An aerial view of Jackson, Kentucky shows homes submerged under flood waters from the North Fork of the Kentucky River on July 28, 2022.

The Climate Crisis Is Also an Insurance Crisis

As another summer Danger Season gets underway, it’s time for policymakers and regulators to get serious about real solutions to address the insurance crisis.

If you own a home in a flood-prone community or in a wildfire-prone area, you’ve probably seen your flood or home insurance rates go up in the last year, or are worried that they soon will. You may even worry you’ll be dropped entirely by your insurance provider.

If you’re a renter, you too may be feeling the pinch as rising insurance premiums are also hurting the rental market for affordable housing. Accelerating risks from climate change are colliding with shortcomings in insurance markets—such as a lack of transparent information and affordability provisions—to create a perfect storm for people and communities on the front lines of floods, droughts, and wildfires. As climate scientist Michael Mann has said, “Uninsurability is the first stage of uninhabitability.”

An Insurance Market in Crisis

Last year, I wrote about the worsening risks of climate change for insurance, and since then the challenges have only grown and spread to more people and places. As another summer Danger Season gets underway with extreme floods in Texas and Florida, wildfires in California, and an above-average hurricane season predicted, it’s time for policymakers and regulators to get serious about real solutions to address the insurance crisis.

Having access to affordable home insurance is crucial to helping people safeguard what is likely to be their single biggest asset, and in turn protect their sense of well-being and stability. But we’ve all seen the news headlines of insurance companies withdrawing from states or announcing that they will stop issuing new property insurance policies, including in California, Florida, and Louisiana. Data show that insurers in many states are facing growing losses in the homeowner’s insurance part of their business, in large part due to the escalating impacts of extreme weather and climate.

Recent news stories also indicate that rapidly rising insurance costs are becoming a pain point for landlords and developers of affordable housing. Survey data show that this is quickly escalating into a crisis for the rental market for affordable housing. This has significant equity implications, given our nation’s long-standing under-investment in affordable housing and the huge housing affordability crisis we are already in.

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection.

Egregiously, even as climate-driven disasters leave communities reeling, private insurers are continuing to underwrite insurance for the expansion of massive new fossil fuel projects that are directly responsible for fueling the climate crisis—and show no sign of withdrawing from these markets!

As the global insurance market reacts to a worldwide increase in costly extreme disasters, major reinsurance companies (which provide insurance for primary customer-facing insurance companies) are also raising rates. And insurers are in turn trying to pass those rate hikes through to consumers. Rate hikes can be significant from one year to the next, an unexpected shock to many homeowners, especially those on low or fixed incomes. While the changes are most acute in highly exposed states (such as Florida), climate risks are now so widespread that the increase in insurance premiums is spilling into the broader market, even in places less exposed, and could also affect the mortgage market and taxpayers more broadly. These larger macroeconomic risks were highlighted in a recent National Academy of Sciences (NAS) workshop during a panel I chaired on insurance and climate risks.

