SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

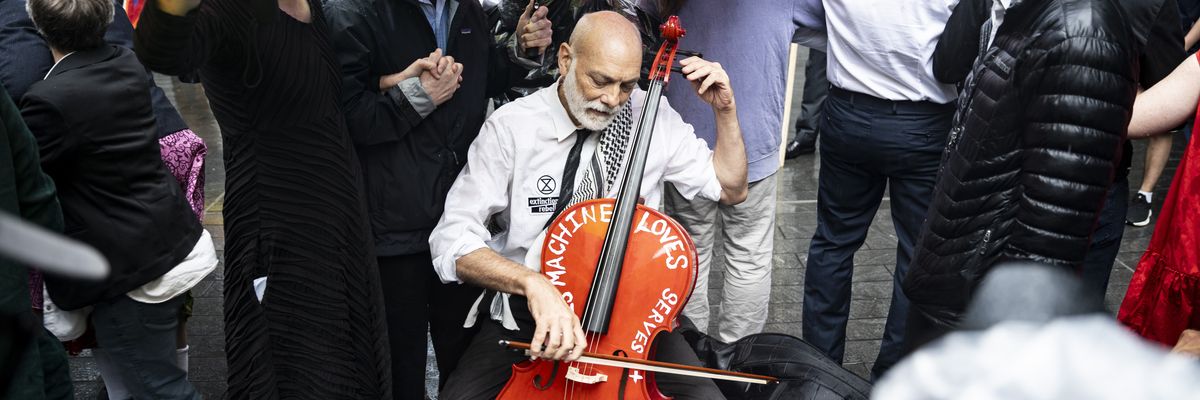

John Mark Rozendaal plays cello in defiance of a restraining order outside CitiBank’s headquarters in New York City on August 8, 2024.

Biologist Sandra Steingraber was invited to speak as climate activist John Mark Rozendaal disobeyed a restraining order to play cello outside CitiBank’s headquarters. However, that speech was never delivered.

On August 8, 63-year-old professional cellist, climate activist, and grandfather, John Mark Rozendaal, was arrested while playing the opening strains of Bach’s “Suites for Cello” outside of CitiBank’s world headquarters in Manhattan. Rozendaal is one of the leaders of the ongoing Summer of Heat civil disobedience campaign that has targeted CitiBank for financing new fossil fuel projects. Earlier this month, Citibank used false allegations to obtain a restraining order to prevent Rozendaal, along with author and campaign leader Alec Connon, from returning to Citibank headquarters or risk being charged with criminal contempt, a crime which carries a maximum seven-year jail sentence. Biologist Sandra Steingraber was invited to bear witness to his restraining order-defying performance and speak at a press event about the significance of his actions. However, that speech was never delivered. Just as Rozendaal began to play the first measures of the suite, police rushed in. Rozendaal and Connon were arrested, as were Steingraber and 13 others in attendance who had formed a circle around the musician as he played. This is the speech that was not delivered.

Good morning. My name is Sandra Steingraber. I’m a PhD biologist, and I like nothing more than to talk about data.

But today, we are here to witness an extraordinary act of courage, and I’m going to speak very personally.

I grew up in coal-country Illinois and was adopted out of a Methodist orphanage. I was a sensitive, introverted child who struggled with human attachment and a sense of belonging. By the time I was 14, I had fallen in love with two things: the Polish composer Frederic Chopin and photosynthesis.

Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

The idea that I could, with my own fingers, turn black notes on a page—assembled more than a century earlier—into something divinely beautiful was thrilling to me. When I played Chopin, I felt a connection to all the other pianists who had, for generations before me, memorized and practiced this same score for their own recitals.

Meanwhile, the opera of photosynthesis, which takes place inside the miniature Quonset huts called chloroplasts, connected me to the origins of life itself. The idea that green plants can draw in all our exhaled breath through the stomata of their leaves and, in the presence of sunlight, spin carbon dioxide together with water was awesome to me.

With the aid of cytochrome transport systems and leaping electrons, plants undertake an exquisitely beautiful act of biochemical self-creation. They make themselves. They exhale oxygen. And they feed us all.

