SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Jerry Gannaway looks over a field in which he planted cotton July 27, 2011 near Hermleigh, Texas, which officials said was facing "exceptional drought." (Photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

The megadrought which has gripped western U.S. states including California and Arizona over the past two decades has been made substantially worse by the human-caused climate crisis, new research shows, resulting in the region's driest period in about 1,200 years.

Scientists at University of California-Los Angeles, NASA, and Columbia University found that extreme heat and dryness in the West over the past two years have pushed the drought that began in 2000 past the conditions seen during a megadrought in the late 1500s.

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years."

The authors of the new study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, followed up on research they had conducted in 2020, when they found the current drought was the second-worst on record in the region after the one that lasted for several years in the 16th century.

Since that study was published, the American West has seen a heatwave so extreme it sparked dozens of wildfires and killed hundreds of people and drought conditions which affected more than 90% of the area as of last summer, pushing the region's conditions past "that extreme mark," according to the Los Angeles Times.

The scientists examined wood cores extracted from thousands of trees at about 1,600 sites across the West, using the data from growth rings in ancient trees to determine soil moisture levels going back to the 800s.

They then compared current conditions to seven other megadroughts--which are defined as droughts that are both severe and generally last a number of decades--that happened between the 800s and 1500s.

The researchers estimated that the extreme dry conditions facing tens of millions of people across the western U.S. have been made about 42% more severe by the climate crisis being driven by fossil fuel extraction and emissions.

"The results are really concerning, because it's showing that the drought conditions we are facing now are substantially worse because of climate change," Park Williams, a climate scientist at UCLA and the study's lead author, told the Los Angeles Times.

In the region Williams and his colleagues examined, the average temperature since the drought began in 2000 was 1.6deg Fahrenheit warmer than the average in the previous 50 years. Without the climate crisis driving global temperatures up, the West would still have faced drought conditions, but based on climate models studied by the researchers, there would have been a reprieve from the drought in 2005 and 2006.

"Without climate change, the past 22 years would have probably still been the driest period in 300 years," Williams said in a statement. "But it wouldn't be holding a candle to the megadroughts of the 1500s, 1200s, or 1100s."

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) said the new research must push the U.S. Congress to take far-reaching action to mitigate the climate crisis, as legislation containing measures to shift away from fossil fuel extraction and toward renewable energy is stalled largely due to objections from Republicans and right-wing Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

"It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action--before it's too late," she said.

\u201cClimate change is here and now.\n\nIf a 1,200 year mega-drought isn't enough to make people realize that, I don't know what is. It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action \u2014 before it's too late.\nhttps://t.co/jExzMKUXxr\u201d— Rep. Pramila Jayapal (@Rep. Pramila Jayapal) 1644859800

The drought has had a variety of effects on the West, including declining water supplies in the largest reservoirs of the Colorado River--Lake Mead and Lake Powell-- as well as reservoirs across California and the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, 96% of the Western U.S. is now "abnormally dry" and 88% of the region is in a drought.

"We're experiencing this variability now within this long-term aridification due to anthropogenic climate change, which is going to make the events more severe," Isla Simpson, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who was not involved in the study released Monday, told the Los Angeles Times.

The researchers also created simulations of other droughts they examined between 800 and 1500, superimposing the same amount of drying driven by climate change. In 94% of the simulations, the drought persisted for at least 23 years, and in 75% of the simulations, it lasted for at least three decades--suggesting that the current drought will continue for a number of years.

Williams said it is "extremely unlikely that this drought can be ended in one wet year."

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years," Samantha Stevenson, a climate modeler at the University of California, Santa Barbara who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The megadrought which has gripped western U.S. states including California and Arizona over the past two decades has been made substantially worse by the human-caused climate crisis, new research shows, resulting in the region's driest period in about 1,200 years.

Scientists at University of California-Los Angeles, NASA, and Columbia University found that extreme heat and dryness in the West over the past two years have pushed the drought that began in 2000 past the conditions seen during a megadrought in the late 1500s.

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years."

The authors of the new study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, followed up on research they had conducted in 2020, when they found the current drought was the second-worst on record in the region after the one that lasted for several years in the 16th century.

