SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

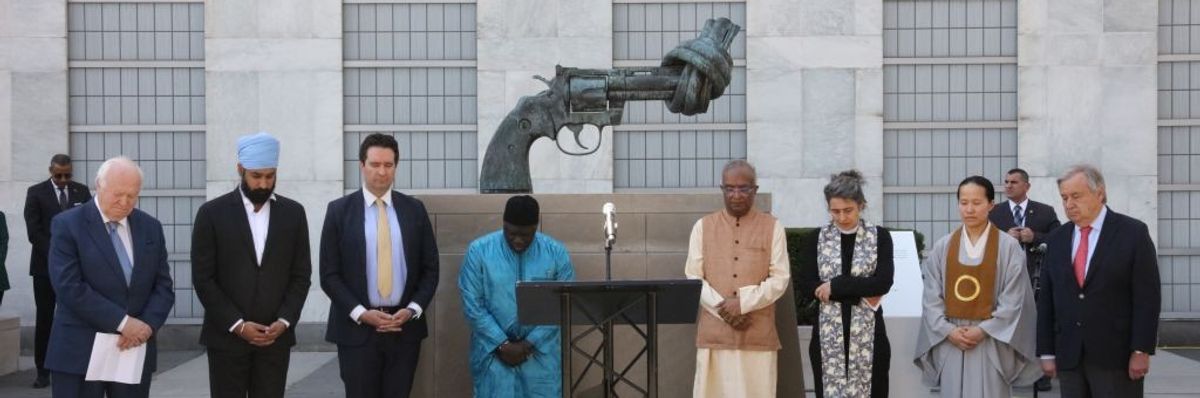

An interfaith moment of prayer for peace at a special time on the spiritual calendar is held at the U.N. headquarters in New York, on April 14, 2023. The world body on Friday held the interfaith moment of prayer for peace at a special time on the spiritual calendar, when Christians are celebrating Easter, Jews are marking Passover, Muslims are observing the holy month of Ramadan, and Sikhs are celebrating Vaisakhi.

As Muslims "reset" their daily lives during the holy month, the rest of the world should turn away from anti-Muslim racism.

Nearly every evening during Ramadan, mosques, community centers, and homes are filled with Muslims of every age, color, size, and shape. Many are fasting, some are not. When sunset hits, they eat dates, recite prayers, and enjoy the camaraderie of a communal meal. The roughly 3.5 million followers of Islam in the U.S. and two billion around the world will do this every day for a month.

As someone who grew up in a Muslim community, the majority of Muslims I have known are decent, hard-working, law-abiding, community-oriented people. Many are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants. Some have lived in the U.S. for generations, others for a few weeks. And yet, more than 20 years post 9/11, anti-Muslim sentiments and stereotypes about Muslims run high.

This is not just a U.S. problem. At a mosque outside Toronto recently, a man shouted Islamophobic slurs and tried to run over congregants, raising concerns about increasing hatred toward Canadian Muslims and prompting mosque officials to call for government action to better protect faith communities. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's latest attack involves erasing the country's Muslim past from new history textbooks.

It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

And in China, police are once again using spies to make sure Uyghur Muslims are not fasting during the holy month. Chinese authorities have imprisoned more than one million Uyghurs in “re-education centers” to diminish their culture, language, and religion; it has been nearly a decade since China began its systematic campaign of human rights abuses against the minority ethnic group.

Negative attitudes toward Muslims have had disastrous consequences even in Muslim-majority countries. Islam is the second largest and fastest growing religion in the world. There are approximately 50 countries where Muslims make up at least half of the population and 30 where Muslims make up 90 percent or more. Yet like Muslims and those who “look Muslim” in the West, many of these nations have become targets of an endless war on terror.

In her book Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, Deepa Kumar argues that anti-Muslim sentiment operates like racism. It is socially constructed and a product of imperialism aimed to produce, sustain, and in turn be fed by the U.S. and its allies. For example, by spreading the false ideology that Islam is a monolith, it's easier to claim that everyone who practices Islam is driven to violence, or that Islam is inherently anti-modern and sexist. There are actually as many as 73 diverse sects, and progressive Muslim groups that advocate for human rights, social justice, and inclusion.