How Climate Change Is Making Things Worse

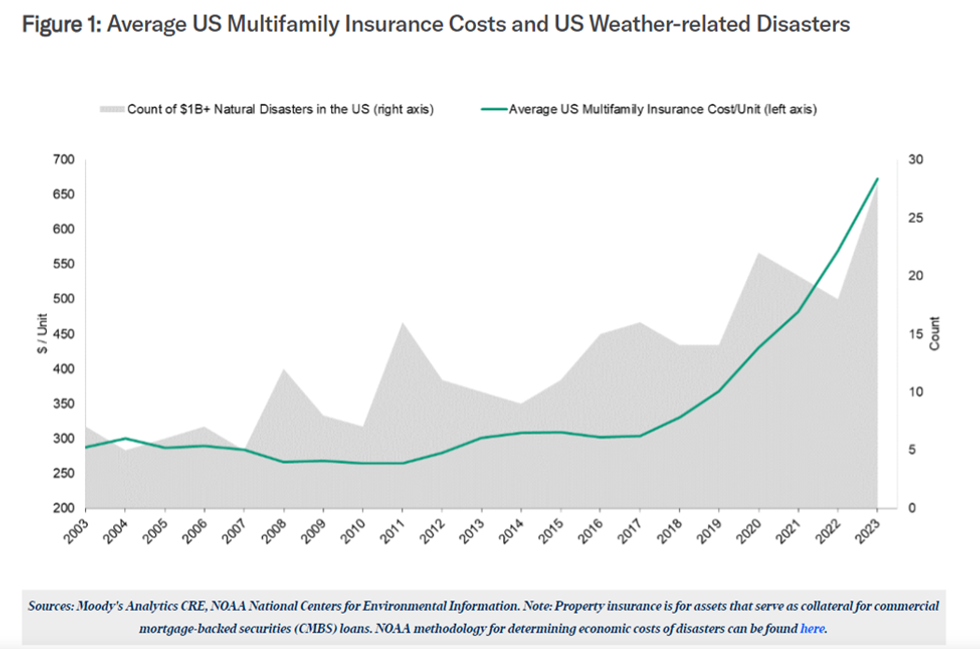

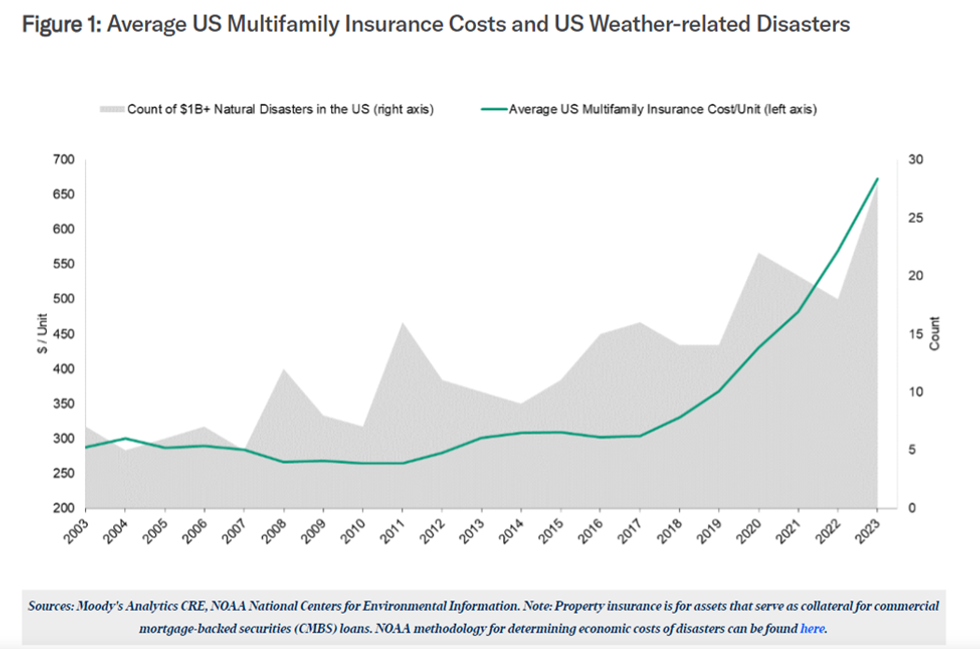

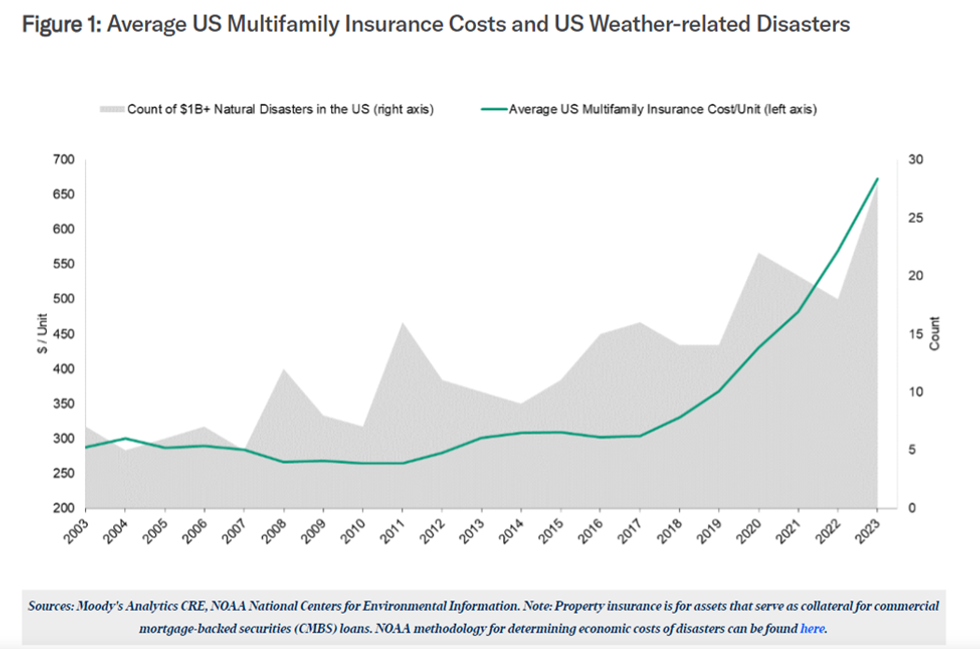

The fossil fuel-driven increase in global average temperatures has induced a significant rise in extreme weather and climate events including extreme heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, and flooding. Last year the U.S. experienced a record-breaking 28 extreme weather and climate disasters whose costs each surpassed $1 billion. As a recent report from Moody’s shows, insurance costs have also been rising as disasters mount (see graph below). Many of these disasters bear the fingerprints of climate change. Continued development in high-risk areas is also increasing costs when disasters do strike. Insured losses are a big part of the costs measured but uninsured losses and incalculable losses—like loss of lives, and mental health impacts—are also mounting.

With the relentless rise in global average temperatures continuing, unfortunately, we can expect the trend of extreme weather and climate related disasters to continue. Today’s challenges in the insurance markets are likely just a taste of what’s to come.

Insurers of Last Resort

Florida has seen a number of private insurance companies go into receivership in the last few years, and Citizens Property Insurance, the state taxpayer-backed insurer of last resort, has taken on more policies as private insurers go out of business. The latest data show another uptick in Citizens policies in advance of what is expected to be an active hurricane season.

