U.S.-trained Somali troops stand at attention during a graduation ceremony. (Photo: U.S. Africa Command)

New Analysis Reveals Why Repealing 2001 AUMF 'Will Not Be Enough to Kill the War on Terror'

As the executive branch's power to authorize military activities has metastasized under four administrations since 9/11, oversight of "counterterrorism operations" across the globe has crumbled.

A new analysis published Tuesday by the Costs of War Project details how the power of U.S. presidents to greenlight military activities has grown since the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force was first enacted, demonstrating why simply repealing the measure now won't be enough to end so-called "counterterrorism operations" across the globe.

"The AUMF... is the beginning of the story, not the end."

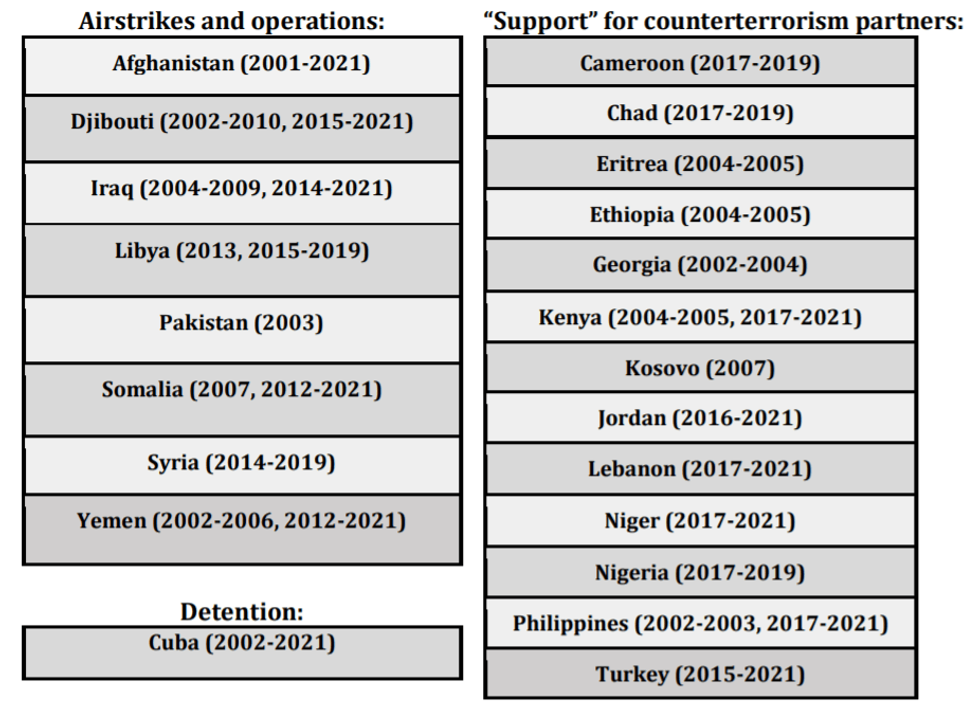

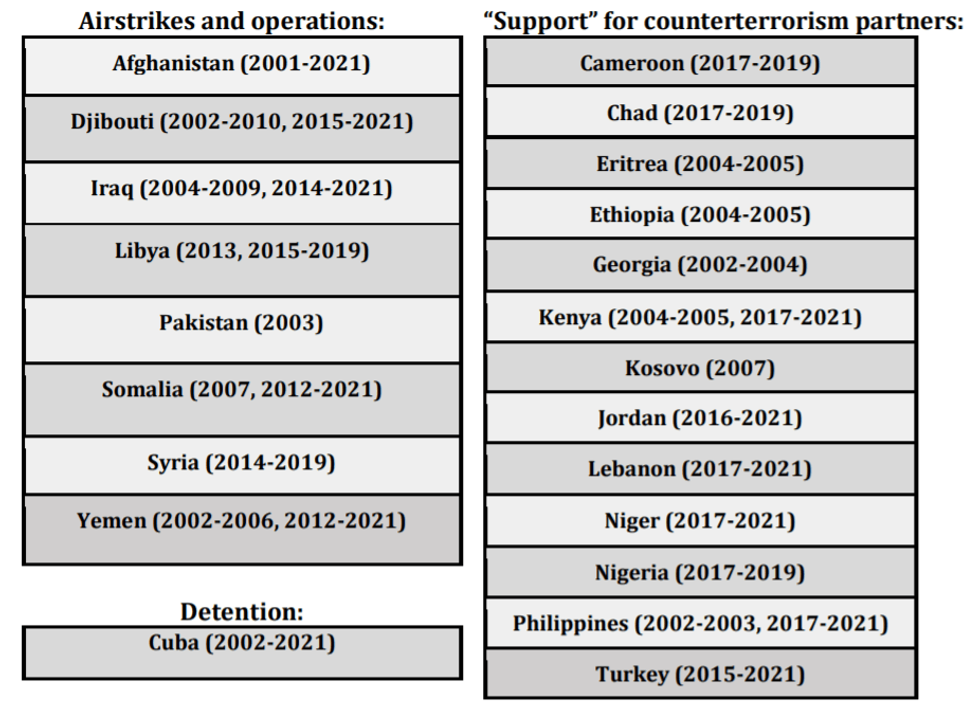

Drawing on Congressional Research Service data updated through August 6, the report documents where and how the 2001 AUMF has been used--and also highlights how counterterrorism operations have taken place in dozens of additional nations without the aid of the law that launched the so-called "War on Terror" just one week after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

"In light of our previous research showing how widespread U.S. counterterrorism activities are globally, this analysis shows where the 2001 AUMF has been used and when and where counterterrorism operations have happened outside the umbrella of the AUMF," report author Stephanie Savell, co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University's Watson Institute, said in a statement.

