SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

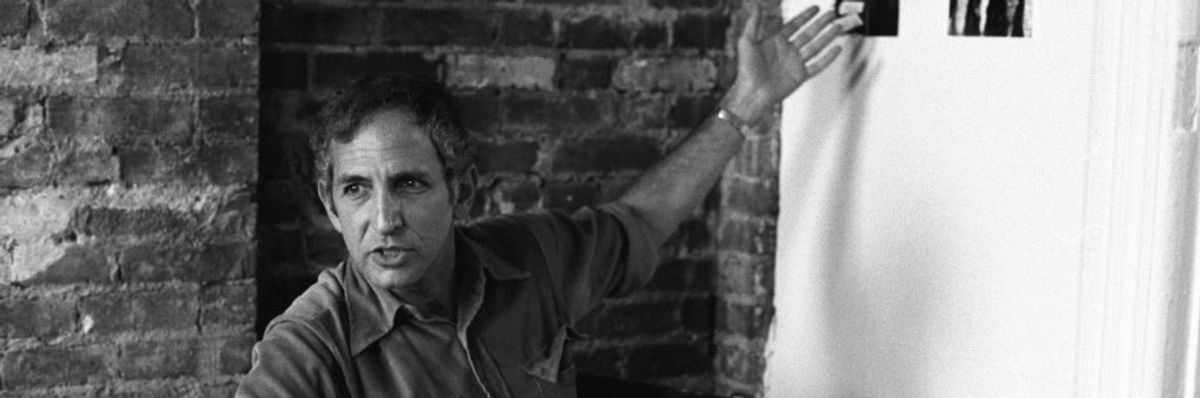

American military analyst and political activist Daniel Ellsberg gestures towards a picture on a wall, October 10, 1976.

It isn’t just the Pentagon Papers that matter, but also Elsberg’s transformation, his awareness that the harm the war was doing, the innocent people it was killing, the unending hell it was creating, mattered.

There’s a crucial, overlooked aspect of Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy that’s very much worth saluting, you might say: his transformation from a believer in the Vietnam war to a horrified opponent of it, ready to risk prison time to bring classified truth about its pointlessness into public awareness.

Ellsberg, who died on June 16 at age 92, had been part of the military-industrial establishment in the 1960s—a smart young man working as a Pentagon consultant at the Rand Corporation think tank. In the mid-’60s. he wound up spending two years in Vietnam, on a mission for the State Department to study counterinsurgency. He traveled through most of the country—witnessing not simply the war up close but Vietnam itself, and the people who lived there.

A few things became obvious. Despite then-President Richard Nixon’s commitment to “winning” the war—and continuing America’s tradition of greatness—“there was no prospect of progress of any kind,” Ellsberg told The Guardian, “so the war should not be continued.”

“ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend.”

Beyond that realization was something even more significant: “ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend. In fact, most of them had never met a Vietnamese.”

The war was no longer an abstraction to Ellsberg. It was hell visited upon humanity. It cut him to his soul. Now what? He continued his work. As of 1969, he had 7,000 pages of documents in his safe—a study of the tumult in Vietnam from 1945, when it was still a French colony, to 1967—which indicated that president after president after president knew the war was absurd and unwinnable, but kept on “pursuing U.S. interests” there, at extraordinary cost to the Vietnamese people, who didn’t matter at all.

Finally he decided to act. He had met young people willing to go to prison in defiance of the draft. He knew he couldn’t simply shrug his shoulders and continue on with his career. He spent eight months secretly copying his document trove, eventually releasing the papers to The New York Times and, ultimately, 19 papers in all, which defied Nixon’s orders that the contents were a national security risk and must not be published.

The war continued anyway, but public outrage, both within and outside the military, gradually prevailed and the U.S. pulled out, abandoning the carnage it had created and putting the consequences out of its mind. After all, the military-industrial establishment had its own wound—a.k.a., “Vietnam syndrome,” public disgust at stupid and brutal wars—it needed to overcome, which of course it eventually did.

All of which leads me back to Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy. I think it wasn’t simply the Pentagon Papers themselves—and the lies and high-level bullshit they revealed—but also Ellsberg’s transformation: his awareness that the harm the war was doing, the innocent people it was killing, the unending hell it was creating, mattered. “Vietnam became very real to me.”

In other words, war is not an abstraction—a strategic game played by experts, with winning being the entirely of what matters. This truth sits in the collective human soul. It continues to resonate.

Indeed, the legacy of the Vietnam War—and the war itself—has not ended. War means the right to murder... an entire country. Consider, for instance, the U.S. war crime initially labeled Operation Hades, which eventually morphed into the happy-sounding Operation Ranch Hand.

As the War Legacies Project reports: “Between 1961 and 1971, the U.S. sprayed 12 million gallons of dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange and 8 million gallons of other herbicides on Vietnam and large areas of both avowedly neutral Laos and Cambodia.”

