It took 69 years, but last week the U.S. Supreme Court took its revenge on Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark case that cracked the door a smidge to desegregating schools.

Revenge, not reversal, because the decision all but ending affirmative action in college admissions doesn’t erase Brown. It pretends that Brown no longer needs to exist. It returns the country to the days when race couldn’t be denied, necessarily–whites have never denied their race–but that the other person’s racial identity could be. It makes color-blindness national policy, as long as whites wear the blinders.

Since whites still control the overwhelming majority of levers, but with no affirmative balancing factors to worry about anymore, it’s simply math how this will go. The vengeful feel of the decision is in Justice Roberts’s cynical use of stats when he cited the plaintiffs saying that “over 80% of all black applicants in the top academic decile were admitted to UNC, while under 70% of white and Asian applicants in that decile were admitted,” never citing, of course that at UNC, a state school in a state where 22 percent of the population is Black, 59 percent of the student body is white, and just 8 percent Black. That omission “blinks reality,” to use the words he used against a dissenter in the same footnote.

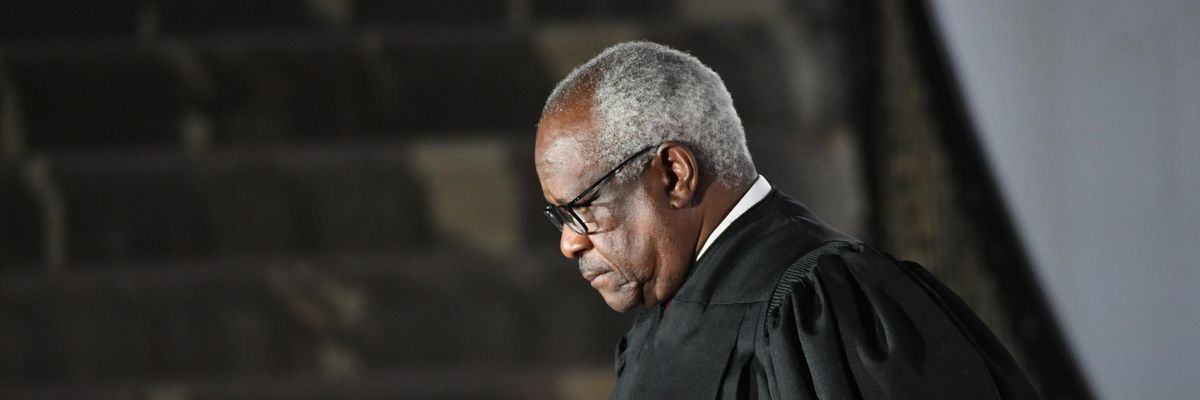

The vengeful shade of the decision is in the deceptively Pledgy with-liberty-and-justice-for-all tone that Justice Thomas adopted in his concurrence, either as he sneered with Heritage Foundation-shaped quote marks at the word equity, or as he invoked the ideals of Reconstruction: “the solution announced in the second founding is incorporated in our Constitution: that we are all equal, and should be treated equally before the law without regard to our race.”

But the language is tuned to the same motives behind the John Birch Society’s “Impeach Earl Warren” billboards that invaded the South in reaction to Brown, much to the joy of segregationists everywhere: to stop diversity’s progress by pretending that constitutional language is enough not to impede it.

So like Justice Scalia’s magically realist invention of an individual right to bear arms in the 2008 Heller decision, today’s decision is not a legal one, exactly. It builds on fictions such as Sandra Day O’Connort’s from the 2003 case that the justices almost overturned today, when she claimed that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest” of diversity.

At the time, O’Connor sounded like a Sybil foretelling the coming deliverance. In retrospect, and with her black robe made of the same cloth that hid the Wizard of Oz, she sounds more like the clever clairvoyance of Nostradamus. (At least George Orwell, no stranger to prophesies, had the good sense to preface his predictions with a disclaimer: “All prophesies are wrong, therefore this one will be wrong.”)

Then came Justice Roberts’s hyper-fictions, first with his bumper-sticker tautology in 2007 that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” The statement was as nonsensical as those commercials for hemorrhoidal cream showing freckled middle aged women happily swimming in a pool or hiking the Grand Canyon, presumably itchless. There’s no relationship between Preparation H and the images shown, just as there’s no earthly connection between the first and second clause of Roberts’s statement. But it sent conservatives swooning because it had that oracular ring of fortune cookies that gag further inquiry.

Roberts did it again last week when he wrote that a student “must be treated based on his or her experience as an individual–not on the basis of race.” (This from a court that–using the same Amendment on which it based the decision–defines corporations as persons, a court that considers ExxonMobil or Microsoft as singly individual as your neighbor or mine.)

Roberts, in this blinkered view of individuality, is saying that race in one’s experience is incidental, not controlling. He is speaking from experience: his experience. He is speaking as only a white, entitled, privileged American can speak, a white American to whom race is incidental, in a country where nothing is incidental when you’re not white. Not often, anyway. Not so often that Howard Zinn’s observation would be outdated, as Roberts wishes it to be: “There is not a country in world history,” Zinn wrote, “in which racism has been more important, for so long a time, as in the United States.”

There is some idealism in last week's decision. We want to think that judging anyone by their character rather than the color of their skin—or their ethnic origin, their gender, their religious creed, their zip code, their name, their wealth—is who and how we are. We instinctively want to incline to equality in those regards, at least when we deliver speeches before the Rotary or the chamber of commerce.

There’s a discomfort in knowing that anyone would get an advantage not because of innate merit, but because of the luck of birth’s draw. There’s plenty of room for disdaining the condescension and paternalism of what Justice Thomas 20 years ago, before he got his revenge, referred to as the “fashionable catchphrase” of diversity, which can demean the very people it is intended help as much as it can uplift.

But that’s not saying much more than the obvious. We are an imperfect union, founded on an imperfect document still very far from being achieved, even in its numerous imperfections. Affirmative action was one of those correctives as surely as the second founding, and the third, were others.

That’s what Gerald Ford, 23 years out of the presidency, thought in 1999 when he decried the lawsuit seeking to end the use of race as a factor at the University of Michigan, his own alma mater. “At its core, affirmative action should try to offset past injustices by fashioning a campus population more truly reflective of modern America and our hopes for the future,” he’d written simply. “To eliminate a constitutional affirmative action policy would mock the inclusive vision Carl Sandburg had in mind when he wrote: ‘The Republic is a dream. Nothing happens unless first a dream.’ Lest we forget: America remains a nation with have-nots as well as haves. Its government is obligated to provide for hope no less than for the common defense.”

Affirmative action survived then. That’s the precedent the justices un-achieved in this ignominious ruling.