SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

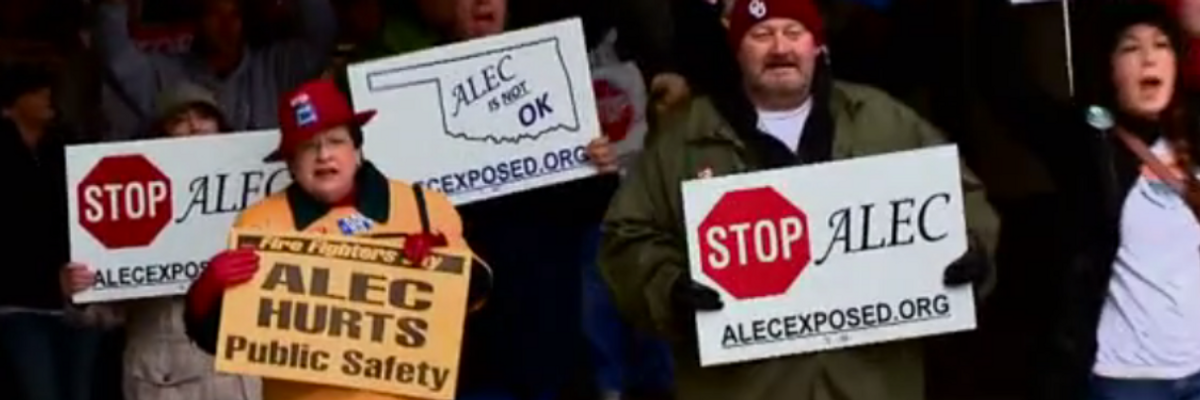

Citizens protesting ALEC outside a meeting of the group in Oklahoma in 2013. ALEC will hold its 44th annual convention this year in Denver on July 19-21.

For years right-wing operatives including ALEC, the State Policy Network (SPN), and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) have been waging an assault against disclosure and transparency laws at the state level.

Seventeen states have enacted broad anti-disclosure laws since 2018 that will further conceal the influence of dark money in politics based on model language first developed by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Indiana, Kentucky, and Alabama are the most recent states to pass versions of the so-called “Personal Privacy Protection Act” being championed by ALEC and allied right-wing groups claiming to be defenders of the First Amendment.

Most versions of the bill broadly prohibit state agencies from gathering information about donors to nonprofit organizations, and some go further to shelter nonprofits from political spending disclosure rules and even immunize dark money groups from campaign finance investigations.

For years right-wing operatives including ALEC, the State Policy Network (SPN), and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) have been waging an assault against disclosure and transparency laws. As the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) reported, that culminated in a favorable Koch-bankrolled 2021 Supreme Court ruling barring California from collecting the exact same information on major donors required by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

IRS regulations require nonprofits to disclose their largest donors. Though the information is not available to the public, it has traditionally been shared with state governments to aid in investigations of fraud.

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws.”

Opponents of disclosure rules argue that conservative donors face discrimination and unwanted scrutiny by the federal government. They rely heavily on the 1958 Supreme Court case NAACP v. Alabama—which upheld the Black civil rights organization’s prerogative to refuse to disclose its membership for fear of retribution—to make their case for keeping the identity of donors secret. This comes in the midst of national fear-mongering by Republicans—spearheaded by the House Panel on the Weaponization of the Federal Government—about how social media companies and disinformation researchers are colluding with the federal government to suppress conservative speech.

“What has been going on for a number of years now is that leftist organizations—George Soros-funded organizations and entities—have been working to try to force disclosure of donors to nonprofit organizations,” according to far-right legal operative Cleta Mitchell, current head of the Conservative Partnership Institute’s voter-suppression group, the Elections Integrity Network.

“They want to do that because they want a target list of donors to conservative organizations so that they can intimidate and chill the willingness of conservatives to give money to conservative issue groups,” Mitchell continued, speaking at a recent ALEC gathering.

In 2016, ALEC introduced both its Resolution in Support of Nonprofit Donor Privacy, and later published a Donor Disclosure Legislative Toolkit, in “response to attempts to expand the scope and application of donor disclosure requirements of nonprofit tax-exempt organizations.” The same year, SPN founded People United for Privacy (PUFP)—which later spun off into its own nonprofit—in order to push for anti-disclosure legislation.

