There is a lot of talk from big oil companies about fossil gas being here to stay. Bloomberg recently reported that “(f)rom Shell Plc to Chevron Corp., the world’s top producers plan to accelerate investments in [gas].”

The companies are getting two things wrong about the outlook for fossil gas. First, they seem to think that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means that Europe and Asia are happy to continue to rely heavily on gas. The thinking seems to be that they need to source their supply from anywhere other than Russia and carry on as if nothing happened. They are ignoring the huge shift toward renewables and efficiency taking place as Russia’s actions clarify that a gas-reliant energy strategy will forever be vulnerable to geopolitics and price volatility. While China is signing some long-term liquified gas (LNG) contracts, it’s also accelerating its shift to renewables, just like Europe.

Their second mistake is pretending that finally tackling the profligate methane emissions caused by gas production will give them carte-blanche to produce as much fossil gas as possible. They are simply ignoring science.

For clarification, greenhouse gases are emitted all along the oil and gas lifecycle. Burning gas produces carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas causing the climate crisis. Additionally, methane, the primary component of fossil gas, is emitted directly into the atmosphere in the process of producing, processing, transporting, and storing oil and gas. Methane has a warming impact over 80 times greater than carbon dioxide in the short term. Reducing these methane emissions is crucial. So is phasing out fossil gas altogether.

It is abundantly clear that the production and consumption of fossil gas must decline immediately, even if methane reduction goals are met. No amount of wishful thinking about upstream emissions reduction, carbon capture and storage (CCS), gas-based “blue” hydrogen, or whatever the latest magical techno-fix the industry imagines will save it can change this fact. Indeed, when you look at how well methane emissions reduction and carbon capture are faring thus far, it is more than likely that gas will need to go into a steeper decline than most current models project.

Models show that fossil gas must be phased out

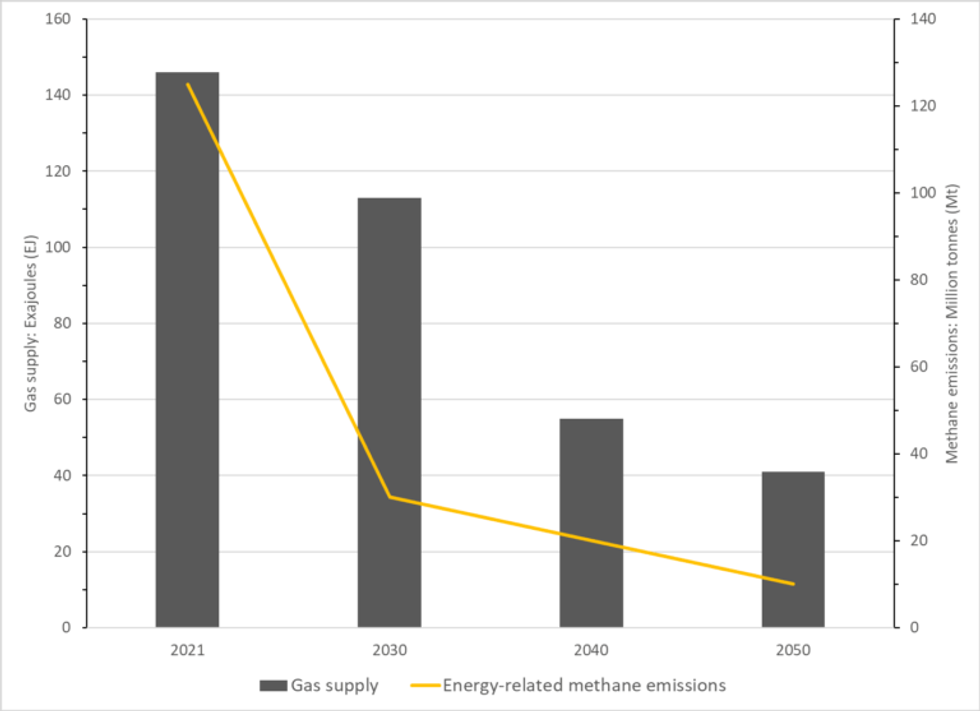

The clearest articulation comes in the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Net Zero Emissions (NZE) energy scenario updated in the 2022 World Energy Outlook. In this scenario, greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector are reduced in line with a roughly 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. The scenario has high ambitions for the industry’s favorite escape hatches, such as carbon capture, hydrogen, and upstream methane emissions reduction. But even if these technologies deliver the full potential that the scenario models, gas production is still projected to decline 22% by 2030 from 2021 levels. By 2050, gas production should be more than 70% lower than it is today. This of course assumes that the emissions from much of the remaining gas use are “abated” by CCS.