"There are several cases of combat and airstrikes since 2001 that various presidents have not reported to Congress," added Savell.

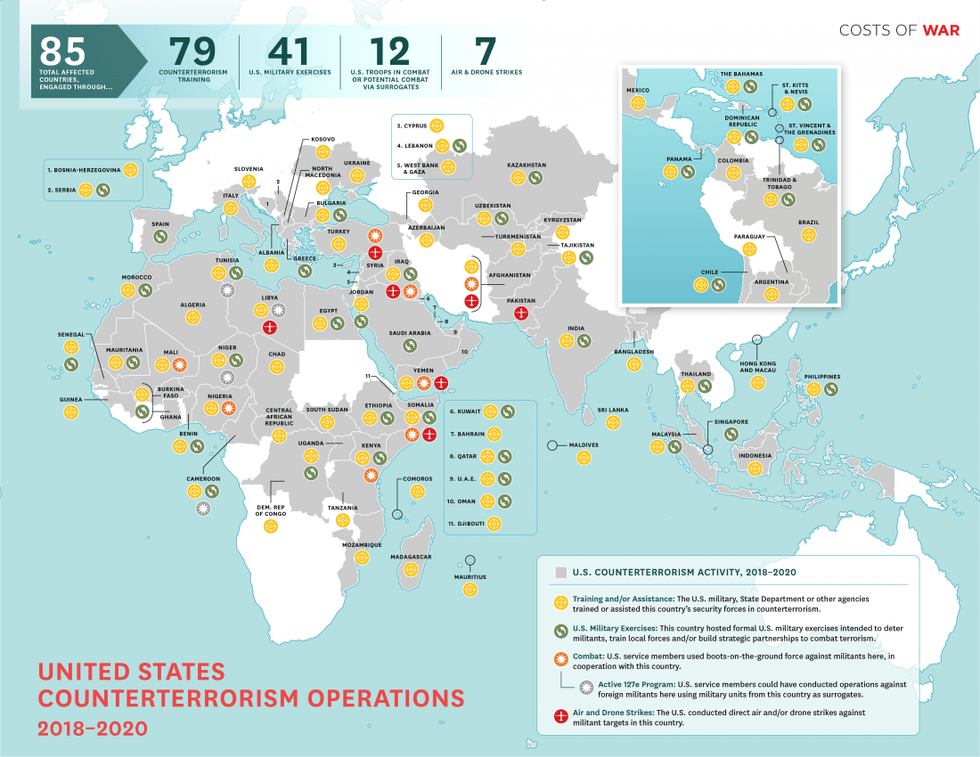

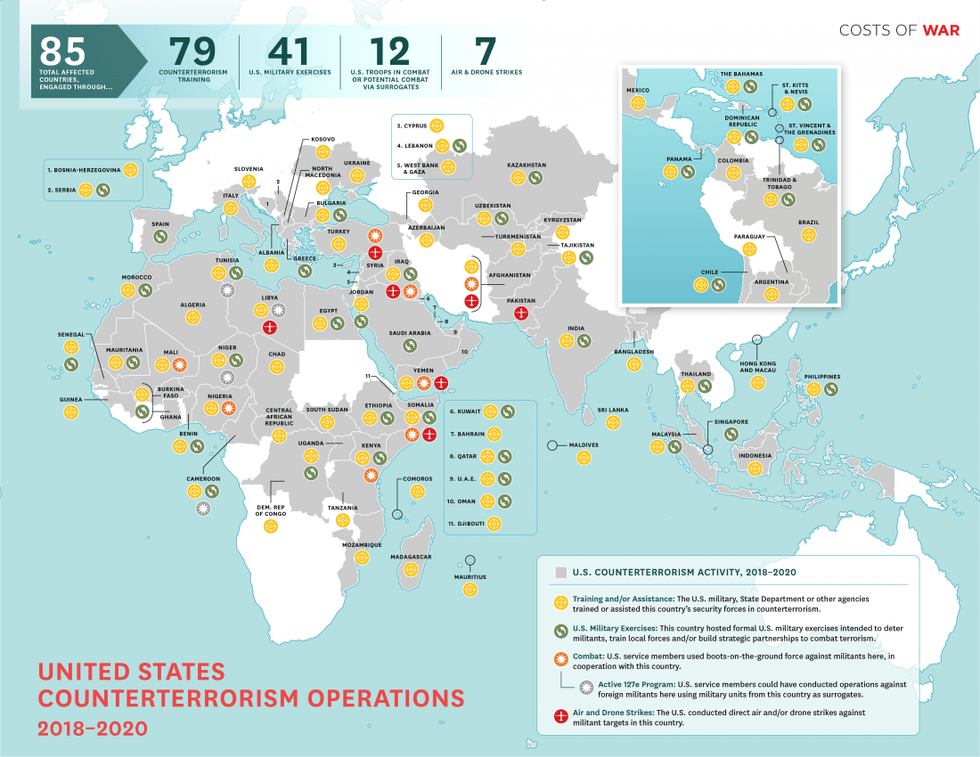

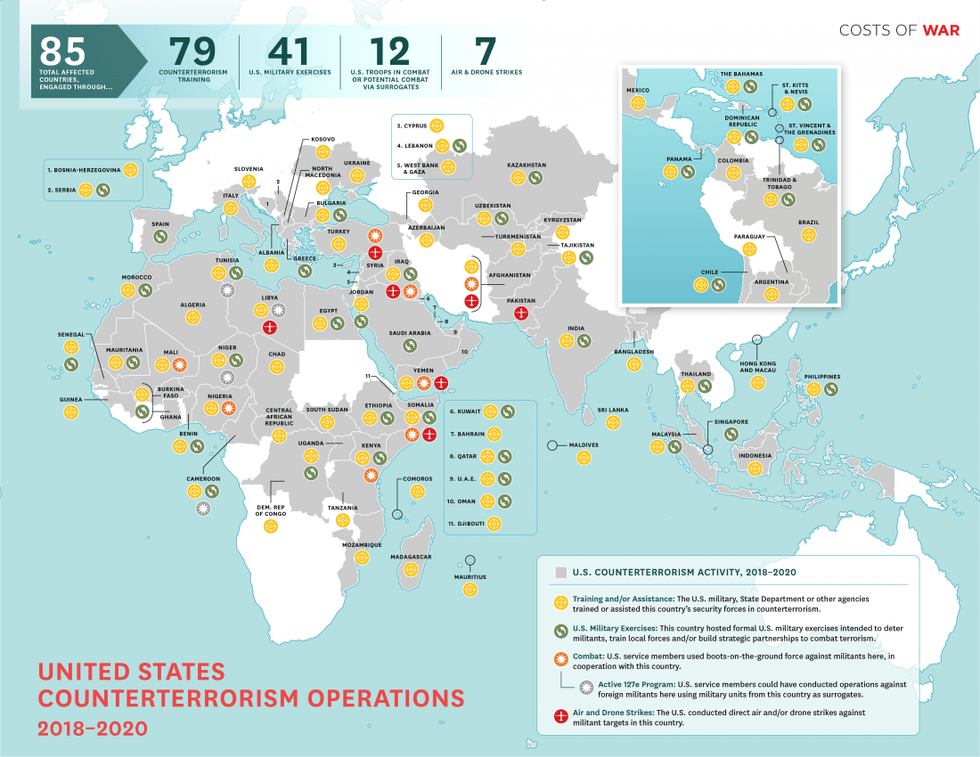

Earlier this year, Savell found that the U.S. engaged in counterterrorism activities--which range from airstrikes to "training" foreign troops to full-blown occupations--in a whopping 85 countries from 2018 to 2020 alone.

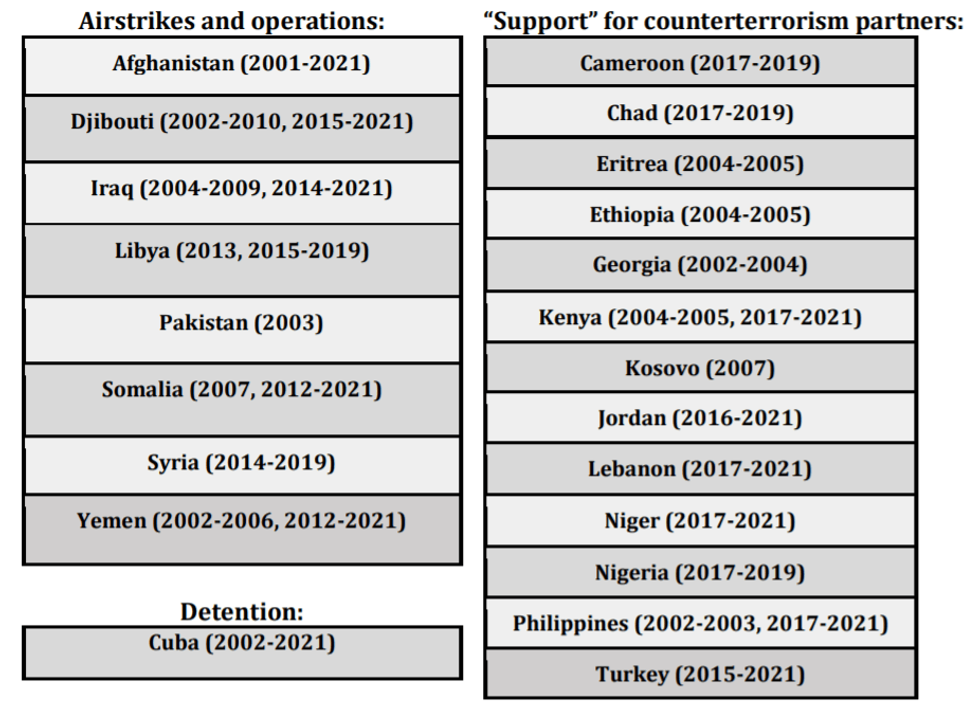

Over the course of two decades, however, former Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, as well as current President Joe Biden, have collectively cited the 2001 AUMF to justify counterterrorism operations in 22 countries.