Last year, in recognition of anti-Muslim racism and hatred, the United Nations declared March 15 as the International Day to Combat Islamophobia. However, Muslims around the world still confront ignorance about their religion and discrimination on a regular basis. It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

Many of my family members and friends are part of the Muslim community. Especially during Ramadan, we try to learn from the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and follow principles of Islam that will make us more helpful, kind, selfless, humble, forgiving, and empathetic humans.

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars, or key practices, of Islam. If they are able, Muslims are urged to abstain from eating and drinking between dawn and sunset. It's a collective practice where people share the hardships and rewards of the month—hunger, thirst, sleep deprivation, exhaustion, altruism, empathy, and enlightenment.

I personally try to use Ramadan as a time to break from my usual schedule and reset. I strive to be more patient, mindful, and spiritual, and less preoccupied with meaningless distractions. I find that I empathize more with people who have less, because that's what happens when my stomach is empty.

Ramadan follows the lunar Islamic calendar, which means it moves back by around ten days each year of the solar Gregorian calendar. This year, it coincided with Passover and Easter, one of the rare times when holidays marked by family, food, and spirituality from three major religions overlap.

The last ten days of Ramadan hold particular significance because that's when the holy Qur'an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. As the holy month comes to an end, a diverse array of Muslims around the world will be immersed in prayer, reflection, and acts of service.

I will be among them, hopeful that the year ahead will bring increased tolerance toward a faith community of people who have for too long been targets of misinformation and ignorance.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Nearly every evening during Ramadan, mosques, community centers, and homes are filled with Muslims of every age, color, size, and shape. Many are fasting, some are not. When sunset hits, they eat dates, recite prayers, and enjoy the camaraderie of a communal meal. The roughly 3.5 million followers of Islam in the U.S. and two billion around the world will do this every day for a month.

As someone who grew up in a Muslim community, the majority of Muslims I have known are decent, hard-working, law-abiding, community-oriented people. Many are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants. Some have lived in the U.S. for generations, others for a few weeks. And yet, more than 20 years post 9/11, anti-Muslim sentiments and stereotypes about Muslims run high.

This is not just a U.S. problem. At a mosque outside Toronto recently, a man shouted Islamophobic slurs and tried to run over congregants, raising concerns about increasing hatred toward Canadian Muslims and prompting mosque officials to call for government action to better protect faith communities. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's latest attack involves erasing the country's Muslim past from new history textbooks.

It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

And in China, police are once again using spies to make sure Uyghur Muslims are not fasting during the holy month. Chinese authorities have imprisoned more than one million Uyghurs in “re-education centers” to diminish their culture, language, and religion; it has been nearly a decade since China began its systematic campaign of human rights abuses against the minority ethnic group.

Negative attitudes toward Muslims have had disastrous consequences even in Muslim-majority countries. Islam is the second largest and fastest growing religion in the world. There are approximately 50 countries where Muslims make up at least half of the population and 30 where Muslims make up 90 percent or more. Yet like Muslims and those who “look Muslim” in the West, many of these nations have become targets of an endless war on terror.

In her book Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, Deepa Kumar argues that anti-Muslim sentiment operates like racism. It is socially constructed and a product of imperialism aimed to produce, sustain, and in turn be fed by the U.S. and its allies. For example, by spreading the false ideology that Islam is a monolith, it's easier to claim that everyone who practices Islam is driven to violence, or that Islam is inherently anti-modern and sexist. There are actually as many as 73 diverse sects, and progressive Muslim groups that advocate for human rights, social justice, and inclusion.

Last year, in recognition of anti-Muslim racism and hatred, the United Nations declared March 15 as the International Day to Combat Islamophobia. However, Muslims around the world still confront ignorance about their religion and discrimination on a regular basis. It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

Many of my family members and friends are part of the Muslim community. Especially during Ramadan, we try to learn from the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and follow principles of Islam that will make us more helpful, kind, selfless, humble, forgiving, and empathetic humans.

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars, or key practices, of Islam. If they are able, Muslims are urged to abstain from eating and drinking between dawn and sunset. It's a collective practice where people share the hardships and rewards of the month—hunger, thirst, sleep deprivation, exhaustion, altruism, empathy, and enlightenment.

I personally try to use Ramadan as a time to break from my usual schedule and reset. I strive to be more patient, mindful, and spiritual, and less preoccupied with meaningless distractions. I find that I empathize more with people who have less, because that's what happens when my stomach is empty.

