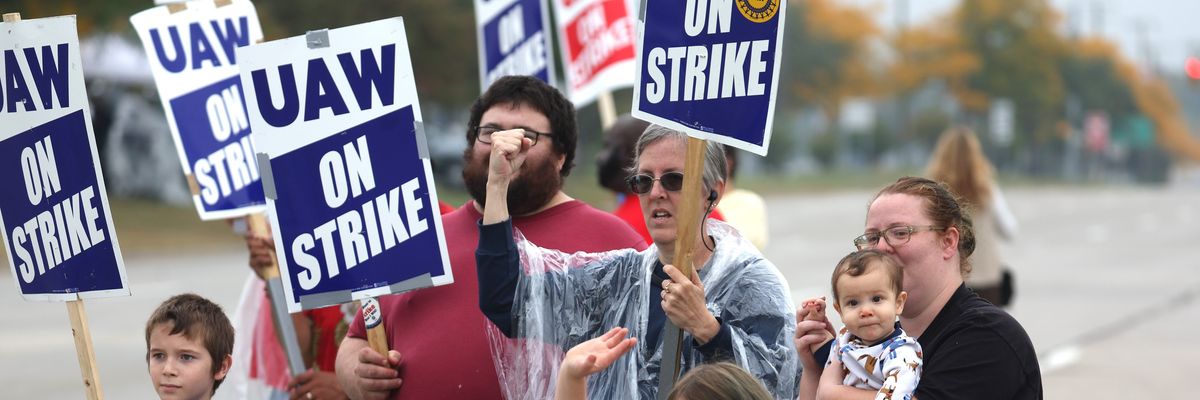

Organized labor and the climate movement—often portrayed as opponents—have made an auspicious start toward cooperation in the autoworkers strike. The UAW, eschewing Trumpian blandishments to attack the transition to electrical vehicles (EVs), have instead endorsed the transition to climate-safe cars and trucks.

One hundred climate organizations, rejecting the blandishments of auto industry allies that low wages in the non-union South will make EVs cheaper and therefore help fight global warming, have instead signed a letter of solidarity with UAW workers and are organizing to support union picket lines. The purpose of this Commentary is to explain the context of this convergence and to indicate the elements of a “just transition” for the auto industry that can provide a joint program for the labor and climate movements.

The Backstory

Mr.

Ross Gelbspan talked about his new book,

The Heat is On: The High Stakes Battle over Earth’s Threatened Climate. The book is about the science, economics and politics of global warming. Mr. Gelbspan argues that there is evidence that global warming is taking place all over the globe and that energy businesses are trying to hide the damage that fossil fuels have caused to the ozone layer.

Labor and climate issues have been entwined in the US auto industry since long before the public recognition of global warming. The Big Three auto strike is intertwined with the business and political strategy of the auto industry, its response to the climate crisis, the changing role of federal and state governments, and the decay and transformation of the UAW.

An investigative report by E&E News in 2020 found that company scientists warned executives at General Motors and Ford in the 1960s that carbon emissions from their cars and trucks would cause the earth’s climate to warm. In response to this threat, the auto companies secretly gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to organizations denying the reality of global warming. Along with the oil industry and the US National Association of Manufacturers they formed the Global Climate Coalition to oppose any mandatory actions to address global warming; it spent tens of millions of dollars on advertising against international climate agreements and national climate legislation. The auto companies expanded their investments in high-emission trucks and SUVs. They opposed higher standards for fuel economy and carbon emissions. Until 1996 the Big Three did not produce a single commercial electric vehicle – allowing Tesla to corner the market with its EVs. Today emissions from the tailpipes of cars and trucks are the largest source of greenhouse gas pollution in the United States.

In 2008, rising gas prices and the Great Recession devasted the Big Three’s carefully cultivated market for gas guzzlers. GM and Chrysler went into bankruptcy and an $81 billion bailout left the US government as majority owner of GM and the UAW and Fiat as the principal owners of Chrysler.

The US auto industry was reconstructed under President Barak Obama’s economic recovery plan. Auto corporations and the UAW agreed to a large, long-term increase in energy efficiency to cut carbon emissions. The auto corporations agreed to cooperate with emission reduction requirements because their survival depended on the plan’s massive public investment in the auto industry. This involved cooperative planning for retooling the industry, large-scale federal support for developing new technology, and substantial public investment in modernizing the industry on a low-carbon basis. The result was a steady decrease in carbon pollution rates, an increase of jobs for auto workers, and an end to the crisis that threated to nearly eliminate auto production – and an estimated three million jobs — in the United States.

