The first thing commuters saw when stepping into the Metro station beneath the Pentagon in late August was a poster for RTX: the world’s second largest defense contractor, formerly known as Raytheon.

RTX made $30.3 billion in sales to the U.S. government last year, 45% of its total income. To advertise to its biggest customer, why not target government decision-makers in the places they visit most? Thus, the thousands of commuters entering the Pentagon station each day were greeted by more than 60 RTX advertisements plastered across the walls, floors, escalators, and fare gates such that it was physically impossible to pass through the station without seeing one.

This ad campaign wasn’t the company’s first rodeo, either. Ten years ago, RTX placed advertisements in the Pentagon station to promote a satellite control system. That same project is now seven years late and billions of dollars over-cost.

The catch is that, technically, advertisers aren’t supposed to be able to do this, as the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA, which operates the greater D.C. metro system) forbids advertisements that “are intended to influence public policy.” But government contractors, reliant on public policy for their survival, are nonetheless allowed to promote their brands and hawk their products to the officials responsible for deciding whether or not to buy from them. A closer investigation into their marketing tactics reveals how companies like RTX and Google have taken advantage of this lax enforcement to hijack D.C.’s public transportation system for their own gain. WMATA is not just allowing it, they’re profiting from it.

Notes From Underground

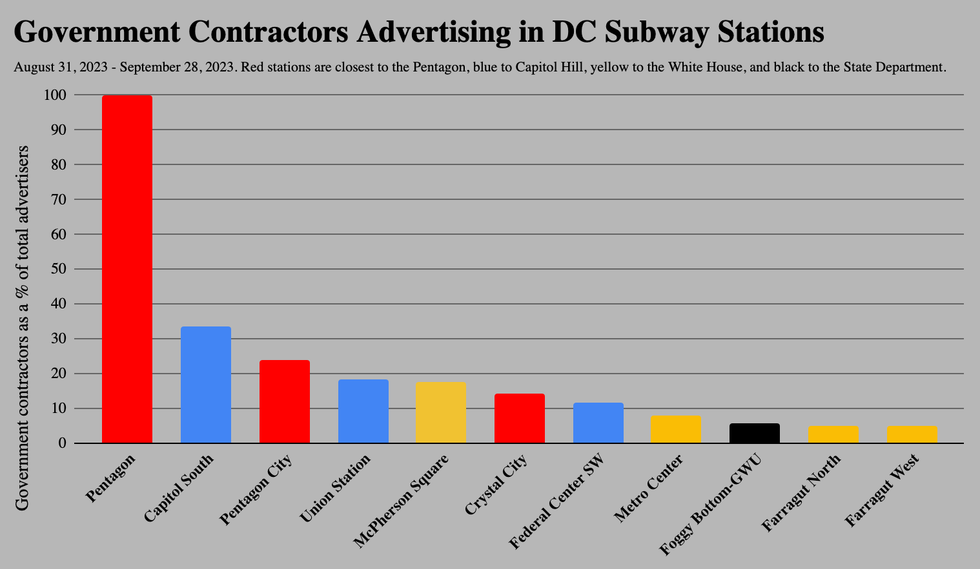

A graph shows the concentration of contractor advertisements at different D.C. Metro stations.

(Graphic: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

As the home to countless government agencies, Washington D.C.’s population is dense with people whose choices at work can affect the entire world. This has made the capital metro system a magnet for government contractors and other advertisers looking to shape policymakers’ activities.

Yet a systematic analysis of that advertising has proven difficult. WMATA does not make advertising data available to the public, and has yet to respond to multiple requests for the data. A similar request was denied by Outfront Media, the private marketing firm contracted by WMATA to handle transit ads.

So, I obtained what information I could the old-fashioned way—I rode the Metro, a lot. For five consecutive weeks, I visited 11 WMATA Metro stations and recorded the names of every advertiser. All were located within one mile of major policymaking institutions: Capitol Hill, the White House, the Pentagon, and the State Department.

Contractor advertising appears to be explicitly targeted at those with the greatest sway over government spending.

The survey recorded 75 different advertisers, excluding transit agencies. Fifteen received at least $5 million in financial awards from the federal government in fiscal year 2023. Four of those were universities and another was United Airlines, while the remaining 10 were government contractors. Altogether, these 10 contractors received approximately $83.1 billion from the federal government in FY2023.