A PUFP messaging kit distributed at the SPN 2019 Annual Meeting produced by Heart Mind strategies and obtained by CMD calls nonprofit donor disclosure a “problem” and provides tips on how to spin opposition to it in terms of “privacy,” “free speech,” and personal harassment.

Since 2018, ALEC’s model anti-disclosure legislation has picked up speed in state legislatures. A majority of the bills that have passed have been sponsored by ALEC politicians, with wording lifted directly from ALEC’s anti-disclosure playbook, though many local groups have lobbied in favor of the bills.

PUFP appears to be leading the charge in public advocacy of the Personal Privacy Protection Act (PPPA) bills based on ALEC’s resolution. In recent years, the group and its related foundation have received $1.1 million from SPN and $1.4 million from DonorsTrust, the preferred funding vehicle for Koch network donors.

“While each state’s version of the law varies to fit its particular needs,” PUFP said in a statement on PPPA legislation, “the fundamental principle is always the same: The PPPA prohibits state agencies and officials from demanding or publicly disclosing information about an individual’s support for nonprofit causes.”

Arizona was the first state to pass a version of the PPPA (HB 2153), as CMD reported in 2018. Former State Representative Vince Leach (R-11), who went on to serve four years in the state senate (2019–23), sponsored the bill. He had been a member of ALEC since at least 2020, and in mid January 2021, he participated in an ALEC gathering with the radical right group Turning Point USA, which played a key role in promoting former President Trump’s false claims of widespread voter fraud.

In 2019, Mississippi became the second state to embrace PPPA legislation. State Representative Jerry R. Turner (R-18), the principal author of HB 1205, first joined ALEC in 2016 and served on its Education and Workforce Development task force. Six of the eight other authors were also ALEC members.

The campaign to curb transparency picked up speed in 2020, when three states—Oklahoma (HB 3613), Utah (SB 171), and West Virginia (SB 16)—all passed similar legislation with primary sponsors who were ALEC members.

In 2021, the trend shifted slightly, with an ALEC sponsor involved in only one of the four states (Tennessee, Arkansas, Iowa, and South Dakota) that passed PPPA legislation. That was in Arkansas, where the bill was sponsored by a current ALEC state chair. In South Dakota, the legislation was a priority of former ALEC member and current Republican Governor Kristi Noem.

In 2021, the New York legislature also passed a limited bill—signed into law by Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul—which curbed donor transparency, a move considered by the conservative Philanthropy Roundtable as “an important step in defending the privacy of donors.”

The three states that successfully passed PPPA legislation this year—through SB 59 in Alabama, HB 1212 in Indiana, and SB 62 in Kentucky—built on the four states that succeeded in 2022: Virginia (HB 970), Kansas (HB 2109), Missouri (HB 2400), and New Hampshire (SB 302). This year legislation died in committee in Nebraska (LB 297) and Pennsylvania (SB 831).

In recent years, a number of attempts to pass PPPA legislation have failed, either in state legislatures or due to gubernatorial vetoes.

In 2018, then Governor Rick Snyder (R) vetoed a similar bill (SB 1176) in Michigan that passed in the state legislature, saying: “I believe this legislation is a solution in search of a problem that does not exist in Michigan.” The bill had been sponsored by State Senator Mike Shirkey (R-16), who attended ALEC’s 2020 States and Nation Policy Summit. In vetoing North Carolina’s SB 636 in 2021, Democratic Governor Roy Cooper pointed out that the bill was “unnecessary and may limit transparency with political contributions.”

Louisiana Representative Mark Wright (R-77), the current ALEC state chair, proposed HB 303 in 2020 but it died in committee.

This year one of the first big blowbacks to the model legislation erupted after concerns were raised over its impact on government transparency. Reform legislation has been proposed in Missouri after Republican Governor Mike Parson shut down access to state contracts and cited the recently enacted PPPA as justification for withholding information about a fundraiser held at the governor’s mansion.

ALEC’s and PUFP’s model legislation has morphed over the years as it has enjoyed successes and suffered failures in various state legislatures, according to Aaron McKean, legal counsel for state and local reform at the Campaign Legal Center.

