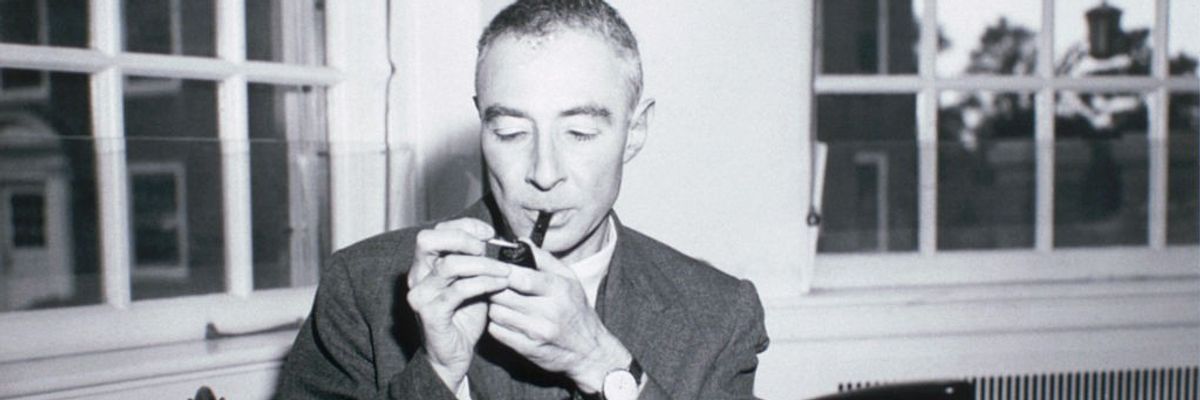

After seeing the movie Oppenheimer, a friend glumly commented, “I certainly don’t like them [nuclear weapons], but what can we do? We can’t put that genie back in its bottle.”

Those of us eager to get rid of nukes hear this a lot and at first glance it seems true; common sense suggests that we’re stuck with J. Robert Oppenheimer’s genie because after all, it can’t be disinvented. But this “common sense” is uncommonly wrong. Technologies have appeared throughout human history, and just as the great majority of plant and animal species have eventually gone extinct, ditto for the great majority of technological genies. Only rarely have they been actively erased. Nearly always they’ve simply been abandoned once people recognized they were inefficient, unsafe, outmoded, or sometimes just plain silly.

Don’t be bamboozled, therefore, by the oft-repeated claim by defense intellectuals that we can’t put the nuclear genie back in its bottle. We don’t have to. Plenty of lousy technologies have simply been forsaken. It’s their usual fate. (Dear readers, please don’t misunderstand. Our argument is NOT that nuclear weapons shouldn’t be actively restricted and eventually abolished. They should. Indeed, doing so is a major goal for basic planetary hygiene. Our point is that we, as a society and as antinuclear activists, shouldn’t be buffaloed by the widespread, influential claim that we are stuck with nukes simply because “that genie is out of the bottle.” Our argument isn’t, in itself, a profound case against nuclear weapons; we have made that point in other contexts, and we intend to keep doing so. Rather, we write to dispute one of the troublesome arguments that, for some people, has inhibited discussion about the necessity of nuclear abolition.)

Why isn’t it possible to imagine that they will be abandoned—just as other technologies that are dangerous and essentially useless?

Now, back to our thesis: that we’re not necessarily stuck with bad genies simply because they have somehow gotten out of their bottles. There are many instructive examples. The earliest high-wheel bicycles, called penny-farthings in England because their huge front wheel and tiny rear one resembled a penny alongside a farthing, were very popular in the 1870s and 1880s. They were not only difficult to ride, but dangerous to fall off.

Between 1897 and 1927, the Stanley Motor Carriage Company sold more than ten thousand Stanley Steamers, automobiles powered by steam engines. Both technologies are now comical curiosities, reserved for museums. Perhaps transportation intellectuals warned at the time that you couldn’t put the Stanley Steamer or penny-farthing genies back in their bottles.

Technological determinism—the idea that some objective technological reality decides what technologies exist—seems persuasive. After all, we can’t disinvent anything, nuclear weapons no less than penny-farthings and Stanley Steamers. There are no disinvention laboratories that undo things that shouldn’t have been done in the first place. To say that nuclear weapons will always be with us because they can’t be disinvented is like saying you will always be alive because you can’t be disborn.

Pessimists clinging to the myth of disinvention also argue that nuclear weapons can never be done away with because the knowledge of how to build them will always exist. Inventing something is conceived as a one-way process in which the crucial step is the moment of invention. Once that line has been crossed, there is no going back.

