Cutting to the chase—on January 12, 2018, Robert Cooper, senior vice president of engineering and construction for the Mountain Valley Pipeline,

testified in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia. This part of his testimony (on p. 101) came right after a map of MVP’s route was entered into evidence.

Q: “What is the purpose of this pipeline?”

A: “This pipeline’s purpose is to connect gas supplies, predominantly in southwestern Pennsylvania and north central West Virginia, with other markets in the country by traversing the route that’s shown and connecting into Transco’s interstate system. And from there, the suppliers or owners of the gas can market it to the various markets up and down the Eastern Seaboard and over to the Gulf Coast or into Florida.”

Then on pages 102-103:

Q: “And you mentioned the final termination point is Transco. Can you explain what that is please?”

A: “That’s correct. There’s station 165 in Pittsylvania County. There are several pipelines that connect the gas system up toward the Eastern Seaboard of the country and can also traverse gas backwards. Ultimately, it can go all the way to Texas-Louisiana—you know, those other areas where there are demand centers, like industrial demand, or demand for power generation.

“There’s also interconnects with other pipelines that could carry the gas to Florida as well.”

There are a lot of reasons, legal and otherwise, to fight MVP.

Bill McKibben recently wrote an important

article in The New Yorker titled “The Biden Administration’s Next Big Climate Decision,” subtitled, “The liquefied-natural-gas buildout—and fossil-fuel exports—challenge progress on global warming.”

It explains why the proposed large scale buildout of U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals will be a monumental mistake regarding climate change and also lead to increased costs for American consumers. McKibben reports that the Biden administration may be deciding the fate of the largest of these terminals, CP2, or Calcasieu Pass 2, this fall.

Right now there’s an LNG export terminal in Maryland, another one in Georgia, three in Louisiana, and two in Texas.

According to the most current (July 2022) map shown on the Department of Energy’s website, there are plans to build at least 23 more, 14 of which have already been approved—six in both Louisiana and Texas, along with one in Florida and another in Mississippi. Seven more in LA and two more in Texas have been proposed but not yet approved.

That’s a total of 30 LNG export terminals up and down the Eastern Seaboard, from Maryland to Florida and across the Gulf Coast to Texas, all of which, according to Robert Cooper’s testimony, MVP will be able to help feed. Perhaps that is why such an extra large (42-inch diameter), extra expensive pipeline was proposed in the first place.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the Marcellus shale play in the Appalachian Basin, spanning Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, is the

largest source of natural gas from shale in America. The American Petroleum Institute says Marcellus shale is estimated to be the second largest natural gas find in the world.

MVP, like LNG and CP2, is a climate disaster. It also presents an enormous safety risk. It’s being built

up and down steep slopes where landslides have already occurred. There will be more when an unprecedented rain event, the kind we see so often these days, parks itself over the area someday. The coating on MVP pipe that is suppose to protect it from corrosion is defective, due to sitting out in the sun for 6 to 7 years, which is 10-12 times longer than the National Association of Pipe Coating Applicators (NAPCA) recommends.

This is how fusion bonded epoxy (FBE) corrosion-proof coating is suppose to look.

