May 1886. As part of a national movement to win an eight-hour workday, workers at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago are on strike. Police attack, killing at least one person and injuring multiple others. The next day, labor leaders organize a peaceful mass rally at Haymarket Square. A bomb goes off, and police indiscriminately shoot protesters.

The confrontation became an international rallying cry for labor advocates, but it would be 54 more years before the 40-hour workweek became enshrined by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. A year later, the rapidly growing United Auto Workers brought to heel the Ford Motor Company—perhaps the most anti-union of the Big Three automakers at the time—by securing workers’ first collective bargaining agreement with the company.

The growth of the industrial economy, along with a militant and newly organized working class, would force meaningful concessions from capital. But the eight-hour workday and 40-hour workweek would require a global crisis—in this case, capital’s need for labor peace during World War II—to become a reality.

In a time of record corporate profits, when workers are continuously exploited and life expectancy is declining, there’s no reason workers shouldn’t demand everything.

We now have the great opportunity of existing not in the midst of a single global crisis, but a “polycrisis.”

As historian Adam Tooze writes, “In the polycrisis, the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts.”

Yes, we are potentially overwhelmed and left adrift by the convergence of a once-in-a-hundred-years pandemic, the unmasking of the deep impacts of climate change, the protracted armed conflicts in Ukraine and across Africa and the Middle East, and an uncertain transition to a future beyond neoliberal economics. But therein lies the opportunity.

Our climate future demands nothing less than a transformation of our political economy to focus on human needs over shareholder returns. Where better to start than a reimagination and recalibration of our relationship to capital and production, to the amount of time we are compelled to spend doing what Americans do best, which is to say, work?

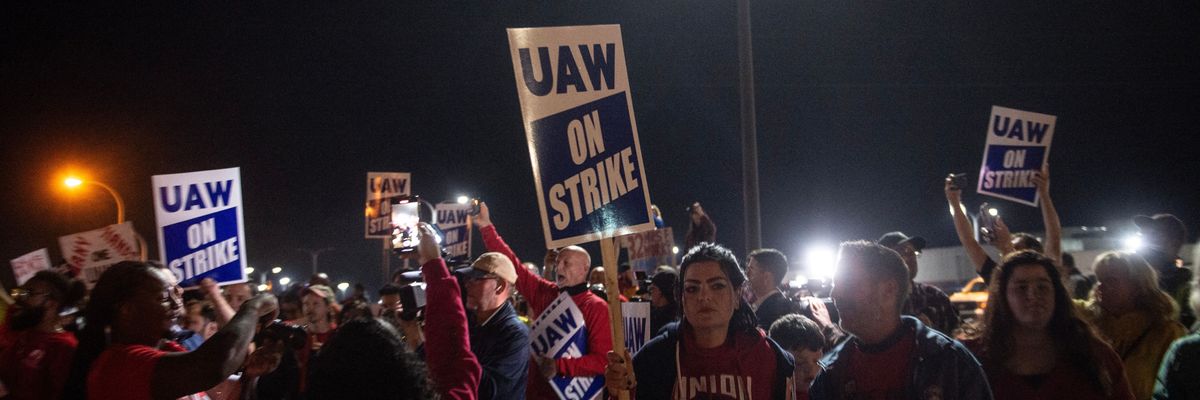

This summer, the United Auto Workers, led by its first popularly elected president, Shawn Fain, began its next contract campaign with the Big Three. A union whose strength has been gutted by decades of deindustrialization couldn’t be blamed if it chose, in a moment of enormous industry change, to mount a purely defensive fight. But the union seems to be rising to the moment and is clearly going on the offensive.

“We have to work longer and harder just to maintain the same standard of living that we had before,” Fain recently told his union. “That means more time at work, and less time living life. That means missing Little League games and family reunions. It means less time outdoors, less time traveling, less time pursuing our passions and our hobbies.”

Fain is demanding a 32-hour workweek, a reasonable demand that has the potential to help meet part of our current crises. And we should all be asking for more. In a time of record corporate profits, when workers are continuously exploited and life expectancy is declining, there’s no reason workers shouldn’t demand everything.

A 20-hour workweek would require the kind of shift in economic common sense necessary for a future worth living. Our ability to imagine that livable climate future depends upon our ability to connect with each other, to take care of the basic needs of our society, to create meaningful work for all. In a polycrisis, we can’t tinker around the edges. To create the world we need, we must make the kind of demands that can deliver real transformation.

Of course, we’ll take 32 today. And we’ll use those eight hours to organize for tomorrow.