This newsletter is usually occupied with the action on the important fronts on the climate fight: what activists are doing, and oil companies, and banks, and governments, and so forth. It’s all crucial for one overriding reason: There’s a deadly-earnest race on to see if we can build renewable energy and conserve energy use generally before the ongoing heating overwhelms the physical systems of the planet. On any given day, worrying about exactly where we stand in that race is counterproductive; my job, anyway, is not to assess how hopeful I’m feeling at the moment. It’s to give hell to the bad guys and help to the good ones.

But we do occasionally need to take a step back and see how the fight is going, in part to satisfy our natural curiosity, and in part so we can know where best to press. Maybe it’s like reading polls in election season: helpful every once in a while, debilitating if done constantly. So here’s my best effort at a state-of-the-climate report as of early spring in the northern hemisphere 2024.

My reading of all these numbers is that the story remains largely the same, just more desperate.

At the most fundamental level, new figures last week showed that atmospheric levels of the three main greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—reached new all-time highs last year. Here’s how the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported the figures:

While the rise in the three heat-trapping gases recorded in the air samples collected by NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML) in 2023 was not quite as high as the record jumps observed in recent years, they were in line with the steep increases observed during the past decade.

The global surface concentration of C02, averaged across all 12 months of 2023, was 419.3 parts per million (ppm), an increase of 2.8 ppm during the year. This was the 12th consecutive year CO2 increased by more than 2 ppm, extending the highest sustained rate of CO2 increases during the 65-year monitoring record. Three consecutive years of CO2 growth of 2 ppm or more had not been seen in NOAA’s monitoring records prior to 2014. Atmospheric CO2 is now more than 50% higher than pre-industrial levels.

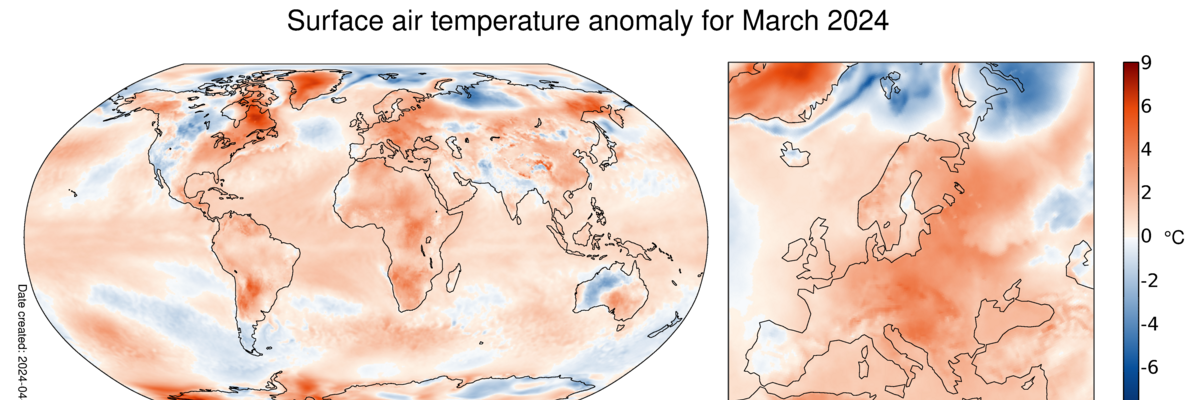

Entirely unsurprisingly, the planet’s temperature has also continued to rise. Temperature rise is not as smooth as the growth in greenhouse gas emissions, because other factors—El Niños, volcanoes, and so on—can superimpose themselves on top of the greenhouse gas emissions to push temperatures slightly higher or lower. But at the moment, everything is coming up very very hot. March was the hottest March ever recorded globally, according to European monitors. As The Guardian reported:

This is the 10th consecutive monthly record in a warming phase that has shattered all previous records. Over the past 12 months, average global temperatures have been 1.58°C above pre-industrial levels.

This, at least temporarily, exceeds the 1.5°C benchmark set as a target in the Paris climate agreement but that landmark deal will not be considered breached unless this trend continues on a decadal scale.