Nine of the 10 advertising contractors count the Department of Defense (DOD) as their largest government customer: Boeing, CACI, General Dynamics, Google, IBM, KPMG, L3Harris, RTX, and SourceAmerica. Ads for McKesson, which does the vast majority of its government contracting for the Department of Veterans Affairs, were spotted only within the McPherson Square station—two blocks away from the VA headquarters.

While this survey was being conducted, Congress was preparing to meet in committee to negotiate the final version of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which annually authorizes hundreds of billions of dollars that ultimately go to Pentagon contractors.

The data suggests that contractors are most focused on targeting the Pentagon and Capitol Hill. Contractors made up just 6% of all advertisers in Foggy Bottom-GWU, the only stop near the State Department. In the four stops around the White House, they averaged 9%. Among the three stops closest to Capitol Hill, this number rises to 21%. In the three stations closest to the Pentagon, an average of 46% of all advertisers were contractors.

The Pentagon station, less than 200 feet from the building’s entrance, was 100% occupied by government contractors. In Capitol South, similarly close to the offices of the House of Representatives, one-third of advertisers were contractors. The focus on these two institutions illustrates their importance in keeping contract money flowing: a slim majority of the massive DOD budget goes to contractors each year, and the institution plays a major role in shaping its own budget. The House, meanwhile, is where all budget bills begin. In short, contractor advertising appears to be explicitly targeted at those with the greatest sway over government spending.

Speaking in Tongues

An RTX ad is displayed at the Pentagon City Metro station on September 7, 2023.

(Photo: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

This pattern goes well beyond correlation. Many contractor ads are designed to steer a small number of commuters—agency acquisition officers and congressional appropriations staffers—towards specific government policies. To accomplish this, contractors often use niche language that only their customers would understand. One ad spotted in four stations near Capitol Hill and the Pentagon displayed the tail of a jet above two screens of text: “ENABLES BEYOND BLOCK 4 / ALL THREE F-35 VARIANTS” and “THE SMART DECISION.”

This bizarre message, which caught the attention of social media earlier this year, is promoting RTX’s F135 engine. Estimated to cost $26 million each, these upgrades can be added to “all three” versions of the F-35 jet, whose astronomical cost overruns have helped turn it into the most expensive weapons program in human history. Years ago, Lockheed Martin advertised this same plane in stations near the Pentagon with its own twist on a classic neoconservative slogan: “Peace through strength. Lots of strength.” Today, RTX promises that its add-on goes “beyond” the Block 4 upgrade for these planes (which itself is running $5.9 billion over previous cost estimates).

RTX has bragged to investors about the expensive contracts for its F135 engines, but it still faces competition from other contractors. The conflict between the two is set to be addressed by Congress during conference negotiations for this year’s NDAA. To help secure its new revenue stream, RTX placed ads promoting it in places where the people working on the NDAA will most likely see them, using language that only they would understand. RTX did not reply to a request for comment.

In the past, some firms have been transparent about their narrow audiences. Controversial contractor Palantir, which has handled many confidential contracts, once advertised in the Pentagon station with materials reading: “THOSE WITH A NEED TO KNOW, KNOW.

Total Brand Experience

A Google ad is displayed at the Pentagon Metro station on September 28, 2023

(Photo: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

Outfront Media’s pitch to advertisers for the D.C. market area highlights its large audience of “political leaders, government employees, and corporate contractors.” To help reach them all, they offer a “Rail Station Domination” deal in 13 Metro stations to allow one advertiser to occupy much of the available space within, an opportunity, it says, to “transform commuters’ daily ride into a total ‘brand experience.’”

Outfront’s list of “Domination” stations includes brief descriptions of why they might be attractive to marketers: “U.S. Dept of Defense” for the Pentagon station, and “Capitol Hill” for Capitol South. Two other stations located near various regulatory agencies are listed simply as places to target “Government.” Contractors have long taken advantage of these deals, such as Lockheed Martin’s 2020 “domination” of Capitol South.

The Pentagon station, a prime target for reaching DOD staffers, was one of a kind. The Pentagon is the most expensive station to “dominate” according to Outfront Media data which I obtained, even though it has substantially fewer riders than some of the others. Advertising to the 665,786 commuters estimated to visit the Pentagon station in a four week period costs $198,000 (about 30 cents per commuter), before fees. Yet in Gallery Place-Chinatown, a station in downtown D.C. farther away from government buildings, it costs only $120,000 to reach more than three times as many people (5 cents per commuter).

The Pentagon is the most expensive station to “dominate” according to Outfront Media data which I obtained, even though it has substantially fewer riders than some of the others.

