SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

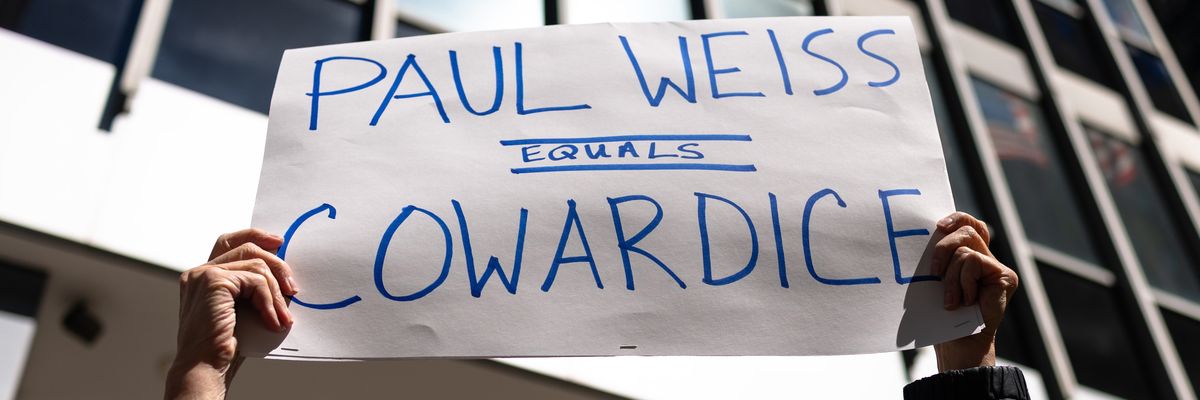

people hold signs as they protest outside of the offices of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison LLP on March 25, 2025 in New York City.

The decision was a culminating event in Big Law’s transformation from a noble profession to a collection of profit-maximizing businesses.

1,613.

That’s how many words Brad Karp, chairman of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison LLP, used in his March 23 memo defending his firm’s capitulation to U.S. President Donald Trump.

One would have been enough: greed.

Observers have been shocked and puzzled at Paul Weiss’ refusal to fight Trump’s unconstitutional order aimed at destroying the firm. But its decision was a culminating event in Big Law’s transformation from a noble profession to a collection of profit-maximizing businesses.

The Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law.

The Lawyer Bubble: a Profession in Crisis documents that transformation. It’s based on my 30-year career as a litigator in Big Law—a select group of the nation’s largest and most lucrative law firms. The vast majority share the same goal: maximizing equity partners’ current income. A few metrics—size, growth, revenues, billable hours, leverage, profits per partner—have become the definitive measures of a firm’s success.

By those criteria, Paul Weiss has been wildly successful. In 2024, the firm’s revenues exceeded $2.6 billion and its average profits per equity partner were more than $7.5 million.

Karp addressed his memo to the “Paul Weiss Community” of more than 1,000 lawyers. But the real players at any Big Law firm are the equity partners. As of September 2024, Paul Weiss had 212.

At most firms, a small subset of that group controls clients that bring in the most business. Those equity partners run the place, set the culture, and get the largest share of the profits pie. On average, the highest-paid equity partners in a Big Law firm earn 10 times more than their lowest-paid equity-partner colleagues.

From an economic perspective, it’s important to run any large institution efficiently. But most Big Law firm leaders have become so obsessed with the metrics of their business model that they have forgotten why they went to law school in the first place.

Practicing law is not just maximizing revenues and minimizing costs. But the Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law. Karp’s memo observes that, like many Big Law firms, Paul Weiss attorneys donate significant time to worthy causes. That’s laudable but no excuse for caving in to Trump’s unlawful demands.

Trump’s relentless assault on the judicial system has targeted attorneys and judges as “unfair” to him personally. None of those specious attacks reached Big Law or its business model until now.

Trump directed his first Big Law assault at Covington & Burling, but it was limited to a handful of individuals. Then he went after everyone at Perkins Coie. With survival on the line, Perkins Coie and its litigation counsel Williams & Connolly rose to the challenge. Federal District Court Judge Beryl Howell sided with the firm and brought Trump’s effort to a screeching halt.

