SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

A boy pours tap water into a drinking glass. (Photo: Teresa Short/Getty Images)

The testing method used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and local officials around the country is so circumscribed that regulators almost certainly have an incomplete understanding of the extent to which the nation's drinking water is contaminated with toxic "forever chemicals."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?"

That's according to The Guardian's analysis of water samples taken in nine cities with high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) pollution, the findings of which were published Wednesday.

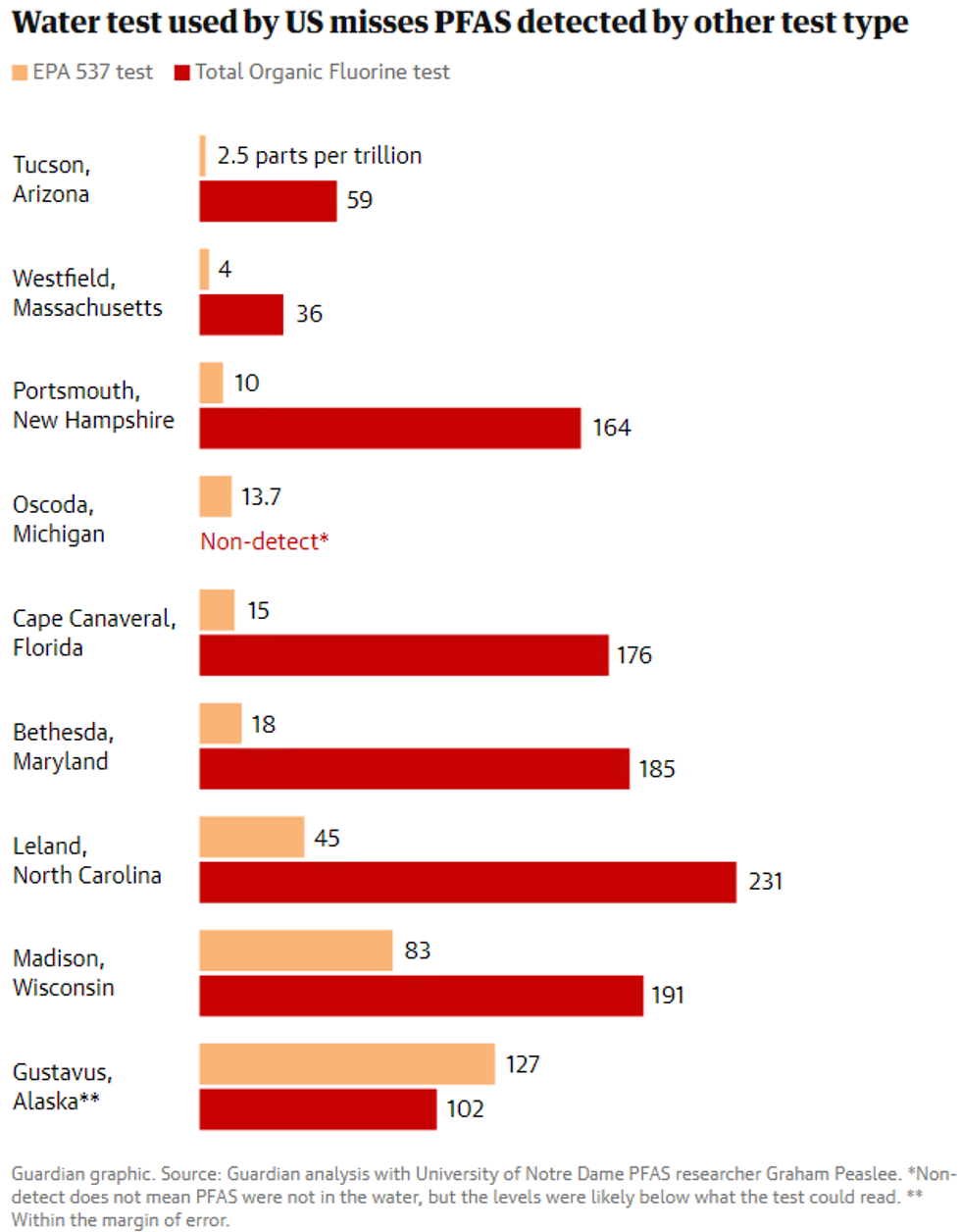

The newspaper examined water samples from the nine hot spots using two types of tests: an EPA-developed method that detects 30 types of PFAS and a more robust method that checks for a marker of the more than 9,000 PFAS compounds known to exist.

