Payouts to U.S. farmers for crops destroyed by droughts and flooding surged by over 340% from 1995 to 2020, and the cost of the nation's federal crop insurance program is only expected to increase as the fossil fuel-driven climate crisis continues to exacerbate extreme weather and disrupt agriculture.

"Making changes to these programs now will be key to making U.S. agriculture more resilient to the extreme weather that lies ahead."

That's according to a new analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture released Thursday by the Environmental Working Group (EWG), which urged members of Congress to treat the upcoming Farm Bill as "a once-in-a-lifetime chance to reform federal farm policies, including crop insurance, so they encourage farmers to adapt to climate change and reduce emissions before it's too late."

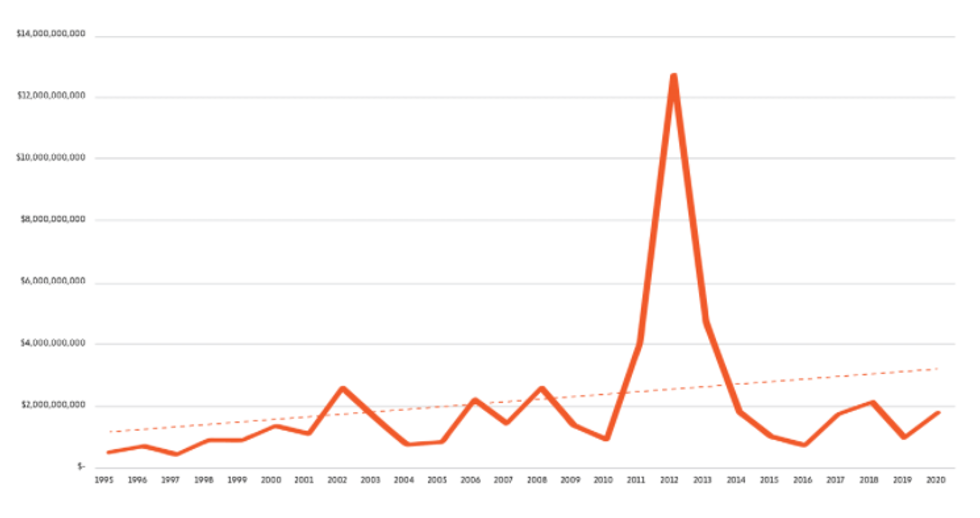

Between 1995 and 2020, farmers received a total of more than $143.5 billion in federal crop insurance payments, EWG's new database shows. Annual payouts rose significantly over that time period, from $1.6 billion in the mid-1990s to $8.5 billion in 2020--an upward trend punctuated by a 2012 peak of approximately $17.5 billion.

Most indemnity payouts during the past two-and-a-half decades covered damage from adverse weather. Just under two-thirds (61%) were made to compensate farmers for crop losses caused by too little or too much precipitation--problems, made worse by the climate emergency, that endanger food security.

Crop insurance payouts for drought were $325.6 million in 1995 and climbed to $1.6 billion in 2020--an increase of more than 400%. There was a noticeable spike in 2012, when drought indemnities hit almost $13 billion.

