Legal Defense Fund attorney Deuel Ross speaks to journalists after oral arguments for Merrill v. Milligan—later Allen v. Milligan—at the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. on October 4, 2022.

Supreme Court Voting Rights Decision an Important, If Qualified, Win

While Allen v. Milligan should be celebrated as a victory for fair representation, it cannot be an excuse for congressional inaction.

Black voters in Alabama won a victory at the Supreme Court Thursday with a narrow 5-4 ruling written by Chief Justice John Roberts holding that state lawmakers violated the Voting Rights Act when they redrew Alabama’s congressional map after the 2020 census.

The decision is an important, if qualified, win for voting rights advocates. If the high court had done what Alabama and conservative groups had asked—and what the dissenting justices wanted—it would have radically rewritten or even eliminated one of the few remaining protections of the Voting Rights Act.

At the heart of the case, Allen v. Milligan, was the question of whether the congressional map adopted by lawmakers illegally diluted Black political power when it divided communities in Alabama’s mostly rural and heavily impoverished Black Belt region among five different districts.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become.

Under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters can sue to force states or localities to change voting maps if they can show that racially polarized voting interacts with the design of maps to make it impossible for minority communities to win political power. That’s exactly what Black voters argued happened in Alabama.

Under the legislature’s map, although Black voters are a substantial majority in the 7th Congressional District on the western side of the state, represented by Democrat Terri Sewell, they are 30% or less of the population in the region’s other four districts. Given Alabama’s long history of starkly racially polarized voting, this careful “ packing and cracking” has the effect of ensuring that Black voters are always shut out of power except where they are a majority or near majority. While in many other parts of the country, a lack of racially polarized voting means minority voters can win power through the hard work of building multiracial coalitions, that simply isn’t possible under current circumstances in Alabama. Six decades after the end of Jim Crow, white and Black Alabamians continue to prefer completely different candidates—strongly and unwaveringly so.

A three-judge trial court that included two appointees of President Donald Trumpunanimously agreed with Black voters, ordering Alabama to redraw its map to create two districts “where Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

Alabama appealed, claiming that it could not create a second Black district without violating lawmakers’ stated policy preference for changing districts as little as possible in redistricting, including making sure counties along the state’s Gulf Coast were kept whole within the same district. It also urged the high court to throw out long-established precedents and adopt a “race-neutral benchmark” for judging what the appropriate number of minority districts should be.

Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the court’s three liberal justices, forcefully rejected what they described as “Alabama’s attempt to remake our §2 jurisprudence anew.” Under Alabama’s approach, the court said “a State could immunize from challenge a new racially discriminatory redistricting plan simply by claiming that it resembled an old racially discriminatory plan.”

The Court also noted that evidence in the case did not establish that keeping Gulf Coast counties together should be a higher priority than keeping the Black Belt together, describing the region as a community of interest with “a high proportion of Black voters who ‘share a rural geography, concentrated poverty, unequal access to government services,... lack of adequate healthcare,’ and a lineal connection to ‘the many enslaved people brought there to work in the antebellum period.’”