In seven of the nine cities, higher levels of PFAS were found in water samples when using a "total organic fluorine" (TOF) test that identifies markers for all known PFAS compounds than when using the EPA test--at concentrations up to 24 times greater.

"The EPA is doing the bare minimum it can and that's putting people's health at risk," said Kyla Bennett, the policy director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

PFAS are a class of synthetic compounds widely called forever chemicals because they don't fully break down--polluting people's bodies and the environment for years on end.

Scientists have linked long-term exposure to PFAS--which recent studies have identified at unsafe levels in the drinking water of more than 200 million Americans and detected in 97% of blood and 100% of breast milk samples--to numerous adverse health outcomes, including cancer, reproductive and developmental harms, immune system damage, and other negative effects.

Last month, the Biden administration unveiled what environmental groups described as "baby steps" to address toxic forever chemicals, including an allocation of $10 billion to protect drinking water from PFAS and other pollutants.

"But critics say when it comes to identifying PFAS-contaminated water, the limitations of the test used by state and federal regulators, which is called the EPA 537 method, virtually guarantees regulators will never have a full picture of contamination levels as industry churns out new compounds much faster than researchers can develop the science to measure them," The Guardian reported.

"That creates even more incentive for industry to shift away from older compounds," the newspaper noted. "If chemical companies produce newer PFAS, regulators won't be able to find the pollution."

The outlet added:

Clean water advocacy groups last year urged the EPA to use more comprehensive tests that they said would "give us a better understanding of the totality of PFAS contamination," but the agency told The Guardian it currently has no such plans.

In a statement to The Guardian, the EPA said it "continues to conduct research and monitor advances in analytical methodologies... that may improve our ability to measure more PFAS."

But that's hardly a sufficient response according to researchers such as Graham Peaslee, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who helped conduct the new analysis.

"We're looking for and studying less than 1% of PFAS so what the heck is that other 99%?" asked Peaslee. "I've never seen a good PFAS, so they're all going to have some toxicity."

Since Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974, the EPA has established maximum contaminant levels for more than 90 pollutants, but it hasn't added any new chemicals to its regulated list since 2000.

"The U.S. tap water system," the Environmental Working Group said last November after updating its national database, "is plagued by antiquated infrastructure and rampant pollution of source water, while out-of-date EPA regulations, often relying on archaic science, allow unsafe levels of toxic chemicals in drinking water."

"The EPA and industry have long argued that many newer PFAS that can't be detected are safe," The Guardian reported. "However, most new compounds have not been independently reviewed, and the types of PFAS that have been studied have been found to be toxic and persistent in the environment."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?" Bennett asked. "Why are we messing around?"

Nearly one year ago, the U.S. House passed the PFAS Action Act of 2021, which would improve federal oversight of toxic forever chemicals and facilitate clean-up efforts. The legislation has stalled in the U.S. Senate.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The testing method used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and local officials around the country is so circumscribed that regulators almost certainly have an incomplete understanding of the extent to which the nation's drinking water is contaminated with toxic "forever chemicals."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?"

That's according to The Guardian's analysis of water samples taken in nine cities with high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) pollution, the findings of which were published Wednesday.

