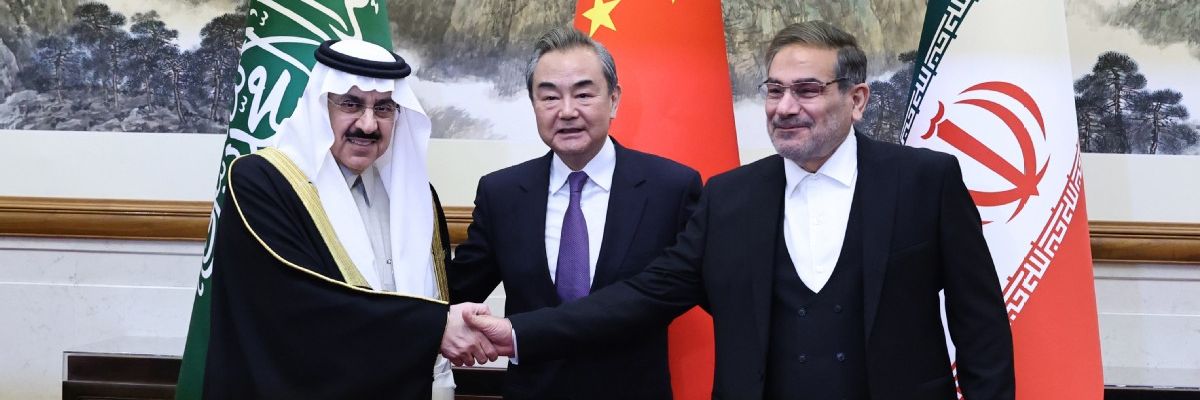

A photo Beijing released on March 6 of Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a seismic shock in Washington. There was the Secretary-General of the Chinese Communist Party standing between Ali Shamkhani, the secretary of Iran’s National Security Council, and Saudi National Security Adviser Musaad bin Mohammed al-Aiban. They were awkwardly shaking hands on an agreement to reestablish mutual diplomatic ties. That picture should have brought to mind a 1993 photo of President Bill Clinton hosting Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization chief Yasser Arafat on the White House lawn as they agreed to the Oslo Accords. And that long-gone moment was itself an after-effect of the halo of invincibility the United States had gained in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the overwhelming American victory in the 1991 Gulf War.

This time around, the U.S. had been cut out of the picture, a sea change reflecting not just Chinese initiatives but Washington’s incompetence, arrogance, and double-dealing in the subsequent three decades in the Middle East. An aftershock came in early May as concerns gripped Congress about the covert construction of a Chinese naval base in the United Arab Emirates, a U.S. ally hosting thousands of American troops. The Abu Dhabi facility would be an add-on to the small base at Djibouti on the east coast of Africa used by the People’s Liberation Army-Navy for combating piracy, evacuating noncombatants from conflict zones, and perhaps regional espionage.

China’s interest in cooling off tensions between the Iranian ayatollahs and the Saudi monarchy arose, however, not from any military ambitions in the region but because it imports significant amounts of oil from both countries. Another impetus was undoubtedly President Xi’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, that aims to expand Eurasia’s overland and maritime economic infrastructure for a vast growth of regional trade—with China, of course, at its heart. That country has already invested billions in a China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and in developing the Pakistani Arabian seaport of Gwadar to facilitate the transmission of Gulf oil to its northwestern provinces.

This time around, the U.S. had been cut out of the picture.

Having Iran and Saudi Arabia on a war footing endangered Chinese economic interests. Remember that, in September 2019, an Iran proxy or Iran itself launched a drone attack on the massive refinery complex at al-Abqaiq, briefly knocking out 5 million barrels a day of Saudi capacity. That country now exports a staggering 1.7 million barrels of petroleum daily to China, and future drone strikes (or similar events) threaten those supplies. China is also believed to receive as much as 1.2 million barrels a day from Iran, though it does so surreptitiously because of U.S. sanctions. In December 2022, when nationwide protests forced the end of Xi’s no-Covid lockdown measures, that country’s appetite for petroleum was once again unleashed, with demand already up 22% over 2022.

So, any further instability in the Gulf is the last thing the Chinese Communist Party needs right now. Of course, China is also a global leader in the transition away from petroleum-fueled vehicles, which will eventually make the Middle East far less important to Beijing. That day, however, is still 15 to 30 years away.

