U.S. Coast Guard crews work to put out a fire during the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

U.S. Coast Guard crews work to put out a fire during the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. (Photo: U.S. Coast Guard)

A decade after the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill unleashed roughly 200 million of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, ecological damage remains. And with lessons from the disaster clearly unlearned ten years and two administrations later, environmental groups say the need to ditch a fossil fuel-based energy system is more urgent than ever.

\u201cOn this day ten years ago, hundreds of millions gallons of oil spewed into the Gulf.\n\nToday we're joining groups in calling for a stop to the expansion of offshore drilling!\n\nIt's not an if, but a when we have the next #DeepwaterHorizon.\n\n#BP10\n\nhttps://t.co/P9yg8uhigB\u201d— Friends of the Earth (Action) (@Friends of the Earth (Action)) 1587409192

As the Associated Pressreported Monday, "black oil no longer visibly stains the beaches and estuaries" along the Gulf, but that clean image betrays a bevy of problems in and out of the waters.

"We will see environmental impacts from this for the rest of our lifetimes," Steven A. Murawski, who was chief scientist of the National Marine Fisheries Service when the Macondo well blew, told AP.

CNNdrew attention Monday to some of those consequences, pointing to research showing oil pollution in thousands of fish in the Gulf in the years following the disaster.

The research was carried out between 2011 and 2018, sampling more than 2,500 individual fish that belonged to 91 species living in 359 different locations in the Gulf. All of them contained oil exposure. [...]

The oil pollution in the fish included levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, known as PAHs. The toxic crude oil component was found in the bile of the fish. Fish bile, found in their livers, stores waste and aids digestion. [...]

While high levels of PAHs were expected in tilefish, which live in seafloor burrows where oil and PAHs are still found, the levels have been increasing over time.