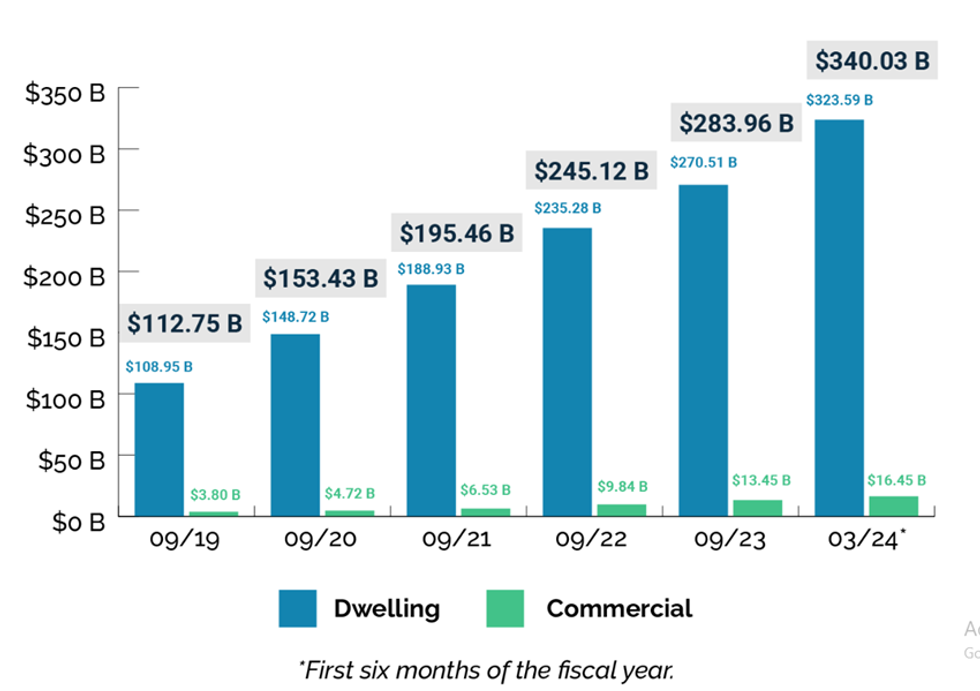

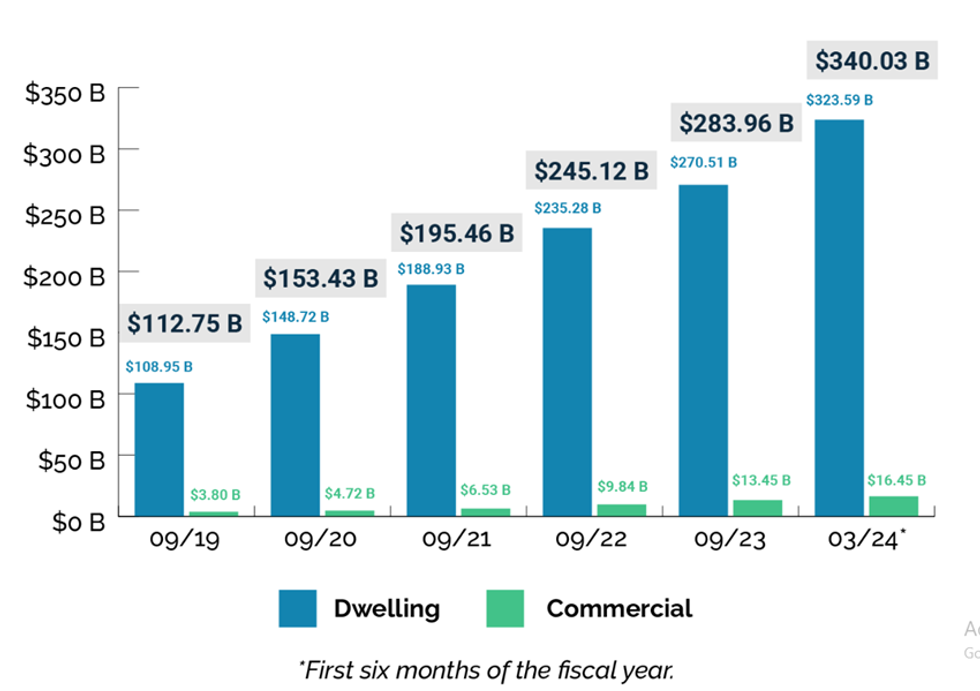

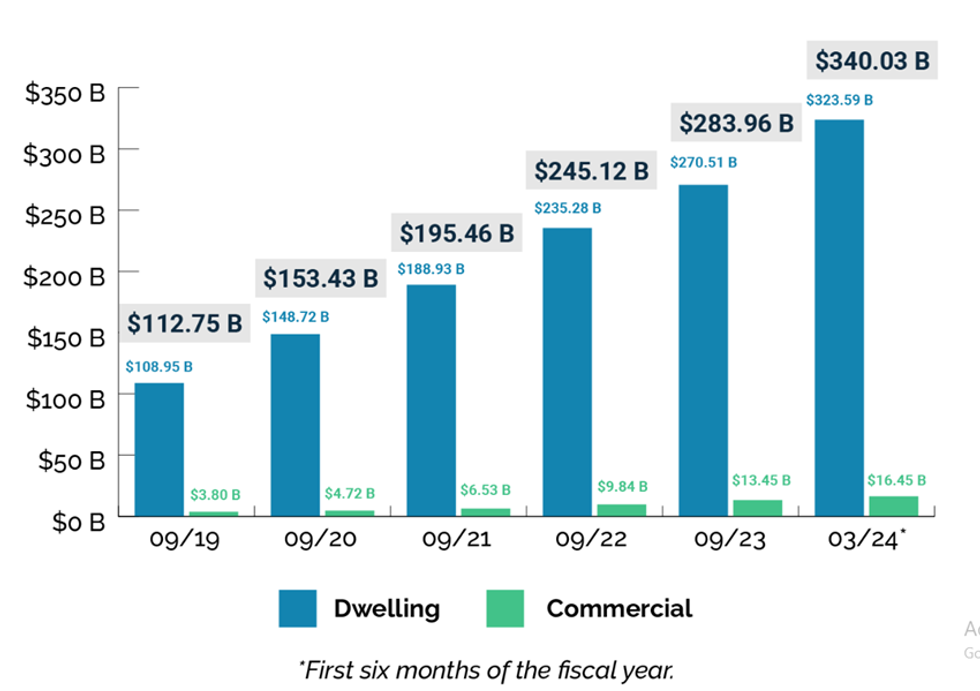

This trend of more and more policyholders moving from the private homeowners insurance market to state-backed insurance of “last resort”—called Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plans—is also happening in other highly exposed states like California, Louisiana, and North Carolina. In California, the FAIR plan’s exposure to loss is getting increasingly unsustainable, putting it at risk of insolvency. Data from CA FAIR Plan show that “as of March 2024 (partial fiscal year), the FAIR Plan’s total exposure is $340 billion, reflecting a 20% year-over-year increase.” (See chart below)

A report from Milliman shows that:

- Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corporation grew by +277% between 2017 and 2022, resulting in $423 billion of in-force Total Insured Value (TIV) at the end of 2022.

- The Louisiana Citizens Property Insurance Corporation experienced the highest overall growth over the period, +414% resulting in $41 billion of 2022 in-force TIV.

- The Washington FAIR Plan (WA FAIR Plan) showed a five-year exposure increase of +226%, with about $70 million in TIV at the end of 2022.

Turmoil in Public and Private Insurance Markets

In both the public and private insurance markets, climate-driven risks are creating turmoil. The private homeowner’s insurance market—which covers insurance against wildfires—has seen major insurers like State Farm and Allstate cease to offer new insurance policies in California, and rates for others going up (as Travelers Insurance announced recently). Similar actions are also happening in parts of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, which are also severely wildfire prone.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), administered by FEMA, is the primary source of flood insurance that isn’t covered by typical homeowners insurance. FEMA has also recently implemented changes to NFIP rates, with the intended aim of better reflecting current flood risk under the Risk Rating 2.0 program. Some of the steepest increases have come in states like Louisiana which are highly exposed to flooding; 10 states have sued FEMA to block the changes. And because Congress has long failed to enact affordability provisions—which the NAS, FEMA, and others have called for—these rate increases are causing significant hardship to many people with the least resources.

Much of the nation’s housing stock is also likely under-insured against flooding because only homes in FEMA’s high flood-risk zones with federally backed mortgages are required to carry flood insurance—and that insurance is likely inadequate given what the science shows about accelerating coastal flood risks, which are not captured by current FEMA flood maps.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has repeatedly called out the taxpayer-backed flood insurance program in its “High Risk Series” of reports on areas of exposure for the federal government. In its 2023 report, the GAO says: “The federal government needs to take additional actions to improve the long-term resilience of insured structures and crops. It also needs to address structural weaknesses in its insurance programs.”