Faced with the collapse of the auto industry and the loss of millions of jobs, the UAW had little choice but to agree to major concessions. Its contracts incorporated a two-tiered wage structure under which those hired through 2007 are now making an average of $33 per hour while those hired after 2007 now make $17 per hour or less. Lower-tier employees receive lower health benefits and don’t get defined benefit pensions or retiree health care. Auto workers lost the cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) that gave them protection against inflation. Nonetheless they went for years without wage increases. They also lost the “job banks” jobs security program that provided laid-off workers pay and benefits if employment dipped below a pre-defined level.

While the concessions were presented as a temporary measure to address the crisis in the auto industry, they were not reversed in subsequent contracts, and the degradation of auto work has continued to the present day. Meanwhile, the auto companies have continued to oppose climate protection policies and to promote high-pollution, low-mileage trucks and SUVs. Indeed, as recently as July 2023 the auto industry’s largest lobbying organization came out against the Biden administration’s proposed rule to ensure that two-thirds of new passenger cars sold in the United States are all-electric by 2032.

Subsidizing Change in the Auto Industry – At the Expense of Auto Workers and the Climate?

The politics of climate and jobs was transformed in 2019 by the proposal – initiated by the youth climate

Sunrise Movement and Representative

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – for a

Green New Deal. They called for a ten-year mobilization of every aspect of American society to create 100% clean and renewable energy, guarantee living-wage jobs for anyone who needs one, and a just transition for both workers and frontline communities. The Green New Deal reconfigured American politics with its core proposition: fix joblessness and inequality by putting people to work at good jobs fixing the climate.

Joe Biden’s presidential campaign created a committee stocked with Green New Deal advocates like Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders. He made their recommendations the centerpiece of his campaign policy. Biden’s Build Back Better plan combined ideas from the Green New Deal with proposals for “industrial policy” – government efforts to shape the economy by supporting specific industries, firms, or economic activities — long advocated by industrial unions and some progressive politicians. Many of these ideas were incorporated into Biden’s three major economic bills, the American Rescue Plan, Bipartisan Infrastructure, and Inflation Reduction Acts, which provide trillions of dollars over the next decade to incentivize domestic production in targeted industries, notably the auto industry. Unlike the government-led reconstruction of the auto industry under Obama, however, today’s federal program is largely limited to providing subsidies to auto companies to expand EV production, rather than actively reshaping the industry. When the House passed its version of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2021, it included another $4,500 tax credit to consumers for EVs built largely with union labor, but Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia succeeded in removing the provision as a condition for allowing the IRA to pass the Senate.

The auto companies have been happy to accept these federal subsidies, but they are also happy to evade their stated purposes. Auto companies have given surface compliance to federal pressure to reduce carbon pollution, but in reality they continue to promote highly profitable but high-carbon SUVs and light trucks and drag their feet on shifting to EVs. And they are using the federal subsidies to move their operations to low-wage, non-union locations in the South and to use joint ventures with foreign auto companies to evade unionization.

Since the early 1990s the South’s share of auto industry employment has grown from 15 to 30 per cent while the Midwest’s proportion has fallen from 60% to 45%. The auto companies are now using the subsidies provided by Biden’s industrial policy to accelerate this migration. In the past two years the big auto companies have announced nearly $90 billion in investment for EV plants, according to the Center for Automotive Research. Their suppliers are investing billions more. Brookings Metro says total private-sector investment in EV manufacturing under Biden has reached nearly $140 billion.

Brookings Metro calculated that the South has attracted 55 percent of the total private investment in electric vehicles and batteries under Biden, twice as much as has gone to the Midwest. Such EV and battery plant investments include Hyundai and Rivian in Georgia, Toyota in North Carolina, Tesla in Texas, BMW in South Carolina, Mercedes-Benz in Alabama, General Motors in Tennessee, and Ford in Tennessee and Kentucky. EV investments in the South are expected to create at least 65,000 jobs.

To further bolster their resistance to worker demands, auto companies are creating their EV battery plants as joint ventures with foreign companies. As such they are not subject to the master agreements that cover the Big Three, so that the UAW must negotiate separate contracts for plants that are already offering wages far below the master agreements.

