SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

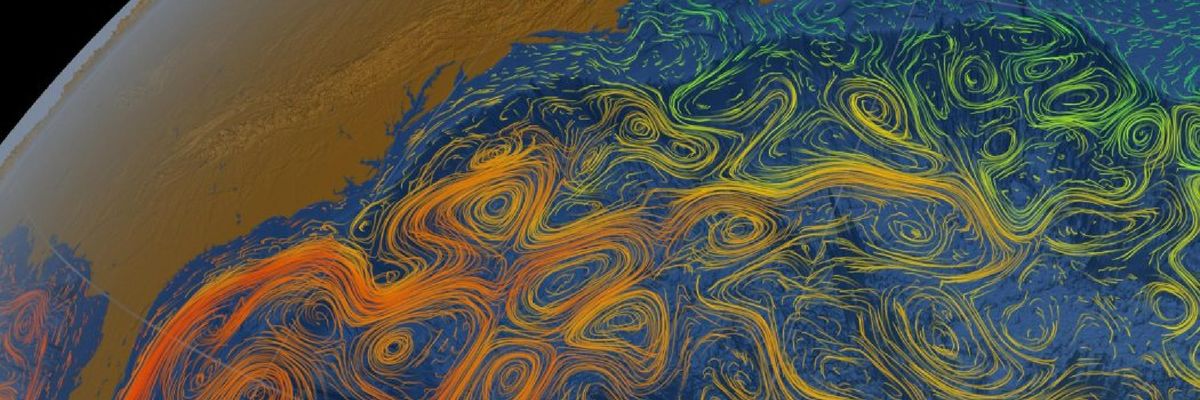

The Gulf Stream is an ocean current that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico into the Atlantic Ocean. (Image: NASA)

While heatwaves, fires, and floods produce warnings that "we are living in a climate emergency, here and now," a scientific study suggested Thursday that a crucial Atlantic Ocean current system could collapse, which "would have severe impacts on the global climate system."

"The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

--Niklas Boers, PIK

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, focuses on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream. As the United Kingdom's Met Office explains, it is "a large system of ocean currents that carry warm water from the tropics northwards into the North Atlantic," like a conveyor belt.

Previous research has shown the AMOC weakening in recent centuries. The author of the new study, Niklas Boers of the Potsdam Institute of Climate Impact Research (PIK), found that this is likely related to a loss of stability.

"The Atlantic Meridional Overturning is one of our planet's key circulation systems," Boers, who is also affiliated with universities in the U.K. and Germany, said in a statement.

"We already know from some computer simulations and from data from Earth's past, so-called paleoclimate proxy records, that the AMOC can exhibit--in addition to the currently attained strong mode--an alternative, substantially weaker mode of operation," he continued. "This bi-stability implies that abrupt transitions between the two circulation modes are in principle possible."

In the absence of long-term data on the current system's strength, Boers looked at its "fingerprints," sea-surface temperature and salinity patterns. He said that "a detailed analysis of these fingerprints in eight independent indices now suggests that the AMOC weakening during the last century is indeed likely to be associated with a loss of stability."

"The findings support the assessment that the AMOC decline is not just a fluctuation or a linear response to increasing temperatures," he continued, "but likely means the approaching of a critical threshold beyond which the circulation system could collapse."

As The Guardian's Damian Carrington reports, the collapse, "one of the planet's main potential tipping points," would be devastating on a global scale:

Such an event would have catastrophic consequences around the world, severely disrupting the rains that billions of people depend on for food in India, South America, and West Africa; increasing storms and lowering temperatures in Europe; and pushing up the sea level in the eastern U.S. It would also further endanger the Amazon rainforest and Antarctic ice sheets.

The complexity of the AMOC system and uncertainty over levels of future global heating make it impossible to forecast the date of any collapse for now. It could be within a decade or two, or several centuries away. But the colossal impact it would have means it must never be allowed to happen, the scientists said.

"The signs of destabilization being visible already is something that I wouldn't have expected and that I find scary," Boers told the newspaper. "It's something you just can't [allow to] happen."