Ramadan follows the lunar Islamic calendar, which means it moves back by around ten days each year of the solar Gregorian calendar. This year, it coincided with Passover and Easter, one of the rare times when holidays marked by family, food, and spirituality from three major religions overlap.

The last ten days of Ramadan hold particular significance because that's when the holy Qur'an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. As the holy month comes to an end, a diverse array of Muslims around the world will be immersed in prayer, reflection, and acts of service.

I will be among them, hopeful that the year ahead will bring increased tolerance toward a faith community of people who have for too long been targets of misinformation and ignorance.

Nearly every evening during Ramadan, mosques, community centers, and homes are filled with Muslims of every age, color, size, and shape. Many are fasting, some are not. When sunset hits, they eat dates, recite prayers, and enjoy the camaraderie of a communal meal. The roughly 3.5 million followers of Islam in the U.S. and two billion around the world will do this every day for a month.

As someone who grew up in a Muslim community, the majority of Muslims I have known are decent, hard-working, law-abiding, community-oriented people. Many are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants. Some have lived in the U.S. for generations, others for a few weeks. And yet, more than 20 years post 9/11, anti-Muslim sentiments and stereotypes about Muslims run high.

This is not just a U.S. problem. At a mosque outside Toronto recently, a man shouted Islamophobic slurs and tried to run over congregants, raising concerns about increasing hatred toward Canadian Muslims and prompting mosque officials to call for government action to better protect faith communities. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's latest attack involves erasing the country's Muslim past from new history textbooks.

It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

And in China, police are once again using spies to make sure Uyghur Muslims are not fasting during the holy month. Chinese authorities have imprisoned more than one million Uyghurs in “re-education centers” to diminish their culture, language, and religion; it has been nearly a decade since China began its systematic campaign of human rights abuses against the minority ethnic group.

Negative attitudes toward Muslims have had disastrous consequences even in Muslim-majority countries. Islam is the second largest and fastest growing religion in the world. There are approximately 50 countries where Muslims make up at least half of the population and 30 where Muslims make up 90 percent or more. Yet like Muslims and those who “look Muslim” in the West, many of these nations have become targets of an endless war on terror.

In her book Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, Deepa Kumar argues that anti-Muslim sentiment operates like racism. It is socially constructed and a product of imperialism aimed to produce, sustain, and in turn be fed by the U.S. and its allies. For example, by spreading the false ideology that Islam is a monolith, it's easier to claim that everyone who practices Islam is driven to violence, or that Islam is inherently anti-modern and sexist. There are actually as many as 73 diverse sects, and progressive Muslim groups that advocate for human rights, social justice, and inclusion.

Last year, in recognition of anti-Muslim racism and hatred, the United Nations declared March 15 as the International Day to Combat Islamophobia. However, Muslims around the world still confront ignorance about their religion and discrimination on a regular basis. It's time to deconstruct the self-serving systems that benefit from preserving the status quo and to debunk ideologies that perpetuate negative stereotypes about Muslims and anti-Muslim racism.

Many of my family members and friends are part of the Muslim community. Especially during Ramadan, we try to learn from the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and follow principles of Islam that will make us more helpful, kind, selfless, humble, forgiving, and empathetic humans.

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars, or key practices, of Islam. If they are able, Muslims are urged to abstain from eating and drinking between dawn and sunset. It's a collective practice where people share the hardships and rewards of the month—hunger, thirst, sleep deprivation, exhaustion, altruism, empathy, and enlightenment.

I personally try to use Ramadan as a time to break from my usual schedule and reset. I strive to be more patient, mindful, and spiritual, and less preoccupied with meaningless distractions. I find that I empathize more with people who have less, because that's what happens when my stomach is empty.

Ramadan follows the lunar Islamic calendar, which means it moves back by around ten days each year of the solar Gregorian calendar. This year, it coincided with Passover and Easter, one of the rare times when holidays marked by family, food, and spirituality from three major religions overlap.

The last ten days of Ramadan hold particular significance because that's when the holy Qur'an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. As the holy month comes to an end, a diverse array of Muslims around the world will be immersed in prayer, reflection, and acts of service.

I will be among them, hopeful that the year ahead will bring increased tolerance toward a faith community of people who have for too long been targets of misinformation and ignorance.