The biological phenomenon of photosynthesis gave me a sense of ancestry.

By the time I went to college, I had discovered two things: 1) My ear for music was much better than my execution, which was not great; 2) I really loved trees.

So, I forsook the piano for plant ecology and, for my PhD research I learned the skills of dendrochronology, which allowed me to reconstruct the centuries-long history of a forest by studying the patterns of tree rings inside the heartwood of 200-year-old red pines.

The inside of a tree is a living scroll that tells the story—if you are trained to read the language of xylem and phloem—of the entire ecosystem. You can learn, for example, which years great forest fires swept through or which years had especially long winters. I became a historian of forests by studying the rings of the deep inside the trunks of individual trees.

I would have liked nothing better than to spend my life studying trees. But the acceleration of the climate crisis is now torching forests around the world. And drowning them with saltwater. And ravaging them with emergent diseases. And driving their pollinators into extinction. And otherwise stressing them to the point where they can no longer remove and sequester carbon dioxide from the air around them.

So, that’s why I became a civil disobedient with the Summer of Heat campaign. My responsibility as a plant biologist in this moment in human history is to do more than just teach photosynthesis and praise trees. All the oxygen we breathe is provided to us by plants, and they are in trouble. And governments aren’t acting. And banks like Citi keep on financing new fossil fuel projects that are ravaging ecosystems.

For me, the extraordinary concert we are about to witness is the place where botany and music come together.

Orchestral instruments like cellos and violins—as well as the bows drawn across their strings—are made from trees. And not just any trees but tree species that have what musicians call tonewood.

Pernambuco. Ebony. Certain species of maple and spruce.

These trees have cell walls with acoustical properties that vibrate in certain frequencies and, if they are all uniform in size and density, provide the richness of sound that we experience as musical. Different woods have different resonant qualities due to the ratio of cellulose and lignan. Typically, trees used to make classicial musical instruments are 200-400 years old with 20-inch trunks and tree rings that show slow and steady growth.

In a warming climate, however, annual growth rings have become less consistent in size, and the wood has become softer. Instrument-making trees are also increasingly targeted by emerging insect pests.

Trees with tonewood are now growing in more extreme weather conditions and enduring more frequent droughts. Those conditions alter their cellular architecture in ways that alter the tonal qualities of the wooden soundboards of the musical instruments made from their wood. As a result, orchestral music will sound different in the future. Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

Fifty years ago, playing a Chopin nocturne had the power to stop me from self-injuring. Listening to my friend John Mark Rozendaal defy Citi’s attempt to silence peaceful protest again the financing of climate ruin by performing Bach’s “Suites for Cello” will, I believe, have the power to call us all to stop injury to the planet.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On August 8, 63-year-old professional cellist, climate activist, and grandfather, John Mark Rozendaal, was arrested while playing the opening strains of Bach’s “Suites for Cello” outside of CitiBank’s world headquarters in Manhattan. Rozendaal is one of the leaders of the ongoing Summer of Heat civil disobedience campaign that has targeted CitiBank for financing new fossil fuel projects. Earlier this month, Citibank used false allegations to obtain a restraining order to prevent Rozendaal, along with author and campaign leader Alec Connon, from returning to Citibank headquarters or risk being charged with criminal contempt, a crime which carries a maximum seven-year jail sentence. Biologist Sandra Steingraber was invited to bear witness to his restraining order-defying performance and speak at a press event about the significance of his actions. However, that speech was never delivered. Just as Rozendaal began to play the first measures of the suite, police rushed in. Rozendaal and Connon were arrested, as were Steingraber and 13 others in attendance who had formed a circle around the musician as he played. This is the speech that was not delivered.

Good morning. My name is Sandra Steingraber. I’m a PhD biologist, and I like nothing more than to talk about data.

But today, we are here to witness an extraordinary act of courage, and I’m going to speak very personally.

I grew up in coal-country Illinois and was adopted out of a Methodist orphanage. I was a sensitive, introverted child who struggled with human attachment and a sense of belonging. By the time I was 14, I had fallen in love with two things: the Polish composer Frederic Chopin and photosynthesis.

Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

The idea that I could, with my own fingers, turn black notes on a page—assembled more than a century earlier—into something divinely beautiful was thrilling to me. When I played Chopin, I felt a connection to all the other pianists who had, for generations before me, memorized and practiced this same score for their own recitals.

Meanwhile, the opera of photosynthesis, which takes place inside the miniature Quonset huts called chloroplasts, connected me to the origins of life itself. The idea that green plants can draw in all our exhaled breath through the stomata of their leaves and, in the presence of sunlight, spin carbon dioxide together with water was awesome to me.

With the aid of cytochrome transport systems and leaping electrons, plants undertake an exquisitely beautiful act of biochemical self-creation. They make themselves. They exhale oxygen. And they feed us all.

The biological phenomenon of photosynthesis gave me a sense of ancestry.

By the time I went to college, I had discovered two things: 1) My ear for music was much better than my execution, which was not great; 2) I really loved trees.

So, I forsook the piano for plant ecology and, for my PhD research I learned the skills of dendrochronology, which allowed me to reconstruct the centuries-long history of a forest by studying the patterns of tree rings inside the heartwood of 200-year-old red pines.

The inside of a tree is a living scroll that tells the story—if you are trained to read the language of xylem and phloem—of the entire ecosystem. You can learn, for example, which years great forest fires swept through or which years had especially long winters. I became a historian of forests by studying the rings of the deep inside the trunks of individual trees.

I would have liked nothing better than to spend my life studying trees. But the acceleration of the climate crisis is now torching forests around the world. And drowning them with saltwater. And ravaging them with emergent diseases. And driving their pollinators into extinction. And otherwise stressing them to the point where they can no longer remove and sequester carbon dioxide from the air around them.

So, that’s why I became a civil disobedient with the Summer of Heat campaign. My responsibility as a plant biologist in this moment in human history is to do more than just teach photosynthesis and praise trees. All the oxygen we breathe is provided to us by plants, and they are in trouble. And governments aren’t acting. And banks like Citi keep on financing new fossil fuel projects that are ravaging ecosystems.

For me, the extraordinary concert we are about to witness is the place where botany and music come together.

Orchestral instruments like cellos and violins—as well as the bows drawn across their strings—are made from trees. And not just any trees but tree species that have what musicians call tonewood.

Pernambuco. Ebony. Certain species of maple and spruce.

These trees have cell walls with acoustical properties that vibrate in certain frequencies and, if they are all uniform in size and density, provide the richness of sound that we experience as musical. Different woods have different resonant qualities due to the ratio of cellulose and lignan. Typically, trees used to make classicial musical instruments are 200-400 years old with 20-inch trunks and tree rings that show slow and steady growth.

In a warming climate, however, annual growth rings have become less consistent in size, and the wood has become softer. Instrument-making trees are also increasingly targeted by emerging insect pests.

Trees with tonewood are now growing in more extreme weather conditions and enduring more frequent droughts. Those conditions alter their cellular architecture in ways that alter the tonal qualities of the wooden soundboards of the musical instruments made from their wood. As a result, orchestral music will sound different in the future. Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

Fifty years ago, playing a Chopin nocturne had the power to stop me from self-injuring. Listening to my friend John Mark Rozendaal defy Citi’s attempt to silence peaceful protest again the financing of climate ruin by performing Bach’s “Suites for Cello” will, I believe, have the power to call us all to stop injury to the planet.

On August 8, 63-year-old professional cellist, climate activist, and grandfather, John Mark Rozendaal, was arrested while playing the opening strains of Bach’s “Suites for Cello” outside of CitiBank’s world headquarters in Manhattan. Rozendaal is one of the leaders of the ongoing Summer of Heat civil disobedience campaign that has targeted CitiBank for financing new fossil fuel projects. Earlier this month, Citibank used false allegations to obtain a restraining order to prevent Rozendaal, along with author and campaign leader Alec Connon, from returning to Citibank headquarters or risk being charged with criminal contempt, a crime which carries a maximum seven-year jail sentence. Biologist Sandra Steingraber was invited to bear witness to his restraining order-defying performance and speak at a press event about the significance of his actions. However, that speech was never delivered. Just as Rozendaal began to play the first measures of the suite, police rushed in. Rozendaal and Connon were arrested, as were Steingraber and 13 others in attendance who had formed a circle around the musician as he played. This is the speech that was not delivered.