Except it didn’t. After that unambiguous loss, Trump issued a similar order against Paul Weiss. It was classic Trump: Never admit a mistake; after a defeat, double down. Trump then sought Judge Howell’s disqualification from the Perkins Coie case. He lost that one too.

Rarely does a potential litigant have the confidence of victory that Judge Howell’s ruling in favor of Perkins Coie had given Paul Weiss. For many reasons, resistance should have been an easy call.

First, every attorney’s sworn oath demanded it. Upon entering the bar, all lawyers pledge to defend the Constitution and uphold the rule of law. We don’t get to pick and choose when to honor it.

Second, Paul Weiss’s multimillionaire equity partners could afford the fight financially.

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

Third, along with the corporate world, the entire legal profession was looking to Paul Weiss—one of the most preeminent Big Law firms—for leadership at a dangerous moment.

Finally, Trump had declared that his attacks on the judiciary system, Big Law, and anyone he disfavored would continue.

But Paul Weiss capitulated. Karp said that clients worried about retaining a law firm that was “persona non grata” with the administration—a phrase he used twice in his memo. If that’s true, those clients are as short-sighted as Karp and his colleagues. Whether a client thinks its lawyer should resist a rogue president is irrelevant.

Perhaps the firm did not explain to its corporate clients the long-run implications of capitulation. Without the rule of law, the underlying legal certainty necessary for effective commerce disappears. Contracts become unenforceable. Constitutional rights are lost. Chaos reigns.

Even at a practical level, relying on attorneys who give in to Trump’s unlawful demands is risky. What happens when those clients become persona non grata because Trump directs his next arbitrary and illegal attack at them? How will clients feel when the only lawyers who are not persona non grata are the ones whom Trump likes? Should clients worry that its lawyers’ desire to remain “Trump-approved” might tempt their counsel to compromise clients’ interests when challenging his administration’s illegal policies?

Karp also said that he followed the path that the firm recommends to clients facing “bet-the-company” litigation: settle rather than risk extinction. Let’s test that with a thought experiment:

A client comes to Paul Weiss with a “bet-the-company” crisis. Precedent in an identical case virtually guarantees that the client will win.

“If you settle this frivolous attack, it will embolden your adversaries,” the lawyer warns. “In the long-run, the best business decision is to fight it.”

“Is that what you would do?” the client asks.

“Yes,” the attorney responds.

“But it’s not what you did, is it?”

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

As William Bruce Cameron said, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

The fight isn’t over. Four days after Paul Weiss surrendered, Trump issued an executive order targeting Jenner & Block.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

1,613.

That’s how many words Brad Karp, chairman of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison LLP, used in his March 23 memo defending his firm’s capitulation to U.S. President Donald Trump.

One would have been enough: greed.

Observers have been shocked and puzzled at Paul Weiss’ refusal to fight Trump’s unconstitutional order aimed at destroying the firm. But its decision was a culminating event in Big Law’s transformation from a noble profession to a collection of profit-maximizing businesses.

The Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law.

The Lawyer Bubble: a Profession in Crisis documents that transformation. It’s based on my 30-year career as a litigator in Big Law—a select group of the nation’s largest and most lucrative law firms. The vast majority share the same goal: maximizing equity partners’ current income. A few metrics—size, growth, revenues, billable hours, leverage, profits per partner—have become the definitive measures of a firm’s success.

By those criteria, Paul Weiss has been wildly successful. In 2024, the firm’s revenues exceeded $2.6 billion and its average profits per equity partner were more than $7.5 million.

Karp addressed his memo to the “Paul Weiss Community” of more than 1,000 lawyers. But the real players at any Big Law firm are the equity partners. As of September 2024, Paul Weiss had 212.

At most firms, a small subset of that group controls clients that bring in the most business. Those equity partners run the place, set the culture, and get the largest share of the profits pie. On average, the highest-paid equity partners in a Big Law firm earn 10 times more than their lowest-paid equity-partner colleagues.

From an economic perspective, it’s important to run any large institution efficiently. But most Big Law firm leaders have become so obsessed with the metrics of their business model that they have forgotten why they went to law school in the first place.