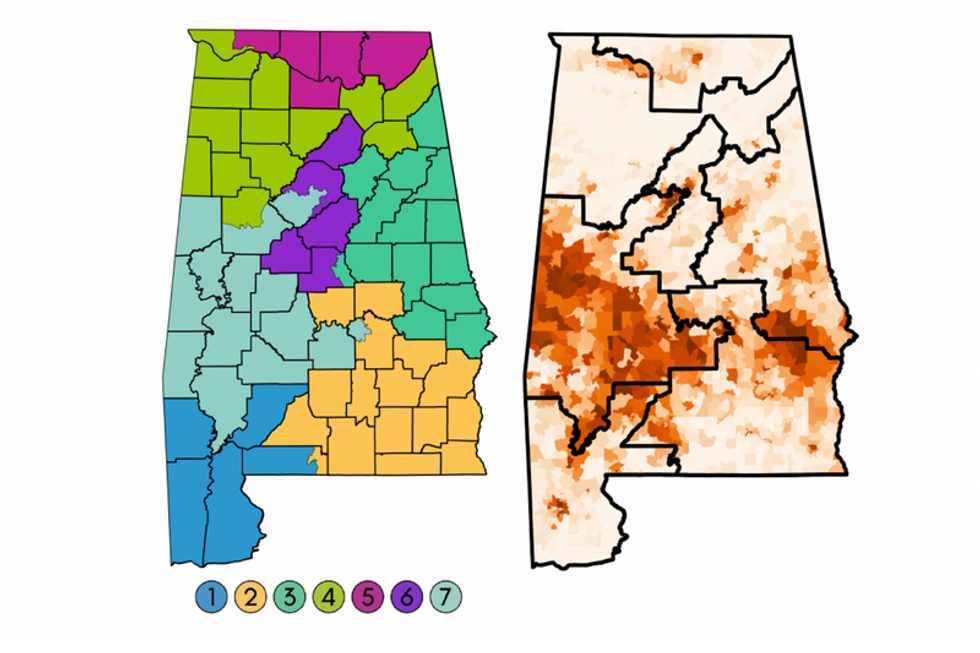

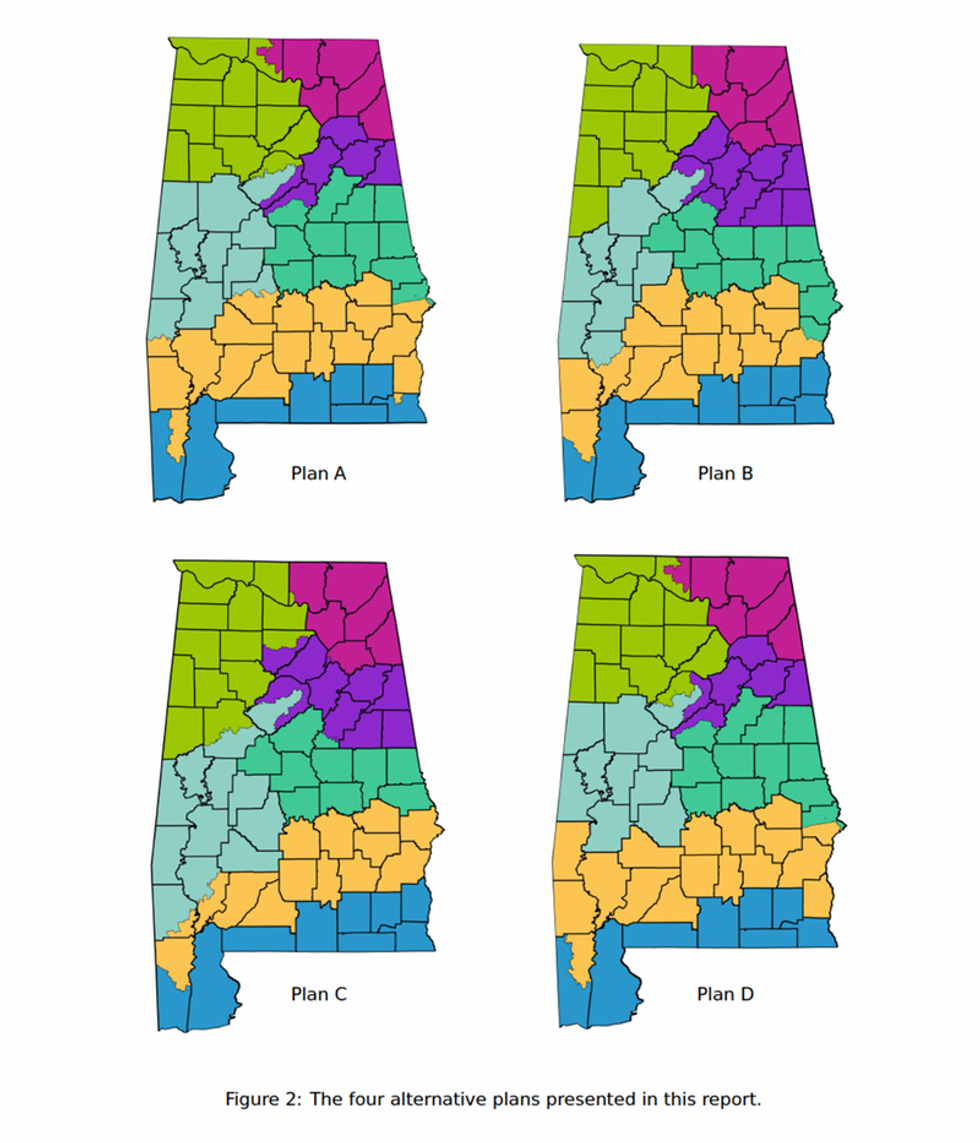

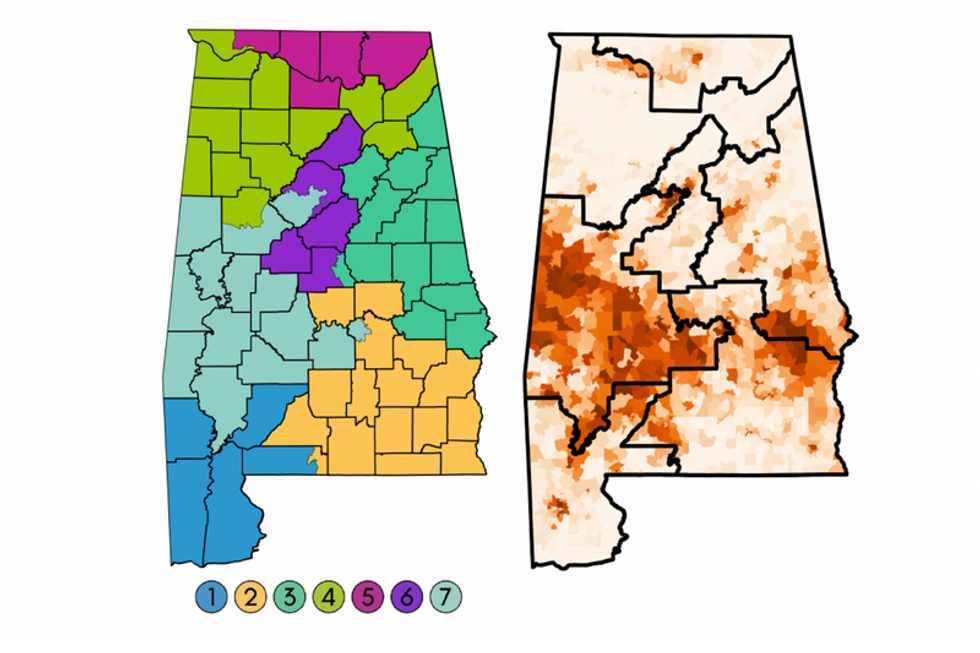

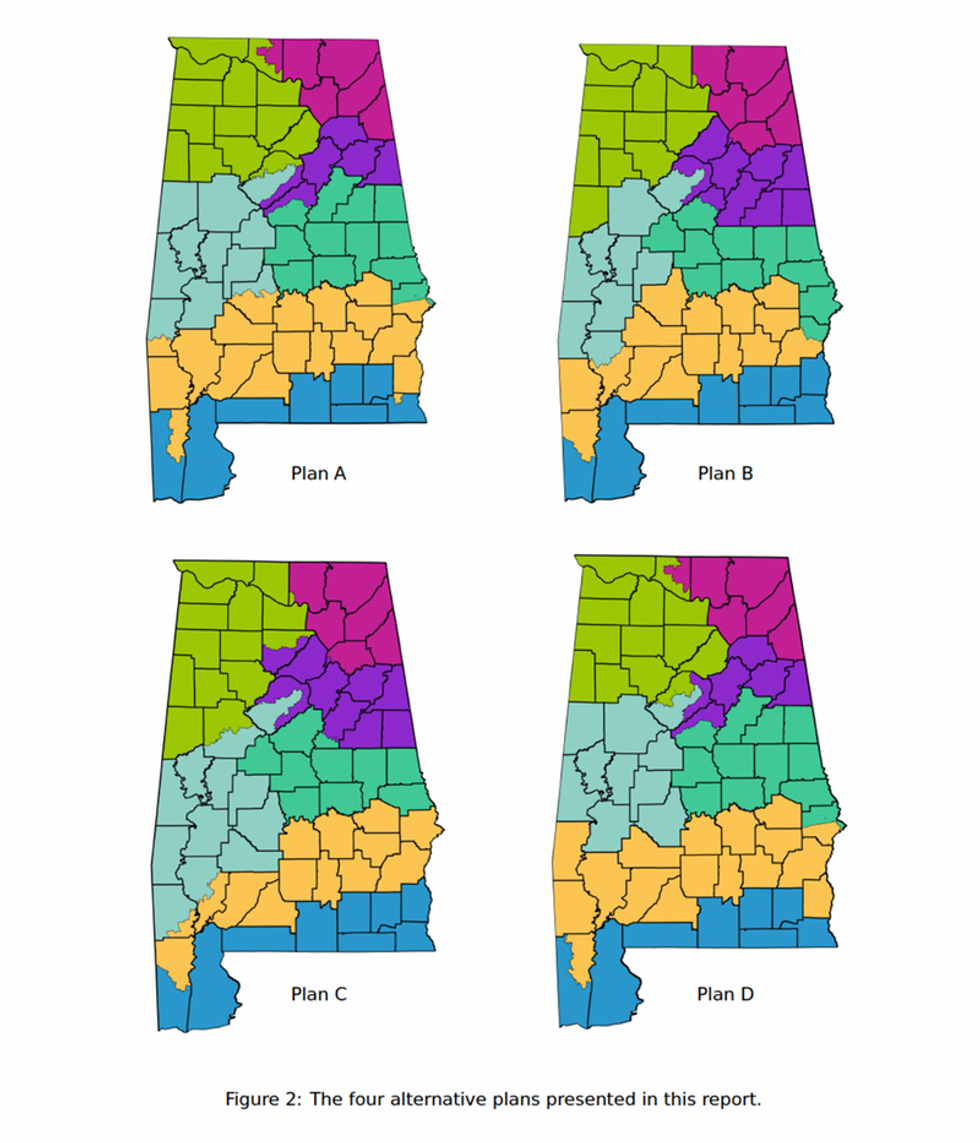

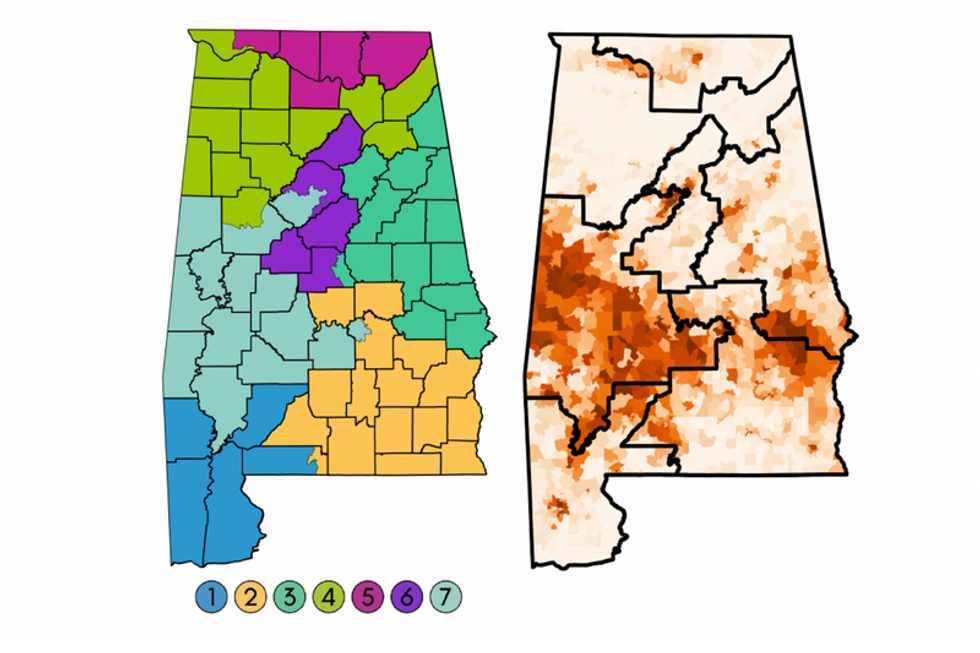

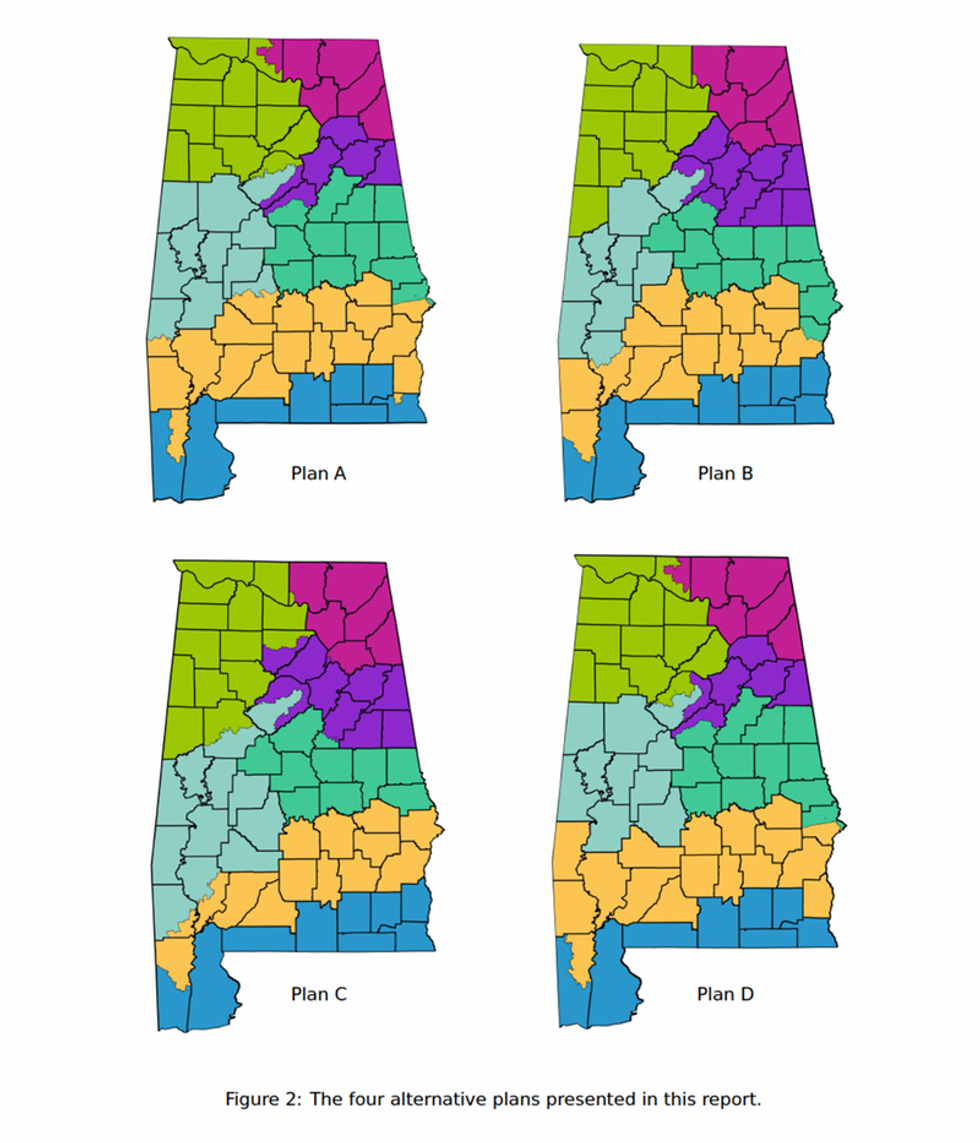

Instead, the Court said that the trial court had “faithfully applied our precedents and correctly determined” that the Voting Rights Act required creation of a second district where Black voters had a reasonable opportunity to be politically successful. Roberts suggested this should be easy to do given that the “plaintiffs adduced eleven illustrative maps—that is, example districting maps that Alabama could enact—each of which contained two majority-black districts that comported with traditional districting criteria” and that were more compact, on average, than the state’s map. (The yellow districts in the maps below from an expert report presented to the trial court are just four examples of how the new district could be configured.)

