SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

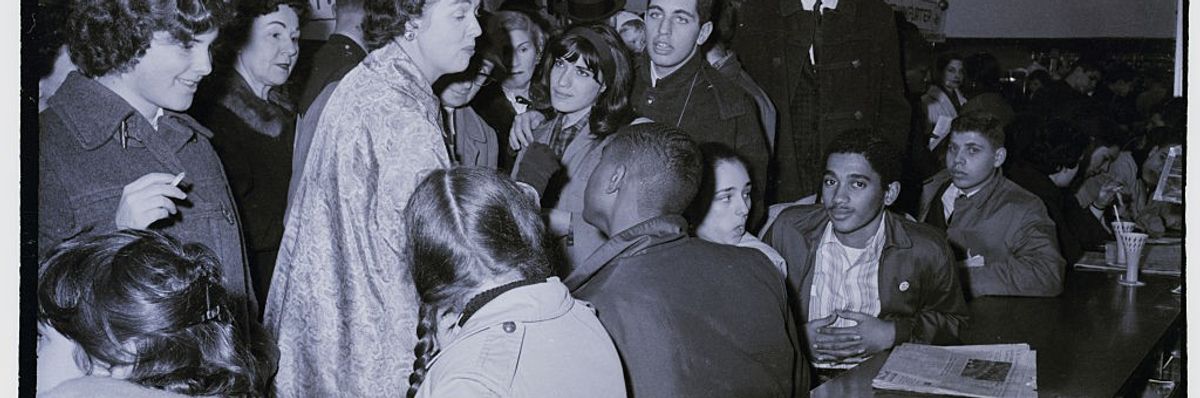

A woman unable to find a vacant seat at a F.W. Woolworth's lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina chastises demonstrators participating in a sit-down protest at the counter on April 2, 1960.

Those who decided to take action in 1960 changed the course of history. That's how change is made.

Late in the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four young black men—Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro — visited the local Woolworth’s five-and-dime store. They purchased school supplies and toothpaste, and then they sat down at the store’s lunch counter and ordered coffee.

“I’m sorry,” said the waitress. “We don’t serve Negroes here.”

The four students refused to give up their seats until the store closed. The local media soon arrived and reported the sit-in on television and in the newspapers.

The four students returned the next day with more students, and by February 5 about 300 students had joined the protest, generating more media attention. Their action inspired students at other colleges across the South to follow their example. By the end of March, sit-ins had spread to 55 cities in 13 states.

Across the South, local white thugs tried to intimidate the sit-in protesters. They pelted them with food or ketchup and tried to provoke fights. But the students remained nonviolent and didn’t fight back.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

Rather than arrest the thugs, local police arrested the protesters because what they were doing—resisting Jim Crow laws—was illegal. Over 1,500 students, mostly black but also white, were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, or disturbing the peace.

In hundreds of cities across the country, Americans of conscience—led by churches and synagogues, unions, and college students—demonstrated their support for the sit-ins by picketing in front of Woolworths stores, urging people to boycott the national chain until it desegregated its Southern lunch counters.

The Greensboro Woolworths ended its policy of segregation a few weeks after the North Carolina A&T students began their protest. Within months, hundreds of other lunch counters, department stores, and other retail businesses throughout the South announced plans to serve all customers equally. The sit-ins, the picketing by allies, the consumer boycott, and the negative publicity had worked.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

At the invitation of organizer Ella Baker and Martin Luther King, several hundred sit-in activists and their allies came to Shaw University, a black college in Raleigh, North Carolina, over Easter weekend— which was April 16-18 that year—to discuss how to capitalize on the sit-ins’ growing momentum and publicity.

This gathering became the founding meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Its growing base of supporters played key roles in the freedom rides, marches, and voter registration drives that eventually led Congress to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

At that first SNCC meeting, folksinger Guy Carawan introduced and taught the song "We Shall Overcome" to the assembled activists. They quickly adopted the song as their own, using it to sustain their morale during protest marches, on the Freedom Ride buses, and in jail cells. It quickly spread throughout the civil rights movement and became its unofficial anthem.

Many SNCC activists became key leaders in subsequent battles for social justice. One was Marion Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund. Another was Congressman John Lewis, who courageously risked his life many times for social justice, but whom an ignorant Donald Trump, in one of his outrageous online tantrums, criticized as “all talk, no action.”

The kind of protest and civil disobedience utilized by the SNCC activists continues today in campaigns for environmental justice, workers’ and immigrant rights, tenant empowerment, and an end to racism, among other causes.

The struggle continues. This is how people make history.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Late in the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four young black men—Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro — visited the local Woolworth’s five-and-dime store. They purchased school supplies and toothpaste, and then they sat down at the store’s lunch counter and ordered coffee.

“I’m sorry,” said the waitress. “We don’t serve Negroes here.”

The four students refused to give up their seats until the store closed. The local media soon arrived and reported the sit-in on television and in the newspapers.

The four students returned the next day with more students, and by February 5 about 300 students had joined the protest, generating more media attention. Their action inspired students at other colleges across the South to follow their example. By the end of March, sit-ins had spread to 55 cities in 13 states.