The trajectory of global energy-related methane emissions and global fossil gas production in the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions scenario is shown in the chart below.

Source: Oil Change International & Earthworks using data from IEA 2022 World Energy Outlook.

Source: Oil Change International & Earthworks using data from IEA 2022 World Energy Outlook.

The decline in energy-related methane emissions by 2030 projected in the scenario is very ambitious. It is a decline of more than 75% in a decade. By 2050, emissions are expected to be just 8% of 2021 levels. Achieving these reductions would be impactful. Methane is a climate super-pollutant that is thought to be responsible for around 30% of the global warming and related impacts, like mega wildfires, droughts, and hurricanes, being felt today. But keeping it from entering the atmosphere while producing oil, gas, and coal is difficult. If it weren’t, the industry would have made more progress than it has. After all, the methane that the industry spews into the atmosphere, both as part of routine operations and through faulty equipment and bad practice, is worth money. And we know that the number one thing that the oil and gas industry cares about is, well, money.

The industry is failing on methane

The progress so far doesn’t look encouraging. The IEA announced in February that “(m)ethane emissions remained stubbornly high in 2022 even as soaring energy prices made actions to reduce them cheaper than ever.” The agency’s Global Methane Tracker found that “the global energy industry was responsible for 135 million tonnes of methane released into the atmosphere in 2022, only slightly below the record highs seen in 2019.”

IEA Executive Director, Fatih Birol, warned the industry that there was “no excuse.” “Some progress is being made, but […] emissions are still far too high and not falling fast enough – especially as methane cuts are among the cheapest options to limit near-term global warming.” He also said that the “Nord Stream pipeline explosion last year released a huge amount of methane into the atmosphere. But normal oil and gas operations around the world release the same amount of methane as the Nord Stream explosion every single day.”

The numbers are stark. As the war in Ukraine raged, and global energy prices soared, the oil and gas industry raked in $4 trillion in profits. Birol further pointed out that less than 3% of these profits, roughly $100 billion, is what it would take to reduce energy-related methane emissions by 75% with existing technologies. Yet, the industry is focused on dividends, share buybacks, and reinvesting its cash haul into more oil and gas.

Time to get real

The industry’s methane reduction efforts not only need to gather pace. The industry also needs to be realistic about the role of methane reduction in climate mitigation. It’s not just the CEOs of big oil and gas companies that are getting this wrong. It’s also people like Project Canary CEO Chris Romer. Project Canary is one of the leading companies certifying methane emissions reduction in the United States.

In October 2022, Romer argued that “people need to understand that [U.S. methane gas] is the cleanest carbon on the planet, and we need to bring two billion people out of poverty with this enormously clean carbon fuel.” He adds, “We need to expand LNG globally by a big number. The U.S. is ready to do that in a very big way. We would love it to be certified gas. We would love it to be Project Canary-certified gas.”

In May, Oil Change International and Earthworks released a report about Project Canary and its deeply flawed certified gas operation. A significant part of our findings was about the failure of Canary’s technology to do what it claims to do and detect and help reduce methane emissions. Another piece was how Project Canary and its customers are attempting to mislead governments and gas markets about the role of methane reduction in climate mitigation.

What our report makes clear is that methane emissions reduction is only one part of what the oil and gas industry must do to prevent the current climate crisis from evolving into a full-blown planetary catastrophe. It is clearer than ever that the climate crisis requires a rapid and managed phase-out of fossil fuel production. Reducing the wasteful practice of emitting methane into the atmosphere does not give the gas industry a pass. They need to clean up and wind down. And they need to start now.

Source:

Source: