In Richard Connell’s popular short story “The Most Dangerous Game,” hunter Sanger Rainsford goes overboard while sailing to the Amazon, washing up on an island owned by deceivingly charismatic General Zaroff. Rainsford expects Zaroff to help him off the island, but instead, Zaroff invites him to participate in a hunt.

A hunt, to Rainsford’s utter disbelief, in which he is the prey.

Our reckless pursuit of economic growth has become society’s “most dangerous game.” It keeps us trapped on an island of inequality, environmental degradation, and corporate power, all while convincing us there’s still a chance we can win if we continue to play.

To win this game, we can’t keep playing by the rules, but rewrite them entirely. We can start by challenging one of the most dominant rules of the growth model: Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

But there is no “winning” in a game dependent on the exploitation of people and nature. As long as “growth” is defined by profits and production, people and the planet will always lose.

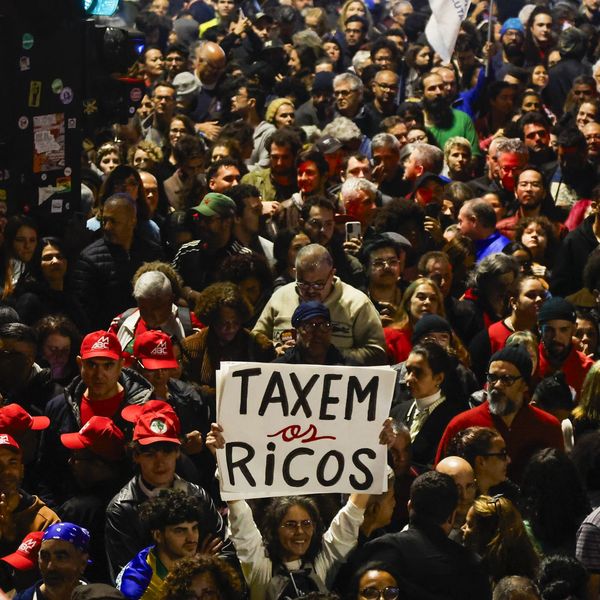

That is, unless you are one of the few Zaroffs of the world: According to an Oxfam report, the world’s top 1% own more wealth than 95% of humanity, and over the past 30 years, income inequality has steadily risen to the point where many economists believe wealth is more stratified today than any time since the Gilded Age.

If economic growth doesn’t deliver its promised benefits, then why do we continue to play? Because those who preach economic growth as a path to prosperity—usually the same people who bag the most benefit—have engineered a game of forced “choice:” Hunt, or be hunted. As Zaroff explains to Rainsford, “I give him his option, of course.” But if they decline, he hands them over to his servant for torture. “Invariably,” Zaroff muses, “they choose the hunt.”

The same logic is used to silo economic and environmental objectives, perpetuating the false premise that reducing poverty and raising living standards must come at the cost of climate action. Such “choice” is equally manufactured—if economic growth is truly a means of improving societal well-being, shouldn’t actions that secure and sustain access to basic necessities be a vital part of our economy?

Even Americans seem to agree that economic growth is an incomplete measure of prosperity. In a nationally-representative survey of 3,000 participants, conducted by survey organization Verasight between October 21 and November 5, only 12.8% (with a 2.3% margin of error) responded that economic growth is a “mostly accurate” way of assessing societal well-being. The rest were skeptical, with 50.8% calling it “somewhat accurate” and 36.5% deeming it inaccurate altogether.

And yet, despite the dissatisfaction, dissonance, and destruction that our economic model begets, pundits and policymakers “invariably” brandish growth as the hallmark of prosperity. Meanwhile, the Zaroffs of the world continue to indulge their unchecked appetite for profit, capitalizing off the preservation of the status quo.

To win this game, we can’t keep playing by the rules, but rewrite them entirely. We can start by challenging one of the most dominant rules of the growth model: Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

GDP is a measure of aggregate production, not a reflection of progress and well-being. It excludes the costs of pollution and exploitation and ignores 16.4 billion hours of unpaid labor, much of which is performed by women. It also omits many non-materialistic goods (health, family, and equality) that define happiness and quality of life. In fact, economists have always warned against conflating GDP with societal well-being—even one of its founders, Simon Kuznets, told Congress that GDP was a poor tool for policymaking.

As Robert Kennedy put it in his 1968 election speech, GDP “measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.” By adopting more inclusive measures of progress that consider health, equality, and environmental well-being, we can move beyond the flawed metric of GDP as a measure of prosperity. In doing so, we build economies that prioritize people and the planet instead of outrageous profits.

Such measures are already gaining traction in the U.S. and across the globe. For example, India’s Ease of Living Index assesses the well-being of 114 Indian cities, using a total of 50 indicators that fall under three pillars: Quality of Life, economic ability, and sustainability. At the international scale, the United Nations is working to advance a “Human Rights Economy” that anchors all economic decisions in human rights. In the U.S., Vermont became the first state to adopt an alternative to GDP called the “Genuine Progress Indicator” in 2012, shortly followed by Maryland and 19 other states.

These measures aren’t perfect, nor should they be the only way we address a system that continues to inflict irreparable damage on global ecosystems and communities. However, they play a crucial role in disrupting our current growth paradigm, establishing an economic model where well-being isn’t exclusive to the wealthy, and where societal and environmental objectives are aligned.

It’s time we expose the injustices of our economic system, rewrite the rules, and beat the Zaroffs of the world at their own game.