Notably, the precise number of military activities that have occurred within those 22 countries is "unknown" because "in many cases the executive branch inadequately described the full scope of U.S. actions," wrote Savell.

Furthermore, "much of the executive branch's reporting lacks geographic specificity," she pointed out. "The 2001 AUMF has often been used to justify operations in regions rather than countries."

The report notes that under the 2001 AUMF, which remains in effect today, "Congress relinquished its constitutionally assigned war powers in the fight against 'terrorism,' ceding to the president its responsibility to decide whether, when, and where the United States chooses war."

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities."

Although the president is required by the 1973 War Powers Resolution to inform Congress within 48 hours whenever U.S. troops are involved in "hostilities" or "imminent hostilities," Savell wrote that "the executive branch has consistently used vague language to describe the locations of operations, failed to accurately describe the full scope of activities in many places, and in some cases simply failed to report on counterterrorism hostilities."

The White House has failed to invoke the 2001 AUMF in multiple instances where evidence of hostilities--including U.S. airstrikes and involvement in combat--are evident, the new report shows, revealing the extent to which such nefarious activities are being carried out under other forms of legal authority that have emerged during the War on Terror.

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities and assure that there is adequate congressional oversight," said Savell.

The report takes a specific look at operations in Mail and Tunisia, where "the U.S. has conducted airstrikes and/or been involved in combat with militants, but the executive branch has not reported on these actions to Congress and failed to cite the 2001 AUMF." Instead, U.S. military involvement there has been authorized under 127(e) programs.

Savell explained:

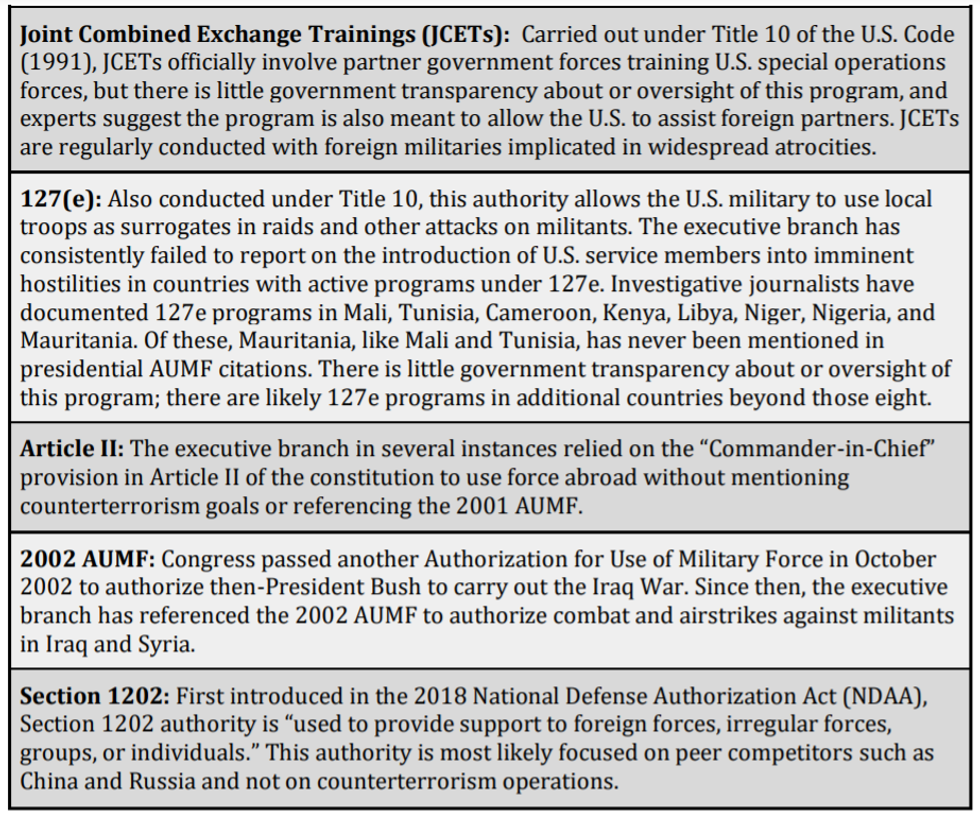

Mali and Tunisia, along with other countries, are locations of authorized 127(e) programs. The executive branch has consistently failed to report on the introduction of U.S. service members into imminent hostilities in countries with active programs under 127(e), a U.S. legal authority that allows special operations forces to plan and control missions, remaining in charge of rather than at the side of the African counterparts they are ostensibly advising and assisting. In other words, rather than U.S. forces assisting these foreign military units with their own counterterror objectives, U.S. service members use them as surrogates: they lead these units, determine their goals, and participate in their raids against people they suspect of terrorist activity. Unofficially, U.S. officials have admitted that 'If you're deployed under this combating terrorism authority, 127(e), that's probably combat.'"

