My limbic system is down for repairs; week after week of record high temperatures around the globe, with fires blazing, reefs bleaching, ice sheets melting. It’s the biggest story on Earth, and I will go on working on it for the rest of my life, but today, for whatever reason, I found myself in need of something… not more cheerful but more meditative, something that engages a different part of my brain.

So I found it useful to spend a day watching and rewatching a short new film by the director dream hampton (she lowercases her name, in part in tribute to the beloved essayist bell hooks) about her home city of Detroit. hampton is a big-time movie-maker; her harrowing account of an abusive R&B star, Surviving R. Kelley, has gotten all kinds of awards. But perhaps her limbic system needed a break too; in any event, this video, made for the Times Op-Docs series (in conjunction with the remarkable folks at the Hip Hop Caucus), is in a very different key. It’s about the way that as the Great Lakes have risen in recent years they’ve begun to flood the Belle Isle section of Detroit, which as she explains in a study guide accompanying the video is a park rich in memories for her and “historically a gathering place for Black Detroiters’ family reunions, celebrations, or just sunny afternoons.”

Whenever I come home, one of the first things I do is go to Belle Isle. I just do a lap around the isle. It doesn’t matter what season it is. It could be the dead of winter, or it could be a crowded summer day. But that’s like a real grounding for me, you know. When I was growing up and when my daddy would come get me on the weekends, we would do a lap around Belle Isle in his ‘98. He always knew somebody in the park.

There’s been flooding in other parts of Detroit in recent years too, as rainstorms have gotten stronger, and much of the film is imagery of people’s basements, where stored memories end up soggy and mildewed. In the film she puts it like this:

The flooding eats your memories. It destroys them. It literally takes your old photographs, your prom dress, your father’s boots. When I think about flooding, I think about how when water is still, flooding is literally like water being trapped and having nowhere to go. Sometimes we don’t even have not just the energy, but the means to deal with flooding. I think about what’s about to happen to this whole region. I think about individuals’ basement, and what it means every spring to have to go down there and bail out your basement every year and try to repair that damage, and have some resilience against the way that it eats your house, the foundation of your house. And so then, what we do consequently with memories and with, just, love thoughts, really, is we store them in a place. And sometimes we pull ‘em out to tend to ‘em, you know.

