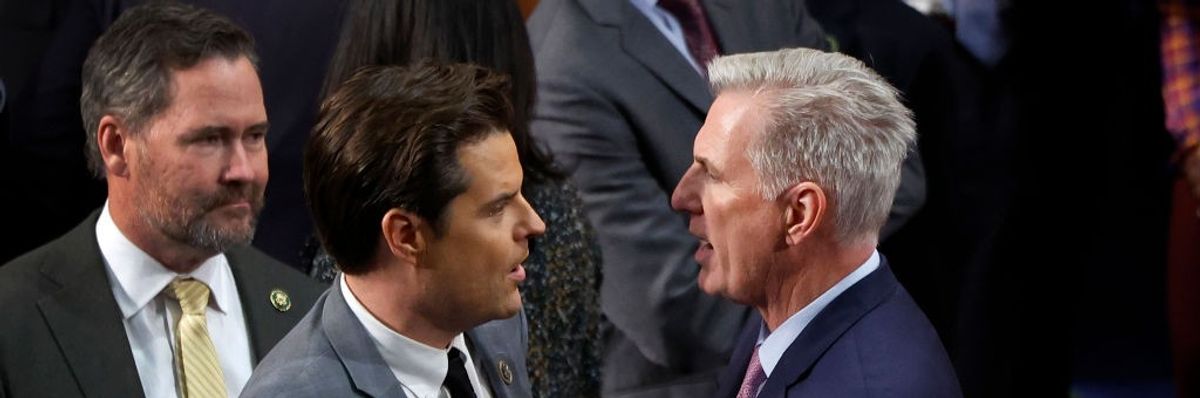

U.S. House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) talks to Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) in the House Chamber after Gaetz voted present during the fourth day of voting for Speaker of the House at the U.S. Capitol Building on January 06, 2023 in Washington, DC.

McCarthy's GOP Cruelly Targets Most-Vulnerable With Sabotage of US Economy as Hostage

No one who actually wants to reduce the federal deficit should be looking to do that on the backs of the poorest and most vulnerable Americans.

This week, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy plans to hold a vote on a bill that would raise the nation’s debt limit, but only in conjunction with extraordinarily steep spending cuts and new barriers to accessing income support programs. This is the next milestone in House Republicans’ attempt to play a game of dangerous political brinkmanship with the U.S. economy, trying to force through harmful and deeply unpopular federal spending cuts in exchange for increasing the debt limit. This approach recklessly flirts with bringing on the economic catastrophe of a government default in the short term.

Speaker McCarthy’s proposal would slash spending across federal programs for the next decade, cutting federal resources for everything from child care programs to environmental protection safeguards. If these deeply unrealistic spending cuts actually came to pass, the human toll would be enormous, and economic growth would be deeply damaged.

The McCarthy proposal also resurfaces a completely inaccurate but alarmingly persistent conservative claim: the idea that government anti-poverty programs are unnecessarily generous, bloated, and are keeping people out of the workforce who should otherwise be supporting themselves entirely through income earned in the labor market. The proposal seeks to severely restrict access to Medicaid health coverage and food stamps by imposing onerous requirements to prove that recipients are working or looking for work. Past evidence about these types of burdensome reporting requirements shows clearly that they will not actually lead to increased employment but will deprive vulnerable families of vital support.

Income support programs are not keeping people out of the workforce

The implicit claim that the U.S. labor market is hobbled by a too-generous welfare state is awfully hard to see in the data. Job growth in 2021 and 2022 hit its highest two-year stretch in the nation’s history. The unemployment rate is currently at a near-historic low. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio hit its highest point in March 2023 in more than 20 years. In general, many low-wage workers have seen the benefits of a tight labor market in the pandemic recovery, as employers have raised wages to attract and retain workers. In short, when jobs are available, workers have rushed to fill them. And while food assistance programs and other safety net supports are a vital lifeline to keep many out of poverty, the benefits are nowhere near enough on their own to fully support the cost of living for many families. Where has the idea come from that there’s an urgent need to address these supposedly too-comfortable benefits keeping people out of the workforce?

The premise of adding more onerous work and reporting requirements is also based on an inaccurate picture of who currently receives federal assistance through these programs. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently noted, nearly two-thirds of adults with Medicaid already work. Since the early 2000s, many safety net and income support programs have actually shifted toward requiring proof that recipients are also working or looking for work, but the gains of this shift have been near-impossible to see in terms of increased employment. Since 1990, all new investments in safety net spending have gone toward families with at least some labor market earnings. Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

The U.S. safety net is in serious need of reforms, but not because of inaccurate claims that its excess generosity keeps people out of work. Public spending in the United States as a share of GDP is extremely low relative to other rich nations, and we spend far less to fight poverty than other comparatively wealthy countries. Low-income people already spend a ridiculous amount of energy attempting to prove and maintain their eligibility for these modest supports.