In addition to Mali and Tunisia, investigative journalists have also documented 127(e) programs in Cameroon, Kenya, Libya, Niger, Nigeria, and Mauritania. Of these, Mauritania, like Mali and Tunisia, has never been cited in reference to the 2001 AUMF. While it is unclear when the 127(e) program began in Mauritania, that country has since ended its partnership in the program, which was "longstanding." According to retired Brig. Gen. Donald Bolduc, commander of numerous U.S. special operations forces in Africa through June 2017, "The host country has to understand what they signed up for, and Mauritania was never comfortable with what they signed up for. It just didn't fit how they saw themselves, giving up authority over one of their units."

Even when the executive branch reported on "support for counterterrorism (CT) operations," Savell pointed out, there were several cases in which the president "did not acknowledge that troops were or could be involved in hostilities with militants."

For example, in Niger in 2017, four U.S. service members were killed in an ambush as they attempted to carry out a raid on a militant compound, but President Trump cited the AUMF only after this incident came to light. Another example is the citation of "support" for CT operations in Kenya but failure to acknowledge a combat incident in January 2020, when Al Shabaab militants attacked a U.S. military base in Manda Bay and killed three Americans, including one Army soldier and two Pentagon contractors. U.S. forces engaged in counterfire and killed five Al Shabaab attackers

"Some experts have argued that the executive branch's failure to adequately warn Congress that the U.S. could be 'sliding towards conflict in a number of African countries' is a failure of the executive branch to comply with the War Powers Resolution," Savell added.

"Repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."

Journalist Spencer Ackerman, who first reported on the new Costs of War analysis, wrote Tuesday that "one of the legacies of the ongoing War on Terror is it that it provided the U.S. military with its first enduring footprint on the African continent."

"As an aside," he added, drawing attention to countries in and beyond Africa, "look at the commencement dates of those operations in Chad, Kenya, Lebanon, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Philippines and remember the bullshit that MAGA is trying to sell you about Donald Trump not starting any new wars."

Praising the new report, Ackerman wrote that critical "observers have long understood the AUMF as an open-ended grant of lethal, carceral, surveillance, and other military authorities stemming from 9/11. It functions as an Emergency Law, and the U.S. immediately understands such things when, say, Egypt undertakes them."

"But the AUMF, Savell's research underscores, is the beginning of the story, not the end," Ackerman stressed. "For the War on Terror has lasted sufficiently long for the AUMF to have bastard children."