This is a very remarkable run of hot months. Some of it is no doubt due to El Niño, which is now beginning to conclude, but a variety of other factors—including, ironically, the phaseout of highly polluting bunker fuels to power large ships—may be involved as well. But none of these factors, even taken together, fully explain the jump, and so some scientists worry that we may have passed some physical landmark that sets the world’s climate in a new and not-well-understood state. Here’s Gavin Schmidt, who succeeded James Hansen in the critical role at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, writing in Nature:

It’s humbling, and a bit worrying, to admit that no year has confounded climate scientists’ predictive capabilities more than 2023 has.

Here’s part of the last paragraph of his analysis:

In general, the 2023 temperature anomaly has come out of the blue, revealing an unprecedented knowledge gap perhaps for the first time since about 40 years ago, when satellite data began offering modellers an unparalleled, real-time view of Earth’s climate system. If the anomaly does not stabilize by August—a reasonable expectation based on previous El Niño events—then the world will be in uncharted territory. It could imply that a warming planet is already fundamentally altering how the climate system operates, much sooner than scientists had anticipated.

Meanwhile, his predecessor Hansen has made his call:

Global warming in 2010-2023 is 0.30°C/decade, 67% faster than 0.18°C/decade in 1970-2010. The recent warming is different, peaking at 30-60°N; for clarity we show the zonal-mean temperature trend both linear in latitude and area-weighted. Such an acceleration of warming does not simply “happen”—it implies an increased climate forcing (imposed change of Earth’s energy balance). Greenhouse gas (GHG) forcing growth has been steady. Solar irradiance has zero trend on decadal time scales. Forcing by volcanic eruptions has been negligible for 30 years, including water vapor from the Honga Tunga eruption. The one potentially significant change of climate forcing is change of human-made aerosols. The large warming over the North Pacific and North Atlantic coincides with regions where ship emissions dominate sulfate aerosol production.

Warming is accelerating in the past 10-15 years, especially at midlatitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.

Fossil fuel use—the largest source by far of those emissions now heating the Earth so rapidly—is still going up. Earlier this week the International Energy Agency slightly raised its estimate of how much oil the planet would burn this year:

The EIA lifted total world-consumption forecasts for 2024 by 0.5% to 102.91 million bpd, and by 0.4% to 104.26 million bpd for 2025. Global oil production, meanwhile, was raised by 0.5% to 102.65 million bpd for 2024, and by 0.4% to 104.61 million bpd for 2025.

The rise is very small—essentially we’ve begun to plateau our fossil fuel use. That’s because large amounts of renewable energy are now coming online. Eighty-six percent of new capacity for power generation in 2023 was from renewables, with 473 gigawatts coming on line. That’s better than a gigawatt a day, something like the equivalent of a nuclear power plant.

But the crucial thing, of course, is not the total amount of renewables. It’s whether this is fast enough to meet the pace that scientists have told us is necessary to stop slowing down that heating—to cause the plateau in fossil fuel use to turn into a steep dive. And there we’re not going fast enough. The most important statistic in this newsletter—because it’s comparative—may come from a Paris-based think tank. The new report from Ren21 takes that 473 gigawatt figure and puts it up against what science requires. Here’s the bottom line, as Reuters reported it:

But it fell far short of the 1,000 GW per year required to meet the world’s climate commitments.

In other words, we’re going at less than half the pace we need to be going. And the growth in renewables is not evenly spread—outside of China, the developing world is getting a far-too-small share of this growth, lacking the investment necessary to drive rapid change.

The list of political players blocking change is relatively small. A new report this week found:

Over 70% of global CO2 emissions historically can be attributed to just 78 corporate and state producing entities.

But though small in number they are large in power.

My reading of all these numbers is that the story remains largely the same, just more desperate.

We have one force large enough to present any challenge to the rising temperature of the planet, and that is the rise of cheap renewable energy. But it’s not happening fast enough, and to speed it up requires political mobilization to break the power of the fossil fuel industry.

That’s why we do what do here at the Crucial Years, and why I spend my time volunteering at Third Act and elsewhere to make change. Thank you for being a part of that. Don’t let yourself be overwhelmed with either optimism or pessimism. Keep fighting.