Across the South, local white thugs tried to intimidate the sit-in protesters. They pelted them with food or ketchup and tried to provoke fights. But the students remained nonviolent and didn’t fight back.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

Rather than arrest the thugs, local police arrested the protesters because what they were doing—resisting Jim Crow laws—was illegal. Over 1,500 students, mostly black but also white, were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, or disturbing the peace.

In hundreds of cities across the country, Americans of conscience—led by churches and synagogues, unions, and college students—demonstrated their support for the sit-ins by picketing in front of Woolworths stores, urging people to boycott the national chain until it desegregated its Southern lunch counters.

The Greensboro Woolworths ended its policy of segregation a few weeks after the North Carolina A&T students began their protest. Within months, hundreds of other lunch counters, department stores, and other retail businesses throughout the South announced plans to serve all customers equally. The sit-ins, the picketing by allies, the consumer boycott, and the negative publicity had worked.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

At the invitation of organizer Ella Baker and Martin Luther King, several hundred sit-in activists and their allies came to Shaw University, a black college in Raleigh, North Carolina, over Easter weekend— which was April 16-18 that year—to discuss how to capitalize on the sit-ins’ growing momentum and publicity.

This gathering became the founding meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Its growing base of supporters played key roles in the freedom rides, marches, and voter registration drives that eventually led Congress to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

At that first SNCC meeting, folksinger Guy Carawan introduced and taught the song "We Shall Overcome" to the assembled activists. They quickly adopted the song as their own, using it to sustain their morale during protest marches, on the Freedom Ride buses, and in jail cells. It quickly spread throughout the civil rights movement and became its unofficial anthem.

Many SNCC activists became key leaders in subsequent battles for social justice. One was Marion Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund. Another was Congressman John Lewis, who courageously risked his life many times for social justice, but whom an ignorant Donald Trump, in one of his outrageous online tantrums, criticized as “all talk, no action.”

The kind of protest and civil disobedience utilized by the SNCC activists continues today in campaigns for environmental justice, workers’ and immigrant rights, tenant empowerment, and an end to racism, among other causes.

The struggle continues. This is how people make history.

Late in the afternoon of February 1, 1960, four young black men—Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro — visited the local Woolworth’s five-and-dime store. They purchased school supplies and toothpaste, and then they sat down at the store’s lunch counter and ordered coffee.

“I’m sorry,” said the waitress. “We don’t serve Negroes here.”

The four students refused to give up their seats until the store closed. The local media soon arrived and reported the sit-in on television and in the newspapers.

The four students returned the next day with more students, and by February 5 about 300 students had joined the protest, generating more media attention. Their action inspired students at other colleges across the South to follow their example. By the end of March, sit-ins had spread to 55 cities in 13 states.

Across the South, local white thugs tried to intimidate the sit-in protesters. They pelted them with food or ketchup and tried to provoke fights. But the students remained nonviolent and didn’t fight back.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

Rather than arrest the thugs, local police arrested the protesters because what they were doing—resisting Jim Crow laws—was illegal. Over 1,500 students, mostly black but also white, were arrested for trespassing, disorderly conduct, or disturbing the peace.

In hundreds of cities across the country, Americans of conscience—led by churches and synagogues, unions, and college students—demonstrated their support for the sit-ins by picketing in front of Woolworths stores, urging people to boycott the national chain until it desegregated its Southern lunch counters.

The Greensboro Woolworths ended its policy of segregation a few weeks after the North Carolina A&T students began their protest. Within months, hundreds of other lunch counters, department stores, and other retail businesses throughout the South announced plans to serve all customers equally. The sit-ins, the picketing by allies, the consumer boycott, and the negative publicity had worked.

Most conservatives and even some liberals—black and white—thought that the student activists were too radical. But their actions galvanized a new wave of civil rights protest.

At the invitation of organizer Ella Baker and Martin Luther King, several hundred sit-in activists and their allies came to Shaw University, a black college in Raleigh, North Carolina, over Easter weekend— which was April 16-18 that year—to discuss how to capitalize on the sit-ins’ growing momentum and publicity.

This gathering became the founding meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Its growing base of supporters played key roles in the freedom rides, marches, and voter registration drives that eventually led Congress to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

At that first SNCC meeting, folksinger Guy Carawan introduced and taught the song "We Shall Overcome" to the assembled activists. They quickly adopted the song as their own, using it to sustain their morale during protest marches, on the Freedom Ride buses, and in jail cells. It quickly spread throughout the civil rights movement and became its unofficial anthem.

Many SNCC activists became key leaders in subsequent battles for social justice. One was Marion Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund. Another was Congressman John Lewis, who courageously risked his life many times for social justice, but whom an ignorant Donald Trump, in one of his outrageous online tantrums, criticized as “all talk, no action.”

The kind of protest and civil disobedience utilized by the SNCC activists continues today in campaigns for environmental justice, workers’ and immigrant rights, tenant empowerment, and an end to racism, among other causes.

The struggle continues. This is how people make history.