This “restructuring” seemed to be just fine with the Biden administration. In early June Energy Secretary Jennifer Grandholm told an industry group that the administration was “agnostic” about where companies choose to site their clean-energy investments. Later that same month the Department of Energy approved more than $9 billion in loans to Ford and a Korean company to build EV battery plants in Kentucky and Tennessee. This subsidy gave no consideration to wages, working conditions, union rights, or retirement security. The next day UAW president Shawn Fain issued a statement that read in part:

The switch to electric engine jobs, battery production and other EV manufacturing cannot become a race to the bottom. Not only is the federal government not using its power to turn the tide – they’re actively funding the race to the bottom with billions in public money. Why is Joe Biden’s administration facilitating this corporate greed with taxpayer money?

In the past five years, workers who build GM products in Lordstown Ohio, have had their lives turned upside down as they were forced to retire, quit or uproot their families and move all over the United States when GM closed their plants despite massive profits. Their jobs were replaced in GM’s new joint-venture battery facility with jobs that pay half of what workers made at the previous Lordstown plant.

Not only is the White House refusing to right this wrong, they’re giving Ford $9.2 billion to create the same low-road jobs in Kentucky and Tennessee.

The last time the federal government gave the Big Three billions of dollars, the companies did the exact same thing: slash wages, cut jobs, and undermine the industry that for generations created the best jobs for working families in this country. Autoworkers and our families took the hit in 2009 in the name of saving the industry. We were never made whole, and it’s an absolute shame to see another Democratic administration doubling down on a taxpayer-funded corporate giveaway.

Faced with such a rebuff in the prelude to the impending auto strike, and perhaps counting the working class voters in a state critical for the 2024 presidential election, the Biden administration announced in late August that the Energy Department would provide $2 billion in grants and $10 billion in loan guarantees under the Inflation Reduction Act, plus $3.5 billion in grants under the infrastructure law, to help companies convert existing plants to making EVs and batteries. The once-“agnostic” Granholm proclaimed her new religion: “We are going to focus on financing projects that are in long-standing automaking communities, that keep folks already working on the payroll, projects that advance collective bargaining agreements, that create high-paying, long-lasting jobs.”

UAW president Fain praised the decision.

The UAW supports and is ready for the transition to a clean auto industry. But the EV transition must be a just transition that ensures auto workers have a place in the new economy. Today’s announcement from the Department of Energy echoes the UAW’s call for strong labor standards tied to all taxpayer funding that goes to auto and manufacturing companies. This new policy makes clear to employers that the EV transition must include strong union partnerships with the high pay and safety standards that generations of UAW members have fought for and won.

The Biden administration’s shift – at least momentarily – toward a just transition for auto workers facing the greening of their industry indicates both the political popularity of just transition and a balance of forces propitious for efforts to realize it. Given that context, what measures can labor and climate movements advocate to begin to realize a just transition for auto workers?

A Just Transition for Auto Workers

The UAW, more than a hundred climate and allied organizations, and President Joe Biden have all endorsed a “just transition” to electric vehicles for auto workers. But what would a just transition for auto workers actually mean? Here are some of the measures that workers, environmentalists, and governments could join together to promote.

Union demands

In contrast to past negotiations with the Big Three, the current UAW leadership has presented its basic proposals both to auto workers and to the public. In addition to wage and other economic demands, there are three union proposals in particular that are necessary parts of a just transition.

- Working family protection program: Until 2009 the Big Three had a “job banks” jobs security program. If employment dipped below an agreed level, laid-off workers would receive pay and benefits. The UAW is proposing an updated version, the “Working family protection program,” which would require companies that shut down facilities to pay UAW members to do community-service work. It would give the companies a strong incentive to keep plants open and workers on the job.

- Right to strike over plant closures. The Big Three have closed 65 plants over the last 20 years. Yet workers and communities are often powerless in the face of shutdowns. The right to strike over plant closures will provide a powerful tool to deter them and to provide workers and community members power to negotiate just terms for closures.

- Eliminating tiers. In 2008 when the collapse of the US auto industry threatened to destroy as many as three million jobs, the UAW agreed to major concessions, including separation of workers into “tiers” which provided far lower wages and worse conditions for workers who were newly hired. The companies have used this to divide the workforce and to drive down wages for the growing proportion of lower seniority workers. As long as the tier system persists, the companies will be able to discriminate against a growing proportion of the workforce. Getting rid of tiers is an essential part of a just transition because the companies can use them to drive down conditions for workers making electric vehicles. The Teamsters’ recently ended tiers at UPS.

Federal policy

- Just Transition requirements in federal auto subsidies. Initially funding under the Inflation Reduction Act and other federal programs that subsidize the transition to climate-safe industry did little to see that the jobs created would be good jobs, let alone union jobs. As a result, the auto companies have been taking the subsidies and using them to shut down good-paying union jobs in the Midwest and open new, nonunion jobs with lower pay and dangerous health and safety conditions in southern states with anti-labor “right-to-work” laws.

