March 12 is Equal Pay Day, a reminder that there is still a significant pay gap between men and women in our country. The date represents how far into 2024 women would have to work on top of the hours they worked in 2023 simply to match what men were paid in 2023. Women were paid 21.8% less on average than men in 2023, after controlling for race and ethnicity, education, age, and geographic division.

There has been little progress in narrowing this gender wage gap over the past three decades, as shown in Figure A. While the pay gap declined between 1979 and 1994—due to men’s stagnant wages, not a tremendous increase in women’s wages—it has remained mostly flat since then.

The Gender Wage Gap Persists Across the Wage Distribution

The experience of men and women across the wage distribution differs considerably, but the gender wage gap persists no matter how it’s measured. Women are paid less than men as a result of occupational segregation, devaluation of women’s work, societal norms, and discrimination, all of which took root well before women entered the labor market. Figure B shows that women are paid less than men at all parts of the wage distribution.

What’s very stark from the data is that women with advanced degrees are paid less per hour, on average, than men with college degrees.

The wage gap is smallest among lower-wage workers, in part due to the minimum wage creating a wage floor. At the 10th percentile, women are paid $1.86 less an hour, or 12.8% less than men, while at the middle the wage gap is $3.87 an hour, or 14.9%. These low- and middle-wage gaps translate into annual earnings gaps of over $3,800 and $8,000, respectively, for a full-time worker. The 90th percentile is the highest wage category we can compare due to issues with topcoding in the data, which make it difficult to measure wages at the top of the distribution, particularly for men. Women are paid $14.74 less an hour, or 22.6% less, than men at the 90th percentile. That would translate into an annual earnings gap of over $30,000 for a full-time worker.

Women Are Paid Less Than Men at Every Education Level

Despite gains in educational attainment over the last five decades, women still face a significant wage gap. Among workers, women are more likely to graduate from college than men, and are more likely to receive a graduate degree than men. Even so, women are paid less than men at every education level, as shown in Figure C.

Among workers who have only a high school diploma, women are paid 21.3% less than men. Among workers who have a college degree, women are paid 26.8% less than men. That gap of $13.52 on an hourly basis translates to roughly $28,000 less annual earnings for a full-time worker. Women with an advanced degree also experience a significant the wage gap, at 25.2% in 2023. What’s very stark from the data is that women with advanced degrees are paid less per hour, on average, than men with college degrees. Men with a college degree only are paid $50.37 per hour on average compared with $48.21 for women with an advanced degree.

Black and Hispanic Women Experience the Largest Wage Gaps

If the overall gender pay gap isn’t enough cause for alarm, the wage gaps for Black and Hispanic women relative to white men are even larger due to compounded discrimination and occupational segregation based on both gender and race or ethnicity. In Figure D, we compare middle wages—or the average hourly wage between the 40th and 60th percentile of each group’s wage distribution—for white, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) women with that of white men.

White women and AAPI women are paid 83.1% and 90.3%, respectively, of what non-Hispanic white men are paid at the middle. Black women are paid only 69.8% of white men’s wages at the middle, a gap of $8.65 on an hourly basis which translates to roughly $18,000 less annual earnings for a full-time worker. For Hispanic women, the gap is even larger at the middle: Hispanic women are paid only 64.6% of white men’s wages, an hourly wage gap of $10.15. For a full-time worker, that gap is over $21,000 a year.

These pay gaps are even larger when examining average hourly wages for all workers instead of just the average for middle-wage workers because of the disproportionate share of highly paid workers who are white men, which pulls up their average. Using the average measure, Black and Hispanic women are paid 63.4% and 58.3%, respectively, of white men’s wages, an hourly wage gap of $14.80 for Black women and $16.90 for Hispanic women. Even when controlling for age, education, and geographic division, Black and Hispanic women are both paid about 68% of white men’s wages. In other words, very little of the observed difference in pay is explained by differences in education, experience, or regional economic conditions.

Policymakers Must Pursue a Range of Options to Close the Gender Pay Gap

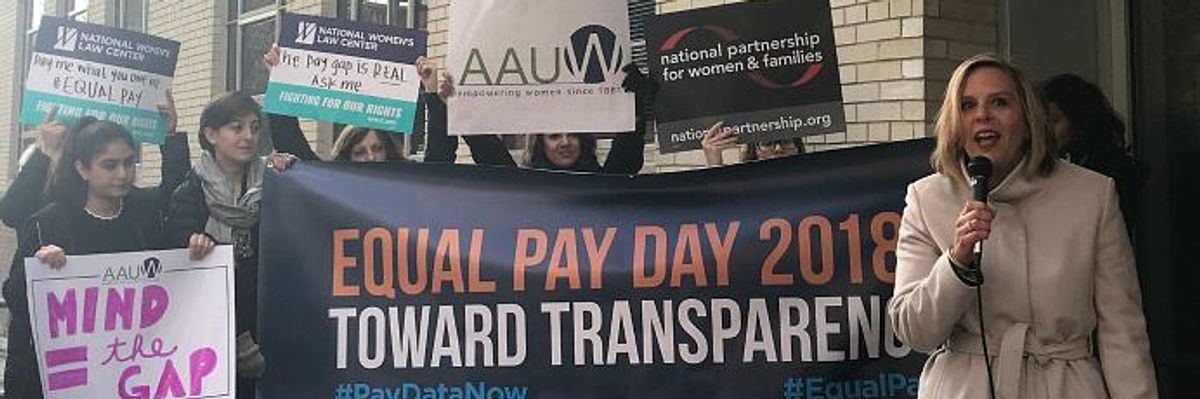

There is no silver bullet to solving pay equity, but rather a menu of policy options that can close not only the gender pay gap but also gaps by race and ethnicity. These include requiring federal reporting of pay by gender, race, and ethnicity; prohibiting employers from asking about pay history; requiring employers to post pay bands when hiring; and adequately staffing and funding the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission and other agencies charged with enforcement of nondiscrimination laws.

We also need policies that lift wages for most workers while also reducing gender and racial/ethnic pay gaps, such as running the economy at full employment, raising the federal minimum wage, and protecting and strengthening workers’ rights to bargain collectively for higher wages and benefits.