Since the first reviews of the Oppenheimer film appeared, a question has been floating in the ether: Why don’t we see substantial images of the destruction and victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-Bombs?

Days before the Academy Awards, I had the opportunity to learn the answers to that question. I had just returned from Japan, where I marched with Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors (Hibakusha) and participated in 70th anniversary commemorations of the victims of the Bikini Bravo H-Bomb test on March 1, 1954. That bomb was 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on the people of Hiroshima. It claimed and poisoned the lives of nearly all the inhabitants of Rongelap atoll 125 miles away from Bikini. It also claimed the lives of Japanese fishermen and irradiated more than 1,000 Japanese fishing vessels and contaminated much of Japan’s food supply. The resulting 1954-55 petition campaign urging the abolition of nuclear weapons garnered 31.5 million petition signatures, 65% of Japanese voters, and launched the world’s first and likely most influential social movement for a nuclear weapons-free world.

I was carrying these people and this history deep in my bones when Harvard Professor Elaine Scarry, a friend and member of my organization’s board, encouraged me to come to a panel she had organized with Kai Bird, co-author of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of Robert J. Oppenheimer, the biography on which the Oppenheimer film is based.

I have known Kai and his now late co-author Martin Sherwin, over the years. Kai is a generous and modest man, and an excellent scholar and biographer. We chatted briefly before the panel, where I learned and was happy for him that he will be at the Academy Awards for the Oscars tonight.

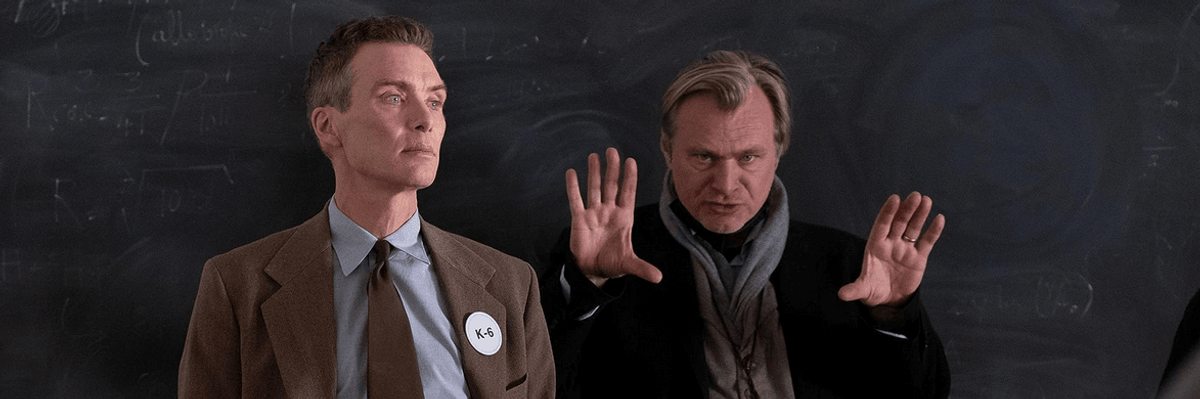

In his presentation, Kai explained that the film drew heavily from his book, with many of its lines taken directly from his and Marty’s text—something very unusual for Hollywood. Kai was given only a few hours to review the film’s 200-page script before the filming began, and he said that he found only one error, which Christopher Nolan, the film's director, corrected. Kai and the other panelist, Peter Galison of Harvard’s History of Science Department, described Oppenheimer as brilliant (physicist and otherwise), complex, and emotionally fragile, a man who might have been better known for his work on black holes—begun in 1935—had World War II and the Manhattan Project not intervened.

Come the question and answer time, after a brief reference to what I had learned and did in Japan, I asked Kai if Nolan, during production of the film, had any serious conversations about exposing his audiences to what Oppenheimer’s bomb wrought? Kai’s answer was thoughtful and illuminated some of the most disturbing images from the film’s conclusion.

Kai’s direct response was “No.” Such discussions did not take place, Kai had earlier explained that the dramatic arc of the film and the book were the Atomic Energy Commission hearings in which those in power sought to destroy Oppenheimer’s role as the world’s leading scientist and very influential public intellectual. Edward Teller, Lewis Strauss of the AEC, and powerful forces in the Pentagon reacted with fury to Oppie’s opposition to developing the hydrogen bomb. Kai explained that the film and book are primarily biographies of Oppenheimer with as Elaine put it, the film “telling the story from the point of view of what’s going on in Oppenheimer’s mind,” not from other and broader perspectives

Kai noted several places in the film where Nolan subtly pointed to both the A-bombs’ devastation and Oppenheimer’s moral misgivings. The first of the film’s references comes shortly after the Trinity test, with another three months after the A-bombings when Oppenheimer learned that Japan had been on the verge of surrender at the time his “gadgets” were fired. At one point, following the Trinity test we see Oppenheimer mumbling about those “poor little people,” the innocent Japanese civilians who he knew would be killed and devastated by the A-bombs. At the same time, Kai noted, Oppenheimer was meeting with senior military officials to explain how best to detonate the bombs (altitude, etc.)

Instead of showing us the roasted bodies, people with burnt flesh hanging from their arms, eyeballs hanging from their sockets, and people drowned in cisterns, Nolan gave us the image of Oppenheimer watching a newsreel clip of the devastation, with his face showing his horror at what his bomb had wrought. Perhaps most powerfully, we see a disturbing image from Oppenheimer’s imagination as he speaks to an audience in the Los Alamos assembly hall: a girl’s face melting from the A-bomb’s heat. That face, in fact, was that of Nolan’s daughter, as Elaine Scarry later explained. “This was a very ethical decision on Nolan’s part," she said, "not to reenact the original harm by disfiguring Japanese faces.”

And Nolan gives us Oppenheimer’s sense of guilt when he meets with President Truman and Secretary Byrnes, confronting them with the truth that they all have blood on their hands.

Elaine closed out this part of the panel discussion by pointing to the resistance in U.S. culture to seeing film scenes in which “the viewer is asked to be sympathetic to the person injured.” In Japan, she explained, even young children are shown horrific photos and images of the A-bomb’s human devastations. She reinforced this by explaining that she and I arranged an exhibit of framed Hiroshima/Nagasaki A-bomb and Hibakusha posters in a Cambridge public library. The morning after we set up the display we returned to the library to find that it had been totally rearranged without our permission or knowledge. Each of the posters that included photos of the dead and maimed had been removed.

After the panel, my wife and I resolved to watch the film again. Others who have already seen the film and watched the Academy Awards and who shared my question might also want to do the same. If nothing else, it will deepen our resolve to eliminate the existential nuclear threat to human survival.