When the UAW protested, the Biden administration changed course and issued a $15.5 billion package of grants and loans primarily focused on retooling existing factories for the transition to EVs. This package included conditions for grants and loans that, if applied across the board to all EV subsidies, would make a major contribution to a just transition for auto workers.

In the $2 billion Domestic Conversion Grant Program, higher scores will be given to “projects that are likely to retain collective bargaining agreements and/or those that have an existing high-quality, high-wage hourly production workforce, such as applicants that currently pay top quartile wages in their industry.” The program “aims to support a just transition for workers and communities in the transition to electrified transportation,” with particular attention to “communities supporting facilities with longer histories in automotive manufacturing.” Preference will be given to projects that “commit to pay high wages for production workers and maintain collective bargaining agreements.”

The Department of Energy’s recent $10 billion loan initiative under the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program for automotive manufacturing conversion projects is targeted for automotive manufacturing conversion projects that “retain high-quality jobs in communities that currently host manufacturing facilities.” Examples of criteria include “retaining high wages and benefits, including workplace rights, or commitments such as keeping the existing facility open until a new facility is complete, in the case of facility replacement projects.”

These programs were welcomed by UAW president Shawn Fain. Their provisions will make it difficult for auto companies to take the money and use it to shut down existing union plants and open new nonunion plants in low-wage regions.

So far, these conditions apply only to a tiny sliver of the hundreds of billions of dollars that the federal government plans to give or induce others to invest in the transition to electric vehicles. They do not currently apply to other grants and loans. And they do not apply to the many times larger subsidies that will be given via tax credits. The Advance Manufacturing Tax Credit, for example, requires minimums for domestic content, payment of prevailing wages, and apprenticeship-based training. But it says nothing about location or workers’ right to union representation or collective bargaining.

A crucial strategy for a just transition for auto workers could be to include labor requirements in all EV subsidies similar to those in the recent package of grants and loans. Their inclusion in already established programs makes a strong case that they are legal and proper policies.

- Community Benefit Plans. The Department of Energy is requiring Community Benefits Plans in all funding opportunity announcements and loan applications under the Bipartisan Infrastructure and Inflation Reduction Acts. Its Community Benefits Plans are based on four core policy priorities: investing in America’s workforce; engaging communities and labor; advancing diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility; and implementing Justice 40. A core purpose of the Community Benefit Plans is “engaging communities and labor.” Auto workers and communities can use this as an opportunity for demanding that such plans in fact address the needs of existing auto workers and communities. For example, labor and climate coalitions could demand that there by no layoffs of current workers in facilities that use the grants and loans.The requirement for Community Benefits Plans can and should be extended to all BIA and IRA grants and loans.

- Employee Retention Credits. The 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) provides for an employee retention tax credit designed to encourage employers to keep employees on their payroll despite experiencing an economic hardship related to COVID-19. Some or all of the federal tax credits allocated for the transition to EVs could be redesigned to similarly incentivize auto companies to retain current workers.

State policy

- Just Transition Programs: Legislation recently submitted to the Michigan legislature has proposed a state program for just transition, modeled in part on the just transition legislation now in operation in Colorado. An early version of the Michigan bill establishes a broad-based advisory committee to draft a community and worker economic transition plan. It would establish a wage differential benefit for affected workers, provide education for dislocated workers, and create a grant program to support transitional communities.

- Job Criteria in State Subsidies. A wide array of state programs could incorporate criteria like those indicated above for federal programs. For example, economic development grants could be targeted for investments in existing auto communities to encourage conversion of existing plants and/or building of new plants for EV production.

- State Employee Retention Credits. Discussion is under way in some midwestern state legislatures to enact state employee retention credits along the lines of those in the federal CARES act.

These state programs might be most effective if they were coordinated among the states of the Midwest auto region.

These just transition proposals are not “pie in the sky.” They grow out of existing programs and proposals of the UAW, the climate movement, federal agencies, and state legislators. As President Biden’s unprecedented decision to join the UAW picket line indicates, they come at a time when the government and the auto companies are most vulnerable to pressure to do the right thing. They will not in themselves turn the auto plants into a utopia. But they can play a significant role in halting and even reversing the race to the bottom that is already underway in the auto industry. They can promote both climate protection and a decent future for auto workers. And they can provide a program around which auto workers, climate protectors, and advocates for the public interest can join forces.

Read the original version of this post, along with footnotes, at the Labor Network for Sustainability website here.