The U.S. Air Force flew 20,000 herbicide missions over the country with the intention of defoliating hardwood tropical forests, plantations, mangroves, brush lands, and other areas of woody vegetation: “about 25 million acres of dense tropical forests in South Vietnam, an area approximately the size of the state of Kentucky. The program’s official objective was to deploy tactical code-named ‘Rainbow herbicides’ that could denude this tropical-agricultural landscape, which provided cover and subsistence for counterinsurgency forces.”

War strategy prevails! Would such ecocide—a word birthed by U.S. actions in Vietnam—have been justified even if the war were “winnable”? Obviously not. Denuded tropical forests, terrifying birth defects. Welcome to the realities that war wagers choose not to notice.

And then, of course, there are the unexploded shells and land mines strewn across the country’s landscape, blowing people’s arms off, killing children. As Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh pointed out earlier this year, these munitions have killed more than 40,000 people and injured 60,000 since 1975. Can we let this reality sink in?

This is the ongoing legacy of dehumanization, without which war would be impossible to wage. As one vet described what his training taught him: “The enemy is not a human being. He has no mother or father, no sister or brother.”

No, he’s just in the way. The whole planet’s in the way.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

There’s a crucial, overlooked aspect of Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy that’s very much worth saluting, you might say: his transformation from a believer in the Vietnam war to a horrified opponent of it, ready to risk prison time to bring classified truth about its pointlessness into public awareness.

Ellsberg, who died on June 16 at age 92, had been part of the military-industrial establishment in the 1960s—a smart young man working as a Pentagon consultant at the Rand Corporation think tank. In the mid-’60s. he wound up spending two years in Vietnam, on a mission for the State Department to study counterinsurgency. He traveled through most of the country—witnessing not simply the war up close but Vietnam itself, and the people who lived there.

A few things became obvious. Despite then-President Richard Nixon’s commitment to “winning” the war—and continuing America’s tradition of greatness—“there was no prospect of progress of any kind,” Ellsberg told The Guardian, “so the war should not be continued.”

“ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend.”

Beyond that realization was something even more significant: “ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend. In fact, most of them had never met a Vietnamese.”

The war was no longer an abstraction to Ellsberg. It was hell visited upon humanity. It cut him to his soul. Now what? He continued his work. As of 1969, he had 7,000 pages of documents in his safe—a study of the tumult in Vietnam from 1945, when it was still a French colony, to 1967—which indicated that president after president after president knew the war was absurd and unwinnable, but kept on “pursuing U.S. interests” there, at extraordinary cost to the Vietnamese people, who didn’t matter at all.

Finally he decided to act. He had met young people willing to go to prison in defiance of the draft. He knew he couldn’t simply shrug his shoulders and continue on with his career. He spent eight months secretly copying his document trove, eventually releasing the papers to The New York Times and, ultimately, 19 papers in all, which defied Nixon’s orders that the contents were a national security risk and must not be published.

The war continued anyway, but public outrage, both within and outside the military, gradually prevailed and the U.S. pulled out, abandoning the carnage it had created and putting the consequences out of its mind. After all, the military-industrial establishment had its own wound—a.k.a., “Vietnam syndrome,” public disgust at stupid and brutal wars—it needed to overcome, which of course it eventually did.

All of which leads me back to Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy. I think it wasn’t simply the Pentagon Papers themselves—and the lies and high-level bullshit they revealed—but also Ellsberg’s transformation: his awareness that the harm the war was doing, the innocent people it was killing, the unending hell it was creating, mattered. “Vietnam became very real to me.”

In other words, war is not an abstraction—a strategic game played by experts, with winning being the entirely of what matters. This truth sits in the collective human soul. It continues to resonate.

Indeed, the legacy of the Vietnam War—and the war itself—has not ended. War means the right to murder... an entire country. Consider, for instance, the U.S. war crime initially labeled Operation Hades, which eventually morphed into the happy-sounding Operation Ranch Hand.

As the War Legacies Project reports: “Between 1961 and 1971, the U.S. sprayed 12 million gallons of dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange and 8 million gallons of other herbicides on Vietnam and large areas of both avowedly neutral Laos and Cambodia.”

The U.S. Air Force flew 20,000 herbicide missions over the country with the intention of defoliating hardwood tropical forests, plantations, mangroves, brush lands, and other areas of woody vegetation: “about 25 million acres of dense tropical forests in South Vietnam, an area approximately the size of the state of Kentucky. The program’s official objective was to deploy tactical code-named ‘Rainbow herbicides’ that could denude this tropical-agricultural landscape, which provided cover and subsistence for counterinsurgency forces.”

War strategy prevails! Would such ecocide—a word birthed by U.S. actions in Vietnam—have been justified even if the war were “winnable”? Obviously not. Denuded tropical forests, terrifying birth defects. Welcome to the realities that war wagers choose not to notice.