Things Could Have Been Different

China’s interest in bringing to an end the Iranian-Saudi cold war, which constantly threatened to turn hotter, is clear enough, but why did those two countries choose such a diplomatic channel? After all, the United States still styles itself the “indispensable nation.” If that phrase ever had much meaning, however, American indispensability is now visibly in decline, thanks to blunders like allowing Israeli right-wingers to cancel the Oslo peace process, the launching of an illegal invasion of and war in Iraq in 2003, and the grotesque Trumpian mishandling of Iran. Distant as it may be from Europe, Tehran might nonetheless have been brought into NATO’s sphere of influence, something President Barack Obama spent enormous political capital trying to achieve. Instead, then-President Donald Trump pushed it directly into the arms of Vladimir Putin’s Russian Federation and Xi’s China.

Things could indeed have been different. With the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal, brokered by the Obama administration, all practical pathways for Iran to build nuclear weapons were closed off. It’s also true that Iran’s ayatollahs have long insisted they don’t want a weapon of mass destruction that, if used, would indiscriminately kill potentially vast numbers of non-combatants, something incompatible with the ethics of Islamic law.

Whether one believes that country’s clerical leaders or not, the JCPOA made the question moot, since it imposed severe restrictions on the number of centrifuges Iran could operate, the level to which it could enrich uranium for its nuclear plant at Bushehr, the amount of enriched uranium it could stockpile, and the kinds of nuclear plants it could build. According to the inspectors at the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency, Iran faithfully implemented its obligations through 2018 and—consider this an irony of our Trumpian times—for such compliance it would be punished by Washington.

Tehran could have been pulled inexorably into the Western orbit via increasing dependence on North Atlantic trade deals, but it was not to be.

Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei only permitted President Hassan Rouhani to sign that somewhat mortifying treaty with the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council in return for promised relief from Washington’s sanctions (that they never got). In early 2016, the Security Council did indeed remove its own 2006 sanctions on Iran. That, however, proved a meaningless gesture because by then Congress, deploying the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, had slapped unilateral American sanctions on Iran, and, even in the wake of the nuclear deal, congressional Republicans refused to lift them. They even nixed a $25 billion deal that would have allowed Iran to buy civilian passenger jets from Boeing.

Worse yet, such sanctions were designed to punish third parties that contravened them. French firms like Renault and TotalEnergies were eager to jump into the Iranian market but feared reprisals. The U.S. had, after all, fined French bank BNP $8.7 billion for skirting those sanctions, and no European corporation wanted a dose of that kind of grief. In essence, congressional Republicans and the Trump administration kept Iran under such severe sanctions even though it had lived up to its side of the bargain, while Iranian entrepreneurs eagerly looked forward to doing business with Europe and the United States. In short, Tehran could have been pulled inexorably into the Western orbit via increasing dependence on North Atlantic trade deals, but it was not to be.

And keep in mind that Israeli Prime Minister (then as now) Benjamin Netanyahu had lobbied hard against the JCPOA, even going over President Obama’s head in an unprecedented fashion to encourage Congress to nix the deal. That effort to play spoiler failed—until, in May 2018, President Trump simply tore up the treaty. Netanyahu was caught on tape boasting that he had convinced the gullible Trump to take that step. Although the Israeli right wing insisted that its greatest concern was an Iranian nuclear warhead, it sure didn’t act that way. Sabotaging the 2015 deal actually freed that country from all constraints. Netanyahu and like-minded Israeli politicians were, it seems, upset that the JCPOA only addressed Iran’s civilian nuclear enrichment program and didn’t mandate a rollback of Iranian influence in Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, which they apparently believed to be the real threat.

Trump went on to impose what amounted to a financial and trade embargo on Iran. In its wake, trading with that country became an increasingly risky proposition. By May 2019, Trump had succeeded handsomely by his own standards (and those of Netanyahu). He had managed to reduce Iran’s oil exports from 2.5 million barrels a day to as little as 200,000 barrels a day. That country’s leadership nonetheless continued to conform to the requirements of the JCPOA until mid-2019, after which they began flaunting its provisions. Iran has now produced highly enriched uranium and is much closer to being capable of making nuclear weapons than ever before, though it still has no military nuclear program and the ayatollahs continue to deny that they want such weaponry.

In reality, Trump’s “maximum pressure campaign” did anything but destroy Tehran’s influence in the region. In fact, if anything, in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq the power of the ayatollahs was only strengthened.

After a while, Iran also found ways to smuggle its petroleum to China, where it was sold to small private refineries that operated solely for the domestic market. Since those firms had no international presence or assets and didn’t deal in dollars, the Treasury Department had no way of moving against them. In this fashion, President Trump and congressional Republicans ensured that Iran would become deeply dependent on China for its very economic survival—and so also ensured the increasing significance of that rising power in the Middle East.