Imposing additional “work requirements” would restrict access to Medicaid and food stamps

Burdensome work reporting requirements are about making the benefits system more sluggish and difficult to access, and do nothing to boost employment. Existing reporting requirements already impose too-high a bureaucratic burden to accessing needed help. Passing these more burdensome requirements being called for by Speaker McCarthy would require people in need of assistance to devote even more of their bandwidth to dealing with forms and make-work bureaucratic tasks, rather than spending that time and energy looking for good work in meaningful and productive ways. The solution should be to reduce the amount of “means-testing” required and to make programs more readily accessible, not to restrict them further.

The biggest problem with the U.S. safety net is that our programs don’t help as many people, or as effectively, as they should.

Further, Speaker McCarthy’s claims that this proposal would put the United States on a path to “fiscal responsibility” and lower inflation are laughable. The biggest driver of deficits for the last 20 years has been a steady trend toward ever-larger tax cuts for corporations and the richest U.S. households. No one who actually wants to reduce the federal deficit should be looking to do that on the backs of the poorest and most vulnerable Americans.

The strongest “incentive” that people have to enter or reenter the workforce already exists—they need income to survive and provide for themselves and their families. If they’re not already working but want to, there is likely a very good reason. Many people simply can’t afford or access quality child care, or quality care for other family members, and need to take on those responsibilities themselves rather than entering the paid workforce. People with disabilities may struggle to find jobs that accommodate their needs appropriately, or that provide adequate health coverage. Many can’t find jobs with the fair and predictable scheduling they need. Others may stay out of the workforce because of a persistent lack of economic opportunities available in their neighborhoods, towns, or cities—a lack of opportunity often caused by systemic public and private disinvestment in communities of color or rural areas.

Any policymaker serious about getting people who want to work into the workforce should be looking to address these problems, rather than taking away lifelines to food and health care.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This week, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy plans to hold a vote on a bill that would raise the nation’s debt limit, but only in conjunction with extraordinarily steep spending cuts and new barriers to accessing income support programs. This is the next milestone in House Republicans’ attempt to play a game of dangerous political brinkmanship with the U.S. economy, trying to force through harmful and deeply unpopular federal spending cuts in exchange for increasing the debt limit. This approach recklessly flirts with bringing on the economic catastrophe of a government default in the short term.

Speaker McCarthy’s proposal would slash spending across federal programs for the next decade, cutting federal resources for everything from child care programs to environmental protection safeguards. If these deeply unrealistic spending cuts actually came to pass, the human toll would be enormous, and economic growth would be deeply damaged.

The McCarthy proposal also resurfaces a completely inaccurate but alarmingly persistent conservative claim: the idea that government anti-poverty programs are unnecessarily generous, bloated, and are keeping people out of the workforce who should otherwise be supporting themselves entirely through income earned in the labor market. The proposal seeks to severely restrict access to Medicaid health coverage and food stamps by imposing onerous requirements to prove that recipients are working or looking for work. Past evidence about these types of burdensome reporting requirements shows clearly that they will not actually lead to increased employment but will deprive vulnerable families of vital support.

Income support programs are not keeping people out of the workforce

The implicit claim that the U.S. labor market is hobbled by a too-generous welfare state is awfully hard to see in the data. Job growth in 2021 and 2022 hit its highest two-year stretch in the nation’s history. The unemployment rate is currently at a near-historic low. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio hit its highest point in March 2023 in more than 20 years. In general, many low-wage workers have seen the benefits of a tight labor market in the pandemic recovery, as employers have raised wages to attract and retain workers. In short, when jobs are available, workers have rushed to fill them. And while food assistance programs and other safety net supports are a vital lifeline to keep many out of poverty, the benefits are nowhere near enough on their own to fully support the cost of living for many families. Where has the idea come from that there’s an urgent need to address these supposedly too-comfortable benefits keeping people out of the workforce?

The premise of adding more onerous work and reporting requirements is also based on an inaccurate picture of who currently receives federal assistance through these programs. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently noted, nearly two-thirds of adults with Medicaid already work. Since the early 2000s, many safety net and income support programs have actually shifted toward requiring proof that recipients are also working or looking for work, but the gains of this shift have been near-impossible to see in terms of increased employment. Since 1990, all new investments in safety net spending have gone toward families with at least some labor market earnings. Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

The U.S. safety net is in serious need of reforms, but not because of inaccurate claims that its excess generosity keeps people out of work. Public spending in the United States as a share of GDP is extremely low relative to other rich nations, and we spend far less to fight poverty than other comparatively wealthy countries. Low-income people already spend a ridiculous amount of energy attempting to prove and maintain their eligibility for these modest supports.