Practicing law is not just maximizing revenues and minimizing costs. But the Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law. Karp’s memo observes that, like many Big Law firms, Paul Weiss attorneys donate significant time to worthy causes. That’s laudable but no excuse for caving in to Trump’s unlawful demands.

Trump’s relentless assault on the judicial system has targeted attorneys and judges as “unfair” to him personally. None of those specious attacks reached Big Law or its business model until now.

Trump directed his first Big Law assault at Covington & Burling, but it was limited to a handful of individuals. Then he went after everyone at Perkins Coie. With survival on the line, Perkins Coie and its litigation counsel Williams & Connolly rose to the challenge. Federal District Court Judge Beryl Howell sided with the firm and brought Trump’s effort to a screeching halt.

Except it didn’t. After that unambiguous loss, Trump issued a similar order against Paul Weiss. It was classic Trump: Never admit a mistake; after a defeat, double down. Trump then sought Judge Howell’s disqualification from the Perkins Coie case. He lost that one too.

Rarely does a potential litigant have the confidence of victory that Judge Howell’s ruling in favor of Perkins Coie had given Paul Weiss. For many reasons, resistance should have been an easy call.

First, every attorney’s sworn oath demanded it. Upon entering the bar, all lawyers pledge to defend the Constitution and uphold the rule of law. We don’t get to pick and choose when to honor it.

Second, Paul Weiss’s multimillionaire equity partners could afford the fight financially.

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

Third, along with the corporate world, the entire legal profession was looking to Paul Weiss—one of the most preeminent Big Law firms—for leadership at a dangerous moment.

Finally, Trump had declared that his attacks on the judiciary system, Big Law, and anyone he disfavored would continue.

But Paul Weiss capitulated. Karp said that clients worried about retaining a law firm that was “persona non grata” with the administration—a phrase he used twice in his memo. If that’s true, those clients are as short-sighted as Karp and his colleagues. Whether a client thinks its lawyer should resist a rogue president is irrelevant.

Perhaps the firm did not explain to its corporate clients the long-run implications of capitulation. Without the rule of law, the underlying legal certainty necessary for effective commerce disappears. Contracts become unenforceable. Constitutional rights are lost. Chaos reigns.

Even at a practical level, relying on attorneys who give in to Trump’s unlawful demands is risky. What happens when those clients become persona non grata because Trump directs his next arbitrary and illegal attack at them? How will clients feel when the only lawyers who are not persona non grata are the ones whom Trump likes? Should clients worry that its lawyers’ desire to remain “Trump-approved” might tempt their counsel to compromise clients’ interests when challenging his administration’s illegal policies?

Karp also said that he followed the path that the firm recommends to clients facing “bet-the-company” litigation: settle rather than risk extinction. Let’s test that with a thought experiment:

A client comes to Paul Weiss with a “bet-the-company” crisis. Precedent in an identical case virtually guarantees that the client will win.

“If you settle this frivolous attack, it will embolden your adversaries,” the lawyer warns. “In the long-run, the best business decision is to fight it.”

“Is that what you would do?” the client asks.

“Yes,” the attorney responds.

“But it’s not what you did, is it?”

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

As William Bruce Cameron said, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

The fight isn’t over. Four days after Paul Weiss surrendered, Trump issued an executive order targeting Jenner & Block.

1,613.

That’s how many words Brad Karp, chairman of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, & Garrison LLP, used in his March 23 memo defending his firm’s capitulation to U.S. President Donald Trump.

One would have been enough: greed.

Observers have been shocked and puzzled at Paul Weiss’ refusal to fight Trump’s unconstitutional order aimed at destroying the firm. But its decision was a culminating event in Big Law’s transformation from a noble profession to a collection of profit-maximizing businesses.

The Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law.

The Lawyer Bubble: a Profession in Crisis documents that transformation. It’s based on my 30-year career as a litigator in Big Law—a select group of the nation’s largest and most lucrative law firms. The vast majority share the same goal: maximizing equity partners’ current income. A few metrics—size, growth, revenues, billable hours, leverage, profits per partner—have become the definitive measures of a firm’s success.

By those criteria, Paul Weiss has been wildly successful. In 2024, the firm’s revenues exceeded $2.6 billion and its average profits per equity partner were more than $7.5 million.

