What’s in your basement? Mine is full of things I’ve mostly forgotten about—tools I bought for projects I never completed, long abandoned sports equipment, furniture I planned on refinishing ages ago, and unused cans of paint I thought I wanted when someone was giving them away.

We’ve owned this house for nearly 12 years, since just weeks before our son was born. In all that time, I’ve regularly gone down there to do the laundry and store my things (which never seem to stop accumulating). And somehow, it went from being empty when we bought it to chock-a-block full today in a way that would make Marie Kondo’s perfect hair stand straight up.

One day recently, I noticed two booklets attached by a screw with an outdated head to one of the beams under the basement stairs. That roused my curiosity since I had no memory of putting them there and, without laundry to distract me, I tried to free them, using a dozen different screwdrivers, none of which had that old-fashioned head, so eventually I pulled them loose with the claw end of a hammer.

Keep Calm and Head West

The top one was entitled “Emergency Planning at Connecticut’s Nuclear Power Plants: A Guidebook for Our Neighbors” and was addressed to “Resident.” Nowhere in that 23-page booklet was there a date, but it referred to our power company as Connecticut Light and Power and mentioned Connecticut Yankee, a local nuclear power plant that closed nearly 30 years ago.

We still get a similar booklet every couple of years, because we live seven miles from the area’s remaining nuclear power plant, all too aptly named Millstone and situated on a picturesque peninsula that juts into Long Island Sound. I sat in my kitchen, holding that ancient booklet and listening to the hum of the refrigerator (powered by—yes!—nuclear energy). The current PR line on nuclear power is that it’s a cheap and reliable bridge to renewable energy and a crucial partner in generating a carbon-free future. Here in Connecticut, half of all our power comes from Millstone, which is managed by Dominion Energy.

On its peninsula between Pleasure Beach and Hole in the Wall Beach, Millstone draws 2.2 billion gallons of water from Long Island Sound daily to use in its cooling towers. That water, according to a report from the Yale School of Management, is then returned to the Sound 32°F warmer than when it was pulled out. Scientists are now studying warm water plumes from Millstone, Indian Point, and other East Coast nuclear power plants to try to understand their impact on oxygen and nutrient levels in those waters. The Yale report notes that “populations of several commercially important species, including lobster and winter flounder, have steeply declined in Long Island Sound over the past two decades, but scientists are unsure whether overfishing, habitat degradation, disease, or warm water discharge from Millstone is to blame.”

As someone whose parents were well-known anti-nuclear activists and who’s always feared the possibility of a future nuclear war, I found myself riveted to the spot in the basement of my 1905 home, imagining my family of five seeking shelter here during some kind of nuclear catastrophe.

Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant, just about 80 miles due north of Baltimore, my childhood home, suffered a meltdown three days before my fifth birthday. So, I have a visceral fear of cooling towers and nuclear radiation. The booklet I found didn’t exactly allay my anxieties. It suggested that, in the event of a crisis at the plant, we should evacuate along a series of two-lane roads that have only gotten more congested in the decades since that booklet was published. “If possible, use only one car. If you have room, please check to see if any of your neighbors need a ride. Keep your car windows and air vents closed.” It suggested packing for a three-day trip and included a helpful list of things not to forget like pillows and toiletries. The booklet advised calm again and again, offering these (cold) comforting words, “Contrary to some popular misconceptions, a nuclear plant emergency would not be a sudden event. A severe nuclear accident would take considerable time to develop, enabling state and local officials to take the necessary protective actions in a timely fashion.” Tell that to the people of Chernobyl and Fukushima. How much time is time enough?

Build a Bunker, Survive the Fallout (But Not the Blast)

The second booklet was emblazoned with the all-caps title “FALLOUT PROTECTION FOR HOMES WITH BASEMENT” and was sent to our address in May 1967 by the Department of Defense’s Office of Civil Defense with the descriptor “Family Residing At.” As I leafed through the 60-year-old pages, I realized that the long-time homeowner had screwed it to the underside of the basement stairs in response to a suggestion on the back of the booklet: “For quick reference, hang this booklet in the corner of your basement having the best fallout protection.”