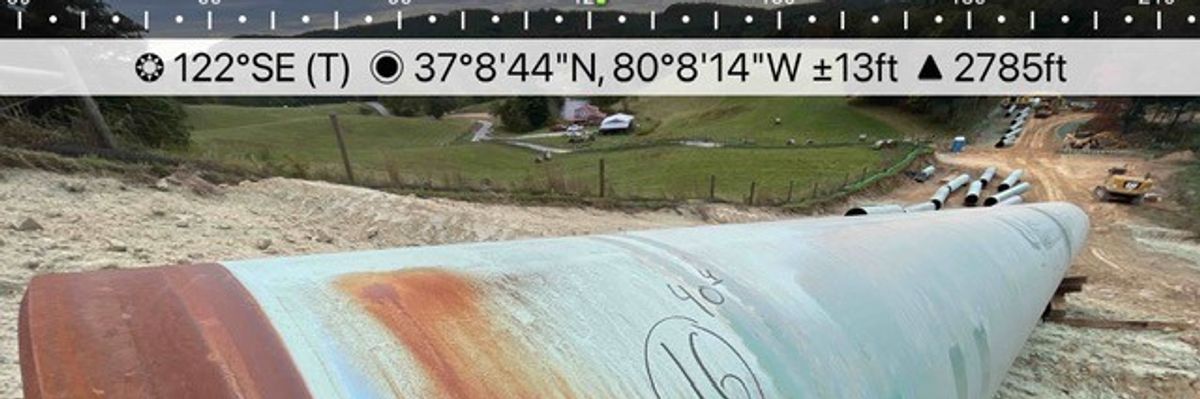

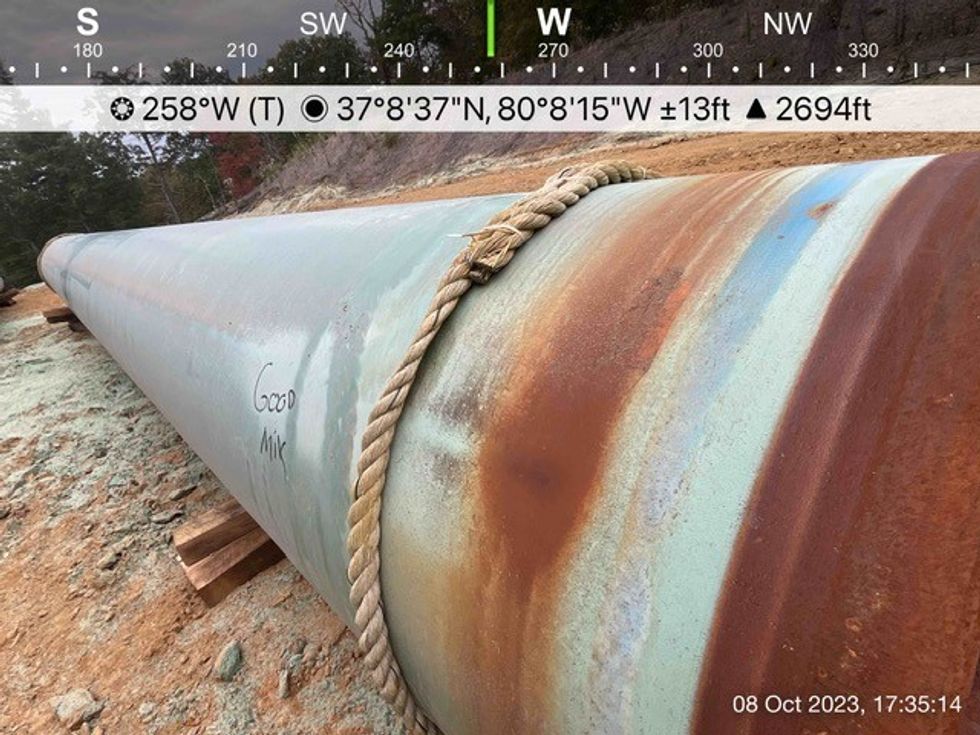

This is how degraded, illegal MVP corrosion-proof coating looks in October 2023 after sitting out in the sun for over six years, which is ten times longer than the coating manufacturer recommends.

As MVP gets built, huge pieces of pipe are moved around and set in place. Each time this happens, they flex. Because the coating is old and brittle, it no longer flexes with the pipe. And so, it cracks. We know this because Keystone XL (KXL) pipe, which also sat out in the sun for years, and was manufactured and coated by the same company as MVP pipe was, had its coating tested. Every single KXL sample that underwent a flexibility test cracked (p. 19). And cracked coating isn’t just unsafe. It’s also illegal, precisely because it’s unsafe. In order to be legal, corrosion-proof coating MUST be “sufficiently ductile (meaning flexible) to resist cracking”.

This photo shows degraded MVP pipe coating with a gouge that exposes bare steel.