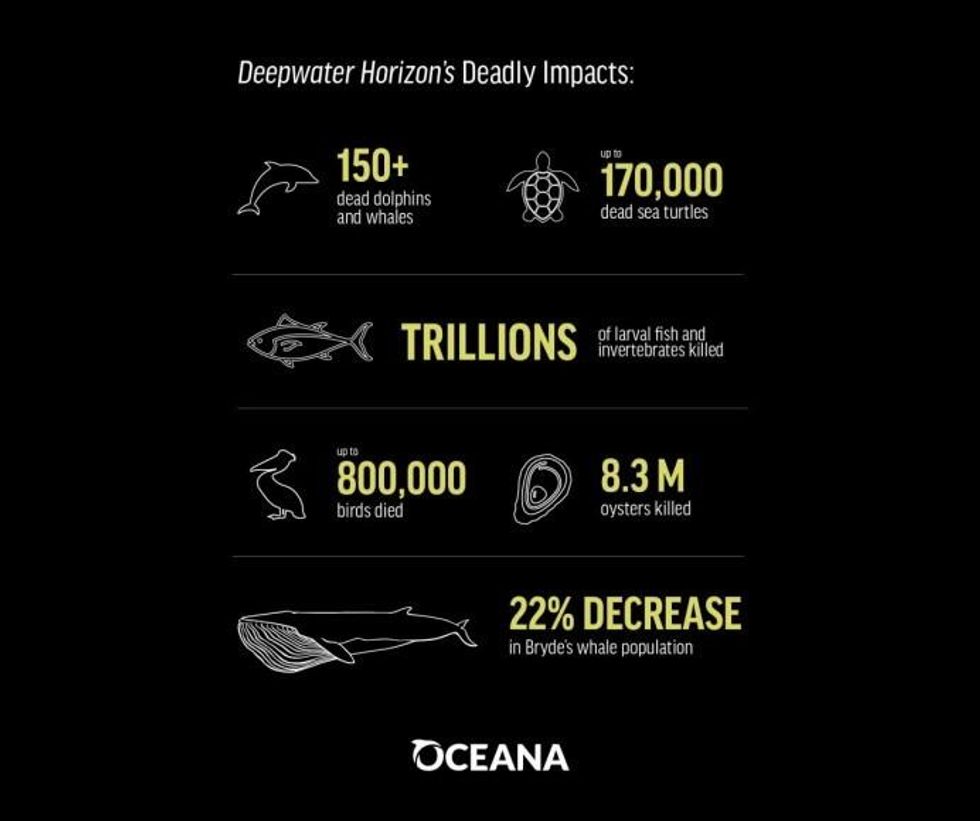

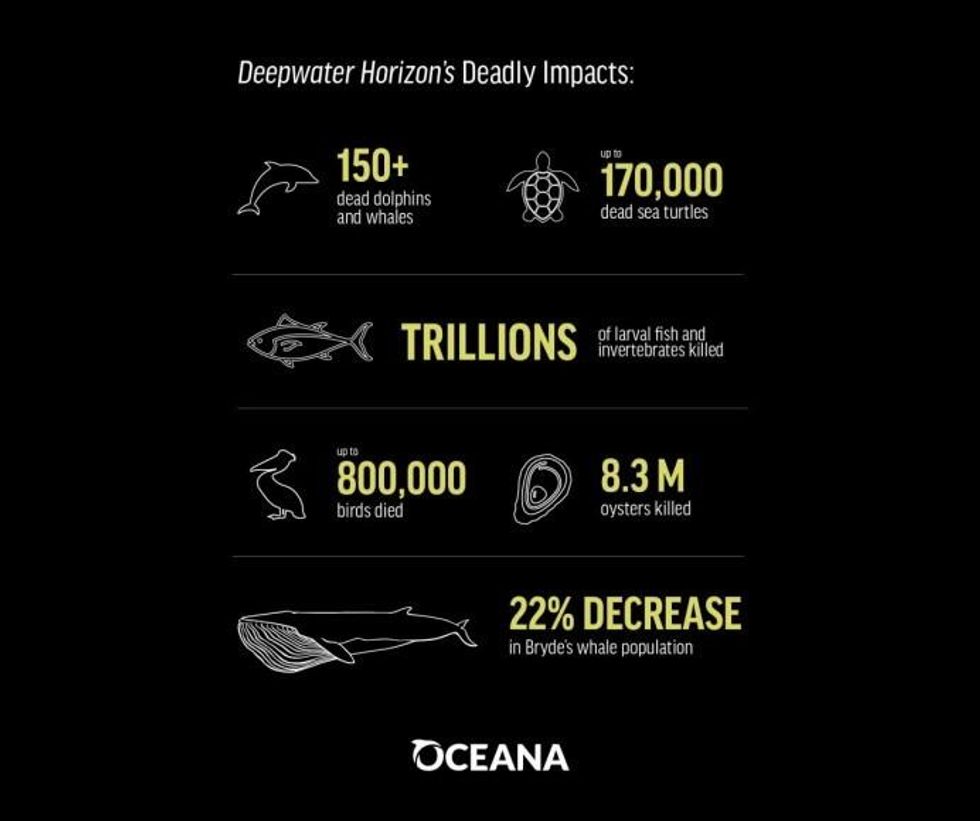

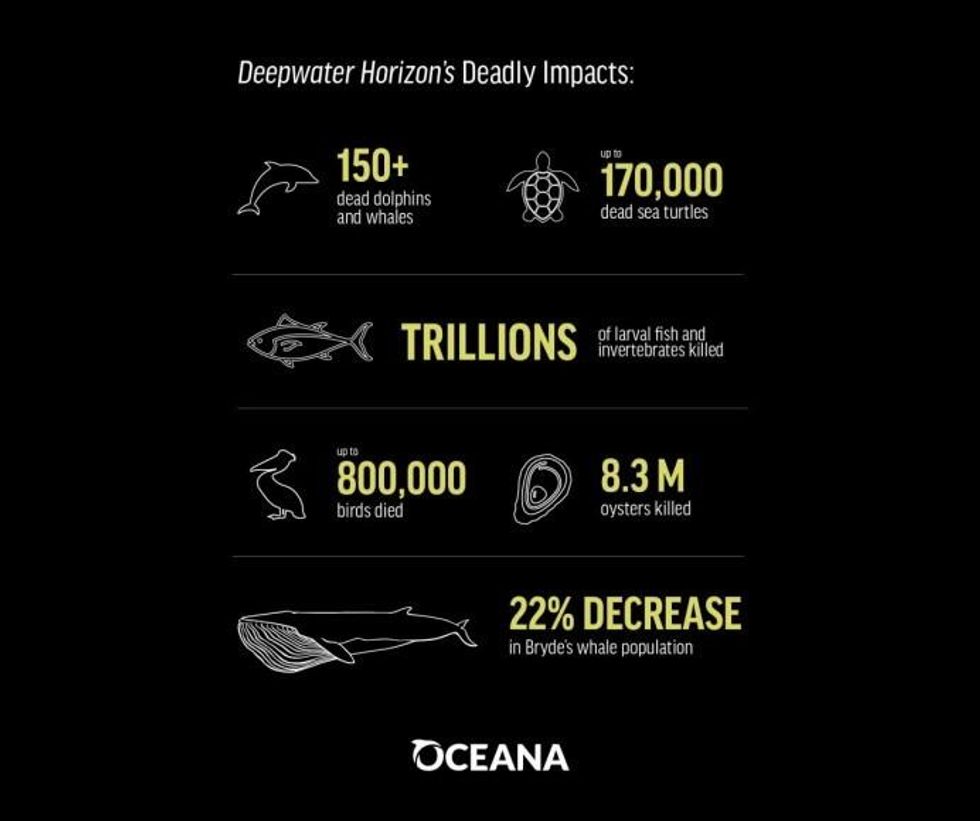

The ecological impacts, both from the oil and the unprecedented use of "dispersants," were a major focus of a report out last week from Oceana, which included this summary of the deadly impacts to sea life:

"The fact that you don't see it on the beaches, or you don't see it floating around ... doesn't mean that it's gone," Clifton Nunnally, a research scientist with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, told Oceana about the oil from the 2010 spill. "It means that it's moved to a new ecosystem. And it's a system that operates on the order of millennia, not just years or decades. So, the recovery for a deep-sea ecosystem like this could be a longterm process."

Despite those impacts, as well as ongoing harm to local communities, it appears nothing has been learned. The chance of a similar oil disaster happening is just as likely now as it was 10 years ago, said Oceana.

The offshore oil drilling industry says it's put measures in place to make sure that can't happen--a claim critics like Oceana reject.

Among the problems the green groups point to as exacerbating the danger of another major spill is the Trump administration's move last May gutting offshore drilling regulations aimed at preventing a Deepwater Horizon-style disaster, including a weakening of a measure to prevent a well blowout.

And it's not just advocacy groups sounding alarm. As the New York Timesreported Monday,

[A]ll seven members of the bipartisan national commission set up to find the roots of the disaster and prevent a repeat said many of their recommendations were never taken seriously. As drilling moves farther offshore and deeper underwater, they said, another spill of equally disastrous proportions is possible.

"Offshore drilling is still as dirty and dangerous as it was 10 years ago," Diane Hoskins, Oceana campaign director, said in a statement last week.

Contributing to such fears is the Trump administration's rejection of science, deregulatory agenda, and push for increased fossil fuel extraction.

"Instead of learning lessons from the BP disaster, President Trump is proposing to radically expand offshore drilling, while dismantling the few protections put in place as a result of the catastrophic blowout," added Hoskins.

That adds up to a pretty good decade for the offshore industry. The New York Times editorial board wrote Monday:

