SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

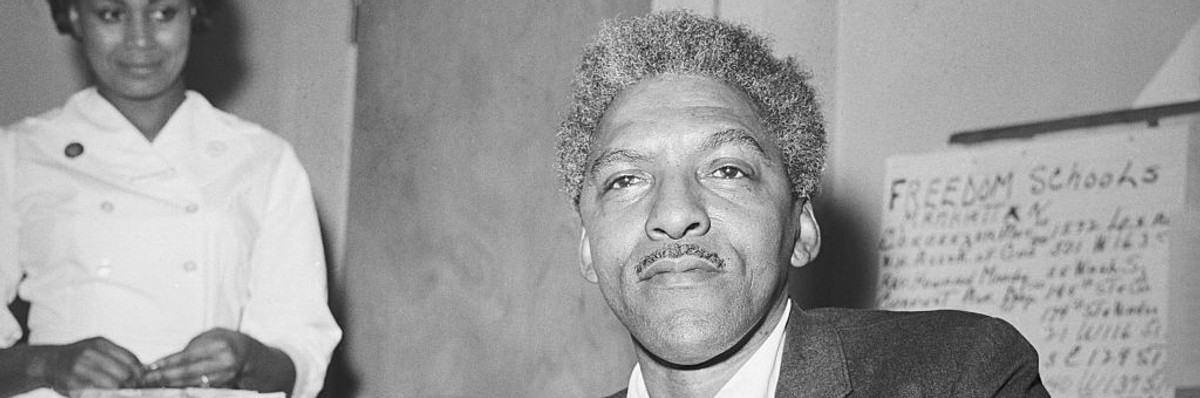

Civil rights leader Bayard Rustin pictured in February of 1964.

What’s crucial to understand about Rustin and his brand of "practical radicalism" is that he was interested in winning, not just being morally right.

Ask most Americans what they think of “radicals” and you’ll hear skepticism. Ask them about “practical radicals,” and you might get a chuckle. Surely practical people don’t try to change society in dramatic ways?

A new film and books about Bayard Rustin, an organizer and strategist in civil rights, peace, and economic justice movements, bring needed attention to the crucial, hidden tradition of practical radicalism that we desperately need to recover.

Practical radicals are responsible for much of the progress we have made over the centuries, and they are our best hope for addressing growing crises of democracy, climate change, and inequality today.

Rustin is best known as the architect of the famous 1963 March on Washington where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. But Rustin spent decades before and after that pivotal event organizing for fundamental changes in American society.

He was a radical who sought an end to racism, war, and poverty. He was motivated by his Quaker faith, his training in nonviolence, pacifism, and an abiding commitment to social democracy. He was persecuted, jailed, shunned and condemned both for his radical convictions and for being a gay man.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

He had little patience for “moderates” who advised civil rights activists to temper their demands for justice. He was unafraid to take big, unconventional risks to advance the cause of justice.

What’s crucial to understand about Rustin is that he was interested in winning, not just being morally right. That led him to reject not only the cramped visions of centrists, but also the wishful thinking of utopian radicals.

In a 1965 essay, Rustin famously said that his “quarrel with the ‘no-win’ tendency in the civil rights movement (and the reason I have so designated it) parallels my quarrel with the moderates outside the movement. As the latter lack the vision or the will for fundamental change, the former lack a realistic strategy for achieving it. For such a strategy, they substitute militancy. But militancy is a matter of posture and volume, not of effect.”

Rustin’s focus on winning led him to openly challenge other leaders he thought were unrealistic, even if their views were popular. As a friend put it, “wherever he was, he stood at a rakish angle to it.”

This attention to strategy and winning led Rustin to focus on the details — not just calling for a big march, but patiently organizing the buses to get people there and making sure that marchers had peanut butter rather than cheese sandwiches because the latter would spoil in the hot sun.

Rustin was an organizer who trained other leaders, rather than seeking the spotlight himself — the list of people he mentored includes Rev. King.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

His insistence on the importance of an alliance between labor and racial justice movements resonates today.

In this age of performative protest and attention-grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored.

Rustin didn’t emphasize fiery speeches or taking the most outrageous position on an issue. He organized behind the scenes, sweated the details, and patiently built coalitions that could win majority support.