Imposing additional “work requirements” would restrict access to Medicaid and food stamps

Burdensome work reporting requirements are about making the benefits system more sluggish and difficult to access, and do nothing to boost employment. Existing reporting requirements already impose too-high a bureaucratic burden to accessing needed help. Passing these more burdensome requirements being called for by Speaker McCarthy would require people in need of assistance to devote even more of their bandwidth to dealing with forms and make-work bureaucratic tasks, rather than spending that time and energy looking for good work in meaningful and productive ways. The solution should be to reduce the amount of “means-testing” required and to make programs more readily accessible, not to restrict them further.

The biggest problem with the U.S. safety net is that our programs don’t help as many people, or as effectively, as they should.

Further, Speaker McCarthy’s claims that this proposal would put the United States on a path to “fiscal responsibility” and lower inflation are laughable. The biggest driver of deficits for the last 20 years has been a steady trend toward ever-larger tax cuts for corporations and the richest U.S. households. No one who actually wants to reduce the federal deficit should be looking to do that on the backs of the poorest and most vulnerable Americans.

The strongest “incentive” that people have to enter or reenter the workforce already exists—they need income to survive and provide for themselves and their families. If they’re not already working but want to, there is likely a very good reason. Many people simply can’t afford or access quality child care, or quality care for other family members, and need to take on those responsibilities themselves rather than entering the paid workforce. People with disabilities may struggle to find jobs that accommodate their needs appropriately, or that provide adequate health coverage. Many can’t find jobs with the fair and predictable scheduling they need. Others may stay out of the workforce because of a persistent lack of economic opportunities available in their neighborhoods, towns, or cities—a lack of opportunity often caused by systemic public and private disinvestment in communities of color or rural areas.

Any policymaker serious about getting people who want to work into the workforce should be looking to address these problems, rather than taking away lifelines to food and health care.

- 'What Did McCarthy Promise?' Concerns Raised Over Backroom Deals With GOP Extremists ›

- 'This Scam Is a Non-Starter': Dems Blast McCarthy's Latest Call for Painful Cuts ›

- Giving Away the Game, Gaetz Says McCarthy 'Picked Up' Far-Right's Debt Ceiling Plan ›

- Senior Groups Tell Kevin McCarthy to 'Release His Hostage' and Back Clean Debt Ceiling Hike ›

- Sanders Calls on Biden to Fight for Working People as GOP Wages 'War' in Debt Limit Proposal ›

- Opinion | The GOP’s Sadistic Debt Limit Ploy Is a Direct Attack on People | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The GOP Has a Very Anti-American Agenda | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | GOP Debt Ceiling Bill Would Strip $1.3 Trillion From States and Local Communities | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | It’s Clear as Day the GOP Does Not Really Care About Debt or the Deficit | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | A Quarterly Report on the Economy for Working People | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Food Stamp Work Rules Harm Older, Poor Americans | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Kevin McCarthy, the Unprincipled Lout, Is Out. | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | We Know What Works to Fight Poverty—Now Let’s Do It | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | We Need to Work Together for a Stronger Safety Net | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | An Immigration Policy Rooted in Exclusion Represents the Worst of US Politics | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Economic Growth Is the World’s Most Dangerous Game | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The Only People Who Will Benefit From Slashing the Federal Workforce Are the Rich | Common Dreams ›

This week, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy plans to hold a vote on a bill that would raise the nation’s debt limit, but only in conjunction with extraordinarily steep spending cuts and new barriers to accessing income support programs. This is the next milestone in House Republicans’ attempt to play a game of dangerous political brinkmanship with the U.S. economy, trying to force through harmful and deeply unpopular federal spending cuts in exchange for increasing the debt limit. This approach recklessly flirts with bringing on the economic catastrophe of a government default in the short term.

Speaker McCarthy’s proposal would slash spending across federal programs for the next decade, cutting federal resources for everything from child care programs to environmental protection safeguards. If these deeply unrealistic spending cuts actually came to pass, the human toll would be enormous, and economic growth would be deeply damaged.

The McCarthy proposal also resurfaces a completely inaccurate but alarmingly persistent conservative claim: the idea that government anti-poverty programs are unnecessarily generous, bloated, and are keeping people out of the workforce who should otherwise be supporting themselves entirely through income earned in the labor market. The proposal seeks to severely restrict access to Medicaid health coverage and food stamps by imposing onerous requirements to prove that recipients are working or looking for work. Past evidence about these types of burdensome reporting requirements shows clearly that they will not actually lead to increased employment but will deprive vulnerable families of vital support.