The oil companies, in fact, have done very well in the decade since the spill, and until the recent price drop, and the crimp the coronavirus has put in driving, stood to do even better; the Interior Department's latest five-year plan, now on hold because of court rulings, would open nearly every square inch of America's coastal waters to new exploration.

Therein lies one of the nasty little ironies facing the friends of coastal restoration. So far, their only dependable financing model has been the revenue from the catastrophic spill, but the BP money won't last forever. One thing the state had been counting on is a steady stream of money from offshore oil leases under a 2006 revenue-sharing law passed by Congress. Which implies a robust oil industry, which in turn means more risk of offshore spills and more emissions of climate-forcing emissions from automobile tailpipes, which in turn means more sea level rise.

The bottom line, say climate advocates, is that it's time for a just transition to a renewable energy-based economy.

As Valerie Cleland and Jacob Eisenberg wrote last week at NRDC's Expert blog,

[T]here is simply no scenario in which it would be rational to expand our reliance on fossil fuels. In a climate crisis that already has the world reeling from wildfires, flooding, deadly heat waves, and destructive hurricanes, we need to shift to cleaner, safer sources of energy that will offer sustainable jobs into the future without wreaking havoc on our oceans, wildlife, and livelihoods.

"We should mark this 10-year memorial by moving away from the dirty fossil fuels of the past once and for all," they said.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

A decade after the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill unleashed roughly 200 million of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, ecological damage remains. And with lessons from the disaster clearly unlearned ten years and two administrations later, environmental groups say the need to ditch a fossil fuel-based energy system is more urgent than ever.

\u201cOn this day ten years ago, hundreds of millions gallons of oil spewed into the Gulf.\n\nToday we're joining groups in calling for a stop to the expansion of offshore drilling!\n\nIt's not an if, but a when we have the next #DeepwaterHorizon.\n\n#BP10\n\nhttps://t.co/P9yg8uhigB\u201d— Friends of the Earth (Action) (@Friends of the Earth (Action)) 1587409192

As the Associated Pressreported Monday, "black oil no longer visibly stains the beaches and estuaries" along the Gulf, but that clean image betrays a bevy of problems in and out of the waters.