The Saudi Reversal

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, oil prices spiked, benefiting the Iranian government. The Biden administration then imposed the kind of maximum-pressure sanctions on the Russian Federation that Trump had levied against Iran. Unsurprisingly, a new Axis of the Sanctioned has now formed, with Iran and Russia exploring trade and arms deals and Iran allegedly providing drones to Moscow for its war effort in Ukraine.

As for Saudi Arabia, its de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, recently seemed to get a better set of advisers. In March 2015, he had launched a ruinous and devastating war in neighboring Yemen after the Zaydi Shiite “Helpers of God,” or Houthi rebels, took over the populous north of that country. Since the Saudis were primarily deploying air power against a guerrilla force, their campaign was bound to fail. The Saudi leadership then blamed the rise and resilience of the Houthis on the Iranians. While Iran had indeed provided some money and smuggled some weapons to the Helpers of God, they were a local movement with a long set of grievances against the Saudis. Eight years later, the war has sputtered to a devastating stalemate.

The Saudis had also attempted to counter Iranian influence elsewhere in the Arab world, intervening in the Syrian civil war on the side of fundamentalist Salafi rebels against the government of autocrat Bashar al-Assad. In 2013, Lebanon’s Shiite Hezbollah militia joined the fray in support of al-Assad, and, in 2015, Russia committed air power there to ensure the rebels’ defeat. China had also backed al-Assad (though not militarily) and played a quiet role in the post-war reconstruction of the country. As part of that recent China-brokered agreement to reduce tensions with Iran and its regional allies, Saudi Arabia just spearheaded a decision to return the al-Assad government to membership in the Arab League (from which it had been expelled in 2011 at the height of the Arab Spring revolts).

As for Saudi Arabia, its de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, recently seemed to get a better set of advisers.

By late 2019, in the wake of that drone attack on the Abqaiq refineries, it was already clear that Bin Salman had lost his regional contest with Iran, and Saudi Arabia began to seek some way out. Among other things, the Saudis reached out to the Iraqi prime minister of that moment, Adil Abdul Mahdi, asking for his help as a mediator with the Iranians. He, in turn, invited General Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Jerusalem Brigade of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, to Baghdad to consider a new relationship with the House of Saud.

As few will forget, on January 3, 2020, Soleimani flew to Iraq on a civilian airliner only to be assassinated by an American drone strike at Baghdad International Airport on the orders of President Trump, who claimed he was coming to kill Americans. Did Trump want to forestall a rapprochement with the Saudis? After all, marshaling that country and other Gulf states into an anti-Iranian alliance with Israel had been at the heart of his son-in-law Jared Kushner’s “Abraham Accords.”

The Rise of China, the Fall of America

Washington is now the skunk at the diplomats’ party. The Iranians were never likely to trust the Americans as mediators. The Saudis must have feared telling them about their negotiations lest the equivalent of another Hellfire missile be unleashed. As 2022 ended, President Xi actually visited the Saudi capital Riyadh, where relations with Iran were evidently a topic of conversation. This February, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi traveled to Beijing by which time, according to the Chinese foreign ministry, President Xi had developed a personal commitment to mediating between the two Gulf rivals. Now, a rising China is offering to launch other Middle Eastern mediation efforts, while complaining “that some large countries outside the region” were causing “long-term instability in the Middle East” out of “self-interest.”

China’s new prominence as a peacemaker may soon extend to conflicts like the ones in Yemen and Sudan. As the rising power on this planet with its eye on Eurasia, the Middle East, and Africa, Beijing is clearly eager to have any conflicts that could interfere with its Belt and Road Initiative resolved as peaceably as possible.

Washington is now the skunk at the diplomats’ party.

Although China is on the cusp of having three aircraft carrier battle groups, they continue to operate close to home and American fears about a Chinese military presence in the Middle East are, so far, without substance.

Where two sides are tired of conflict, as was true with Saudi Arabia and Iran, Beijing is clearly now ready to play the role of the honest broker. Its remarkable diplomatic feat of restoring relations between those countries, however, reflects less its position as a rising Middle Eastern power than the startling decline of American regional credibility after three decades of false promises (Oslo), debacles (Iraq), and capricious policy-making that, in retrospect, appears to have relied on nothing more substantial than a set of cynical imperial divide-and-rule ploys that are now so been-there, done-that.