And then, of course, there are the unexploded shells and land mines strewn across the country’s landscape, blowing people’s arms off, killing children. As Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh pointed out earlier this year, these munitions have killed more than 40,000 people and injured 60,000 since 1975. Can we let this reality sink in?

This is the ongoing legacy of dehumanization, without which war would be impossible to wage. As one vet described what his training taught him: “The enemy is not a human being. He has no mother or father, no sister or brother.”

No, he’s just in the way. The whole planet’s in the way.

There’s a crucial, overlooked aspect of Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy that’s very much worth saluting, you might say: his transformation from a believer in the Vietnam war to a horrified opponent of it, ready to risk prison time to bring classified truth about its pointlessness into public awareness.

Ellsberg, who died on June 16 at age 92, had been part of the military-industrial establishment in the 1960s—a smart young man working as a Pentagon consultant at the Rand Corporation think tank. In the mid-’60s. he wound up spending two years in Vietnam, on a mission for the State Department to study counterinsurgency. He traveled through most of the country—witnessing not simply the war up close but Vietnam itself, and the people who lived there.

A few things became obvious. Despite then-President Richard Nixon’s commitment to “winning” the war—and continuing America’s tradition of greatness—“there was no prospect of progress of any kind,” Ellsberg told The Guardian, “so the war should not be continued.”

“ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend.”

Beyond that realization was something even more significant: “ ...Vietnam became very real to me and the people dying became real and I had Vietnamese friends. It occurs to me I don’t know of anyone of my level or higher—any deputy assistant secretary, any assistant secretary, any cabinet secretary—who had a Vietnamese friend. In fact, most of them had never met a Vietnamese.”

The war was no longer an abstraction to Ellsberg. It was hell visited upon humanity. It cut him to his soul. Now what? He continued his work. As of 1969, he had 7,000 pages of documents in his safe—a study of the tumult in Vietnam from 1945, when it was still a French colony, to 1967—which indicated that president after president after president knew the war was absurd and unwinnable, but kept on “pursuing U.S. interests” there, at extraordinary cost to the Vietnamese people, who didn’t matter at all.

Finally he decided to act. He had met young people willing to go to prison in defiance of the draft. He knew he couldn’t simply shrug his shoulders and continue on with his career. He spent eight months secretly copying his document trove, eventually releasing the papers to The New York Times and, ultimately, 19 papers in all, which defied Nixon’s orders that the contents were a national security risk and must not be published.

The war continued anyway, but public outrage, both within and outside the military, gradually prevailed and the U.S. pulled out, abandoning the carnage it had created and putting the consequences out of its mind. After all, the military-industrial establishment had its own wound—a.k.a., “Vietnam syndrome,” public disgust at stupid and brutal wars—it needed to overcome, which of course it eventually did.

All of which leads me back to Daniel Ellsberg’s legacy. I think it wasn’t simply the Pentagon Papers themselves—and the lies and high-level bullshit they revealed—but also Ellsberg’s transformation: his awareness that the harm the war was doing, the innocent people it was killing, the unending hell it was creating, mattered. “Vietnam became very real to me.”

In other words, war is not an abstraction—a strategic game played by experts, with winning being the entirely of what matters. This truth sits in the collective human soul. It continues to resonate.

Indeed, the legacy of the Vietnam War—and the war itself—has not ended. War means the right to murder... an entire country. Consider, for instance, the U.S. war crime initially labeled Operation Hades, which eventually morphed into the happy-sounding Operation Ranch Hand.

As the War Legacies Project reports: “Between 1961 and 1971, the U.S. sprayed 12 million gallons of dioxin-contaminated Agent Orange and 8 million gallons of other herbicides on Vietnam and large areas of both avowedly neutral Laos and Cambodia.”

The U.S. Air Force flew 20,000 herbicide missions over the country with the intention of defoliating hardwood tropical forests, plantations, mangroves, brush lands, and other areas of woody vegetation: “about 25 million acres of dense tropical forests in South Vietnam, an area approximately the size of the state of Kentucky. The program’s official objective was to deploy tactical code-named ‘Rainbow herbicides’ that could denude this tropical-agricultural landscape, which provided cover and subsistence for counterinsurgency forces.”

War strategy prevails! Would such ecocide—a word birthed by U.S. actions in Vietnam—have been justified even if the war were “winnable”? Obviously not. Denuded tropical forests, terrifying birth defects. Welcome to the realities that war wagers choose not to notice.

And then, of course, there are the unexploded shells and land mines strewn across the country’s landscape, blowing people’s arms off, killing children. As Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh pointed out earlier this year, these munitions have killed more than 40,000 people and injured 60,000 since 1975. Can we let this reality sink in?

This is the ongoing legacy of dehumanization, without which war would be impossible to wage. As one vet described what his training taught him: “The enemy is not a human being. He has no mother or father, no sister or brother.”

No, he’s just in the way. The whole planet’s in the way.