It is unclear what level of global heating would cause a collapse, "so the only thing to do is keep emissions as low as possible," he added. "The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

Some climate action advocates responded to the study by highlighting a science fiction movie that, as famed film critic Roger Ebert wrote nearly two decades ago, "is ridiculous, yes, but sublimely ridiculous--and the special effects are stupendous."

"We all laughed at The Day After Tomorrow, back in 2004," said Guy Shrubsole, policy and campaigns coordinator at Rewilding Britain. "Turned out it was a documentary."

The environmental advocacy group 350 Tacoma responded to the findings with a call to action.

"There are warning signs that the Gulf Stream could collapse, an unimaginably catastrophic (and irreversible) impact of fossil fuel-caused climate breakdown," the group tweeted. "Scientists say we cannot allow this to happen. People in power stand in our way."

The study comes ahead of a United Nations climate summit in Glasgow set to begin October 31. Last month, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres noted the upcoming event and reminded leaders of wealthy countries that "the world urgently needs a clear and unambiguous commitment to the 1.5-degree goal of the Paris agreement," and "we are way off track."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

While heatwaves, fires, and floods produce warnings that "we are living in a climate emergency, here and now," a scientific study suggested Thursday that a crucial Atlantic Ocean current system could collapse, which "would have severe impacts on the global climate system."

"The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

--Niklas Boers, PIK

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, focuses on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream. As the United Kingdom's Met Office explains, it is "a large system of ocean currents that carry warm water from the tropics northwards into the North Atlantic," like a conveyor belt.

Previous research has shown the AMOC weakening in recent centuries. The author of the new study, Niklas Boers of the Potsdam Institute of Climate Impact Research (PIK), found that this is likely related to a loss of stability.

"The Atlantic Meridional Overturning is one of our planet's key circulation systems," Boers, who is also affiliated with universities in the U.K. and Germany, said in a statement.

"We already know from some computer simulations and from data from Earth's past, so-called paleoclimate proxy records, that the AMOC can exhibit--in addition to the currently attained strong mode--an alternative, substantially weaker mode of operation," he continued. "This bi-stability implies that abrupt transitions between the two circulation modes are in principle possible."

In the absence of long-term data on the current system's strength, Boers looked at its "fingerprints," sea-surface temperature and salinity patterns. He said that "a detailed analysis of these fingerprints in eight independent indices now suggests that the AMOC weakening during the last century is indeed likely to be associated with a loss of stability."

"The findings support the assessment that the AMOC decline is not just a fluctuation or a linear response to increasing temperatures," he continued, "but likely means the approaching of a critical threshold beyond which the circulation system could collapse."

As The Guardian's Damian Carrington reports, the collapse, "one of the planet's main potential tipping points," would be devastating on a global scale:

Such an event would have catastrophic consequences around the world, severely disrupting the rains that billions of people depend on for food in India, South America, and West Africa; increasing storms and lowering temperatures in Europe; and pushing up the sea level in the eastern U.S. It would also further endanger the Amazon rainforest and Antarctic ice sheets.

The complexity of the AMOC system and uncertainty over levels of future global heating make it impossible to forecast the date of any collapse for now. It could be within a decade or two, or several centuries away. But the colossal impact it would have means it must never be allowed to happen, the scientists said.

"The signs of destabilization being visible already is something that I wouldn't have expected and that I find scary," Boers told the newspaper. "It's something you just can't [allow to] happen."

It is unclear what level of global heating would cause a collapse, "so the only thing to do is keep emissions as low as possible," he added. "The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

Some climate action advocates responded to the study by highlighting a science fiction movie that, as famed film critic Roger Ebert wrote nearly two decades ago, "is ridiculous, yes, but sublimely ridiculous--and the special effects are stupendous."

"We all laughed at The Day After Tomorrow, back in 2004," said Guy Shrubsole, policy and campaigns coordinator at Rewilding Britain. "Turned out it was a documentary."

The environmental advocacy group 350 Tacoma responded to the findings with a call to action.