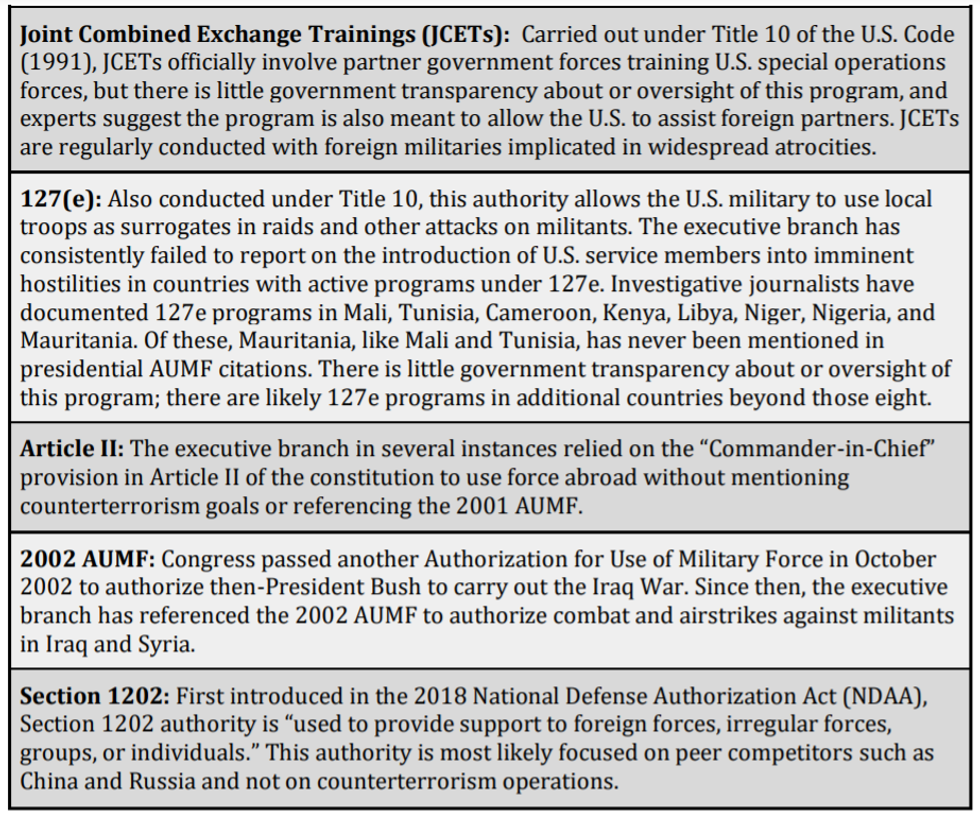

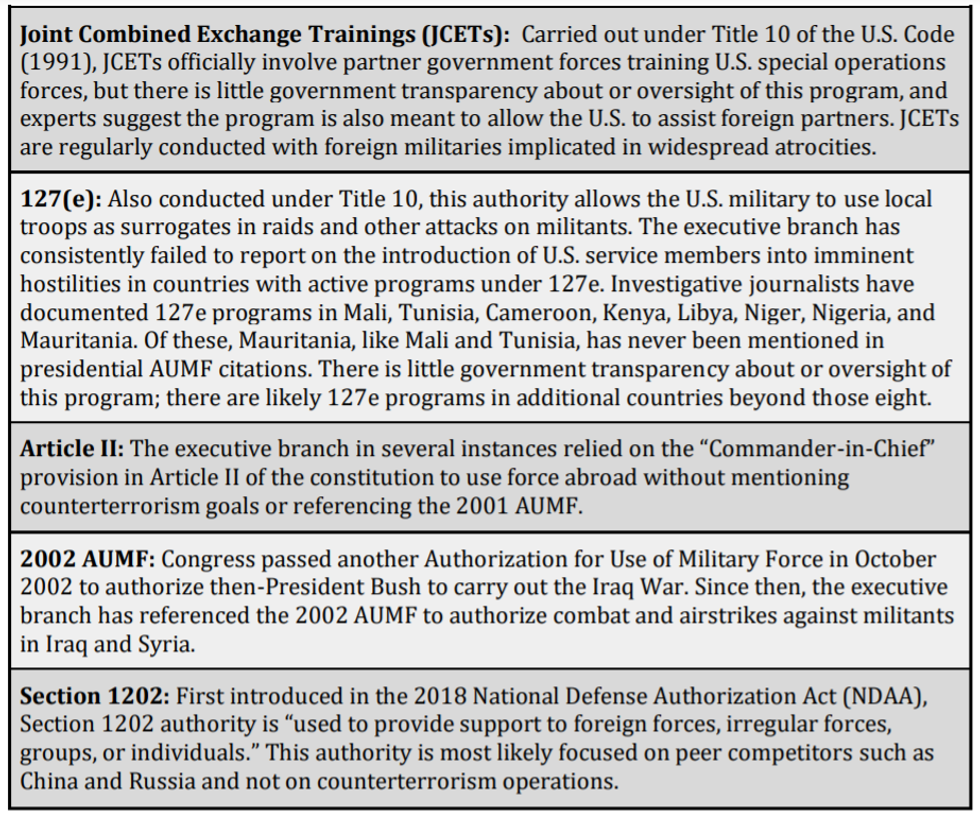

According to Savell, other authorities that presidents have cited to justify military operations include Joint Combined Exchange Trainings, 127(e), Article II of the U.S. Constitution, the 2002 AUMF, and Section 1202.

In the words of Ackerman, "Savell's research reminds us how little we will know about what unfolds after the AUMF blesses a conflict, when it blesses a conflict at all."

Furthermore, he added, the new analysis "underscores that repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

A new analysis published Tuesday by the Costs of War Project details how the power of U.S. presidents to greenlight military activities has grown since the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force was first enacted, demonstrating why simply repealing the measure now won't be enough to end so-called "counterterrorism operations" across the globe.

"The AUMF... is the beginning of the story, not the end."

Drawing on Congressional Research Service data updated through August 6, the report documents where and how the 2001 AUMF has been used--and also highlights how counterterrorism operations have taken place in dozens of additional nations without the aid of the law that launched the so-called "War on Terror" just one week after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

"In light of our previous research showing how widespread U.S. counterterrorism activities are globally, this analysis shows where the 2001 AUMF has been used and when and where counterterrorism operations have happened outside the umbrella of the AUMF," report author Stephanie Savell, co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University's Watson Institute, said in a statement.

"There are several cases of combat and airstrikes since 2001 that various presidents have not reported to Congress," added Savell.

Earlier this year, Savell found that the U.S. engaged in counterterrorism activities--which range from airstrikes to "training" foreign troops to full-blown occupations--in a whopping 85 countries from 2018 to 2020 alone.

Over the course of two decades, however, former Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, as well as current President Joe Biden, have collectively cited the 2001 AUMF to justify counterterrorism operations in 22 countries.

Notably, the precise number of military activities that have occurred within those 22 countries is "unknown" because "in many cases the executive branch inadequately described the full scope of U.S. actions," wrote Savell.

Furthermore, "much of the executive branch's reporting lacks geographic specificity," she pointed out. "The 2001 AUMF has often been used to justify operations in regions rather than countries."

The report notes that under the 2001 AUMF, which remains in effect today, "Congress relinquished its constitutionally assigned war powers in the fight against 'terrorism,' ceding to the president its responsibility to decide whether, when, and where the United States chooses war."

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities."

Although the president is required by the 1973 War Powers Resolution to inform Congress within 48 hours whenever U.S. troops are involved in "hostilities" or "imminent hostilities," Savell wrote that "the executive branch has consistently used vague language to describe the locations of operations, failed to accurately describe the full scope of activities in many places, and in some cases simply failed to report on counterterrorism hostilities."

The White House has failed to invoke the 2001 AUMF in multiple instances where evidence of hostilities--including U.S. airstrikes and involvement in combat--are evident, the new report shows, revealing the extent to which such nefarious activities are being carried out under other forms of legal authority that have emerged during the War on Terror.