“If you look at how these bills develop, you can see that they start from a poorly conceived and unnecessary model bill and then they become riddled with exceptions, to such an extent that you have to wonder what the real motivations are, what’s really left,” McKean told CMD. “It just goes to show how poorly these bills are drafted.”

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws,” said Viki Harrison, Director of Constitutional Convention and Protecting Dissent Programs at Common Cause.

This year’s PPPA legislation in Alabama was the first introduced by a Democratic lawmaker—State Senator Rodger Smitherman (D-18), who also introduced a successful amendment to include lawmakers in existing legislation that exempts judges, law enforcement officers, and prosecutors from needing to release their personal information. The senator’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Indeed, advocacy around anti-disclosure measures has made for some unusual bedfellows. The ACLU regularly argues in favor of such legislation alongside AFP. Proponents of PPPA are quick to argue that anti-disclosure legislation is bipartisan, eager to cite what they call “ideological diversity.”

PUFP had previously led a coalition that opposed the For the People Act (HR 1), the 2021 voting rights bill backed by House Democrats that would have significantly enhanced nonprofit donor transparency.

This week House Republicans introduced an omnibus bill called the American Confidence in Elections (ACE) Act that they tout as the “most conservative election integrity bill to be seriously considered in the House in over 20 years.” Senate Majority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has vowed that the Senate will not consider the legislation this session, according to Roll Call.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Seventeen states have enacted broad anti-disclosure laws since 2018 that will further conceal the influence of dark money in politics based on model language first developed by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Indiana, Kentucky, and Alabama are the most recent states to pass versions of the so-called “Personal Privacy Protection Act” being championed by ALEC and allied right-wing groups claiming to be defenders of the First Amendment.

Most versions of the bill broadly prohibit state agencies from gathering information about donors to nonprofit organizations, and some go further to shelter nonprofits from political spending disclosure rules and even immunize dark money groups from campaign finance investigations.

For years right-wing operatives including ALEC, the State Policy Network (SPN), and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) have been waging an assault against disclosure and transparency laws. As the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) reported, that culminated in a favorable Koch-bankrolled 2021 Supreme Court ruling barring California from collecting the exact same information on major donors required by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

IRS regulations require nonprofits to disclose their largest donors. Though the information is not available to the public, it has traditionally been shared with state governments to aid in investigations of fraud.

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws.”

Opponents of disclosure rules argue that conservative donors face discrimination and unwanted scrutiny by the federal government. They rely heavily on the 1958 Supreme Court case NAACP v. Alabama—which upheld the Black civil rights organization’s prerogative to refuse to disclose its membership for fear of retribution—to make their case for keeping the identity of donors secret. This comes in the midst of national fear-mongering by Republicans—spearheaded by the House Panel on the Weaponization of the Federal Government—about how social media companies and disinformation researchers are colluding with the federal government to suppress conservative speech.

“What has been going on for a number of years now is that leftist organizations—George Soros-funded organizations and entities—have been working to try to force disclosure of donors to nonprofit organizations,” according to far-right legal operative Cleta Mitchell, current head of the Conservative Partnership Institute’s voter-suppression group, the Elections Integrity Network.

“They want to do that because they want a target list of donors to conservative organizations so that they can intimidate and chill the willingness of conservatives to give money to conservative issue groups,” Mitchell continued, speaking at a recent ALEC gathering.

In 2016, ALEC introduced both its Resolution in Support of Nonprofit Donor Privacy, and later published a Donor Disclosure Legislative Toolkit, in “response to attempts to expand the scope and application of donor disclosure requirements of nonprofit tax-exempt organizations.” The same year, SPN founded People United for Privacy (PUFP)—which later spun off into its own nonprofit—in order to push for anti-disclosure legislation.

A PUFP messaging kit distributed at the SPN 2019 Annual Meeting produced by Heart Mind strategies and obtained by CMD calls nonprofit donor disclosure a “problem” and provides tips on how to spin opposition to it in terms of “privacy,” “free speech,” and personal harassment.

Since 2018, ALEC’s model anti-disclosure legislation has picked up speed in state legislatures. A majority of the bills that have passed have been sponsored by ALEC politicians, with wording lifted directly from ALEC’s anti-disclosure playbook, though many local groups have lobbied in favor of the bills.