Such an approach will prove crucial to those seeking to defeat authoritarian movements in the U.S. today, which will require patiently organizing voters through individual one-to-one conversations and working with people who we may disagree with about many issues.

We might also learn from Rustin’s view that the opposition’s coalition sometimes needs to be broken apart in order to win. Just as he sought to drive Dixiecrats out of the Democratic Party, today’s pro-democracy movements will need to pry apart segments of a formidable authoritarian coalition.

Rustin was trained by other practical radicals, including A Philip Randolph, the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and AJ Muste, an anti-war activist and labor leader. The practical radical tradition runs deep in American history, including people unknown to most Americans like Ella Baker and Rev. Wyatt Teee Walker in the civil rights tradition, and organizers like William Z. Foster and Fannia Cohn in worker movements.

The tradition is alive today. In our new book, Practical Radicals, we feature the stories and strategies of groups that have won extraordinary victories, including worker movements like the Fight for 15 and a Union, community organizations like Make the Road NY, and international climate groups like 350.org.

But in this age of performative protest and attention grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored. Rustin carried on a proud and humble lineage that has advanced justice and equality. It’s time for practical radicals to take center stage.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Ask most Americans what they think of “radicals” and you’ll hear skepticism. Ask them about “practical radicals,” and you might get a chuckle. Surely practical people don’t try to change society in dramatic ways?

A new film and books about Bayard Rustin, an organizer and strategist in civil rights, peace, and economic justice movements, bring needed attention to the crucial, hidden tradition of practical radicalism that we desperately need to recover.

Practical radicals are responsible for much of the progress we have made over the centuries, and they are our best hope for addressing growing crises of democracy, climate change, and inequality today.

Rustin is best known as the architect of the famous 1963 March on Washington where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. But Rustin spent decades before and after that pivotal event organizing for fundamental changes in American society.

He was a radical who sought an end to racism, war, and poverty. He was motivated by his Quaker faith, his training in nonviolence, pacifism, and an abiding commitment to social democracy. He was persecuted, jailed, shunned and condemned both for his radical convictions and for being a gay man.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

He had little patience for “moderates” who advised civil rights activists to temper their demands for justice. He was unafraid to take big, unconventional risks to advance the cause of justice.

What’s crucial to understand about Rustin is that he was interested in winning, not just being morally right. That led him to reject not only the cramped visions of centrists, but also the wishful thinking of utopian radicals.

In a 1965 essay, Rustin famously said that his “quarrel with the ‘no-win’ tendency in the civil rights movement (and the reason I have so designated it) parallels my quarrel with the moderates outside the movement. As the latter lack the vision or the will for fundamental change, the former lack a realistic strategy for achieving it. For such a strategy, they substitute militancy. But militancy is a matter of posture and volume, not of effect.”

Rustin’s focus on winning led him to openly challenge other leaders he thought were unrealistic, even if their views were popular. As a friend put it, “wherever he was, he stood at a rakish angle to it.”

This attention to strategy and winning led Rustin to focus on the details — not just calling for a big march, but patiently organizing the buses to get people there and making sure that marchers had peanut butter rather than cheese sandwiches because the latter would spoil in the hot sun.

Rustin was an organizer who trained other leaders, rather than seeking the spotlight himself — the list of people he mentored includes Rev. King.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

His insistence on the importance of an alliance between labor and racial justice movements resonates today.

In this age of performative protest and attention-grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored.

Rustin didn’t emphasize fiery speeches or taking the most outrageous position on an issue. He organized behind the scenes, sweated the details, and patiently built coalitions that could win majority support.

Such an approach will prove crucial to those seeking to defeat authoritarian movements in the U.S. today, which will require patiently organizing voters through individual one-to-one conversations and working with people who we may disagree with about many issues.

We might also learn from Rustin’s view that the opposition’s coalition sometimes needs to be broken apart in order to win. Just as he sought to drive Dixiecrats out of the Democratic Party, today’s pro-democracy movements will need to pry apart segments of a formidable authoritarian coalition.

Rustin was trained by other practical radicals, including A Philip Randolph, the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and AJ Muste, an anti-war activist and labor leader. The practical radical tradition runs deep in American history, including people unknown to most Americans like Ella Baker and Rev. Wyatt Teee Walker in the civil rights tradition, and organizers like William Z. Foster and Fannia Cohn in worker movements.