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities and assure that there is adequate congressional oversight," said Savell.

The report takes a specific look at operations in Mail and Tunisia, where "the U.S. has conducted airstrikes and/or been involved in combat with militants, but the executive branch has not reported on these actions to Congress and failed to cite the 2001 AUMF." Instead, U.S. military involvement there has been authorized under 127(e) programs.

Savell explained:

Mali and Tunisia, along with other countries, are locations of authorized 127(e) programs. The executive branch has consistently failed to report on the introduction of U.S. service members into imminent hostilities in countries with active programs under 127(e), a U.S. legal authority that allows special operations forces to plan and control missions, remaining in charge of rather than at the side of the African counterparts they are ostensibly advising and assisting. In other words, rather than U.S. forces assisting these foreign military units with their own counterterror objectives, U.S. service members use them as surrogates: they lead these units, determine their goals, and participate in their raids against people they suspect of terrorist activity. Unofficially, U.S. officials have admitted that 'If you're deployed under this combating terrorism authority, 127(e), that's probably combat.'"

In addition to Mali and Tunisia, investigative journalists have also documented 127(e) programs in Cameroon, Kenya, Libya, Niger, Nigeria, and Mauritania. Of these, Mauritania, like Mali and Tunisia, has never been cited in reference to the 2001 AUMF. While it is unclear when the 127(e) program began in Mauritania, that country has since ended its partnership in the program, which was "longstanding." According to retired Brig. Gen. Donald Bolduc, commander of numerous U.S. special operations forces in Africa through June 2017, "The host country has to understand what they signed up for, and Mauritania was never comfortable with what they signed up for. It just didn't fit how they saw themselves, giving up authority over one of their units."

Even when the executive branch reported on "support for counterterrorism (CT) operations," Savell pointed out, there were several cases in which the president "did not acknowledge that troops were or could be involved in hostilities with militants."

For example, in Niger in 2017, four U.S. service members were killed in an ambush as they attempted to carry out a raid on a militant compound, but President Trump cited the AUMF only after this incident came to light. Another example is the citation of "support" for CT operations in Kenya but failure to acknowledge a combat incident in January 2020, when Al Shabaab militants attacked a U.S. military base in Manda Bay and killed three Americans, including one Army soldier and two Pentagon contractors. U.S. forces engaged in counterfire and killed five Al Shabaab attackers

"Some experts have argued that the executive branch's failure to adequately warn Congress that the U.S. could be 'sliding towards conflict in a number of African countries' is a failure of the executive branch to comply with the War Powers Resolution," Savell added.

"Repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."

Journalist Spencer Ackerman, who first reported on the new Costs of War analysis, wrote Tuesday that "one of the legacies of the ongoing War on Terror is it that it provided the U.S. military with its first enduring footprint on the African continent."

"As an aside," he added, drawing attention to countries in and beyond Africa, "look at the commencement dates of those operations in Chad, Kenya, Lebanon, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Philippines and remember the bullshit that MAGA is trying to sell you about Donald Trump not starting any new wars."

Praising the new report, Ackerman wrote that critical "observers have long understood the AUMF as an open-ended grant of lethal, carceral, surveillance, and other military authorities stemming from 9/11. It functions as an Emergency Law, and the U.S. immediately understands such things when, say, Egypt undertakes them."

"But the AUMF, Savell's research underscores, is the beginning of the story, not the end," Ackerman stressed. "For the War on Terror has lasted sufficiently long for the AUMF to have bastard children."

According to Savell, other authorities that presidents have cited to justify military operations include Joint Combined Exchange Trainings, 127(e), Article II of the U.S. Constitution, the 2002 AUMF, and Section 1202.

In the words of Ackerman, "Savell's research reminds us how little we will know about what unfolds after the AUMF blesses a conflict, when it blesses a conflict at all."

Furthermore, he added, the new analysis "underscores that repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."

A new analysis published Tuesday by the Costs of War Project details how the power of U.S. presidents to greenlight military activities has grown since the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force was first enacted, demonstrating why simply repealing the measure now won't be enough to end so-called "counterterrorism operations" across the globe.

"The AUMF... is the beginning of the story, not the end."

Drawing on Congressional Research Service data updated through August 6, the report documents where and how the 2001 AUMF has been used--and also highlights how counterterrorism operations have taken place in dozens of additional nations without the aid of the law that launched the so-called "War on Terror" just one week after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

"In light of our previous research showing how widespread U.S. counterterrorism activities are globally, this analysis shows where the 2001 AUMF has been used and when and where counterterrorism operations have happened outside the umbrella of the AUMF," report author Stephanie Savell, co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University's Watson Institute, said in a statement.

"There are several cases of combat and airstrikes since 2001 that various presidents have not reported to Congress," added Savell.

Earlier this year, Savell found that the U.S. engaged in counterterrorism activities--which range from airstrikes to "training" foreign troops to full-blown occupations--in a whopping 85 countries from 2018 to 2020 alone.

Over the course of two decades, however, former Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, as well as current President Joe Biden, have collectively cited the 2001 AUMF to justify counterterrorism operations in 22 countries.