"We will see environmental impacts from this for the rest of our lifetimes," Steven A. Murawski, who was chief scientist of the National Marine Fisheries Service when the Macondo well blew, told AP.

CNNdrew attention Monday to some of those consequences, pointing to research showing oil pollution in thousands of fish in the Gulf in the years following the disaster.

The research was carried out between 2011 and 2018, sampling more than 2,500 individual fish that belonged to 91 species living in 359 different locations in the Gulf. All of them contained oil exposure. [...]

The oil pollution in the fish included levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, known as PAHs. The toxic crude oil component was found in the bile of the fish. Fish bile, found in their livers, stores waste and aids digestion. [...]

While high levels of PAHs were expected in tilefish, which live in seafloor burrows where oil and PAHs are still found, the levels have been increasing over time.

The ecological impacts, both from the oil and the unprecedented use of "dispersants," were a major focus of a report out last week from Oceana, which included this summary of the deadly impacts to sea life:

"The fact that you don't see it on the beaches, or you don't see it floating around ... doesn't mean that it's gone," Clifton Nunnally, a research scientist with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, told Oceana about the oil from the 2010 spill. "It means that it's moved to a new ecosystem. And it's a system that operates on the order of millennia, not just years or decades. So, the recovery for a deep-sea ecosystem like this could be a longterm process."

Despite those impacts, as well as ongoing harm to local communities, it appears nothing has been learned. The chance of a similar oil disaster happening is just as likely now as it was 10 years ago, said Oceana.

The offshore oil drilling industry says it's put measures in place to make sure that can't happen--a claim critics like Oceana reject.

Among the problems the green groups point to as exacerbating the danger of another major spill is the Trump administration's move last May gutting offshore drilling regulations aimed at preventing a Deepwater Horizon-style disaster, including a weakening of a measure to prevent a well blowout.

And it's not just advocacy groups sounding alarm. As the New York Timesreported Monday,

[A]ll seven members of the bipartisan national commission set up to find the roots of the disaster and prevent a repeat said many of their recommendations were never taken seriously. As drilling moves farther offshore and deeper underwater, they said, another spill of equally disastrous proportions is possible.

"Offshore drilling is still as dirty and dangerous as it was 10 years ago," Diane Hoskins, Oceana campaign director, said in a statement last week.

Contributing to such fears is the Trump administration's rejection of science, deregulatory agenda, and push for increased fossil fuel extraction.

"Instead of learning lessons from the BP disaster, President Trump is proposing to radically expand offshore drilling, while dismantling the few protections put in place as a result of the catastrophic blowout," added Hoskins.

That adds up to a pretty good decade for the offshore industry. The New York Times editorial board wrote Monday:

The oil companies, in fact, have done very well in the decade since the spill, and until the recent price drop, and the crimp the coronavirus has put in driving, stood to do even better; the Interior Department's latest five-year plan, now on hold because of court rulings, would open nearly every square inch of America's coastal waters to new exploration.

Therein lies one of the nasty little ironies facing the friends of coastal restoration. So far, their only dependable financing model has been the revenue from the catastrophic spill, but the BP money won't last forever. One thing the state had been counting on is a steady stream of money from offshore oil leases under a 2006 revenue-sharing law passed by Congress. Which implies a robust oil industry, which in turn means more risk of offshore spills and more emissions of climate-forcing emissions from automobile tailpipes, which in turn means more sea level rise.

The bottom line, say climate advocates, is that it's time for a just transition to a renewable energy-based economy.

As Valerie Cleland and Jacob Eisenberg wrote last week at NRDC's Expert blog,

[T]here is simply no scenario in which it would be rational to expand our reliance on fossil fuels. In a climate crisis that already has the world reeling from wildfires, flooding, deadly heat waves, and destructive hurricanes, we need to shift to cleaner, safer sources of energy that will offer sustainable jobs into the future without wreaking havoc on our oceans, wildlife, and livelihoods.

"We should mark this 10-year memorial by moving away from the dirty fossil fuels of the past once and for all," they said.

A decade after the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill unleashed roughly 200 million of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, ecological damage remains. And with lessons from the disaster clearly unlearned ten years and two administrations later, environmental groups say the need to ditch a fossil fuel-based energy system is more urgent than ever.