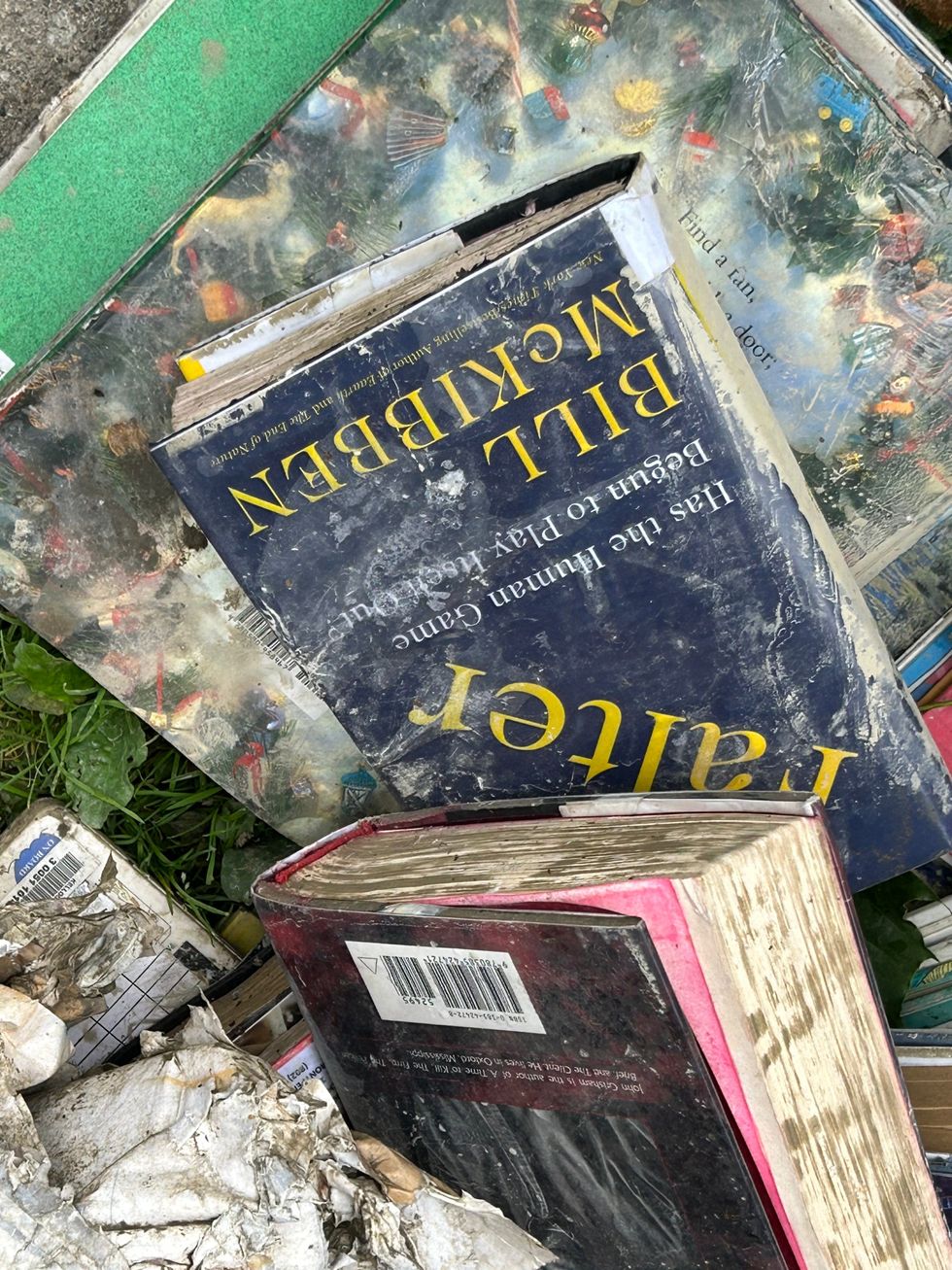

When I talked with her this week, she said—kindly—”I’m of course thinking about Vermont when I see stories like that,” and indeed we are busy across the Green Mountain State mucking out basements. Someone just sent me this picture of a book of mine about the climate crisis wrecked by the flooding and discarded in a pile outside the Montpelier library.

But of course in Detroit, and in so many other places, the devastation is compounded by specific histories of unfairness. As she wrote me the other day: “Divestment, decades of neoliberal policy—Detroit became the hole in the donut, surrounded by segregated, sometimes but not always wealthy, hostile suburbs. Water was central to the struggle between the city of Detroit, which has rights to some of the best drinking water in the country, and the suburbs, who have tried relentlessly to get it for pennies. A part of the Flint crisis was (then-governor) Snyder trying to avoid paying for Detroit Water.”

We’re used to the idea—adopted as a slogan in the Indigenous-led fight to block the Dakota Access pipeline—that “Mni Winconi—Water is Life.” And it is, of course. But it’s also sometimes other things. We’ve seen videos these past weeks of fast-rushing water devastating cities in Asia and Europe, with cars being swept down roads past buildings and hotels falling into rivers. Sea water off the Florida Keys set a new high-temperature record—101°F, or ‘hot tub’—and is in the process of devastating the coral reefs. Changes in salinity and temperature of that seawater are also threatening to collapse the Gulf Stream. And in places like Detroit, still water, in a rainy spring, can invade a basement, wrecking memories.

So much of what’s important about Detroit is the Blackness of it. You know, and as we lose that, just how much gets buried, whether it’s when freeways are created or when we just necessarily have to move forward, and things just get stored away. Maybe to be looked at some other time, but it could also be that they just end up being eaten up by the water, by the mold, by the neglect. I don’t have anything profound to say about erasure. It’s just this sinking feeling of, like, cities that may or may not have existed, you know, whether it was Atlantis or some city of gold. Will we exist moving forward? And if not, will these memories and these stories persist in 1,000 years?

We’re adults. We need room for fear and anger, and for planning and doing, but we also need room for reflection and melancholy. This film let me find that, and i hope it will do the same for you.