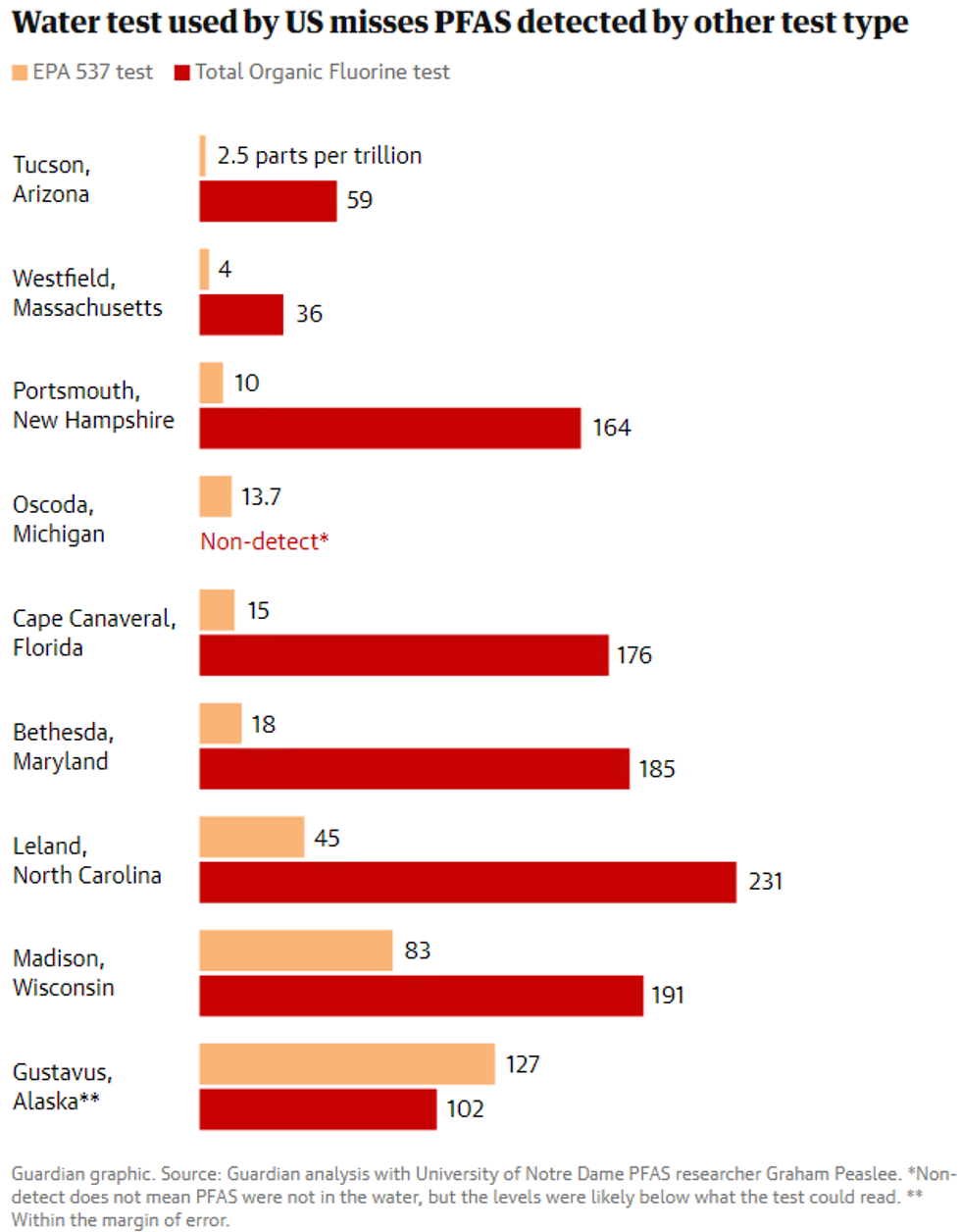

The newspaper examined water samples from the nine hot spots using two types of tests: an EPA-developed method that detects 30 types of PFAS and a more robust method that checks for a marker of the more than 9,000 PFAS compounds known to exist.

In seven of the nine cities, higher levels of PFAS were found in water samples when using a "total organic fluorine" (TOF) test that identifies markers for all known PFAS compounds than when using the EPA test--at concentrations up to 24 times greater.

"The EPA is doing the bare minimum it can and that's putting people's health at risk," said Kyla Bennett, the policy director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

PFAS are a class of synthetic compounds widely called forever chemicals because they don't fully break down--polluting people's bodies and the environment for years on end.

Scientists have linked long-term exposure to PFAS--which recent studies have identified at unsafe levels in the drinking water of more than 200 million Americans and detected in 97% of blood and 100% of breast milk samples--to numerous adverse health outcomes, including cancer, reproductive and developmental harms, immune system damage, and other negative effects.

Last month, the Biden administration unveiled what environmental groups described as "baby steps" to address toxic forever chemicals, including an allocation of $10 billion to protect drinking water from PFAS and other pollutants.

"But critics say when it comes to identifying PFAS-contaminated water, the limitations of the test used by state and federal regulators, which is called the EPA 537 method, virtually guarantees regulators will never have a full picture of contamination levels as industry churns out new compounds much faster than researchers can develop the science to measure them," The Guardian reported.

"That creates even more incentive for industry to shift away from older compounds," the newspaper noted. "If chemical companies produce newer PFAS, regulators won't be able to find the pollution."