Notably, the precise number of military activities that have occurred within those 22 countries is "unknown" because "in many cases the executive branch inadequately described the full scope of U.S. actions," wrote Savell.

Furthermore, "much of the executive branch's reporting lacks geographic specificity," she pointed out. "The 2001 AUMF has often been used to justify operations in regions rather than countries."

The report notes that under the 2001 AUMF, which remains in effect today, "Congress relinquished its constitutionally assigned war powers in the fight against 'terrorism,' ceding to the president its responsibility to decide whether, when, and where the United States chooses war."

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities."

Although the president is required by the 1973 War Powers Resolution to inform Congress within 48 hours whenever U.S. troops are involved in "hostilities" or "imminent hostilities," Savell wrote that "the executive branch has consistently used vague language to describe the locations of operations, failed to accurately describe the full scope of activities in many places, and in some cases simply failed to report on counterterrorism hostilities."

The White House has failed to invoke the 2001 AUMF in multiple instances where evidence of hostilities--including U.S. airstrikes and involvement in combat--are evident, the new report shows, revealing the extent to which such nefarious activities are being carried out under other forms of legal authority that have emerged during the War on Terror.

"There are a large number of U.S. counterterrorism operations, occurring under different legal umbrellas, which makes it difficult to track these activities and assure that there is adequate congressional oversight," said Savell.

The report takes a specific look at operations in Mail and Tunisia, where "the U.S. has conducted airstrikes and/or been involved in combat with militants, but the executive branch has not reported on these actions to Congress and failed to cite the 2001 AUMF." Instead, U.S. military involvement there has been authorized under 127(e) programs.

Savell explained:

Mali and Tunisia, along with other countries, are locations of authorized 127(e) programs. The executive branch has consistently failed to report on the introduction of U.S. service members into imminent hostilities in countries with active programs under 127(e), a U.S. legal authority that allows special operations forces to plan and control missions, remaining in charge of rather than at the side of the African counterparts they are ostensibly advising and assisting. In other words, rather than U.S. forces assisting these foreign military units with their own counterterror objectives, U.S. service members use them as surrogates: they lead these units, determine their goals, and participate in their raids against people they suspect of terrorist activity. Unofficially, U.S. officials have admitted that 'If you're deployed under this combating terrorism authority, 127(e), that's probably combat.'"

In addition to Mali and Tunisia, investigative journalists have also documented 127(e) programs in Cameroon, Kenya, Libya, Niger, Nigeria, and Mauritania. Of these, Mauritania, like Mali and Tunisia, has never been cited in reference to the 2001 AUMF. While it is unclear when the 127(e) program began in Mauritania, that country has since ended its partnership in the program, which was "longstanding." According to retired Brig. Gen. Donald Bolduc, commander of numerous U.S. special operations forces in Africa through June 2017, "The host country has to understand what they signed up for, and Mauritania was never comfortable with what they signed up for. It just didn't fit how they saw themselves, giving up authority over one of their units."

Even when the executive branch reported on "support for counterterrorism (CT) operations," Savell pointed out, there were several cases in which the president "did not acknowledge that troops were or could be involved in hostilities with militants."

For example, in Niger in 2017, four U.S. service members were killed in an ambush as they attempted to carry out a raid on a militant compound, but President Trump cited the AUMF only after this incident came to light. Another example is the citation of "support" for CT operations in Kenya but failure to acknowledge a combat incident in January 2020, when Al Shabaab militants attacked a U.S. military base in Manda Bay and killed three Americans, including one Army soldier and two Pentagon contractors. U.S. forces engaged in counterfire and killed five Al Shabaab attackers

"Some experts have argued that the executive branch's failure to adequately warn Congress that the U.S. could be 'sliding towards conflict in a number of African countries' is a failure of the executive branch to comply with the War Powers Resolution," Savell added.

"Repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."

Journalist Spencer Ackerman, who first reported on the new Costs of War analysis, wrote Tuesday that "one of the legacies of the ongoing War on Terror is it that it provided the U.S. military with its first enduring footprint on the African continent."

"As an aside," he added, drawing attention to countries in and beyond Africa, "look at the commencement dates of those operations in Chad, Kenya, Lebanon, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Philippines and remember the bullshit that MAGA is trying to sell you about Donald Trump not starting any new wars."

Praising the new report, Ackerman wrote that critical "observers have long understood the AUMF as an open-ended grant of lethal, carceral, surveillance, and other military authorities stemming from 9/11. It functions as an Emergency Law, and the U.S. immediately understands such things when, say, Egypt undertakes them."

"But the AUMF, Savell's research underscores, is the beginning of the story, not the end," Ackerman stressed. "For the War on Terror has lasted sufficiently long for the AUMF to have bastard children."

According to Savell, other authorities that presidents have cited to justify military operations include Joint Combined Exchange Trainings, 127(e), Article II of the U.S. Constitution, the 2002 AUMF, and Section 1202.

In the words of Ackerman, "Savell's research reminds us how little we will know about what unfolds after the AUMF blesses a conflict, when it blesses a conflict at all."

Furthermore, he added, the new analysis "underscores that repealing the 2001 AUMF, as arduous and necessary a political task as that is, will not be enough to kill the War on Terror."