PUFP appears to be leading the charge in public advocacy of the Personal Privacy Protection Act (PPPA) bills based on ALEC’s resolution. In recent years, the group and its related foundation have received $1.1 million from SPN and $1.4 million from DonorsTrust, the preferred funding vehicle for Koch network donors.

“While each state’s version of the law varies to fit its particular needs,” PUFP said in a statement on PPPA legislation, “the fundamental principle is always the same: The PPPA prohibits state agencies and officials from demanding or publicly disclosing information about an individual’s support for nonprofit causes.”

Arizona was the first state to pass a version of the PPPA (HB 2153), as CMD reported in 2018. Former State Representative Vince Leach (R-11), who went on to serve four years in the state senate (2019–23), sponsored the bill. He had been a member of ALEC since at least 2020, and in mid January 2021, he participated in an ALEC gathering with the radical right group Turning Point USA, which played a key role in promoting former President Trump’s false claims of widespread voter fraud.

In 2019, Mississippi became the second state to embrace PPPA legislation. State Representative Jerry R. Turner (R-18), the principal author of HB 1205, first joined ALEC in 2016 and served on its Education and Workforce Development task force. Six of the eight other authors were also ALEC members.

The campaign to curb transparency picked up speed in 2020, when three states—Oklahoma (HB 3613), Utah (SB 171), and West Virginia (SB 16)—all passed similar legislation with primary sponsors who were ALEC members.

In 2021, the trend shifted slightly, with an ALEC sponsor involved in only one of the four states (Tennessee, Arkansas, Iowa, and South Dakota) that passed PPPA legislation. That was in Arkansas, where the bill was sponsored by a current ALEC state chair. In South Dakota, the legislation was a priority of former ALEC member and current Republican Governor Kristi Noem.

In 2021, the New York legislature also passed a limited bill—signed into law by Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul—which curbed donor transparency, a move considered by the conservative Philanthropy Roundtable as “an important step in defending the privacy of donors.”

The three states that successfully passed PPPA legislation this year—through SB 59 in Alabama, HB 1212 in Indiana, and SB 62 in Kentucky—built on the four states that succeeded in 2022: Virginia (HB 970), Kansas (HB 2109), Missouri (HB 2400), and New Hampshire (SB 302). This year legislation died in committee in Nebraska (LB 297) and Pennsylvania (SB 831).

In recent years, a number of attempts to pass PPPA legislation have failed, either in state legislatures or due to gubernatorial vetoes.

In 2018, then Governor Rick Snyder (R) vetoed a similar bill (SB 1176) in Michigan that passed in the state legislature, saying: “I believe this legislation is a solution in search of a problem that does not exist in Michigan.” The bill had been sponsored by State Senator Mike Shirkey (R-16), who attended ALEC’s 2020 States and Nation Policy Summit. In vetoing North Carolina’s SB 636 in 2021, Democratic Governor Roy Cooper pointed out that the bill was “unnecessary and may limit transparency with political contributions.”

Louisiana Representative Mark Wright (R-77), the current ALEC state chair, proposed HB 303 in 2020 but it died in committee.

This year one of the first big blowbacks to the model legislation erupted after concerns were raised over its impact on government transparency. Reform legislation has been proposed in Missouri after Republican Governor Mike Parson shut down access to state contracts and cited the recently enacted PPPA as justification for withholding information about a fundraiser held at the governor’s mansion.

ALEC’s and PUFP’s model legislation has morphed over the years as it has enjoyed successes and suffered failures in various state legislatures, according to Aaron McKean, legal counsel for state and local reform at the Campaign Legal Center.

“If you look at how these bills develop, you can see that they start from a poorly conceived and unnecessary model bill and then they become riddled with exceptions, to such an extent that you have to wonder what the real motivations are, what’s really left,” McKean told CMD. “It just goes to show how poorly these bills are drafted.”

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws,” said Viki Harrison, Director of Constitutional Convention and Protecting Dissent Programs at Common Cause.

This year’s PPPA legislation in Alabama was the first introduced by a Democratic lawmaker—State Senator Rodger Smitherman (D-18), who also introduced a successful amendment to include lawmakers in existing legislation that exempts judges, law enforcement officers, and prosecutors from needing to release their personal information. The senator’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Indeed, advocacy around anti-disclosure measures has made for some unusual bedfellows. The ACLU regularly argues in favor of such legislation alongside AFP. Proponents of PPPA are quick to argue that anti-disclosure legislation is bipartisan, eager to cite what they call “ideological diversity.”