The outlet added:

Clean water advocacy groups last year urged the EPA to use more comprehensive tests that they said would "give us a better understanding of the totality of PFAS contamination," but the agency told The Guardian it currently has no such plans.

In a statement to The Guardian, the EPA said it "continues to conduct research and monitor advances in analytical methodologies... that may improve our ability to measure more PFAS."

But that's hardly a sufficient response according to researchers such as Graham Peaslee, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who helped conduct the new analysis.

"We're looking for and studying less than 1% of PFAS so what the heck is that other 99%?" asked Peaslee. "I've never seen a good PFAS, so they're all going to have some toxicity."

Since Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974, the EPA has established maximum contaminant levels for more than 90 pollutants, but it hasn't added any new chemicals to its regulated list since 2000.

"The U.S. tap water system," the Environmental Working Group said last November after updating its national database, "is plagued by antiquated infrastructure and rampant pollution of source water, while out-of-date EPA regulations, often relying on archaic science, allow unsafe levels of toxic chemicals in drinking water."

"The EPA and industry have long argued that many newer PFAS that can't be detected are safe," The Guardian reported. "However, most new compounds have not been independently reviewed, and the types of PFAS that have been studied have been found to be toxic and persistent in the environment."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?" Bennett asked. "Why are we messing around?"

Nearly one year ago, the U.S. House passed the PFAS Action Act of 2021, which would improve federal oversight of toxic forever chemicals and facilitate clean-up efforts. The legislation has stalled in the U.S. Senate.

The testing method used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and local officials around the country is so circumscribed that regulators almost certainly have an incomplete understanding of the extent to which the nation's drinking water is contaminated with toxic "forever chemicals."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?"

That's according to The Guardian's analysis of water samples taken in nine cities with high levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) pollution, the findings of which were published Wednesday.