The Role of Policymakers and Regulators

Last year, Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) launched an investigation into the climate-driven insurance crisis and sent letters to 41 insurance companies requesting more information on how they are addressing this problem. Earlier this month, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing on how climate change is challenging insurance markets. The hearing featured wrenching testimony from Deborah Wood, a Florida resident who has had to sell her home because of the unaffordability of insurance. Non-coastal states were also represented as Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) admitted in his opening statement that “Iowa had six property and casualty companies pull out of insuring Iowans.”

Private insurance—the category into which most homeowners’ insurance falls—is regulated at the state level by state insurance commissioners who are supposed to look out for the interests of consumers. However, their role can be different in different states, and even in the states with strong oversight, the power of regulators is somewhat limited. For example, California has tried to implement a moratorium on rate increases in the past, but that has only been possible on a temporary basis as wildfire impacts grow. Ultimately, some insurers are making the decision that it is unprofitable to operate in certain markets and are choosing to exit them.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners have jointly issued a call for data to better understand the impacts of climate-driven risks on the homeowners insurance market, with a focus on affordability and availability of insurance. The first tranche of data is expected this month; however, some of the most climate-exposed states—including Florida, Texas, and Louisiana—will likely choose not to participate.

Having access to the latest data and science to understand not just today’s risks, but how those risks will change over the lifetime of a property, is crucial. Congress and regulators need to ensure more transparency in the insurance market on how companies are evaluating risks as they make decisions about premiums. There also needs to be better information on what kinds of incentives companies are providing for adaptation measures that would help reduce risks. Transparency will also help regulators look out for the interests of consumers and ensure that companies are not using climate risks as a cover for dropping less profitable lines of business—for example in less wealthy communities.