Again, this is superficially plausible. After all, it’s almost always the case that once knowledge is created or ideas are promulgated, they rarely go away. But there is a crucial difference between knowledge and ideas on the one hand, and technology on the other. Human beings don’t keep technology around (except sometimes in museums) the way they keep knowledge around in libraries, textbooks, and cultural traditions.

Bad ideas may persist in libraries, but not in the real world. The physicist Edward Teller, “father of the hydrogen bomb,” had some bad ideas. He urged, for instance, that H-bombs be used to melt arctic ice in order to dig seaports and also to free up the Northwest Passage, while other physicists, including Freeman Dyson, spent years on Project Orion, hoping to design a rocket that would be powered by a successive series of nuclear explosions. Crappy ideas don’t have to be forgotten in order to be abandoned.

Useless, dangerous, or outmoded technology needn’t be forced out of existence. Once a thing is no longer useful, it unceremoniously and deservedly gets ignored.

To understand how nuclear weapons might fit this mold, and be eliminated, look at technologies more generally, and how they go away. Venture capitalists, for example, are aware that new things don’t become permanent the moment they’re invented, nor do they disappear because they’ve been disinvented. Technologies have a life cycle whose two end points aren’t birth and death, but invention, then (sometimes) adoption, followed by either modification and continuation, or abandonment.

A new device can be utterly brilliant, but if it isn’t widely used, it won’t persist; certainly, it won’t live on forever just because it has been invented. Technologies go away when enough people decide to give up on them. This applies to weapons, too. Stone axes didn’t disappear because people couldn’t make them anymore, or because our ancestors ran out of stone. Iron replaced bronze, steel replaced iron. Spears, blowguns, bows and arrows, matchlock rifles, blunderbusses, the gatling gun: Each went extinct because they were simply abandoned, and for good reasons.

Consider the hand mortar. Developed in the 1600s, these guns (sort of like a sawed off, wide-barreled shotgun) were supposed to fire an exploding grenade at an adversary. At the time, however, triggers that could ignite on impact had not yet been developed, so the hand mortar relied on a somewhat complicated process: You primed the gun, set it down, grabbed the grenade (carefully!), lit its fuse, stuffed it in the gun’s muzzle, and shoved it all the way down the barrel, picked up the gun, aimed, and fired.

In theory, hand mortars ought to have been effective weapons. But there were lots of things that could go wrong, and did. The fuse could touch the grenade and detonate it in the barrel. Or the fuse could get doubled on itself as it was stuffed down the barrel, shortening the burn time, again detonating it in the barrel. The gun could misfire, leaving the grenade in the barrel, where it would eventually detonate. (None of these events were healthy for the soldier firing it.) The shock of shooting it could separate the fuse from the grenade, making it no more deadly than a thrown rock. If you mis-estimated the amount of powder needed to fire the grenade out of the gun incorrectly, it could either deposit the grenade at your feet or just a few yards away among your own troops, or it could send it sailing far over the heads of your adversaries.

As a practical matter, there were too many things that could go dangerously wrong with hand mortars, such that ultimately killing a knot of enemy soldiers if everything went right wasn’t worth the many risks involved. Even though hand mortars had been invented, and even though any madman who wanted to could have armed his forces with them, they had a negligible impact on war fighting. They were never outlawed or disinvented. Being a technology that was both dangerous and not very useful, they were simply abandoned.

And nuclear weapons? They are certainly dangerous, given that deterrence cannot persist indefinitely without someday failing. Bertrand Russell noted that one can imagine watching a tightrope walker balance aloft for five minutes, or even 15, but for a whole year? Or a hundred? At the same time, nuclear weapons have never been very useful, if indeed they have been useful at all, except to benefit those relatively few individuals, civilian and military, whose careers have profited from designing, developing, and deploying them.

So why isn’t it possible to imagine that they will be abandoned—just as other technologies that are dangerous and essentially useless? They could readily go extinct even though the memory of how to make them persists.

Yes, nuclear weapons cannot be disinvented. Oppenheimer and his colleagues bequeathed us something that was remarkable, not very useful, and very dangerous. The way to eliminate the danger is to understand that they were never a very good technology to begin with. And to recognize that insofar as they are bad genies they needn’t be stuffed back into their bottles. They can be left to fall of their own weight, or, alternatively, to suffer the fate suggested by Brent Scowcroft—no peacenik—when, in retirement, he was asked what should best be done with them: “Let ‘em rot.”