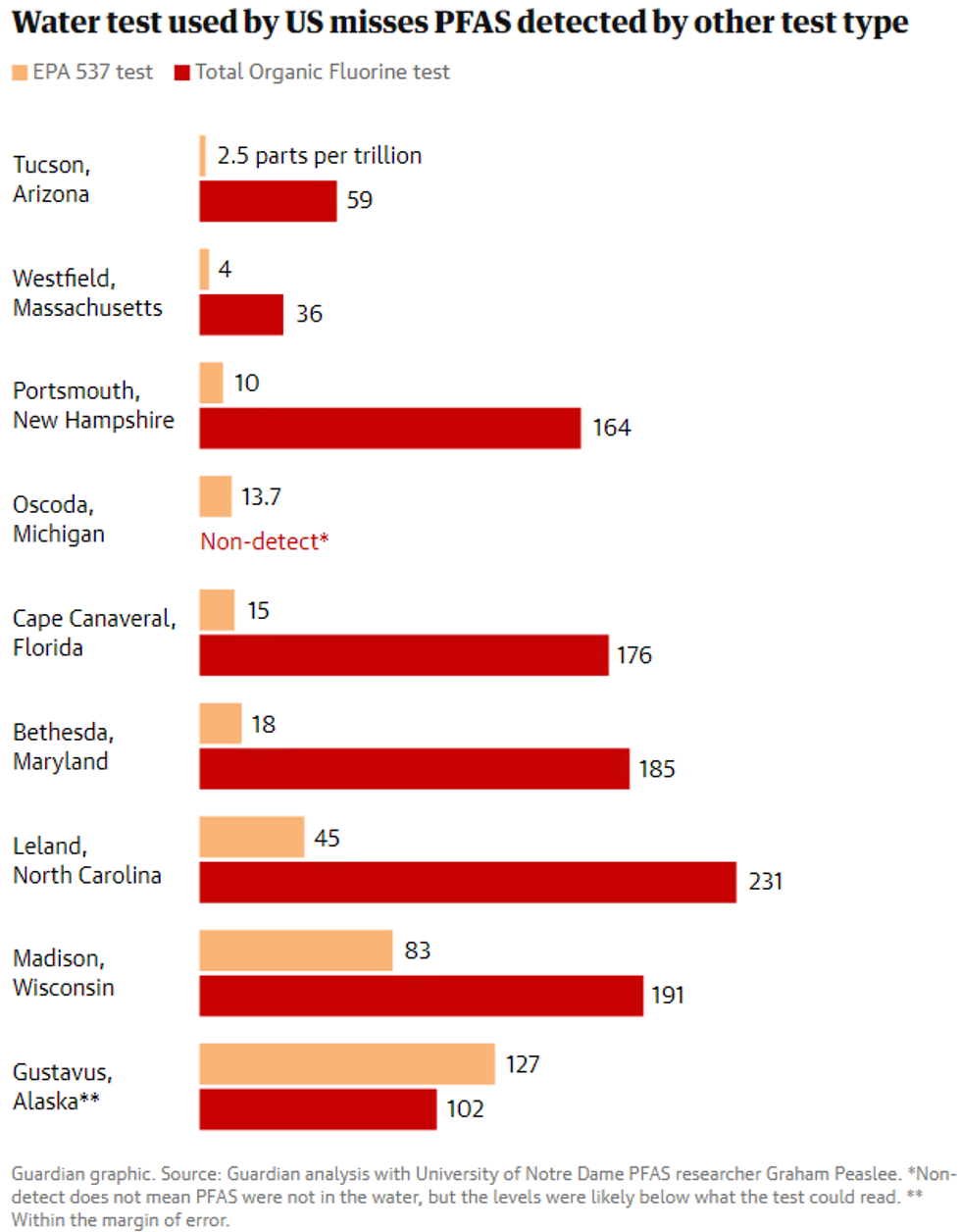

The newspaper examined water samples from the nine hot spots using two types of tests: an EPA-developed method that detects 30 types of PFAS and a more robust method that checks for a marker of the more than 9,000 PFAS compounds known to exist.

In seven of the nine cities, higher levels of PFAS were found in water samples when using a "total organic fluorine" (TOF) test that identifies markers for all known PFAS compounds than when using the EPA test--at concentrations up to 24 times greater.

"The EPA is doing the bare minimum it can and that's putting people's health at risk," said Kyla Bennett, the policy director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

PFAS are a class of synthetic compounds widely called forever chemicals because they don't fully break down--polluting people's bodies and the environment for years on end.

Scientists have linked long-term exposure to PFAS--which recent studies have identified at unsafe levels in the drinking water of more than 200 million Americans and detected in 97% of blood and 100% of breast milk samples--to numerous adverse health outcomes, including cancer, reproductive and developmental harms, immune system damage, and other negative effects.

Last month, the Biden administration unveiled what environmental groups described as "baby steps" to address toxic forever chemicals, including an allocation of $10 billion to protect drinking water from PFAS and other pollutants.

"But critics say when it comes to identifying PFAS-contaminated water, the limitations of the test used by state and federal regulators, which is called the EPA 537 method, virtually guarantees regulators will never have a full picture of contamination levels as industry churns out new compounds much faster than researchers can develop the science to measure them," The Guardian reported.

"That creates even more incentive for industry to shift away from older compounds," the newspaper noted. "If chemical companies produce newer PFAS, regulators won't be able to find the pollution."

The outlet added:

Clean water advocacy groups last year urged the EPA to use more comprehensive tests that they said would "give us a better understanding of the totality of PFAS contamination," but the agency told The Guardian it currently has no such plans.

In a statement to The Guardian, the EPA said it "continues to conduct research and monitor advances in analytical methodologies... that may improve our ability to measure more PFAS."

But that's hardly a sufficient response according to researchers such as Graham Peaslee, a professor at the University of Notre Dame who helped conduct the new analysis.

"We're looking for and studying less than 1% of PFAS so what the heck is that other 99%?" asked Peaslee. "I've never seen a good PFAS, so they're all going to have some toxicity."

Since Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974, the EPA has established maximum contaminant levels for more than 90 pollutants, but it hasn't added any new chemicals to its regulated list since 2000.

"The U.S. tap water system," the Environmental Working Group said last November after updating its national database, "is plagued by antiquated infrastructure and rampant pollution of source water, while out-of-date EPA regulations, often relying on archaic science, allow unsafe levels of toxic chemicals in drinking water."

"The EPA and industry have long argued that many newer PFAS that can't be detected are safe," The Guardian reported. "However, most new compounds have not been independently reviewed, and the types of PFAS that have been studied have been found to be toxic and persistent in the environment."

"There are so many PFAS that we don't know anything about, and if we don't know anything about them, how do we know they aren't hurting us?" Bennett asked. "Why are we messing around?"

Nearly one year ago, the U.S. House passed the PFAS Action Act of 2021, which would improve federal oversight of toxic forever chemicals and facilitate clean-up efforts. The legislation has stalled in the U.S. Senate.