The Limits of Insurance—and the Need for Just Resilience Policies

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection. Former California insurance commissioner Dave Jones has said, “I believe we’re marching toward an uninsurable future,” in many places. That will have significant consequences for the many people, homes, and the trillions of dollars of infrastructure assets in harm’s way, and we need to plan for it now.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones. The nation must scale up resources for climate resilience and ensure they are reaching communities in a just and equitable way. Funding for safe, affordable, and climate-resilient housing must be expanded. Some places just won’t be possible to insure indefinitely, but people need options for fair pathways away from the risks.

And we’ve got to sharply curtail heat-trapping emissions and phase out fossil fuels to limit catastrophic climate impacts and help keep people safe in an increasingly perilous world.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

If you own a home in a flood-prone community or in a wildfire-prone area, you’ve probably seen your flood or home insurance rates go up in the last year, or are worried that they soon will. You may even worry you’ll be dropped entirely by your insurance provider.

If you’re a renter, you too may be feeling the pinch as rising insurance premiums are also hurting the rental market for affordable housing. Accelerating risks from climate change are colliding with shortcomings in insurance markets—such as a lack of transparent information and affordability provisions—to create a perfect storm for people and communities on the front lines of floods, droughts, and wildfires. As climate scientist Michael Mann has said, “Uninsurability is the first stage of uninhabitability.”

An Insurance Market in Crisis

Last year, I wrote about the worsening risks of climate change for insurance, and since then the challenges have only grown and spread to more people and places. As another summer Danger Season gets underway with extreme floods in Texas and Florida, wildfires in California, and an above-average hurricane season predicted, it’s time for policymakers and regulators to get serious about real solutions to address the insurance crisis.

Having access to affordable home insurance is crucial to helping people safeguard what is likely to be their single biggest asset, and in turn protect their sense of well-being and stability. But we’ve all seen the news headlines of insurance companies withdrawing from states or announcing that they will stop issuing new property insurance policies, including in California, Florida, and Louisiana. Data show that insurers in many states are facing growing losses in the homeowner’s insurance part of their business, in large part due to the escalating impacts of extreme weather and climate.

Recent news stories also indicate that rapidly rising insurance costs are becoming a pain point for landlords and developers of affordable housing. Survey data show that this is quickly escalating into a crisis for the rental market for affordable housing. This has significant equity implications, given our nation’s long-standing under-investment in affordable housing and the huge housing affordability crisis we are already in.

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection.

Egregiously, even as climate-driven disasters leave communities reeling, private insurers are continuing to underwrite insurance for the expansion of massive new fossil fuel projects that are directly responsible for fueling the climate crisis—and show no sign of withdrawing from these markets!

As the global insurance market reacts to a worldwide increase in costly extreme disasters, major reinsurance companies (which provide insurance for primary customer-facing insurance companies) are also raising rates. And insurers are in turn trying to pass those rate hikes through to consumers. Rate hikes can be significant from one year to the next, an unexpected shock to many homeowners, especially those on low or fixed incomes. While the changes are most acute in highly exposed states (such as Florida), climate risks are now so widespread that the increase in insurance premiums is spilling into the broader market, even in places less exposed, and could also affect the mortgage market and taxpayers more broadly. These larger macroeconomic risks were highlighted in a recent National Academy of Sciences (NAS) workshop during a panel I chaired on insurance and climate risks.

How Climate Change Is Making Things Worse

The fossil fuel-driven increase in global average temperatures has induced a significant rise in extreme weather and climate events including extreme heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, and flooding. Last year the U.S. experienced a record-breaking 28 extreme weather and climate disasters whose costs each surpassed $1 billion. As a recent report from Moody’s shows, insurance costs have also been rising as disasters mount (see graph below). Many of these disasters bear the fingerprints of climate change. Continued development in high-risk areas is also increasing costs when disasters do strike. Insured losses are a big part of the costs measured but uninsured losses and incalculable losses—like loss of lives, and mental health impacts—are also mounting.

With the relentless rise in global average temperatures continuing, unfortunately, we can expect the trend of extreme weather and climate related disasters to continue. Today’s challenges in the insurance markets are likely just a taste of what’s to come.

Insurers of Last Resort

Florida has seen a number of private insurance companies go into receivership in the last few years, and Citizens Property Insurance, the state taxpayer-backed insurer of last resort, has taken on more policies as private insurers go out of business. The latest data show another uptick in Citizens policies in advance of what is expected to be an active hurricane season.

This trend of more and more policyholders moving from the private homeowners insurance market to state-backed insurance of “last resort”—called Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plans—is also happening in other highly exposed states like California, Louisiana, and North Carolina. In California, the FAIR plan’s exposure to loss is getting increasingly unsustainable, putting it at risk of insolvency. Data from CA FAIR Plan show that “as of March 2024 (partial fiscal year), the FAIR Plan’s total exposure is $340 billion, reflecting a 20% year-over-year increase.” (See chart below)

A report from Milliman shows that:

- Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corporation grew by +277% between 2017 and 2022, resulting in $423 billion of in-force Total Insured Value (TIV) at the end of 2022.

- The Louisiana Citizens Property Insurance Corporation experienced the highest overall growth over the period, +414% resulting in $41 billion of 2022 in-force TIV.

- The Washington FAIR Plan (WA FAIR Plan) showed a five-year exposure increase of +226%, with about $70 million in TIV at the end of 2022.