Good morning. My name is Sandra Steingraber. I’m a PhD biologist, and I like nothing more than to talk about data.

But today, we are here to witness an extraordinary act of courage, and I’m going to speak very personally.

I grew up in coal-country Illinois and was adopted out of a Methodist orphanage. I was a sensitive, introverted child who struggled with human attachment and a sense of belonging. By the time I was 14, I had fallen in love with two things: the Polish composer Frederic Chopin and photosynthesis.

Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

The idea that I could, with my own fingers, turn black notes on a page—assembled more than a century earlier—into something divinely beautiful was thrilling to me. When I played Chopin, I felt a connection to all the other pianists who had, for generations before me, memorized and practiced this same score for their own recitals.

Meanwhile, the opera of photosynthesis, which takes place inside the miniature Quonset huts called chloroplasts, connected me to the origins of life itself. The idea that green plants can draw in all our exhaled breath through the stomata of their leaves and, in the presence of sunlight, spin carbon dioxide together with water was awesome to me.

With the aid of cytochrome transport systems and leaping electrons, plants undertake an exquisitely beautiful act of biochemical self-creation. They make themselves. They exhale oxygen. And they feed us all.

The biological phenomenon of photosynthesis gave me a sense of ancestry.

By the time I went to college, I had discovered two things: 1) My ear for music was much better than my execution, which was not great; 2) I really loved trees.

So, I forsook the piano for plant ecology and, for my PhD research I learned the skills of dendrochronology, which allowed me to reconstruct the centuries-long history of a forest by studying the patterns of tree rings inside the heartwood of 200-year-old red pines.

The inside of a tree is a living scroll that tells the story—if you are trained to read the language of xylem and phloem—of the entire ecosystem. You can learn, for example, which years great forest fires swept through or which years had especially long winters. I became a historian of forests by studying the rings of the deep inside the trunks of individual trees.

I would have liked nothing better than to spend my life studying trees. But the acceleration of the climate crisis is now torching forests around the world. And drowning them with saltwater. And ravaging them with emergent diseases. And driving their pollinators into extinction. And otherwise stressing them to the point where they can no longer remove and sequester carbon dioxide from the air around them.

So, that’s why I became a civil disobedient with the Summer of Heat campaign. My responsibility as a plant biologist in this moment in human history is to do more than just teach photosynthesis and praise trees. All the oxygen we breathe is provided to us by plants, and they are in trouble. And governments aren’t acting. And banks like Citi keep on financing new fossil fuel projects that are ravaging ecosystems.

For me, the extraordinary concert we are about to witness is the place where botany and music come together.

Orchestral instruments like cellos and violins—as well as the bows drawn across their strings—are made from trees. And not just any trees but tree species that have what musicians call tonewood.

Pernambuco. Ebony. Certain species of maple and spruce.

These trees have cell walls with acoustical properties that vibrate in certain frequencies and, if they are all uniform in size and density, provide the richness of sound that we experience as musical. Different woods have different resonant qualities due to the ratio of cellulose and lignan. Typically, trees used to make classicial musical instruments are 200-400 years old with 20-inch trunks and tree rings that show slow and steady growth.

In a warming climate, however, annual growth rings have become less consistent in size, and the wood has become softer. Instrument-making trees are also increasingly targeted by emerging insect pests.

Trees with tonewood are now growing in more extreme weather conditions and enduring more frequent droughts. Those conditions alter their cellular architecture in ways that alter the tonal qualities of the wooden soundboards of the musical instruments made from their wood. As a result, orchestral music will sound different in the future. Of all things central to our humanity that climate change threatens, music is on the list.

Fifty years ago, playing a Chopin nocturne had the power to stop me from self-injuring. Listening to my friend John Mark Rozendaal defy Citi’s attempt to silence peaceful protest again the financing of climate ruin by performing Bach’s “Suites for Cello” will, I believe, have the power to call us all to stop injury to the planet.