Since that study was published, the American West has seen a heatwave so extreme it sparked dozens of wildfires and killed hundreds of people and drought conditions which affected more than 90% of the area as of last summer, pushing the region's conditions past "that extreme mark," according to the Los Angeles Times.

The scientists examined wood cores extracted from thousands of trees at about 1,600 sites across the West, using the data from growth rings in ancient trees to determine soil moisture levels going back to the 800s.

They then compared current conditions to seven other megadroughts--which are defined as droughts that are both severe and generally last a number of decades--that happened between the 800s and 1500s.

The researchers estimated that the extreme dry conditions facing tens of millions of people across the western U.S. have been made about 42% more severe by the climate crisis being driven by fossil fuel extraction and emissions.

"The results are really concerning, because it's showing that the drought conditions we are facing now are substantially worse because of climate change," Park Williams, a climate scientist at UCLA and the study's lead author, told the Los Angeles Times.

In the region Williams and his colleagues examined, the average temperature since the drought began in 2000 was 1.6deg Fahrenheit warmer than the average in the previous 50 years. Without the climate crisis driving global temperatures up, the West would still have faced drought conditions, but based on climate models studied by the researchers, there would have been a reprieve from the drought in 2005 and 2006.

"Without climate change, the past 22 years would have probably still been the driest period in 300 years," Williams said in a statement. "But it wouldn't be holding a candle to the megadroughts of the 1500s, 1200s, or 1100s."

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) said the new research must push the U.S. Congress to take far-reaching action to mitigate the climate crisis, as legislation containing measures to shift away from fossil fuel extraction and toward renewable energy is stalled largely due to objections from Republicans and right-wing Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

"It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action--before it's too late," she said.

\u201cClimate change is here and now.\n\nIf a 1,200 year mega-drought isn't enough to make people realize that, I don't know what is. It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action \u2014 before it's too late.\nhttps://t.co/jExzMKUXxr\u201d— Rep. Pramila Jayapal (@Rep. Pramila Jayapal) 1644859800

The drought has had a variety of effects on the West, including declining water supplies in the largest reservoirs of the Colorado River--Lake Mead and Lake Powell-- as well as reservoirs across California and the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, 96% of the Western U.S. is now "abnormally dry" and 88% of the region is in a drought.

"We're experiencing this variability now within this long-term aridification due to anthropogenic climate change, which is going to make the events more severe," Isla Simpson, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who was not involved in the study released Monday, told the Los Angeles Times.

The researchers also created simulations of other droughts they examined between 800 and 1500, superimposing the same amount of drying driven by climate change. In 94% of the simulations, the drought persisted for at least 23 years, and in 75% of the simulations, it lasted for at least three decades--suggesting that the current drought will continue for a number of years.

Williams said it is "extremely unlikely that this drought can be ended in one wet year."

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years," Samantha Stevenson, a climate modeler at the University of California, Santa Barbara who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times.

The megadrought which has gripped western U.S. states including California and Arizona over the past two decades has been made substantially worse by the human-caused climate crisis, new research shows, resulting in the region's driest period in about 1,200 years.

Scientists at University of California-Los Angeles, NASA, and Columbia University found that extreme heat and dryness in the West over the past two years have pushed the drought that began in 2000 past the conditions seen during a megadrought in the late 1500s.

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years."

The authors of the new study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, followed up on research they had conducted in 2020, when they found the current drought was the second-worst on record in the region after the one that lasted for several years in the 16th century.

Since that study was published, the American West has seen a heatwave so extreme it sparked dozens of wildfires and killed hundreds of people and drought conditions which affected more than 90% of the area as of last summer, pushing the region's conditions past "that extreme mark," according to the Los Angeles Times.

The scientists examined wood cores extracted from thousands of trees at about 1,600 sites across the West, using the data from growth rings in ancient trees to determine soil moisture levels going back to the 800s.

They then compared current conditions to seven other megadroughts--which are defined as droughts that are both severe and generally last a number of decades--that happened between the 800s and 1500s.

The researchers estimated that the extreme dry conditions facing tens of millions of people across the western U.S. have been made about 42% more severe by the climate crisis being driven by fossil fuel extraction and emissions.

"The results are really concerning, because it's showing that the drought conditions we are facing now are substantially worse because of climate change," Park Williams, a climate scientist at UCLA and the study's lead author, told the Los Angeles Times.