Income support programs are not keeping people out of the workforce

The implicit claim that the U.S. labor market is hobbled by a too-generous welfare state is awfully hard to see in the data. Job growth in 2021 and 2022 hit its highest two-year stretch in the nation’s history. The unemployment rate is currently at a near-historic low. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio hit its highest point in March 2023 in more than 20 years. In general, many low-wage workers have seen the benefits of a tight labor market in the pandemic recovery, as employers have raised wages to attract and retain workers. In short, when jobs are available, workers have rushed to fill them. And while food assistance programs and other safety net supports are a vital lifeline to keep many out of poverty, the benefits are nowhere near enough on their own to fully support the cost of living for many families. Where has the idea come from that there’s an urgent need to address these supposedly too-comfortable benefits keeping people out of the workforce?

The premise of adding more onerous work and reporting requirements is also based on an inaccurate picture of who currently receives federal assistance through these programs. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently noted, nearly two-thirds of adults with Medicaid already work. Since the early 2000s, many safety net and income support programs have actually shifted toward requiring proof that recipients are also working or looking for work, but the gains of this shift have been near-impossible to see in terms of increased employment. Since 1990, all new investments in safety net spending have gone toward families with at least some labor market earnings. Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

Those who are unable to find or do work under the current requirements are already in extremely difficult circumstances, and taking away the few safety net supports they have available would be economically devastating.

The U.S. safety net is in serious need of reforms, but not because of inaccurate claims that its excess generosity keeps people out of work. Public spending in the United States as a share of GDP is extremely low relative to other rich nations, and we spend far less to fight poverty than other comparatively wealthy countries. Low-income people already spend a ridiculous amount of energy attempting to prove and maintain their eligibility for these modest supports.

Imposing additional “work requirements” would restrict access to Medicaid and food stamps

Burdensome work reporting requirements are about making the benefits system more sluggish and difficult to access, and do nothing to boost employment. Existing reporting requirements already impose too-high a bureaucratic burden to accessing needed help. Passing these more burdensome requirements being called for by Speaker McCarthy would require people in need of assistance to devote even more of their bandwidth to dealing with forms and make-work bureaucratic tasks, rather than spending that time and energy looking for good work in meaningful and productive ways. The solution should be to reduce the amount of “means-testing” required and to make programs more readily accessible, not to restrict them further.

The biggest problem with the U.S. safety net is that our programs don’t help as many people, or as effectively, as they should.

Further, Speaker McCarthy’s claims that this proposal would put the United States on a path to “fiscal responsibility” and lower inflation are laughable. The biggest driver of deficits for the last 20 years has been a steady trend toward ever-larger tax cuts for corporations and the richest U.S. households. No one who actually wants to reduce the federal deficit should be looking to do that on the backs of the poorest and most vulnerable Americans.

The strongest “incentive” that people have to enter or reenter the workforce already exists—they need income to survive and provide for themselves and their families. If they’re not already working but want to, there is likely a very good reason. Many people simply can’t afford or access quality child care, or quality care for other family members, and need to take on those responsibilities themselves rather than entering the paid workforce. People with disabilities may struggle to find jobs that accommodate their needs appropriately, or that provide adequate health coverage. Many can’t find jobs with the fair and predictable scheduling they need. Others may stay out of the workforce because of a persistent lack of economic opportunities available in their neighborhoods, towns, or cities—a lack of opportunity often caused by systemic public and private disinvestment in communities of color or rural areas.

Any policymaker serious about getting people who want to work into the workforce should be looking to address these problems, rather than taking away lifelines to food and health care.

- 'What Did McCarthy Promise?' Concerns Raised Over Backroom Deals With GOP Extremists ›

- 'This Scam Is a Non-Starter': Dems Blast McCarthy's Latest Call for Painful Cuts ›

- Giving Away the Game, Gaetz Says McCarthy 'Picked Up' Far-Right's Debt Ceiling Plan ›

- Senior Groups Tell Kevin McCarthy to 'Release His Hostage' and Back Clean Debt Ceiling Hike ›

- Sanders Calls on Biden to Fight for Working People as GOP Wages 'War' in Debt Limit Proposal ›

- Opinion | The GOP’s Sadistic Debt Limit Ploy Is a Direct Attack on People | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The GOP Has a Very Anti-American Agenda | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | GOP Debt Ceiling Bill Would Strip $1.3 Trillion From States and Local Communities | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | It’s Clear as Day the GOP Does Not Really Care About Debt or the Deficit | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | A Quarterly Report on the Economy for Working People | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Food Stamp Work Rules Harm Older, Poor Americans | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Kevin McCarthy, the Unprincipled Lout, Is Out. | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | We Know What Works to Fight Poverty—Now Let’s Do It | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | We Need to Work Together for a Stronger Safety Net | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | An Immigration Policy Rooted in Exclusion Represents the Worst of US Politics | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Economic Growth Is the World’s Most Dangerous Game | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The Only People Who Will Benefit From Slashing the Federal Workforce Are the Rich | Common Dreams ›