ballot on Election Day--after it's already too late," Morris added.

In its report, the Brennan Center included a map showing the counties where the most voters were dropped from the rolls.

Indiana purged close to a quarter of voters from its rolls between 2016 and 2018, while Wisconsin and Virginia dropped about 14 percent of voters. More than 10 percent of voters in Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Maine were purged from voter databases.

High rates of voter purging in some states have made headlines in recent months. Georgia's Republican Gov. Mark Kemp came under fire during his election campaign last year for overseeing, as secretary of state, the purging of more than 100,000 voters from the state rolls, including many people of color.

In Ohio, Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown was among those protesting this week against an impending purge of as many as 235,000 voters from the state's rolls.

\u201cWe should make it easier -- not harder -- to vote. Add your name to mine to make sure every Ohio voter is heard when they go to the ballot box - SB\nhttps://t.co/RRPUwkfFVO\u201d— Sherrod Brown (@Sherrod Brown) 1564748981

\u201cUnsurprising but disappointing: after getting the okay from #SCOTUS last year, Ohio is getting ready to purge 235,000 voters from the rolls if they don't reply to a notice from the state. https://t.co/mppqIbE9Zc\u201d— Campaign Legal Center (@Campaign Legal Center) 1564529702

Across the country, the Brennan Center said Friday, election officials must embrace efforts to make voting easier, not harder, and ensure eligible voters don't show up to the polls in upcoming elections only to find out that their name has been purged.

"Election administrators must be transparent about how they are deciding what names to remove from the rolls," said the organization. "They must be diligent in their efforts to avoid erroneously purging voters. And they should push for reforms like automatic voter registration and election day registration, which keep voters' registration records up to date."

"Election Day is often too late to discover that a person has been wrongfully purged," the group added.

Millions of Americans are still suffering the consequences of the 2013 Supreme Court decision that loosened restrictions of the Voting Rights Act, giving states with long histories of voter discrimination free rein to purge voters from their rolls without federal oversight.

The Brennan Center for Justice released a study Thursday showing that 17 million Americans were dropped from voter rolls between 2016 and 2018--almost four million more than the number purged between 2006 and 2008.

The problem was most pronounced in counties and election precincts with a history of racial oppression and voter suppression. In such areas voters were kicked off rolls at a rate 40 percent higher than places which have protected voting rights more consistently.

Following the Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, counties with histories of discrimination no longer have to obtain "pre-clearance," or approval from the Department of Justice (DOJ), before they make changes to voting procedures--allowing them to slash their voter rolls liberally, often resulting in voter suppression of eligible voters.

According to the Brennan Center, Shelby County single-handedly pushed two million people off voter rolls across the country over four years after the case was decided.

"The effect of the Supreme Court's 2013 decision has not abated," researcher Kevin Morris wrote Friday.

The Brennan Center said that while there are legitimate reasons for removing names from a state's voter database, such as a relocation to another state or a death, many voters' names--especially those of minority voters--are purged even though they meet the state's requirements for casting a ballot.

"In big states like California and Texas, multiple individuals can have the same name and date of birth, making it hard to be sure that the right voter is being purged when perfect data are unavailable," wrote Morris. "Troublingly, minority voters are more likely to share names than white voters, potentially exposing them to a greater risk of being purged."

"Voters often do not realize they have been purged until they try to cast a ballot on Election Day--after it's already too late," Morris added.

In its report, the Brennan Center included a map showing the counties where the most voters were dropped from the rolls.

Indiana purged close to a quarter of voters from its rolls between 2016 and 2018, while Wisconsin and Virginia dropped about 14 percent of voters. More than 10 percent of voters in Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Maine were purged from voter databases.

High rates of voter purging in some states have made headlines in recent months. Georgia's Republican Gov. Mark Kemp came under fire during his election campaign last year for overseeing, as secretary of state, the purging of more than 100,000 voters from the state rolls, including many people of color.

In Ohio, Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown was among those protesting this week against an impending purge of as many as 235,000 voters from the state's rolls.

\u201cWe should make it easier -- not harder -- to vote. Add your name to mine to make sure every Ohio voter is heard when they go to the ballot box - SB\nhttps://t.co/RRPUwkfFVO\u201d— Sherrod Brown (@Sherrod Brown) 1564748981

\u201cUnsurprising but disappointing: after getting the okay from #SCOTUS last year, Ohio is getting ready to purge 235,000 voters from the rolls if they don't reply to a notice from the state. https://t.co/mppqIbE9Zc\u201d— Campaign Legal Center (@Campaign Legal Center) 1564529702

Across the country, the Brennan Center said Friday, election officials must embrace efforts to make voting easier, not harder, and ensure eligible voters don't show up to the polls in upcoming elections only to find out that their name has been purged.

"Election administrators must be transparent about how they are deciding what names to remove from the rolls," said the organization. "They must be diligent in their efforts to avoid erroneously purging voters. And they should push for reforms like automatic voter registration and election day registration, which keep voters' registration records up to date."

"Election Day is often too late to discover that a person has been wrongfully purged," the group added.