In the region Williams and his colleagues examined, the average temperature since the drought began in 2000 was 1.6deg Fahrenheit warmer than the average in the previous 50 years. Without the climate crisis driving global temperatures up, the West would still have faced drought conditions, but based on climate models studied by the researchers, there would have been a reprieve from the drought in 2005 and 2006.

"Without climate change, the past 22 years would have probably still been the driest period in 300 years," Williams said in a statement. "But it wouldn't be holding a candle to the megadroughts of the 1500s, 1200s, or 1100s."

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) said the new research must push the U.S. Congress to take far-reaching action to mitigate the climate crisis, as legislation containing measures to shift away from fossil fuel extraction and toward renewable energy is stalled largely due to objections from Republicans and right-wing Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

"It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action--before it's too late," she said.

\u201cClimate change is here and now.\n\nIf a 1,200 year mega-drought isn't enough to make people realize that, I don't know what is. It's time for Congress to act by making meaningful investments into climate action \u2014 before it's too late.\nhttps://t.co/jExzMKUXxr\u201d— Rep. Pramila Jayapal (@Rep. Pramila Jayapal) 1644859800

The drought has had a variety of effects on the West, including declining water supplies in the largest reservoirs of the Colorado River--Lake Mead and Lake Powell-- as well as reservoirs across California and the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, 96% of the Western U.S. is now "abnormally dry" and 88% of the region is in a drought.

"We're experiencing this variability now within this long-term aridification due to anthropogenic climate change, which is going to make the events more severe," Isla Simpson, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who was not involved in the study released Monday, told the Los Angeles Times.

The researchers also created simulations of other droughts they examined between 800 and 1500, superimposing the same amount of drying driven by climate change. In 94% of the simulations, the drought persisted for at least 23 years, and in 75% of the simulations, it lasted for at least three decades--suggesting that the current drought will continue for a number of years.

Williams said it is "extremely unlikely that this drought can be ended in one wet year."

"We're sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we've seen in the last several hundred years," Samantha Stevenson, a climate modeler at the University of California, Santa Barbara who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times.

"We have been told they are looking for anti-Trump or anti-Musk language," an anonymous source said of potential surveillance at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Staff with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency fear that billionaire and presidential adviser Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency is spying on them using artificial intelligence, according to reporting from Reuters, The Guardian, and Crooked Media's newsletter What a Day.

According to Reuters reporting published Tuesday, Trump administration officials told some managers at the EPA that DOGE is rolling out AI to monitor for communications that may be perceived as hostile to U.S. President Donald Trump or Musk, citing two unnamed sources with knowledge of the situation.

According to those two sources, who relayed comments made by Trump-appointed officials in posts at the EPA, DOGE was using AI to monitor communication apps such as Microsoft Teams. "Be careful what you say, what you type, and what you do," an EPA manager said, according to one of the sources.

"We have been told they are looking for anti-Trump or anti-Musk language," a third source told Reuters.

The outlet, however, could not independently confirm whether AI was being implemented.

After the story was published, the EPA told Reuters in a statement that it was "looking at AI to better optimize agency functions and administrative efficiencies." However, the agency said it was not using AI "as it makes personnel decisions in concert with DOGE." The EPA also did not directly address whether it was using AI to snoop on employees.

In response to Reuters' reporting, the government accountability group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington wrote on X, "Let's be clear: the career civil servants who work in the government serve the American people, not Donald Trump."

According to Thursday reporting from The Guardian and Reuters, EPA managers told employees during a Wednesday morning meeting that DOGE is "using AI to scan through agency communications to find any anti-Musk, anti-Doge, or anti-Trump statements," according to an employee who was quoted anonymously.

Since returning to power, Trump has launched an all-out assault on environmental protection, including through cuts to programs and personnel at the EPA. According to The New York Times, the EPA has already undergone a 3% staff reduction so far, but the agency also plans to eliminate its scientific research arm, which would mean dismissing as many as 1,155 scientists, according to reporting from last month. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin has also said he would like to cut 65% of the agency's budget.

The Guardian and What a Day also reviewed an email from a manager at the Association of Clean Water Administrators, a group of state and interstate bodies that works with the EPA on water quality and management, which warned workers that meetings with EPA employees might be monitored by AI.