Karp addressed his memo to the “Paul Weiss Community” of more than 1,000 lawyers. But the real players at any Big Law firm are the equity partners. As of September 2024, Paul Weiss had 212.

At most firms, a small subset of that group controls clients that bring in the most business. Those equity partners run the place, set the culture, and get the largest share of the profits pie. On average, the highest-paid equity partners in a Big Law firm earn 10 times more than their lowest-paid equity-partner colleagues.

From an economic perspective, it’s important to run any large institution efficiently. But most Big Law firm leaders have become so obsessed with the metrics of their business model that they have forgotten why they went to law school in the first place.

Practicing law is not just maximizing revenues and minimizing costs. But the Big Law business model values only what it can measure. And there’s no metric for defending the Constitution, preserving democracy, or upholding the rule of law. Karp’s memo observes that, like many Big Law firms, Paul Weiss attorneys donate significant time to worthy causes. That’s laudable but no excuse for caving in to Trump’s unlawful demands.

Trump’s relentless assault on the judicial system has targeted attorneys and judges as “unfair” to him personally. None of those specious attacks reached Big Law or its business model until now.

Trump directed his first Big Law assault at Covington & Burling, but it was limited to a handful of individuals. Then he went after everyone at Perkins Coie. With survival on the line, Perkins Coie and its litigation counsel Williams & Connolly rose to the challenge. Federal District Court Judge Beryl Howell sided with the firm and brought Trump’s effort to a screeching halt.

Except it didn’t. After that unambiguous loss, Trump issued a similar order against Paul Weiss. It was classic Trump: Never admit a mistake; after a defeat, double down. Trump then sought Judge Howell’s disqualification from the Perkins Coie case. He lost that one too.

Rarely does a potential litigant have the confidence of victory that Judge Howell’s ruling in favor of Perkins Coie had given Paul Weiss. For many reasons, resistance should have been an easy call.

First, every attorney’s sworn oath demanded it. Upon entering the bar, all lawyers pledge to defend the Constitution and uphold the rule of law. We don’t get to pick and choose when to honor it.

Second, Paul Weiss’s multimillionaire equity partners could afford the fight financially.

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

Third, along with the corporate world, the entire legal profession was looking to Paul Weiss—one of the most preeminent Big Law firms—for leadership at a dangerous moment.

Finally, Trump had declared that his attacks on the judiciary system, Big Law, and anyone he disfavored would continue.

But Paul Weiss capitulated. Karp said that clients worried about retaining a law firm that was “persona non grata” with the administration—a phrase he used twice in his memo. If that’s true, those clients are as short-sighted as Karp and his colleagues. Whether a client thinks its lawyer should resist a rogue president is irrelevant.

Perhaps the firm did not explain to its corporate clients the long-run implications of capitulation. Without the rule of law, the underlying legal certainty necessary for effective commerce disappears. Contracts become unenforceable. Constitutional rights are lost. Chaos reigns.

Even at a practical level, relying on attorneys who give in to Trump’s unlawful demands is risky. What happens when those clients become persona non grata because Trump directs his next arbitrary and illegal attack at them? How will clients feel when the only lawyers who are not persona non grata are the ones whom Trump likes? Should clients worry that its lawyers’ desire to remain “Trump-approved” might tempt their counsel to compromise clients’ interests when challenging his administration’s illegal policies?

Karp also said that he followed the path that the firm recommends to clients facing “bet-the-company” litigation: settle rather than risk extinction. Let’s test that with a thought experiment:

A client comes to Paul Weiss with a “bet-the-company” crisis. Precedent in an identical case virtually guarantees that the client will win.

“If you settle this frivolous attack, it will embolden your adversaries,” the lawyer warns. “In the long-run, the best business decision is to fight it.”

“Is that what you would do?” the client asks.

“Yes,” the attorney responds.

“But it’s not what you did, is it?”

As leaders of the profession in these perilous times, all Big Law partners have a special obligation to think beyond the metrics of profit-maximization.

As William Bruce Cameron said, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

The fight isn’t over. Four days after Paul Weiss surrendered, Trump issued an executive order targeting Jenner & Block.