These pricing differences suggest that there is a unique value attached to commuters visiting the Pentagon. Another factor is the Pentagon’s unique layout, in which one advertiser can occupy the entire station for weeks on end, without any competition from others on digital screens. The five “domination” stations visited during this survey averaged 13.6 different advertisers over five weeks; the Pentagon featured only two. In the last week of August, every ad space inside the Pentagon station was occupied by RTX. For the entirety of September, it was Google.

Despite earning little from government contracts last year, Google ran a highly aggressive marketing campaign this September to attract more. Its domination of the Pentagon station featured over 60 ads about their commitment to partnering with the government on cybersecurity policy, one of which implied that the company was already acting in concert with the military: “The U.S. Department of Defense and Google are securing American digital defense systems.”

The company shied away from its nascent attempts to break into government contracting in 2018 after a controversial AI drone deal provoked employee protests. Google executives have more recently reversed course, increased their presence in northern Virginia, and unveiled “Google Public Sector” to fight for more defense contracts. Google Public Sector’s current managing director served as Chief Information Officer at the U.S. Navy until passing through the revolving door in March. The company’s success in winning part of a major software contract late last year suggests its efforts are already paying off.

At the same time that Google was dominating the Pentagon station, a second ad campaign downtown promoted the “Google Public Sector Forum,” where company executives spoke alongside current Pentagon officials. Reached for comment, the Defense Department emphasized that guidelines were in place to ensure that "DOD personnel participating in public engagements” acted in ways “appropriate and consistent with DOD and U.S. government policies.”

Google’s apparent dual advertising strategy reflects its diverse goals in reaching policymakers: accessing the deep pool of DOD contracting funds, lobbying Congress on a wide variety of legislation, and burnishing its image in the face of a historic anti-trust lawsuit filed against it by the Justice Department earlier this year.

Google and Outfront Media did not reply to a request for comment.

Defining “Influence”

The Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton was developed under the Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) program.

(Photo: U.S. Navy)

Sitting awkwardly with this phenomenon is a strange fact: According to WMATA policy, “Advertisements that are intended to influence public policy are prohibited.” Ads for specific military equipment are clearly meant to “influence” government acquisitions, which are “public policy” by definition. Nonetheless, Pentagon contractors appear to flaunt this rule with impunity.

While WMATA has declined a number of political ads before, it is still quite common for advertisers to push the limits of what qualifies as “intended to influence public policy.” No one pushes this boundary further than contractors. Prior to the ban’s creation in 2015, contractors openly acknowledged that they hoped to influence public policy. When Northrop Grumman advertised its Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) system in the Pentagon station in 2007, a company spokesman said: “There is an ongoing campaign to win the BAMS contract… The Washington, D.C., area is where our customer base is, and we do want to build awareness for our products and services.”

WMATA declined to comment on questions related to the rule due to “pending litigation on this issue.” The American Civil Liberties Union has sued over this and other WMATA policies as violations of advertisers’ free speech rights, and the case was recently approved to move forward.

The seemingly arbitrary enforcement of WMATA’s ban on ads influencing public policy allows contractors to recycle government funds back into efforts to acquire more government funds.

Further complicating matters is a federal law banning contractors from spending public funds on “influencing or attempting to influence” government officials towards providing them with additional contracts. The rule does not seem to have dissuaded contractors, even those who derive the majority of their revenues from the federal government, from targeted advertising campaigns. (DOD spokesman Jeff Jurgensen emphasized that the agency complies with all relevant acquisitions regulations.)

Advertisers subsidize the D.C. Metro system by providing revenue that would otherwise need to come from either commuters or the government. WMATA hired Outfront Media to “maximize the revenue potential” of public transit assets, incentivizing the company to always go with the highest bidder. Still, WMATA’s budget for next year projects that Metro ads will only bring in $10.3 million, roughly 0.75% of the system’s total funding. This might save money on the front end, but advertisements encouraging billions in inefficient government spending could easily wind up costing taxpayers more over time, such that direct subsidies to replace WMATA’s revenues from contractor ads could ultimately save money.

The seemingly arbitrary enforcement of WMATA’s ban on ads influencing public policy allows contractors to recycle government funds back into efforts to acquire more government funds. This cycle encourages public officials to make choices based on power and reach, rather than cost-efficiency, fairness, or a rational defense strategy. As long as companies making money from policymakers’ decisions are allowed to advertise in the D.C. transit system, this corrupt process will continue to thrive.