The debate over the Federal Reserve’s proper course of action for the rest of 2023 was getting a little stagnant in recent months. The argument centered on whether inflation’s persistence was really a sign of an overheated economy that still needed cooling or if it was due to stubbornly large—but dampening—ripples stemming from the huge pandemic and war shocks of previous years. The recent failures of Silicon Valley and Signature banks and chaos in other corners of the banking sector definitely provide a new twist to this debate.

My view on what the Fed should do now in the wake of banking failures is relatively straight-forward:

- Before the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failure, it was already clear that the Fed should pause interest rate hikes at this week’s meeting, based largely on consistent deceleration of nominal wage growth.

- The SVB failure and subsequent banking turmoil are far more likely to be demand-destroying events than not. If one thought the Fed already should be reducing the pace of their rate hikes (or even pausing entirely) due to labor market cooling, the fallout from SVB just means this cooling will happen more quickly and hence the case for halting further rate hikes is stronger.

- It is a genuine problem that interest rate hikes of nearly 5% in a year cause this much distress in the financial sector, indicating a clear failure of bank management and supervision. These failures should be addressed going forward. But they exist today and the fallout of them clearly provides another argument for standing pat on further rate increases.

Even before SVB failure, labor market cooling argued for no further rate hikes

The January consumer price index (CPI) data came in uncomfortably hot after months of good readings. The February CPI data showed a largely sideways movement in inflation. Worse, revisions to 2022 CPI data showed more disinflation in mid-2022 and less in late 2022—providing slightly weaker evidence of consistent disinflation over the course of the year.

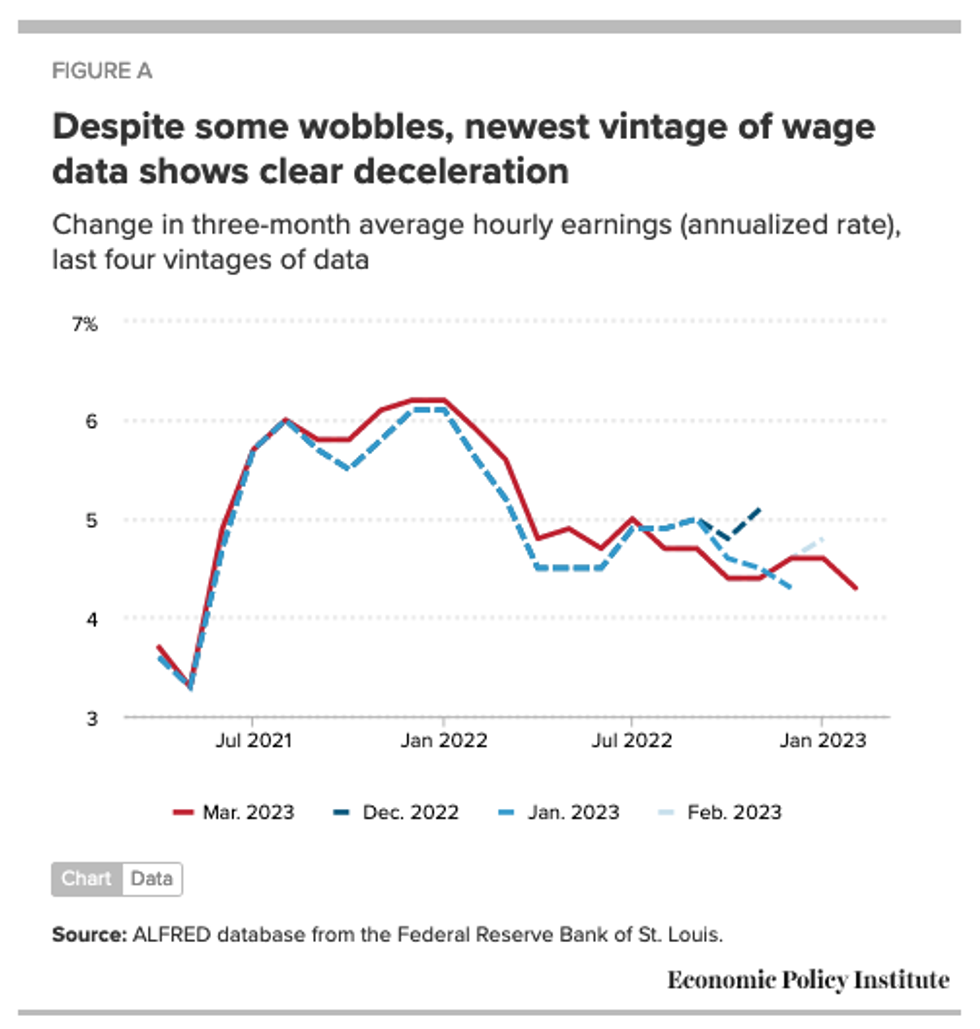

However, nominal wage growth—what many have called a “supercore” measure of inflation—has consistently cooled over the course of 2022 and early 2023. Occasionally a single month of data has shown an uptick of wage growth and concerns are raised, but new data then show continued cooling. Figure A below shows annualized rates of wage growth for the latest three months relative to the prior three months. It shows these rates of wage growth for the initial releases of this data from December 2022 to March 2023. While wage growth blipped up in the December 2022 and February 2023 reports, the most recent report shows a clear pattern of consistent nominal wage deceleration.