\u201cOn this day ten years ago, hundreds of millions gallons of oil spewed into the Gulf.\n\nToday we're joining groups in calling for a stop to the expansion of offshore drilling!\n\nIt's not an if, but a when we have the next #DeepwaterHorizon.\n\n#BP10\n\nhttps://t.co/P9yg8uhigB\u201d— Friends of the Earth (Action) (@Friends of the Earth (Action)) 1587409192

As the Associated Pressreported Monday, "black oil no longer visibly stains the beaches and estuaries" along the Gulf, but that clean image betrays a bevy of problems in and out of the waters.

"We will see environmental impacts from this for the rest of our lifetimes," Steven A. Murawski, who was chief scientist of the National Marine Fisheries Service when the Macondo well blew, told AP.

CNNdrew attention Monday to some of those consequences, pointing to research showing oil pollution in thousands of fish in the Gulf in the years following the disaster.

The research was carried out between 2011 and 2018, sampling more than 2,500 individual fish that belonged to 91 species living in 359 different locations in the Gulf. All of them contained oil exposure. [...]

The oil pollution in the fish included levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, known as PAHs. The toxic crude oil component was found in the bile of the fish. Fish bile, found in their livers, stores waste and aids digestion. [...]

While high levels of PAHs were expected in tilefish, which live in seafloor burrows where oil and PAHs are still found, the levels have been increasing over time.

The ecological impacts, both from the oil and the unprecedented use of "dispersants," were a major focus of a report out last week from Oceana, which included this summary of the deadly impacts to sea life:

"The fact that you don't see it on the beaches, or you don't see it floating around ... doesn't mean that it's gone," Clifton Nunnally, a research scientist with the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, told Oceana about the oil from the 2010 spill. "It means that it's moved to a new ecosystem. And it's a system that operates on the order of millennia, not just years or decades. So, the recovery for a deep-sea ecosystem like this could be a longterm process."

Despite those impacts, as well as ongoing harm to local communities, it appears nothing has been learned. The chance of a similar oil disaster happening is just as likely now as it was 10 years ago, said Oceana.

The offshore oil drilling industry says it's put measures in place to make sure that can't happen--a claim critics like Oceana reject.

Among the problems the green groups point to as exacerbating the danger of another major spill is the Trump administration's move last May gutting offshore drilling regulations aimed at preventing a Deepwater Horizon-style disaster, including a weakening of a measure to prevent a well blowout.

And it's not just advocacy groups sounding alarm. As the New York Timesreported Monday,

[A]ll seven members of the bipartisan national commission set up to find the roots of the disaster and prevent a repeat said many of their recommendations were never taken seriously. As drilling moves farther offshore and deeper underwater, they said, another spill of equally disastrous proportions is possible.

"Offshore drilling is still as dirty and dangerous as it was 10 years ago," Diane Hoskins, Oceana campaign director, said in a statement last week.

Contributing to such fears is the Trump administration's rejection of science, deregulatory agenda, and push for increased fossil fuel extraction.

"Instead of learning lessons from the BP disaster, President Trump is proposing to radically expand offshore drilling, while dismantling the few protections put in place as a result of the catastrophic blowout," added Hoskins.

That adds up to a pretty good decade for the offshore industry. The New York Times editorial board wrote Monday:

The oil companies, in fact, have done very well in the decade since the spill, and until the recent price drop, and the crimp the coronavirus has put in driving, stood to do even better; the Interior Department's latest five-year plan, now on hold because of court rulings, would open nearly every square inch of America's coastal waters to new exploration.

Therein lies one of the nasty little ironies facing the friends of coastal restoration. So far, their only dependable financing model has been the revenue from the catastrophic spill, but the BP money won't last forever. One thing the state had been counting on is a steady stream of money from offshore oil leases under a 2006 revenue-sharing law passed by Congress. Which implies a robust oil industry, which in turn means more risk of offshore spills and more emissions of climate-forcing emissions from automobile tailpipes, which in turn means more sea level rise.

The bottom line, say climate advocates, is that it's time for a just transition to a renewable energy-based economy.

As Valerie Cleland and Jacob Eisenberg wrote last week at NRDC's Expert blog,

[T]here is simply no scenario in which it would be rational to expand our reliance on fossil fuels. In a climate crisis that already has the world reeling from wildfires, flooding, deadly heat waves, and destructive hurricanes, we need to shift to cleaner, safer sources of energy that will offer sustainable jobs into the future without wreaking havoc on our oceans, wildlife, and livelihoods.

"We should mark this 10-year memorial by moving away from the dirty fossil fuels of the past once and for all," they said.