"There are warning signs that the Gulf Stream could collapse, an unimaginably catastrophic (and irreversible) impact of fossil fuel-caused climate breakdown," the group tweeted. "Scientists say we cannot allow this to happen. People in power stand in our way."

The study comes ahead of a United Nations climate summit in Glasgow set to begin October 31. Last month, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres noted the upcoming event and reminded leaders of wealthy countries that "the world urgently needs a clear and unambiguous commitment to the 1.5-degree goal of the Paris agreement," and "we are way off track."

While heatwaves, fires, and floods produce warnings that "we are living in a climate emergency, here and now," a scientific study suggested Thursday that a crucial Atlantic Ocean current system could collapse, which "would have severe impacts on the global climate system."

"The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

--Niklas Boers, PIK

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, focuses on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which includes the Gulf Stream. As the United Kingdom's Met Office explains, it is "a large system of ocean currents that carry warm water from the tropics northwards into the North Atlantic," like a conveyor belt.

Previous research has shown the AMOC weakening in recent centuries. The author of the new study, Niklas Boers of the Potsdam Institute of Climate Impact Research (PIK), found that this is likely related to a loss of stability.

"The Atlantic Meridional Overturning is one of our planet's key circulation systems," Boers, who is also affiliated with universities in the U.K. and Germany, said in a statement.

"We already know from some computer simulations and from data from Earth's past, so-called paleoclimate proxy records, that the AMOC can exhibit--in addition to the currently attained strong mode--an alternative, substantially weaker mode of operation," he continued. "This bi-stability implies that abrupt transitions between the two circulation modes are in principle possible."

In the absence of long-term data on the current system's strength, Boers looked at its "fingerprints," sea-surface temperature and salinity patterns. He said that "a detailed analysis of these fingerprints in eight independent indices now suggests that the AMOC weakening during the last century is indeed likely to be associated with a loss of stability."

"The findings support the assessment that the AMOC decline is not just a fluctuation or a linear response to increasing temperatures," he continued, "but likely means the approaching of a critical threshold beyond which the circulation system could collapse."

As The Guardian's Damian Carrington reports, the collapse, "one of the planet's main potential tipping points," would be devastating on a global scale:

Such an event would have catastrophic consequences around the world, severely disrupting the rains that billions of people depend on for food in India, South America, and West Africa; increasing storms and lowering temperatures in Europe; and pushing up the sea level in the eastern U.S. It would also further endanger the Amazon rainforest and Antarctic ice sheets.

The complexity of the AMOC system and uncertainty over levels of future global heating make it impossible to forecast the date of any collapse for now. It could be within a decade or two, or several centuries away. But the colossal impact it would have means it must never be allowed to happen, the scientists said.

"The signs of destabilization being visible already is something that I wouldn't have expected and that I find scary," Boers told the newspaper. "It's something you just can't [allow to] happen."

It is unclear what level of global heating would cause a collapse, "so the only thing to do is keep emissions as low as possible," he added. "The likelihood of this extremely high-impact event happening increases with every gram of CO2 that we put into the atmosphere."

Some climate action advocates responded to the study by highlighting a science fiction movie that, as famed film critic Roger Ebert wrote nearly two decades ago, "is ridiculous, yes, but sublimely ridiculous--and the special effects are stupendous."

"We all laughed at The Day After Tomorrow, back in 2004," said Guy Shrubsole, policy and campaigns coordinator at Rewilding Britain. "Turned out it was a documentary."

The environmental advocacy group 350 Tacoma responded to the findings with a call to action.

"There are warning signs that the Gulf Stream could collapse, an unimaginably catastrophic (and irreversible) impact of fossil fuel-caused climate breakdown," the group tweeted. "Scientists say we cannot allow this to happen. People in power stand in our way."

The study comes ahead of a United Nations climate summit in Glasgow set to begin October 31. Last month, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres noted the upcoming event and reminded leaders of wealthy countries that "the world urgently needs a clear and unambiguous commitment to the 1.5-degree goal of the Paris agreement," and "we are way off track."