Turmoil in Public and Private Insurance Markets

In both the public and private insurance markets, climate-driven risks are creating turmoil. The private homeowner’s insurance market—which covers insurance against wildfires—has seen major insurers like State Farm and Allstate cease to offer new insurance policies in California, and rates for others going up (as Travelers Insurance announced recently). Similar actions are also happening in parts of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, which are also severely wildfire prone.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), administered by FEMA, is the primary source of flood insurance that isn’t covered by typical homeowners insurance. FEMA has also recently implemented changes to NFIP rates, with the intended aim of better reflecting current flood risk under the Risk Rating 2.0 program. Some of the steepest increases have come in states like Louisiana which are highly exposed to flooding; 10 states have sued FEMA to block the changes. And because Congress has long failed to enact affordability provisions—which the NAS, FEMA, and others have called for—these rate increases are causing significant hardship to many people with the least resources.

Much of the nation’s housing stock is also likely under-insured against flooding because only homes in FEMA’s high flood-risk zones with federally backed mortgages are required to carry flood insurance—and that insurance is likely inadequate given what the science shows about accelerating coastal flood risks, which are not captured by current FEMA flood maps.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has repeatedly called out the taxpayer-backed flood insurance program in its “High Risk Series” of reports on areas of exposure for the federal government. In its 2023 report, the GAO says: “The federal government needs to take additional actions to improve the long-term resilience of insured structures and crops. It also needs to address structural weaknesses in its insurance programs.”

The Role of Policymakers and Regulators

Last year, Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) launched an investigation into the climate-driven insurance crisis and sent letters to 41 insurance companies requesting more information on how they are addressing this problem. Earlier this month, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing on how climate change is challenging insurance markets. The hearing featured wrenching testimony from Deborah Wood, a Florida resident who has had to sell her home because of the unaffordability of insurance. Non-coastal states were also represented as Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) admitted in his opening statement that “Iowa had six property and casualty companies pull out of insuring Iowans.”

Private insurance—the category into which most homeowners’ insurance falls—is regulated at the state level by state insurance commissioners who are supposed to look out for the interests of consumers. However, their role can be different in different states, and even in the states with strong oversight, the power of regulators is somewhat limited. For example, California has tried to implement a moratorium on rate increases in the past, but that has only been possible on a temporary basis as wildfire impacts grow. Ultimately, some insurers are making the decision that it is unprofitable to operate in certain markets and are choosing to exit them.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners have jointly issued a call for data to better understand the impacts of climate-driven risks on the homeowners insurance market, with a focus on affordability and availability of insurance. The first tranche of data is expected this month; however, some of the most climate-exposed states—including Florida, Texas, and Louisiana—will likely choose not to participate.

Having access to the latest data and science to understand not just today’s risks, but how those risks will change over the lifetime of a property, is crucial. Congress and regulators need to ensure more transparency in the insurance market on how companies are evaluating risks as they make decisions about premiums. There also needs to be better information on what kinds of incentives companies are providing for adaptation measures that would help reduce risks. Transparency will also help regulators look out for the interests of consumers and ensure that companies are not using climate risks as a cover for dropping less profitable lines of business—for example in less wealthy communities.

The Limits of Insurance—and the Need for Just Resilience Policies

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection. Former California insurance commissioner Dave Jones has said, “I believe we’re marching toward an uninsurable future,” in many places. That will have significant consequences for the many people, homes, and the trillions of dollars of infrastructure assets in harm’s way, and we need to plan for it now.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones. The nation must scale up resources for climate resilience and ensure they are reaching communities in a just and equitable way. Funding for safe, affordable, and climate-resilient housing must be expanded. Some places just won’t be possible to insure indefinitely, but people need options for fair pathways away from the risks.

And we’ve got to sharply curtail heat-trapping emissions and phase out fossil fuels to limit catastrophic climate impacts and help keep people safe in an increasingly perilous world.

- The Insurance Industry Can Doom Us, or Help Save Us All ›

- As Insurers Cut Coverage Due to Climate Disasters, Senators Probe Continued Backing of Fossil Fuels ›

- Activists to Insurance Giants: 'End Your Support for Oil and Gas Now' ›

- US Insurance Giants Ditching Homeowners, But Still Underwriting Climate-Killing Coal Industry ›

- FEMA Limits Building in Flood Plains But 'Still Desperately Needs to Transform' | Common Dreams ›

- Helene's Catastrophic Potential Stokes Fear Amid Florida Insurance Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Insurance Companies Are Not Good Neighbors to Have in a Climate Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- As Planet Heads Toward 2.7°C Rise, Tracker Warns Global Climate Action Has 'Flatlined' | Common Dreams ›

- Congressional Report Warns of Climate Threat to US Insurance, Housing Markets | Common Dreams ›

- Amid LA Inferno, Home Insurers Under Fire for Policy Cancellations | Common Dreams ›

- Climate-Fueled Insurance Cost Hikes Putting American Dream 'Out of Reach' | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Like a Bad Neighbor, State Farm Is There... in California | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | What the Texas Floods Can Teach Us About Disaster Readiness in a Changing Climate | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | It’s Time to Be Honest About What Caused the Texas Floods: Fossil-Fueled Climate Change | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Roll up Your Sleeves for Climate Resilience Summer | Common Dreams ›

- As World Convenes in Brazil, WHO Warns of Dire Health Impacts of Climate Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Property Insurance Is the Canary in the Climate Coal Mine | Common Dreams ›

- Washington Homeowners Sue Big Oil Over Soaring Insurance Costs | Common Dreams ›

If you own a home in a flood-prone community or in a wildfire-prone area, you’ve probably seen your flood or home insurance rates go up in the last year, or are worried that they soon will. You may even worry you’ll be dropped entirely by your insurance provider.