"We recently learned that all EPA phones (landline/mobile), all Teams/Zoom virtual meetings, and calendar entries are being transcribed/monitored," the email states. The recorded information is then fed into an "AI tool" which analyzes and scrutinizes what has been recorded. "I do not know if DOGE is doing the analysis or … the agency itself," according to the author of the email, per The Guardian and What a Day.

The EPA denied that it's recording meetings, but it did not address the question of an AI tool, according to the outlets.

According to The Guardian and What a Day, employees at other agencies also fear they are being surveilled. For example, a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs official warned employees that virtual meetings are being recorded in secret, according to an email reviewed by the two outlets. In February, managers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration warned some workers to be careful about what they say on calls, per an employee there.

"It's like being in a horror film where you know something out there [wants] to kill you but you never know when or how or who it is," one anonymously quoted employee from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development told The Guardian and What a Day, evoking the climate of fear that is rife among government workers.

"Is there any doubt in anyone's mind they were tipped off?" asked one progressive news outlet.

As retirees, small business owners, and consumers reeled from the chaos sparked by U.S. President Donald Trump's erratic tariff policies, the richest people on the planet saw their wealth surge Wednesday as the White House partially froze the duties it imposed on most countries.

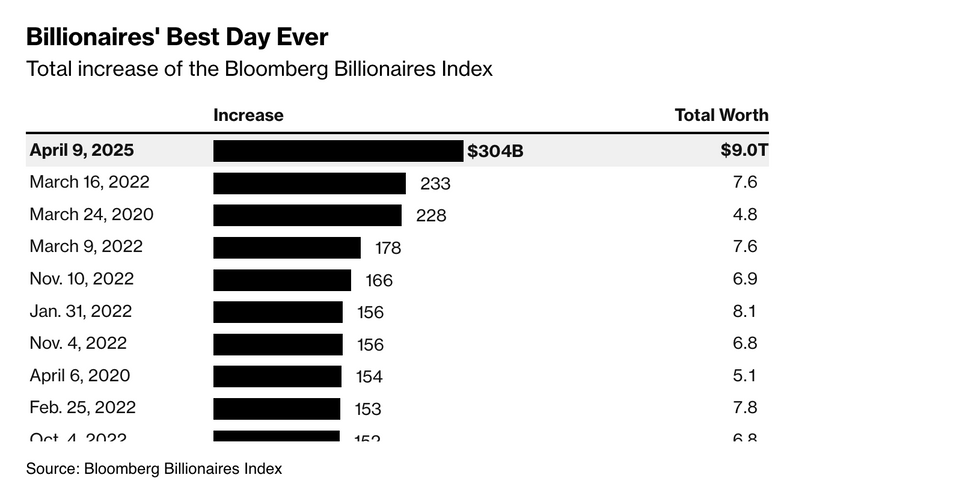

Trump's announcement of the 90-day pause sparked a historic market rally that added $304 billion to the collective wealth of the world's top billionaires, according to a Bloomberg estimate. The outlet called the jump "the largest one-day gain in the history of the Bloomberg Billionaires Index," which was launched in 2012.

"The largest individual gainer Wednesday was Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk, who added $36 billion to his fortune as the EV manufacturer's stock jumped 23%, followed by Meta Platforms Inc.'s Mark Zuckerberg, who gained almost $26 billion," Bloomberg reported. "Nvidia Corp.'s Jensen Huang saw his wealth rise $15.5 billion as the chipmaker's shares rebounded 19%, nearly offsetting its 13% decline in the week to Tuesday's close."

Though the stock market gave up some of the massive gains on Thursday amid continued uncertainty about Trump's tariffs, the rapid billionaire wealth surge amplified concerns about possible market manipulation and insider trading ahead of the president's announcement of a 90-day pause. Trump publicly encouraged people to buy stock just hours before announcing the pause.

"Is there any doubt in anyone's mind they were tipped off?" The Tennessee Holler, a progressive news outlet, wrote on social media. "They are laughing at us all."

In the days leading up to the president's partial tariff pause, some of his billionaire supporters publicly criticized his approach as their wealth took a hit amid the trade war-induced market sell-off.