PUFP had previously led a coalition that opposed the For the People Act (HR 1), the 2021 voting rights bill backed by House Democrats that would have significantly enhanced nonprofit donor transparency.

This week House Republicans introduced an omnibus bill called the American Confidence in Elections (ACE) Act that they tout as the “most conservative election integrity bill to be seriously considered in the House in over 20 years.” Senate Majority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has vowed that the Senate will not consider the legislation this session, according to Roll Call.

Seventeen states have enacted broad anti-disclosure laws since 2018 that will further conceal the influence of dark money in politics based on model language first developed by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). Indiana, Kentucky, and Alabama are the most recent states to pass versions of the so-called “Personal Privacy Protection Act” being championed by ALEC and allied right-wing groups claiming to be defenders of the First Amendment.

Most versions of the bill broadly prohibit state agencies from gathering information about donors to nonprofit organizations, and some go further to shelter nonprofits from political spending disclosure rules and even immunize dark money groups from campaign finance investigations.

For years right-wing operatives including ALEC, the State Policy Network (SPN), and Americans for Prosperity (AFP) have been waging an assault against disclosure and transparency laws. As the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) reported, that culminated in a favorable Koch-bankrolled 2021 Supreme Court ruling barring California from collecting the exact same information on major donors required by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

IRS regulations require nonprofits to disclose their largest donors. Though the information is not available to the public, it has traditionally been shared with state governments to aid in investigations of fraud.

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws.”

Opponents of disclosure rules argue that conservative donors face discrimination and unwanted scrutiny by the federal government. They rely heavily on the 1958 Supreme Court case NAACP v. Alabama—which upheld the Black civil rights organization’s prerogative to refuse to disclose its membership for fear of retribution—to make their case for keeping the identity of donors secret. This comes in the midst of national fear-mongering by Republicans—spearheaded by the House Panel on the Weaponization of the Federal Government—about how social media companies and disinformation researchers are colluding with the federal government to suppress conservative speech.

“What has been going on for a number of years now is that leftist organizations—George Soros-funded organizations and entities—have been working to try to force disclosure of donors to nonprofit organizations,” according to far-right legal operative Cleta Mitchell, current head of the Conservative Partnership Institute’s voter-suppression group, the Elections Integrity Network.

“They want to do that because they want a target list of donors to conservative organizations so that they can intimidate and chill the willingness of conservatives to give money to conservative issue groups,” Mitchell continued, speaking at a recent ALEC gathering.

In 2016, ALEC introduced both its Resolution in Support of Nonprofit Donor Privacy, and later published a Donor Disclosure Legislative Toolkit, in “response to attempts to expand the scope and application of donor disclosure requirements of nonprofit tax-exempt organizations.” The same year, SPN founded People United for Privacy (PUFP)—which later spun off into its own nonprofit—in order to push for anti-disclosure legislation.

A PUFP messaging kit distributed at the SPN 2019 Annual Meeting produced by Heart Mind strategies and obtained by CMD calls nonprofit donor disclosure a “problem” and provides tips on how to spin opposition to it in terms of “privacy,” “free speech,” and personal harassment.

Since 2018, ALEC’s model anti-disclosure legislation has picked up speed in state legislatures. A majority of the bills that have passed have been sponsored by ALEC politicians, with wording lifted directly from ALEC’s anti-disclosure playbook, though many local groups have lobbied in favor of the bills.

PUFP appears to be leading the charge in public advocacy of the Personal Privacy Protection Act (PPPA) bills based on ALEC’s resolution. In recent years, the group and its related foundation have received $1.1 million from SPN and $1.4 million from DonorsTrust, the preferred funding vehicle for Koch network donors.

“While each state’s version of the law varies to fit its particular needs,” PUFP said in a statement on PPPA legislation, “the fundamental principle is always the same: The PPPA prohibits state agencies and officials from demanding or publicly disclosing information about an individual’s support for nonprofit causes.”

Arizona was the first state to pass a version of the PPPA (HB 2153), as CMD reported in 2018. Former State Representative Vince Leach (R-11), who went on to serve four years in the state senate (2019–23), sponsored the bill. He had been a member of ALEC since at least 2020, and in mid January 2021, he participated in an ALEC gathering with the radical right group Turning Point USA, which played a key role in promoting former President Trump’s false claims of widespread voter fraud.