If you’re a renter, you too may be feeling the pinch as rising insurance premiums are also hurting the rental market for affordable housing. Accelerating risks from climate change are colliding with shortcomings in insurance markets—such as a lack of transparent information and affordability provisions—to create a perfect storm for people and communities on the front lines of floods, droughts, and wildfires. As climate scientist Michael Mann has said, “Uninsurability is the first stage of uninhabitability.”

An Insurance Market in Crisis

Last year, I wrote about the worsening risks of climate change for insurance, and since then the challenges have only grown and spread to more people and places. As another summer Danger Season gets underway with extreme floods in Texas and Florida, wildfires in California, and an above-average hurricane season predicted, it’s time for policymakers and regulators to get serious about real solutions to address the insurance crisis.

Having access to affordable home insurance is crucial to helping people safeguard what is likely to be their single biggest asset, and in turn protect their sense of well-being and stability. But we’ve all seen the news headlines of insurance companies withdrawing from states or announcing that they will stop issuing new property insurance policies, including in California, Florida, and Louisiana. Data show that insurers in many states are facing growing losses in the homeowner’s insurance part of their business, in large part due to the escalating impacts of extreme weather and climate.

Recent news stories also indicate that rapidly rising insurance costs are becoming a pain point for landlords and developers of affordable housing. Survey data show that this is quickly escalating into a crisis for the rental market for affordable housing. This has significant equity implications, given our nation’s long-standing under-investment in affordable housing and the huge housing affordability crisis we are already in.

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection.

Egregiously, even as climate-driven disasters leave communities reeling, private insurers are continuing to underwrite insurance for the expansion of massive new fossil fuel projects that are directly responsible for fueling the climate crisis—and show no sign of withdrawing from these markets!

As the global insurance market reacts to a worldwide increase in costly extreme disasters, major reinsurance companies (which provide insurance for primary customer-facing insurance companies) are also raising rates. And insurers are in turn trying to pass those rate hikes through to consumers. Rate hikes can be significant from one year to the next, an unexpected shock to many homeowners, especially those on low or fixed incomes. While the changes are most acute in highly exposed states (such as Florida), climate risks are now so widespread that the increase in insurance premiums is spilling into the broader market, even in places less exposed, and could also affect the mortgage market and taxpayers more broadly. These larger macroeconomic risks were highlighted in a recent National Academy of Sciences (NAS) workshop during a panel I chaired on insurance and climate risks.

How Climate Change Is Making Things Worse

The fossil fuel-driven increase in global average temperatures has induced a significant rise in extreme weather and climate events including extreme heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, and flooding. Last year the U.S. experienced a record-breaking 28 extreme weather and climate disasters whose costs each surpassed $1 billion. As a recent report from Moody’s shows, insurance costs have also been rising as disasters mount (see graph below). Many of these disasters bear the fingerprints of climate change. Continued development in high-risk areas is also increasing costs when disasters do strike. Insured losses are a big part of the costs measured but uninsured losses and incalculable losses—like loss of lives, and mental health impacts—are also mounting.

With the relentless rise in global average temperatures continuing, unfortunately, we can expect the trend of extreme weather and climate related disasters to continue. Today’s challenges in the insurance markets are likely just a taste of what’s to come.

Insurers of Last Resort

Florida has seen a number of private insurance companies go into receivership in the last few years, and Citizens Property Insurance, the state taxpayer-backed insurer of last resort, has taken on more policies as private insurers go out of business. The latest data show another uptick in Citizens policies in advance of what is expected to be an active hurricane season.

This trend of more and more policyholders moving from the private homeowners insurance market to state-backed insurance of “last resort”—called Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plans—is also happening in other highly exposed states like California, Louisiana, and North Carolina. In California, the FAIR plan’s exposure to loss is getting increasingly unsustainable, putting it at risk of insolvency. Data from CA FAIR Plan show that “as of March 2024 (partial fiscal year), the FAIR Plan’s total exposure is $340 billion, reflecting a 20% year-over-year increase.” (See chart below)

A report from Milliman shows that:

- Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corporation grew by +277% between 2017 and 2022, resulting in $423 billion of in-force Total Insured Value (TIV) at the end of 2022.

- The Louisiana Citizens Property Insurance Corporation experienced the highest overall growth over the period, +414% resulting in $41 billion of 2022 in-force TIV.

- The Washington FAIR Plan (WA FAIR Plan) showed a five-year exposure increase of +226%, with about $70 million in TIV at the end of 2022.

Turmoil in Public and Private Insurance Markets

In both the public and private insurance markets, climate-driven risks are creating turmoil. The private homeowner’s insurance market—which covers insurance against wildfires—has seen major insurers like State Farm and Allstate cease to offer new insurance policies in California, and rates for others going up (as Travelers Insurance announced recently). Similar actions are also happening in parts of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, which are also severely wildfire prone.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), administered by FEMA, is the primary source of flood insurance that isn’t covered by typical homeowners insurance. FEMA has also recently implemented changes to NFIP rates, with the intended aim of better reflecting current flood risk under the Risk Rating 2.0 program. Some of the steepest increases have come in states like Louisiana which are highly exposed to flooding; 10 states have sued FEMA to block the changes. And because Congress has long failed to enact affordability provisions—which the NAS, FEMA, and others have called for—these rate increases are causing significant hardship to many people with the least resources.