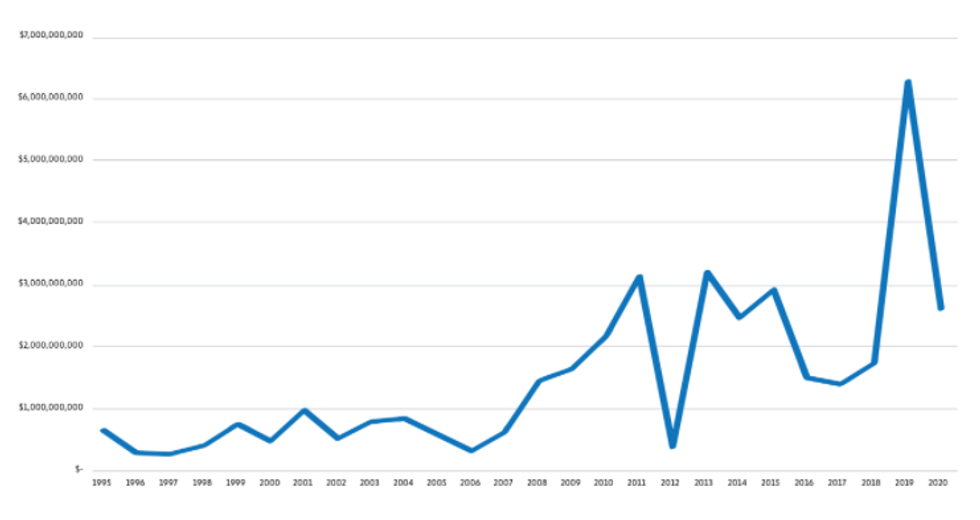

During the same time period, excess moisture indemnities grew by nearly 280%, from $685.4 million in 1995 to $2.6 billion 25 years later. In 2019 alone, farmers received roughly $6.3 billion to make up for reduced crop yields due to flooding.

Although the federal crop insurance program was first created in 1938 following the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, EWG noted that it "was not widely used by farmers until the Federal Crop Insurance Act of 1980 started subsidizing the cost of insurance policies for farmers."

Under the current arrangement, EWG explained, "farmers are almost guaranteed to make money on crop insurance policies, while taxpayers pay billions of dollars a year" for a program that is doing little to mitigate climate-related risks. The group continued:

Taxpayers pick up about 60% of premiums, which means farmers pay just 40% to get a policy.

Second, the federal government also pays private crop insurance companies for their "administrative and operating" costs, including "marketing policies, processing applications, collecting premiums, and adjusting claims," according to the Congressional Research Service.

Finally, taxpayers are liable for a significant share of the payments to producers if there is a yield or revenue loss. The private insurance companies pay farmers for losses from the premiums they receive when losses are larger than farmer-paid premiums, but taxpayers foot some of the bill for the additional payments. As losses mount, the share paid by taxpayers increases.

Legal language forces the program to be "actuarially fair"--total indemnities that are paid to farmers in the event of a loss must equal total premiums over time. But this includes premium subsidies, so total payments to farmers are much larger than the amount they pay into the program.

Insurance payouts and premium subsidies are already increasing as a result of more frequent and intense extreme weather propelled by unmitigated greenhouse gas pollution. And, EWG stressed, "these costs are expected to go up even more, as climate change causes even more unpredictable weather conditions."

According to EWG, the 10 counties with the largest crop insurance payouts for drought from 1995 to 2020 are all located in Texas, which has been growing hotter and drier for decades; scientists anticipate more of the same this century.

Brown County, South Dakota received the biggest share of flooding indemnities over the past 25 years, and nine counties in North Dakota round out the top ten. Data shows that both states have become significantly wetter since 1990.

The most recent national climate assessment warns that unless carbon dioxide and methane emissions are drastically reduced through the transformation of energy, transportation, infrastructure, and food systems, drought conditions are expected to grow worse in areas now suffering from a lack of precipitation, while extreme rainfall is likely to intensify in areas currently affected by excess moisture.

"Climate change is already hammering our communities--of every size, in every part of the country," grassroots activists at People's Action said in response to the report. "Tell the Senate that #ClimateCan'tWait!"

Even though "crop insurance is tied to climate change," EWG lamented, "the federal crop insurance program doesn't encourage or require farmers to adapt to climate change or reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It often pays farmers for the same type of loss year after year, as with multiple years of payments due to drought."

Moreover, researchers pointed out, those "astronomically high payments are in addition to $103.5 billion in subsidies that went toward farmers' crop insurance premiums."

EWG's report "did not detail average increases in premiums since 1995," Reutersnoted. "The cost of insuring crops, however, could increase between 3.5% and 22% by 2080 due to climate change, even if farmers adapted what and where they plant, according to a 2019 USDA report."

According to EWG, "making changes to these programs now will be key to making U.S. agriculture more resilient to the extreme weather that lies ahead."

The group called on congressional lawmakers, who will develop a new Farm Bill in 2023, to focus on "how to effectively fund farm programs so that farmers can adapt to and fight the climate crisis."