The booklet was personalized for our very basement based on a questionnaire the homeowner must have filled out once upon a time, because we were instructed to follow plans C through F to increase our “Protection Factor,” or PF, from radiation by 40%. Any “Home Handy Man,” we were assured, could construct a permanent shelter in the basement or at least pre-plan one to be quickly constructed after a nuclear attack. The booklet also had recommendations for how to improvise a shelter once you were cowering in that post-nuclear basement of yours. It did warn, however, that even if you had indeed constructed one, a “fallout shelter provides only limited protection against blast.”

There was, as it happened, no third booklet offering instruction to the home handyman on just how to protect his family from a future neighborhood nuclear blast and, of course, all these years later, there’s no fallout shelter in our basement and no stack of materials to make one with. Still, as someone whose parents were well-known anti-nuclear activists and who’s always feared the possibility of a future nuclear war, I found myself riveted to the spot in the basement of my 1905 home, imagining my family of five seeking shelter here during some kind of nuclear catastrophe. The walls are stones cobbled together with mortar and painted. That painted mortar regularly flakes onto the cement floor, coating it in a sort of crumbly dry snow. We occasionally squirt expanding foam into the holes in the foundation, but there’s still one corner where my kids like to hold their hands and exclaim: “I can feel the breeze” and “it smells like mud right here.” According to our Fallout Protection booklet, that corner is the “strongest” one, so before a nuclear attack, I do hope that I’ll get around to closing up all those holes.

Nuclear war is a constant hum in the back of my mind.

In truth, it would be a mighty grim existence in that basement of ours. Especially if I don’t fix the corner where the kids feel the breeze. There are lots of bikes, a massive canoe and life preservers, plenty of canning supplies, a dehydrator, heat lamps and other accessories for raising chickens, and my husband’s beer-making and distilling supplies. Most of these cool homesteadish things are useless without electricity, heat, or potable water.

The booklet offers no advice on how to supply a fallout shelter with water or beer or anything else, nor does it tell us how long we’d need to be down there. It does say: “Until the extent of the radiation threat in your town is determined by trained monitors using special instruments, you should stay in your shelter as much as possible. For essential needs, you can leave your shelter for a few minutes.” It suggests we get a battery-powered radio.

Of course, the information in that booklet is now 57 years old, long before the world of modern media arrived. I could go online and stream untold numbers of DIY tutorials on bunker-building and provisioning. By now, prepping for disasters, whether nuclear, conventional, or farcical is a multibillion-dollar business. You can even attend a weekend course on wilderness survival techniques for $800. However, nothing I read about that class offered guidance on surviving “a war, societal collapse, or some other calamity” with three kids, so I’m probably staying put. A battery-operated radio might not be a bad idea, though.

You Can’t Hide from Nukes

I mostly head down to the basement in a “keep the laundry-train running” fog. Nuclear war is a constant hum in the back of my mind. It’s a fear that won’t go away and that sets me apart from most Americans. It seems as if most of us deal with nuclear issues by—should the thought even occur to us—trying to push them away as quickly as possible. In an annual survey, Chapman University has been tracking American fears for nearly a decade now. Government corruption and economic collapse top the list, which also includes loved ones getting sick and dying. Fears of war are similarly prevalent, but the specific fear that stalks my dreams isn’t there—the possibility that the nightmare that rained down on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, killing more than 100,000 of them, when the United States became the first and only nation to use nuclear weapons, could happen again.

I know I’m an odd duck with my nuclear preoccupation. Of course, I live in the self-declared “Submarine Capital of the World.” New London/Groton has been building nuclear submarines since the 1950s, and the U.S. naval base here is home port to 15 nuclear attack submarines. So that’s one reason nukes are on my mind.

Then there are those two terrible wars raging right now between nuclear-armed invaders (Russia and

Israel) and non-nuclear entities (Ukraine and Hamas). Those nuclear-tinged wars worry me. And am I the only person who noticed that, just recently, the

Bulletin of Atomic Scientists decided to keep its Doomsday Clock at

90 seconds (yes, 90 seconds!) to midnight? I also read enough to know that our government is

going to spend more than $55 billion on nuclear weapons research, development, and testing in 2024 alone. And that figure doesn’t even include the whopping sums being invested in new nuclear delivery systems like

Columbia class submarines or the upgrading of the

B2 Spirit Stealth Bomber. I can get stuck there sometimes, especially when schools, clinics, and homeless shelters around me are struggling to keep their doors open.