The tradition is alive today. In our new book, Practical Radicals, we feature the stories and strategies of groups that have won extraordinary victories, including worker movements like the Fight for 15 and a Union, community organizations like Make the Road NY, and international climate groups like 350.org.

But in this age of performative protest and attention grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored. Rustin carried on a proud and humble lineage that has advanced justice and equality. It’s time for practical radicals to take center stage.

Ask most Americans what they think of “radicals” and you’ll hear skepticism. Ask them about “practical radicals,” and you might get a chuckle. Surely practical people don’t try to change society in dramatic ways?

A new film and books about Bayard Rustin, an organizer and strategist in civil rights, peace, and economic justice movements, bring needed attention to the crucial, hidden tradition of practical radicalism that we desperately need to recover.

Practical radicals are responsible for much of the progress we have made over the centuries, and they are our best hope for addressing growing crises of democracy, climate change, and inequality today.

Rustin is best known as the architect of the famous 1963 March on Washington where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. But Rustin spent decades before and after that pivotal event organizing for fundamental changes in American society.

He was a radical who sought an end to racism, war, and poverty. He was motivated by his Quaker faith, his training in nonviolence, pacifism, and an abiding commitment to social democracy. He was persecuted, jailed, shunned and condemned both for his radical convictions and for being a gay man.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

He had little patience for “moderates” who advised civil rights activists to temper their demands for justice. He was unafraid to take big, unconventional risks to advance the cause of justice.

What’s crucial to understand about Rustin is that he was interested in winning, not just being morally right. That led him to reject not only the cramped visions of centrists, but also the wishful thinking of utopian radicals.

In a 1965 essay, Rustin famously said that his “quarrel with the ‘no-win’ tendency in the civil rights movement (and the reason I have so designated it) parallels my quarrel with the moderates outside the movement. As the latter lack the vision or the will for fundamental change, the former lack a realistic strategy for achieving it. For such a strategy, they substitute militancy. But militancy is a matter of posture and volume, not of effect.”

Rustin’s focus on winning led him to openly challenge other leaders he thought were unrealistic, even if their views were popular. As a friend put it, “wherever he was, he stood at a rakish angle to it.”

This attention to strategy and winning led Rustin to focus on the details — not just calling for a big march, but patiently organizing the buses to get people there and making sure that marchers had peanut butter rather than cheese sandwiches because the latter would spoil in the hot sun.

Rustin was an organizer who trained other leaders, rather than seeking the spotlight himself — the list of people he mentored includes Rev. King.

Rustin emphasized the need for coalitions — understanding that the path to victory depended on uniting a majority comprised of many minorities. Building such coalitions is difficult work that requires compromises and patience.

His insistence on the importance of an alliance between labor and racial justice movements resonates today.

In this age of performative protest and attention-grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored.

Rustin didn’t emphasize fiery speeches or taking the most outrageous position on an issue. He organized behind the scenes, sweated the details, and patiently built coalitions that could win majority support.

Such an approach will prove crucial to those seeking to defeat authoritarian movements in the U.S. today, which will require patiently organizing voters through individual one-to-one conversations and working with people who we may disagree with about many issues.

We might also learn from Rustin’s view that the opposition’s coalition sometimes needs to be broken apart in order to win. Just as he sought to drive Dixiecrats out of the Democratic Party, today’s pro-democracy movements will need to pry apart segments of a formidable authoritarian coalition.

Rustin was trained by other practical radicals, including A Philip Randolph, the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and AJ Muste, an anti-war activist and labor leader. The practical radical tradition runs deep in American history, including people unknown to most Americans like Ella Baker and Rev. Wyatt Teee Walker in the civil rights tradition, and organizers like William Z. Foster and Fannia Cohn in worker movements.

The tradition is alive today. In our new book, Practical Radicals, we feature the stories and strategies of groups that have won extraordinary victories, including worker movements like the Fight for 15 and a Union, community organizations like Make the Road NY, and international climate groups like 350.org.

But in this age of performative protest and attention grabbing social media, the crucial role of practical radicals in actually achieving and not just talking about social change often gets ignored. Rustin carried on a proud and humble lineage that has advanced justice and equality. It’s time for practical radicals to take center stage.