According to Bloomberg, the 500 richest people in the world saw their collective wealth fall by $208 billion the day after Trump announced the sweeping tariffs last week. The Wall Street Journal reported Thursday that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent was "flooded with worried calls from Wall Street over the weekend and felt strongly he had to persuade Trump that a pause was needed."

The partial tariff pause came a day before the Republican-controlled House passed a budget blueprint that paves the way for another round of tax cuts that would primarily benefit the wealthiest Americans.

"These tariffs are not designed to solve an actual trade or economic challenge," Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the top Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, said Thursday. "They're designed to soak typical workers with higher taxes in order to help pay for handouts to the top."

"They're focused on yet more handouts to billionaires and corporations," Wyden added, "and everybody else is going to be on the hook to pay for them."

"House Republicans want to make it harder for federal courts to serve as a check on Trump's lawlessness and overreach," said one advocate. "But that's not how our democracy works."

With the Trump administration's attacks on the First Amendment, birthright citizenship, and other constitutional rights in full swing, Republicans in the U.S. House on Wednesday passed a bill that one advocacy group called a "sneak attack" on another bedrock principle of U.S. democracy.

"The passage of the No Rogue Rulings Act (NORRA) is an ideological attack on the checks and balances of our Constitution," said Celina Stewart, CEO of the League of Women Voters.

The bill, which passed 219-213, with only Rep. Mike Turner (R-Ohio) joining Democrats in opposing it, would limit U.S. District Court judges' ability to issue nationwide injunctions blocking President Donald Trump's executive orders.

The legislation was proposed by Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) after federal judges blocked several actions by Trump, including his executive order aiming to end birthright citizenship, his mass expulsion of immigrants to El Salvador's prison system, his freeze on federal grants and loans, and the so-called Department of Government Efficiency's (DOGE) mass firings of federal employees.

NORRA "brings us one step closer to dismantling our democracy for the benefit of one man and his extreme agenda that is actively harming people across the country," said Maggie Jo Buchanan, interim executive director of the judicial reform group Demand Justice. "Anyone who voted in favor of this bill failed them and our country today."

"Passage of this bill by the U.S. House is an overreach on the part of the legislative branch, and we urge the U.S. Senate to reject this legislation when it comes to the floor."

Members of the judiciary including Judges James Boasberg, Paul A. Engelmayer, and John Batestes have faced calls for impeachment over their respective rulings blocking Trump from sending planeloads of immigrants to El Salvador, barring DOGE from accessing the Treasury Department's payment system, and directing federal health agencies to restore public health data to their websites after Trump ordered them to delete it.

With impeachment votes unlikely to succeed, Stewart said the legislation proposed by Issa "is a political attempt to restrain and block our federal courts from their constitutional responsibility."

"Judges appointed to the federal bench are independent bodies that review executive and legislative actions to determine their constitutionality. This is a simple process that has been in place for centuries," said Stewart.

"The League believes that all powers of the U.S. government should be exercised within the constitutional framework to protect the balance among the three branches of government," she added. "Passage of this bill by the U.S. House is an overreach on the part of the legislative branch, and we urge the U.S. Senate to reject this legislation when it comes to the floor."

Christina Harvey, executive director of the progressive advocacy group Stand Up America, suggested that in their attacks on federal judges, Republicans are trying to weaken "the first line of defense against Donald Trump's attempts to cut essential services and attack our freedoms."

"In response to legal rulings that haven't gone Trump's way, House Republicans want to make it harder for federal courts to serve as a check on Trump's lawlessness and overreach," said Harvey. "But that's not how our democracy works. Trump is a president bound by the checks and balances of our Constitution, not a king with unlimited power."

Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) pointed to the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education to highlight the irrationality of Republicans' attempt to bar judges from applying their rulings to the entire nation.

"A nationwide injunction is a necessary part of the judicial tool kit," Raskin told NBC News. "Why should every person affected [by an issue] have to go to court? Why should millions of people have to create their own case? Why should Brown vs. Board of Education have applied to just Linda Brown as opposed to everybody affected?"

Harvey called on Senate leaders to "uphold their oath and block any attempt to weaken the federal courts."

"Anything less," she said, "would be walking away from their constitutional duties."