In 2019, Mississippi became the second state to embrace PPPA legislation. State Representative Jerry R. Turner (R-18), the principal author of HB 1205, first joined ALEC in 2016 and served on its Education and Workforce Development task force. Six of the eight other authors were also ALEC members.

The campaign to curb transparency picked up speed in 2020, when three states—Oklahoma (HB 3613), Utah (SB 171), and West Virginia (SB 16)—all passed similar legislation with primary sponsors who were ALEC members.

In 2021, the trend shifted slightly, with an ALEC sponsor involved in only one of the four states (Tennessee, Arkansas, Iowa, and South Dakota) that passed PPPA legislation. That was in Arkansas, where the bill was sponsored by a current ALEC state chair. In South Dakota, the legislation was a priority of former ALEC member and current Republican Governor Kristi Noem.

In 2021, the New York legislature also passed a limited bill—signed into law by Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul—which curbed donor transparency, a move considered by the conservative Philanthropy Roundtable as “an important step in defending the privacy of donors.”

The three states that successfully passed PPPA legislation this year—through SB 59 in Alabama, HB 1212 in Indiana, and SB 62 in Kentucky—built on the four states that succeeded in 2022: Virginia (HB 970), Kansas (HB 2109), Missouri (HB 2400), and New Hampshire (SB 302). This year legislation died in committee in Nebraska (LB 297) and Pennsylvania (SB 831).

In recent years, a number of attempts to pass PPPA legislation have failed, either in state legislatures or due to gubernatorial vetoes.

In 2018, then Governor Rick Snyder (R) vetoed a similar bill (SB 1176) in Michigan that passed in the state legislature, saying: “I believe this legislation is a solution in search of a problem that does not exist in Michigan.” The bill had been sponsored by State Senator Mike Shirkey (R-16), who attended ALEC’s 2020 States and Nation Policy Summit. In vetoing North Carolina’s SB 636 in 2021, Democratic Governor Roy Cooper pointed out that the bill was “unnecessary and may limit transparency with political contributions.”

Louisiana Representative Mark Wright (R-77), the current ALEC state chair, proposed HB 303 in 2020 but it died in committee.

This year one of the first big blowbacks to the model legislation erupted after concerns were raised over its impact on government transparency. Reform legislation has been proposed in Missouri after Republican Governor Mike Parson shut down access to state contracts and cited the recently enacted PPPA as justification for withholding information about a fundraiser held at the governor’s mansion.

ALEC’s and PUFP’s model legislation has morphed over the years as it has enjoyed successes and suffered failures in various state legislatures, according to Aaron McKean, legal counsel for state and local reform at the Campaign Legal Center.

“If you look at how these bills develop, you can see that they start from a poorly conceived and unnecessary model bill and then they become riddled with exceptions, to such an extent that you have to wonder what the real motivations are, what’s really left,” McKean told CMD. “It just goes to show how poorly these bills are drafted.”

“ALEC’s anti-disclosure legislation is an open invitation to corruption and is being used to circumvent the most basic disclosure laws,” said Viki Harrison, Director of Constitutional Convention and Protecting Dissent Programs at Common Cause.

This year’s PPPA legislation in Alabama was the first introduced by a Democratic lawmaker—State Senator Rodger Smitherman (D-18), who also introduced a successful amendment to include lawmakers in existing legislation that exempts judges, law enforcement officers, and prosecutors from needing to release their personal information. The senator’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Indeed, advocacy around anti-disclosure measures has made for some unusual bedfellows. The ACLU regularly argues in favor of such legislation alongside AFP. Proponents of PPPA are quick to argue that anti-disclosure legislation is bipartisan, eager to cite what they call “ideological diversity.”

PUFP had previously led a coalition that opposed the For the People Act (HR 1), the 2021 voting rights bill backed by House Democrats that would have significantly enhanced nonprofit donor transparency.

This week House Republicans introduced an omnibus bill called the American Confidence in Elections (ACE) Act that they tout as the “most conservative election integrity bill to be seriously considered in the House in over 20 years.” Senate Majority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has vowed that the Senate will not consider the legislation this session, according to Roll Call.