This photo shows degraded MVP pipe coating with a gouge that exposes bare steel.

Even Robert Cooper, during his testimony 69 months ago (p. 134), said that pipe needed to get in the ground soon to protect the coating from the sun. Of course then it was an argument for quickly taking land via eminent domain from property owners who were unwilling to sell.

MVP will operate under extremely high pressure. When a landslide breaks it apart or premature corrosion causes a rupture as gas is propelled full throttle on its way to an LNG terminal, it will be like nothing we have seen before. MVP doesn’t just go up and down steep mountains. It goes by people’s houses and their children’s schools. Given that it took Equitrans, the company building MVP, 13 days to stop last year’s biggest climate disaster, there’s no trust that they’re on top of any situation. Their climate disaster, by the way, was an out-of-control methane leak caused by… corrosion.

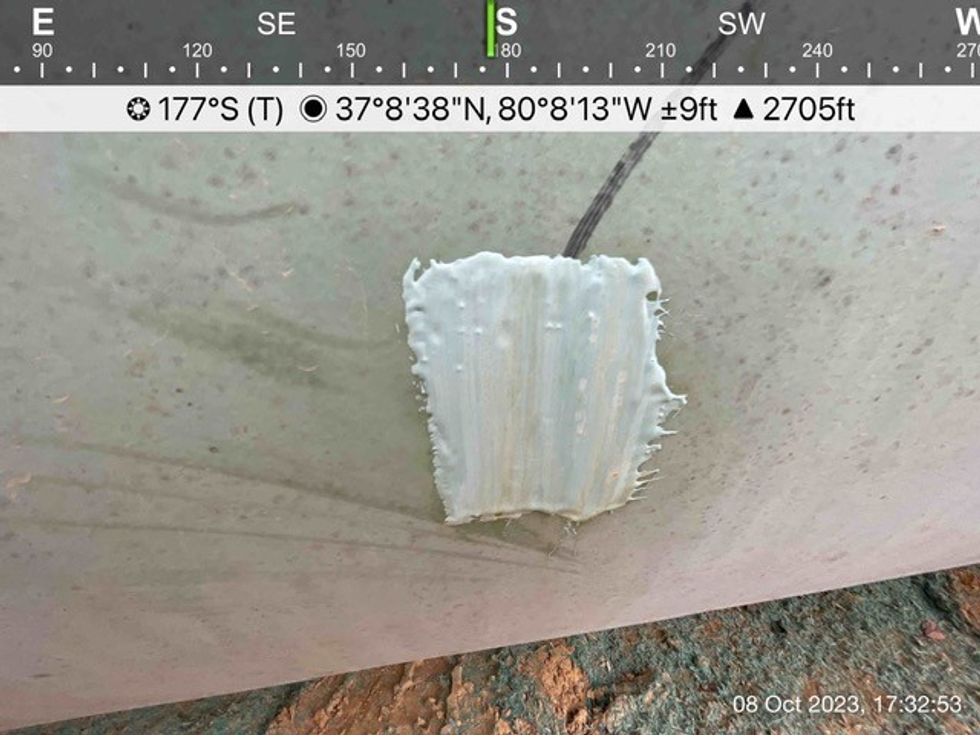

This photo shows how a gouge on MVP pipe was patched in a wholly inadequate manner.

This photo shows how a gouge on MVP pipe was patched in a wholly inadequate manner.

The debt deal was a dirty deal, but it didn’t make MVP a done deal. They may be arresting protesters, but it is MVP that’s burying illegal pipe. There are a lot of reasons, legal and otherwise, to fight MVP. Bill McKibben’s article coupled with Robert Cooper’s testimony just gave us one more.

This photo shows degraded MVP pipe coating with a gouge that exposes bare steel.

This photo shows degraded MVP pipe coating with a gouge that exposes bare steel. This photo shows how a gouge on MVP pipe was patched in a wholly inadequate manner.

This photo shows how a gouge on MVP pipe was patched in a wholly inadequate manner.