In March, the Big Three manufacturers of insulin, who control over 90% of the insulin market in the U.S., announced highly publicized list price cuts to some insulins, after decades of

unchecked price increases on the 100-year-old drug that costs $6 a vial to produce. In response, some claimed that California’s foray into the insulin market (by way of a contract with the nonprofit CivicaRx to produce the state’s own insulin) was no longer needed. But recent findings confirm what advocates have known for a long time: The system of fully private, profit-driven production is not working for patients.

Lilly’s insulin Lispro was supposed to be available for $25 as of May 1.

T1International recently shared that the average list price quoted to patient advocates attempting to acquire the $25 insulin since May 1 has been $107.31, while Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s (D-WMass.) office found chain stores charged uninsured customers an average of $123 per vial for the generic insulin, and nearly half (43%) of surveyed pharmacies did not stock it.

To create sustainable change in the insulin market and to truly lower costs to patients, we need to think outside of the dominant systems that rely on corporate actors to implement change—we need public pharma options.

Ultimately, insulin manufacturers and the pharmaceutical industry must be held accountable for putting profits over patients through legislation that permits price-lowering solutions to move quickly ahead.

“Public Pharma” refers to options in which state actors take or complement roles that private companies usually have in pharma: manufacturing, distributing, and pricing prescription drugs. Three variations of Public Pharma are: public manufacturing, in which the state manufactures the drug; public procurement, in which states purchase drugs in bulk quantities at a lower price and distribute them; and public PBMs, in which the state(s) negotiate lower prices for public or private entities to purchase.

States who invest in public manufacturing of insulin and other medicines are investing in the future of their citizens. The demand for insulin, which is as essential as water to a person with type 1 diabetes, will only increase in the coming years, with rates of diabetes in young U.S. populations predicted to

rise dramatically. The current faulty system has resulted in an estimated 1.3 million Americans rationing their insulin in the last year. States that provide affordable and accessible insulin will save money through fewer emergency room visits for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a consequence of rationing that costs an average of $30,000 per ER visit. They can also count on a reduction of long-term complications caused by the inability to correctly manage diabetes with insulin, such as amputations, kidney failure, vision damage, and more. In 2019, taxpayer-funded programs like Medicare and Medicaid spent over $120 billion (65% of total expenditures) on total health expenditures, including over $25 billion on insulin. If patients were able to buy their medicine at a price that is close to the manufacturing cost—or better yet, receive it for free—money would be saved and quality of life would be vastly improved.

Public manufacturing will also create new jobs and allow states to take ownership of the supply chain. There is opportunity to sell the publicly produced medicines to other states interested in contracting for lower cost options. And of course, states are not limited to only addressing insulin costs, but can focus on other high priced drugs in the future, as

California is doing with Naloxone.

Public Pharma initiatives, most specifically targeting insulin, have already been started in Washington,

Maine, Michigan, and California, with Michigan and California both budgeting significant funds for the efforts ($150 million and $100 million, respectively). Establishing a manufacturing facility and getting FDA approval is a longer process, so while public manufacturing should be the end goal among the various pathways, establishing interim solutions with public PBMs (as Washington, Oregon, Nevada, and Connecticut have done with ArrayRX) and public procurement options can lower prices quickly and save states money. Additionally, creating a public-private partnership by contracting with a nonprofit like Civica, as California has done for their state brand CalRx, could lower costs for some patients as soon as 2024, since they are further along in the drug development and approval process for insulin. Ultimately, insulin manufacturers and the pharmaceutical industry must be held accountable for putting profits over patients through legislation that permits these and other price-lowering solutions to move quickly ahead.

Public manufacturing has

already been implemented successfully by several states. Massachusetts and Michigan have both developed, manufactured, and marketed biologics (including vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and immunoglobulins) in the past, and Massachusetts continues to do so today through MassBiologics. The California Department of Public Health produces BabyBIG, a biologic drug used to treat infant botulism, which was developed and produced in response to a high incidence of infant botulism cases in the state.

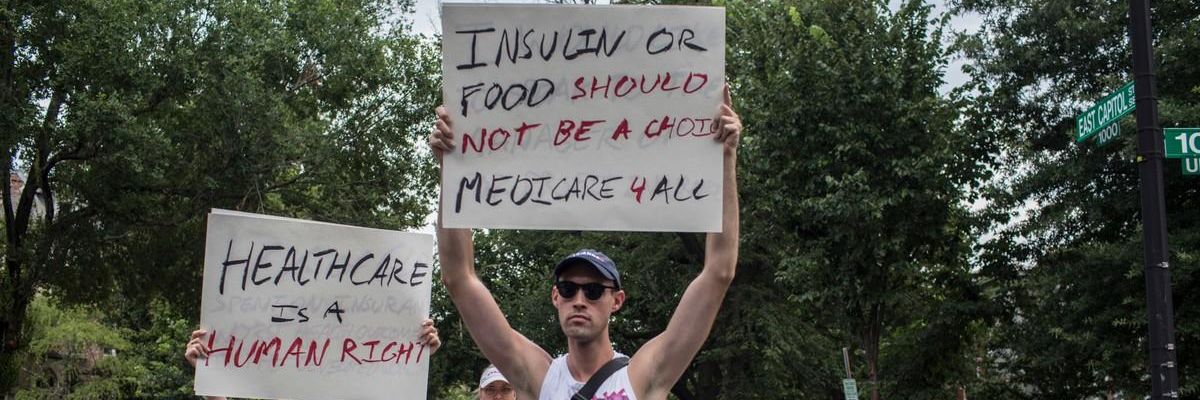

It’s time to put people over profit, and join #insulin4all advocates across the country in urging our state legislators to prioritize public pharma.