SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

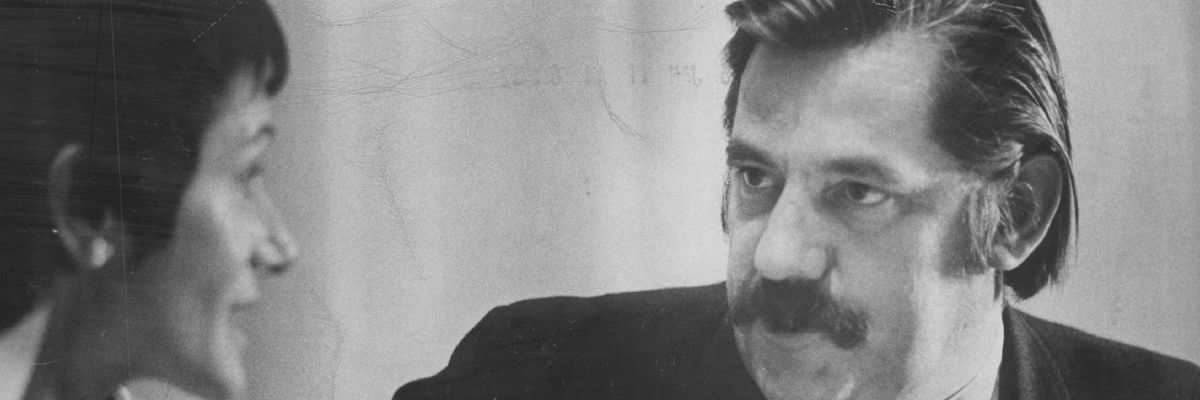

Sen. Fred Harris (right) is seen at an event on March 26, 1972.

"The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either," said Harris in 1975.

Former Oklahoma Senator Fred Harris, a moderate Democratic lawmaker who fully embraced economic populism in his later political career and ran what one journalist called a "proto-Bernie" presidential campaign in 1976, died on Saturday at the age of 94.

Harris' death inspired tributes from an array of Democratic politicians and progressives, who remembered the former senator's outspoken support for working people and his championing of Indigenous rights.

Harris was voted into the Senate to replace Sen. Robert Kerr (D-Okla.) in 1964 after Kerr died of a heart attack. He began as a close ally of President Lyndon Johnson, supporting U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and Johnson's Great Society programs aimed at reducing poverty.

But he "underwent a dramatic passage from moderate-conservative to liberal ideas," as The New York Times reported, embracing a "new populism" that was centered on promoting racial equality and a redistribution of economic and political power and fighting against the exploitation of workers. He also gradually changed his stance on Vietnam, calling for troop reductions and eventually a full withdrawal of the U.S. military in the region.

In 1967 he was a member of the Kerner Commission on Civil Disorders, convened to determine the root cause of riots in Black communities across the country. He concluded that "entrenched racism" was to blame.

He was also credited with sponsoring a bill that pushed President Richard Nixon to return Blue Lake, a site that was sacred to the people of the Taos Pueblo tribe, to them.

"In Senator Harris, Oklahoma sent a public servant to Washington, D.C. who gave voice to those in need, lifted up those the economy left behind, was a champion of civil rights, and was a friend to Indian Country," said Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. of the Cherokee Nation.

"His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."

Running for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976, Harris called for higher taxes on the richest Americans and lower taxes for the rest of the country, stricter regulations on large corporations, a "moral" foreign policy, abortion rights, and "community control" of police forces.

Columnist John Nichols of The Nation said Harris adopted the slogan "No More Bullshit" during his presidential campaign.

Harris' presidential bid, said journalist Ryan Grim of Drop Site News, "was a road-not-taken that would have led to a much better world than we have now."

Harris told the Times in 1975 that the issue he was most concerned with was "privilege."

"The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either," he said. "The widespread diffusion of economic and political power ought to be the express goal—the stated goal—of government."

Harris' campaign garnered enthusiastic support from many voters, with the former senator taking aim at "the superrich, giant corporations" and leading efforts to gain the confidence of blue-collar workers, farmers, poor Black and white voters, and unemployed people.

"Those in the coalition don't have to love one another," Harris said. "All they have to do is recognize that they are commonly exploited, and that if they get themselves together they are a popular majority and can take back the government."

After his presidential run, Harris became a political science professor at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and left politics to raise chickens on a farm in Corrales, New Mexico.

In conversations with Axios reporter Russell Contreras in his later years, Harris expressed frustration with the Democratic Party, saying leaders didn't discuss poverty as much as they should.

"It's harder to get out of poverty today than it was back then," he told Contreras.

He added that showing a commitment to fight for working-class and low-income people would motivate people in Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and on Native American reservations across the country.

"We are grateful to see national media highlighting the life and legacy of former Senator Fred Harris," said the Oklahoma Democratic Party. "His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Former Oklahoma Senator Fred Harris, a moderate Democratic lawmaker who fully embraced economic populism in his later political career and ran what one journalist called a "proto-Bernie" presidential campaign in 1976, died on Saturday at the age of 94.

Harris' death inspired tributes from an array of Democratic politicians and progressives, who remembered the former senator's outspoken support for working people and his championing of Indigenous rights.

Harris was voted into the Senate to replace Sen. Robert Kerr (D-Okla.) in 1964 after Kerr died of a heart attack. He began as a close ally of President Lyndon Johnson, supporting U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and Johnson's Great Society programs aimed at reducing poverty.

But he "underwent a dramatic passage from moderate-conservative to liberal ideas," as The New York Times reported, embracing a "new populism" that was centered on promoting racial equality and a redistribution of economic and political power and fighting against the exploitation of workers. He also gradually changed his stance on Vietnam, calling for troop reductions and eventually a full withdrawal of the U.S. military in the region.

In 1967 he was a member of the Kerner Commission on Civil Disorders, convened to determine the root cause of riots in Black communities across the country. He concluded that "entrenched racism" was to blame.

He was also credited with sponsoring a bill that pushed President Richard Nixon to return Blue Lake, a site that was sacred to the people of the Taos Pueblo tribe, to them.

"In Senator Harris, Oklahoma sent a public servant to Washington, D.C. who gave voice to those in need, lifted up those the economy left behind, was a champion of civil rights, and was a friend to Indian Country," said Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. of the Cherokee Nation.

"His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."

Running for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976, Harris called for higher taxes on the richest Americans and lower taxes for the rest of the country, stricter regulations on large corporations, a "moral" foreign policy, abortion rights, and "community control" of police forces.

Columnist John Nichols of The Nation said Harris adopted the slogan "No More Bullshit" during his presidential campaign.

Harris' presidential bid, said journalist Ryan Grim of Drop Site News, "was a road-not-taken that would have led to a much better world than we have now."

Harris told the Times in 1975 that the issue he was most concerned with was "privilege."

"The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either," he said. "The widespread diffusion of economic and political power ought to be the express goal—the stated goal—of government."

Harris' campaign garnered enthusiastic support from many voters, with the former senator taking aim at "the superrich, giant corporations" and leading efforts to gain the confidence of blue-collar workers, farmers, poor Black and white voters, and unemployed people.

"Those in the coalition don't have to love one another," Harris said. "All they have to do is recognize that they are commonly exploited, and that if they get themselves together they are a popular majority and can take back the government."

After his presidential run, Harris became a political science professor at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and left politics to raise chickens on a farm in Corrales, New Mexico.

In conversations with Axios reporter Russell Contreras in his later years, Harris expressed frustration with the Democratic Party, saying leaders didn't discuss poverty as much as they should.

"It's harder to get out of poverty today than it was back then," he told Contreras.

He added that showing a commitment to fight for working-class and low-income people would motivate people in Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and on Native American reservations across the country.

"We are grateful to see national media highlighting the life and legacy of former Senator Fred Harris," said the Oklahoma Democratic Party. "His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."

Former Oklahoma Senator Fred Harris, a moderate Democratic lawmaker who fully embraced economic populism in his later political career and ran what one journalist called a "proto-Bernie" presidential campaign in 1976, died on Saturday at the age of 94.

Harris' death inspired tributes from an array of Democratic politicians and progressives, who remembered the former senator's outspoken support for working people and his championing of Indigenous rights.

Harris was voted into the Senate to replace Sen. Robert Kerr (D-Okla.) in 1964 after Kerr died of a heart attack. He began as a close ally of President Lyndon Johnson, supporting U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War and Johnson's Great Society programs aimed at reducing poverty.

But he "underwent a dramatic passage from moderate-conservative to liberal ideas," as The New York Times reported, embracing a "new populism" that was centered on promoting racial equality and a redistribution of economic and political power and fighting against the exploitation of workers. He also gradually changed his stance on Vietnam, calling for troop reductions and eventually a full withdrawal of the U.S. military in the region.

In 1967 he was a member of the Kerner Commission on Civil Disorders, convened to determine the root cause of riots in Black communities across the country. He concluded that "entrenched racism" was to blame.

He was also credited with sponsoring a bill that pushed President Richard Nixon to return Blue Lake, a site that was sacred to the people of the Taos Pueblo tribe, to them.

"In Senator Harris, Oklahoma sent a public servant to Washington, D.C. who gave voice to those in need, lifted up those the economy left behind, was a champion of civil rights, and was a friend to Indian Country," said Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. of the Cherokee Nation.

"His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."

Running for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976, Harris called for higher taxes on the richest Americans and lower taxes for the rest of the country, stricter regulations on large corporations, a "moral" foreign policy, abortion rights, and "community control" of police forces.

Columnist John Nichols of The Nation said Harris adopted the slogan "No More Bullshit" during his presidential campaign.

Harris' presidential bid, said journalist Ryan Grim of Drop Site News, "was a road-not-taken that would have led to a much better world than we have now."

Harris told the Times in 1975 that the issue he was most concerned with was "privilege."

"The fundamental problem is that too few people have all the money and power, and everybody else has too little of either," he said. "The widespread diffusion of economic and political power ought to be the express goal—the stated goal—of government."

Harris' campaign garnered enthusiastic support from many voters, with the former senator taking aim at "the superrich, giant corporations" and leading efforts to gain the confidence of blue-collar workers, farmers, poor Black and white voters, and unemployed people.

"Those in the coalition don't have to love one another," Harris said. "All they have to do is recognize that they are commonly exploited, and that if they get themselves together they are a popular majority and can take back the government."

After his presidential run, Harris became a political science professor at the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque and left politics to raise chickens on a farm in Corrales, New Mexico.

In conversations with Axios reporter Russell Contreras in his later years, Harris expressed frustration with the Democratic Party, saying leaders didn't discuss poverty as much as they should.

"It's harder to get out of poverty today than it was back then," he told Contreras.

He added that showing a commitment to fight for working-class and low-income people would motivate people in Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and on Native American reservations across the country.

"We are grateful to see national media highlighting the life and legacy of former Senator Fred Harris," said the Oklahoma Democratic Party. "His story is one that too few people know—the story of an Oklahoman who championed working families and fought for justice and equity at every turn."