Watching the (Nuclear) Clock at Family Gatherings

Such facts swirl in my head all the time—sometimes emitting a low hum, sometimes growing uncomfortably shrill. But I work hard to have other interests and worries. My anti-nuclear activist mother was constitutionally unable not to talk about nuclear weapons and that’s a cautionary tale for me. I can still remember how we wouldn’t go to family weddings or reunions or anything else scheduled in the first 10 days of August, because we were memorializing the bombings of Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945). Since my mother was one of seven siblings in a big Irish Catholic family and had dozens of nieces and nephews, we missed a lot of family summer gatherings thanks to that principle.

Perhaps it was for the best, though, since I do remember one truly awkward exchange between my mother and a relative:

“Oh hi, Liz, good to see you. You look lovely. How have you been?”

And my mom replied: “Well, I’ve been better. We’re three minutes to nuclear midnight, you know. It keeps us very busy.” (In those days, the Bulletin’s Doomsday Clock was slightly farther from “midnight.”)

An uncomfortable silence followed, spreading like nuclear winter and eventually the relative excused herself to get another martini.

Now that I think about it, the best protection to be found in that basement of mine is our stash of anti-nuclear protest signs.

I try not to do that myself to unsuspecting friends and relatives, but I’d be lying if I told you that sometimes I didn’t think like my mom.

Unlike me, most people have, I suspect, stuck the whole history, science, and politics of that world-killing technology in the proverbial basement (though not ours, of course). So, imagine my surprise when I found all that strange history stuck in my own basement!

The Only Protection is Prohibition

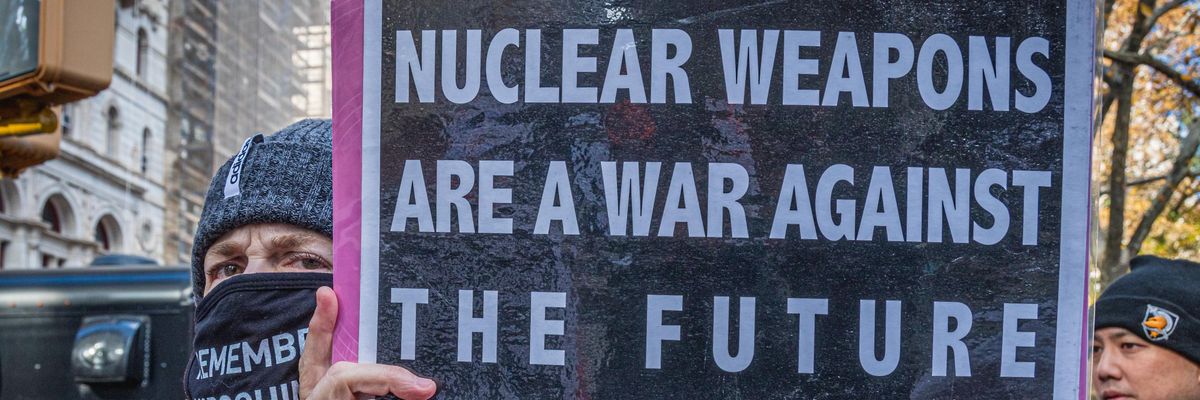

Now that I think about it, the best protection to be found in that basement of mine is our stash of anti-nuclear protest signs. In one corner are all the ones the Connecticut Committee to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons uses in its protests. There are “disarm now” signs, a sturdy yellow banner with quotes from the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and a stack of 70 “Thank You” posters for each of the nations that are party to that Treaty. My kids, some of our friends, and I made those signs to express our gratitude to countries like Benin, Honduras, and Thailand that have agreed (unlike the nine countries with such weaponry) not to develop, test, produce, manufacture, acquire, or possess, no less stockpile nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices, or accept nuclear weapons from other countries, or allow them to be stored on their territory.

Mark Twain supposedly said that war is how Americans learn geography. In making those signs and waving them near the local General Dynamics complex contracted to design the next generation of nuclear-capable submarines, my kids and I are learning a different kind of geography. As we resist, we celebrate the geography of the true superpowers on this planet, the nations that are trying to lead the way to a nuclear-free, bunker-free future where children won’t have to even imagine hiding in their basements.

In the meantime, I’m going to hang these two booklets back up under the basement stairs as relics of what I’d love to think of as a bygone era. I just have to find the right screwdriver.