Much of the nation’s housing stock is also likely under-insured against flooding because only homes in FEMA’s high flood-risk zones with federally backed mortgages are required to carry flood insurance—and that insurance is likely inadequate given what the science shows about accelerating coastal flood risks, which are not captured by current FEMA flood maps.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has repeatedly called out the taxpayer-backed flood insurance program in its “High Risk Series” of reports on areas of exposure for the federal government. In its 2023 report, the GAO says: “The federal government needs to take additional actions to improve the long-term resilience of insured structures and crops. It also needs to address structural weaknesses in its insurance programs.”

The Role of Policymakers and Regulators

Last year, Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) launched an investigation into the climate-driven insurance crisis and sent letters to 41 insurance companies requesting more information on how they are addressing this problem. Earlier this month, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing on how climate change is challenging insurance markets. The hearing featured wrenching testimony from Deborah Wood, a Florida resident who has had to sell her home because of the unaffordability of insurance. Non-coastal states were also represented as Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) admitted in his opening statement that “Iowa had six property and casualty companies pull out of insuring Iowans.”

Private insurance—the category into which most homeowners’ insurance falls—is regulated at the state level by state insurance commissioners who are supposed to look out for the interests of consumers. However, their role can be different in different states, and even in the states with strong oversight, the power of regulators is somewhat limited. For example, California has tried to implement a moratorium on rate increases in the past, but that has only been possible on a temporary basis as wildfire impacts grow. Ultimately, some insurers are making the decision that it is unprofitable to operate in certain markets and are choosing to exit them.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners have jointly issued a call for data to better understand the impacts of climate-driven risks on the homeowners insurance market, with a focus on affordability and availability of insurance. The first tranche of data is expected this month; however, some of the most climate-exposed states—including Florida, Texas, and Louisiana—will likely choose not to participate.

Having access to the latest data and science to understand not just today’s risks, but how those risks will change over the lifetime of a property, is crucial. Congress and regulators need to ensure more transparency in the insurance market on how companies are evaluating risks as they make decisions about premiums. There also needs to be better information on what kinds of incentives companies are providing for adaptation measures that would help reduce risks. Transparency will also help regulators look out for the interests of consumers and ensure that companies are not using climate risks as a cover for dropping less profitable lines of business—for example in less wealthy communities.

The Limits of Insurance—and the Need for Just Resilience Policies

One sobering reality is that the pace and magnitude of the physical risks from climate change in all too many places is outpacing the ability of insurance to provide protection. Former California insurance commissioner Dave Jones has said, “I believe we’re marching toward an uninsurable future,” in many places. That will have significant consequences for the many people, homes, and the trillions of dollars of infrastructure assets in harm’s way, and we need to plan for it now.

Alongside the necessary but ultimately bounded role of insurance in a warming world, public and private decision makers must also shift investments away from business-as-usual maladaptive and risky choices to more resilient ones. The nation must scale up resources for climate resilience and ensure they are reaching communities in a just and equitable way. Funding for safe, affordable, and climate-resilient housing must be expanded. Some places just won’t be possible to insure indefinitely, but people need options for fair pathways away from the risks.

And we’ve got to sharply curtail heat-trapping emissions and phase out fossil fuels to limit catastrophic climate impacts and help keep people safe in an increasingly perilous world.

- The Insurance Industry Can Doom Us, or Help Save Us All ›

- As Insurers Cut Coverage Due to Climate Disasters, Senators Probe Continued Backing of Fossil Fuels ›

- Activists to Insurance Giants: 'End Your Support for Oil and Gas Now' ›

- US Insurance Giants Ditching Homeowners, But Still Underwriting Climate-Killing Coal Industry ›

- FEMA Limits Building in Flood Plains But 'Still Desperately Needs to Transform' | Common Dreams ›

- Helene's Catastrophic Potential Stokes Fear Amid Florida Insurance Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Insurance Companies Are Not Good Neighbors to Have in a Climate Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- As Planet Heads Toward 2.7°C Rise, Tracker Warns Global Climate Action Has 'Flatlined' | Common Dreams ›

- Congressional Report Warns of Climate Threat to US Insurance, Housing Markets | Common Dreams ›

- Amid LA Inferno, Home Insurers Under Fire for Policy Cancellations | Common Dreams ›

- Climate-Fueled Insurance Cost Hikes Putting American Dream 'Out of Reach' | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Like a Bad Neighbor, State Farm Is There... in California | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | What the Texas Floods Can Teach Us About Disaster Readiness in a Changing Climate | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | It’s Time to Be Honest About What Caused the Texas Floods: Fossil-Fueled Climate Change | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Roll up Your Sleeves for Climate Resilience Summer | Common Dreams ›

- As World Convenes in Brazil, WHO Warns of Dire Health Impacts of Climate Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Property Insurance Is the Canary in the Climate Coal Mine | Common Dreams ›

- Washington Homeowners Sue Big Oil Over Soaring Insurance Costs | Common Dreams ›