This deceleration of nominal wage growth should be near-dispositive for arguments about the proper path of interest rates. If the Fed is insistent on 2% price inflation in the long run, this implies that nominal wages can grow at this 2% inflation rate plus the rate of productivity growth, which we will take as 1.5%. This 3.5% wage growth target, however, assumes no increase in the share of total income accruing to labor rather than capital. Given the large decline in labor’s share of income so far in the pandemic-driven business cycle, this means that several years of wage growth as high as 4.5% could be sustained while still seeing price inflation at the Fed’s 2% target. Nominal wage growth (as shown in Figure A) has been running at or below 4.5% for several months now. In short, wage growth is now running where it should be given the state of the business cycle and the Fed’s 2% inflation target—meaning the Fed should stand pat on any further interest rate hikes.

Besides the fact that current wage growth is consistent with the Fed’s inflation target on the cost side, the rapid normalization of nominal wage growth should also lead to rapid normalization of nominal aggregate demand. Essentially, if overheated demand is not being buoyed by above-target wage growth, it is hard to see how it could continue. The allegedly excess fiscal boost from the American Rescue Plan (and even the “excess savings” banked from this aid) is long gone. Financial and housing markets have lost significant value in recent months. Without excess wage growth, any excess of demand growth is unlikely to be sustained.

Banking stresses are likely to destroy demand in coming year

The failures of SVB and Signature banks and the associated increased stress in the banking sector are far more likely to reduce economy-wide demand in coming months than to increase it. As lending standards tighten and risk premiums rise for private lending, both consumer spending and business investment are likely to be curtailed. In short, whatever your estimate of the path of demand over the next year before SVB’s failure, your estimate now should be significantly lower. This has been recently acknowledged explicitly by the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Eric Rosengren, who noted: “Financial crises create demand destruction. Banks reduce credit availability, consumers hold off large purchases, businesses defer spending. Interest rates should pause until the degree of demand destruction can be evaluated.”

There has been a recent debate in macroeconomic circles about the lags of monetary policy. Traditionally, these lags were thought to be “long and variable.” This would mean that a large part of the contractionary effect of the interest rate increases undertaken in 2022 and earlier this year had yet to hit the economy and would slow growth going forward even if the Fed stopped raising rates today. A newly fashionable view argues that these lags are shorter in today’s economy, meaning that the full contractionary effect of recent rate increases had already been absorbed by the economy and that a pause in rate-hiking would implicitly provide a substantial spur to demand growth. Whatever the outcome of this debate in normal times, the SVB failures clearly show that fallout from past rate increases is ongoing.

Yes, it’s a problem for macroeconomic stabilization that the banking system is this fragile

If one was worried that macroeconomic overheating remained a problem in the U.S. economy and was a key driver of inflation, the pressure to stop raising rates imposed by recent banking stress is extremely troubling. From this point of view, the recent banking stresses are demanding the Federal Reserve sacrifice efforts to cool the economy to control inflation in favor of the needs of financial stability.

It is especially perverse that increasing interest rates has appeared to throw much of the banking system into chaos. It is extremely well-documented that bank profitability is higher when interest rates are higher. However, it seems that banks cannot even make the transition to a new interest rate regime that would be highly favorable for them without substantial turmoil.

For all these reasons, if one was an inflation hawk who thought interest rates needed to be raised further, the imperative to stop raising rates now based on stresses in the banking system is an extremely dangerous development. And, in fact, even if one did not think that rates needed to be raised further in order to contain inflation, it’s still a bad thing that our financial system has become so fragile that raising rates causes these kinds of tremors. Even if I don’t think the economy needs higher interest rates today, there may be a future where higher interest rates would benefit the economy—and it would be very bad if macroeconomic stabilization options were held hostage to a fragile financial system.

These considerations argue strongly for improved regulatory and supervisory actions moving forward. The rollback of Dodd-Frank regulations in 2018 was a terrible step backwards in this regard. Further, the Federal Reserve rolled back regulatory safeguards even further than the 2018 law made necessary. Today’s hawks (and those like me who want to preserve the option of raising interest rates at some point in the future) should be among the most strident proponents for tightening these regulatory standards back up, and for holding the Fed accountable for supervisory failures.

But for now, the banking system is fragile and recent rate hikes have put stress on the system (as maddening as all of this is). This fragility is likely to cool the economy in coming months. Given this, any reasonable estimate of where interest rates should have gone in 2023 made before the SVB collapse should be marked down since.