As Americans flock to Oppenheimer, one salutary result is a reawakened public awareness of the perils of nuclear weapons, and revived attention to the U.S. decision to bomb Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945). Less apparent is the extraordinary suffering of Japanese civilians and the appalling failure of the Truman administration to consider policy alternatives.

This inattention mirrors the public’s perception at the time, a pattern which has persisted over decades, as the U.S. government strikes countries from the air.

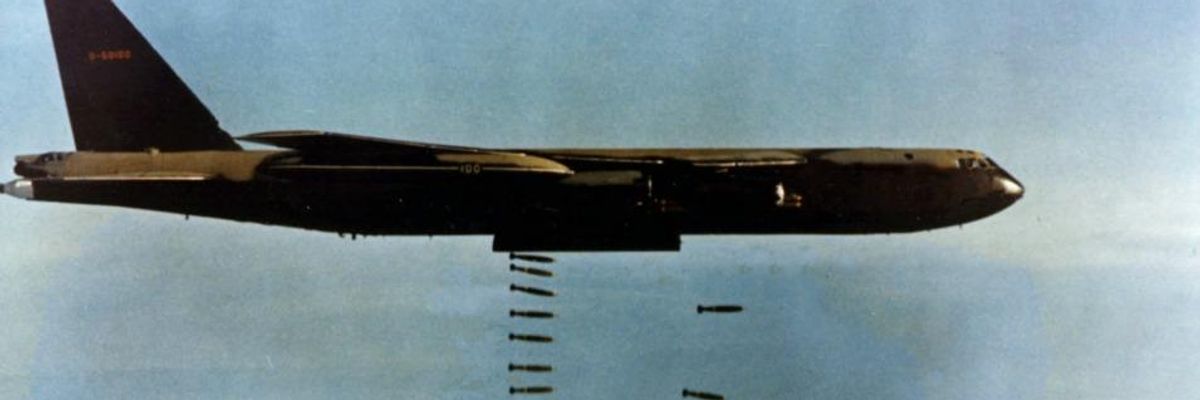

Long forgotten, and largely unnoticed in America, was the accidental bombing on August 6, 1973, by American B-52s of the center of Neak Luong, a ferry and garrison town inside Cambodia. It had fallen most heavily near barracks, where pro-government soldiers resided with their wives and children, damaging the local hospital and demolishing large sections of the town.

“Let the Americans see me,” mourned the anguished Cambodian soldier.

New York Times correspondent Sydney Schanberg encountered the victims as they were carried to the Preah Ket Mealea hospital in Phnom Penh. As he described it, “there were scenes of blood and weeping. Infants shattered by shrapnel, lay unconscious on stretchers.” Whole families had been affected. Walking along the riverbank, he observed a Cambodian soldier sobbing uncontrollably: “All my family is dead. .All my family is dead…Take my picture! Let the Americans see me.”

At the American Embassy, Colonel David Opfer was assuring the press that “the destruction was minimal,” although more than 200 people had died. As was routinely the case, whether in South Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia, government officials chose to deny or downplay the destruction.

Viewed in isolation, Neak Luong was a genuine accident. There was no intention to attack friendly soldiers and their families. However, this erroneous air strike was occurring in a context in which U.S. bombers had been striking Cambodia secretly and illegally for the past five years. Until that summer, the Nixon Administration had successfully concealed from Congress and the public their 3,600 bombing raids between March of 1969 and May of 1970.

Importantly, the attack on Neak Luong had occurred seven months after the January 1973 Paris Peace Accord had been signed, ostensibly ending U.S. participation in the Vietnam War. Although a specific Cambodian cease-fire was not included, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger had assured colleagues that based on understandings with Hanoi, fighting there would cease. Instead, the country was consumed by its own civil war between the Lon Nol government and the rapidly growing Khmer Rouge. As fighting continued, the United States kept bombing in support of the regime. The result was a six-month period more hellish than its predecessor, as much of the countryside became a virtual “free-fire zone,” for all participants.

This U.S. activity was of questionable legality, since under the Cooper-Church Amendment, the U.S. military was prohibited from bombing in support of the Cambodian government, except in response to North Vietnamese aggressor. In April 1973, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee sent two veteran observers, James Lowenstein and Richard Moose, on a fact-finding trip to Southeast Asia. Although assured by the Embassy and Air Force personnel that U.S. air strikes were to halt “the movement of North Vietnamese personnel, tanks, artillery, and supplies into South Vietnam,” they soon discovered the U.S. Embassy was coordinating the bombings, with an estimated 80% in support of Lon Nol’s regime.

Remarkably some American airmen responsible for the bombing were expressing their distress in letters to elected officials. These messages were so anguished, they were placed in the Congressional Record by Senator William Fulbright and given to The New York Times by Senator Edward Kennedy. According to one, “I am an AC-130 gunship navigator fighting the war in Cambodia on a day-to-day basis… What I see is an absurd effort by my Commander in Chief to preserve an unpopular, corrupt, dictatorial government at any expense. We have once again become involved in a civil conflict and because of our involvement have escalated the death and destruction on a massive scale.”

The careless killing of civilians did not end with the wars in Southeast Asia. One unfortunate lesson from that era was that a reliance on air power was politically safer than a large, extended deployment of American soldiers. Hence the “war on terrorism” waged in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere has involved tens of thousands of airstrikes whether by U.S. bombers or drones. Sadly, the tragic coda to the U.S. presence in Afghanistan was a hasty drone attack on August 29, 2021, that killed an innocent aid worker and seven children.

“Let the Americans see me,” mourned the anguished Cambodian soldier. While the case of Neak Luong was carefully reported, as was the misdirected drone attack in Kabul, these were the exceptions. Largely unaware of the existence or consequences of these air wars, the public has had little appetite or interest in policy alternatives. This remains a daunting challenge for the peace movement: how to make visible the ongoing practice of striking alleged enemies, with no accountability.