The ruling will reverberate across the country. The most immediate impact is likely to be in Louisiana, where last year a federal district court ordered the state’s congressional map to be redrawn to create an additional Black district. The Supreme Court put that ruling on hold pending resolution of the Alabama case, but is expected in the coming days to send the case back to the trial court. Likewise, in Georgia, a court will hold hearings this fall on claims that the Voting Rights Act requires redrawing of Georgia’s congressional map to create an additional Black district. Along with Alabama, these states could see new maps in time for the 2024 elections.

The ruling will also affect roughly three dozen other ongoing Section 2 cases around the country, ranging from challenges to Texas’s congressional map to lawsuits over city council districts in Dodge City, Kansas, and county commission districts in Thurston County, Nebraska. However, many of these cases are not as far along as the cases in Louisiana and Georgia, and it remains to be seen whether this second group of cases, including their inevitable appeals, can be resolved before the next election.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become. The Milligan opinion itself notes that in recent years, Section 2 lawsuits have only “rarely been successful,” with fewer than a dozen Section 2 victories since 2010 at any level of government, including school boards and city councils.

Indeed, for years, the Supreme Court has been slowly but steadily eroding the robustness of Section 2, for example by imposing compactness and demographic requirements that act in tandem to make it harder for plaintiffs to win relief from racially discriminatory maps in the diverse, multi-ethnic communities where Americans increasingly live.

And, even where Section 2 plaintiffs succeed, as Alabama and Louisiana illustrate, courts often use the so-called Purcell principle and the excuse of an upcoming election to delay the redrawing of maps, effectively giving discriminatory line drawers one free election and term of office to enact policy. While districts may ultimately be struck down, people must live with the consequences of elections under illegal maps. In short, even if the Supreme Court didn’t do as many feared and further whittle away at the Voting Rights Act, the status quo for voters, and minority voters in particular, remains deeply inadequate.

While Milligan should be celebrated as a win for fair representation, it cannot be an excuse for congressional inaction. This month marks the 10-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, a decision that gutted another key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In the decade since, Congress has tried and repeatedly failed to overcome legislative inertia to respond. Section 2 lives to fight another day, but the provision by itself is not—and never has been—enough. It is well past time to not only restore but strengthen the Voting Rights Act for a 21st-century America. Nothing less than the future of the country’s emerging multiracial democracy is at stake. Congress must act.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Black voters in Alabama won a victory at the Supreme Court Thursday with a narrow 5-4 ruling written by Chief Justice John Roberts holding that state lawmakers violated the Voting Rights Act when they redrew Alabama’s congressional map after the 2020 census.

The decision is an important, if qualified, win for voting rights advocates. If the high court had done what Alabama and conservative groups had asked—and what the dissenting justices wanted—it would have radically rewritten or even eliminated one of the few remaining protections of the Voting Rights Act.

At the heart of the case, Allen v. Milligan, was the question of whether the congressional map adopted by lawmakers illegally diluted Black political power when it divided communities in Alabama’s mostly rural and heavily impoverished Black Belt region among five different districts.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become.

Under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters can sue to force states or localities to change voting maps if they can show that racially polarized voting interacts with the design of maps to make it impossible for minority communities to win political power. That’s exactly what Black voters argued happened in Alabama.

Under the legislature’s map, although Black voters are a substantial majority in the 7th Congressional District on the western side of the state, represented by Democrat Terri Sewell, they are 30% or less of the population in the region’s other four districts. Given Alabama’s long history of starkly racially polarized voting, this careful “ packing and cracking” has the effect of ensuring that Black voters are always shut out of power except where they are a majority or near majority. While in many other parts of the country, a lack of racially polarized voting means minority voters can win power through the hard work of building multiracial coalitions, that simply isn’t possible under current circumstances in Alabama. Six decades after the end of Jim Crow, white and Black Alabamians continue to prefer completely different candidates—strongly and unwaveringly so.

A three-judge trial court that included two appointees of President Donald Trumpunanimously agreed with Black voters, ordering Alabama to redraw its map to create two districts “where Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

Alabama appealed, claiming that it could not create a second Black district without violating lawmakers’ stated policy preference for changing districts as little as possible in redistricting, including making sure counties along the state’s Gulf Coast were kept whole within the same district. It also urged the high court to throw out long-established precedents and adopt a “race-neutral benchmark” for judging what the appropriate number of minority districts should be.

Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the court’s three liberal justices, forcefully rejected what they described as “Alabama’s attempt to remake our §2 jurisprudence anew.” Under Alabama’s approach, the court said “a State could immunize from challenge a new racially discriminatory redistricting plan simply by claiming that it resembled an old racially discriminatory plan.”

The Court also noted that evidence in the case did not establish that keeping Gulf Coast counties together should be a higher priority than keeping the Black Belt together, describing the region as a community of interest with “a high proportion of Black voters who ‘share a rural geography, concentrated poverty, unequal access to government services,... lack of adequate healthcare,’ and a lineal connection to ‘the many enslaved people brought there to work in the antebellum period.’”

Instead, the Court said that the trial court had “faithfully applied our precedents and correctly determined” that the Voting Rights Act required creation of a second district where Black voters had a reasonable opportunity to be politically successful. Roberts suggested this should be easy to do given that the “plaintiffs adduced eleven illustrative maps—that is, example districting maps that Alabama could enact—each of which contained two majority-black districts that comported with traditional districting criteria” and that were more compact, on average, than the state’s map. (The yellow districts in the maps below from an expert report presented to the trial court are just four examples of how the new district could be configured.)

The ruling will reverberate across the country. The most immediate impact is likely to be in Louisiana, where last year a federal district court ordered the state’s congressional map to be redrawn to create an additional Black district. The Supreme Court put that ruling on hold pending resolution of the Alabama case, but is expected in the coming days to send the case back to the trial court. Likewise, in Georgia, a court will hold hearings this fall on claims that the Voting Rights Act requires redrawing of Georgia’s congressional map to create an additional Black district. Along with Alabama, these states could see new maps in time for the 2024 elections.

The ruling will also affect roughly three dozen other ongoing Section 2 cases around the country, ranging from challenges to Texas’s congressional map to lawsuits over city council districts in Dodge City, Kansas, and county commission districts in Thurston County, Nebraska. However, many of these cases are not as far along as the cases in Louisiana and Georgia, and it remains to be seen whether this second group of cases, including their inevitable appeals, can be resolved before the next election.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become. The Milligan opinion itself notes that in recent years, Section 2 lawsuits have only “rarely been successful,” with fewer than a dozen Section 2 victories since 2010 at any level of government, including school boards and city councils.

Indeed, for years, the Supreme Court has been slowly but steadily eroding the robustness of Section 2, for example by imposing compactness and demographic requirements that act in tandem to make it harder for plaintiffs to win relief from racially discriminatory maps in the diverse, multi-ethnic communities where Americans increasingly live.

And, even where Section 2 plaintiffs succeed, as Alabama and Louisiana illustrate, courts often use the so-called Purcell principle and the excuse of an upcoming election to delay the redrawing of maps, effectively giving discriminatory line drawers one free election and term of office to enact policy. While districts may ultimately be struck down, people must live with the consequences of elections under illegal maps. In short, even if the Supreme Court didn’t do as many feared and further whittle away at the Voting Rights Act, the status quo for voters, and minority voters in particular, remains deeply inadequate.

While Milligan should be celebrated as a win for fair representation, it cannot be an excuse for congressional inaction. This month marks the 10-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, a decision that gutted another key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In the decade since, Congress has tried and repeatedly failed to overcome legislative inertia to respond. Section 2 lives to fight another day, but the provision by itself is not—and never has been—enough. It is well past time to not only restore but strengthen the Voting Rights Act for a 21st-century America. Nothing less than the future of the country’s emerging multiracial democracy is at stake. Congress must act.

- With Support of Just One Republican, House Passes 'Historic' Bill to Restore and Expand Voting Rights ›

- 'Huge Surprise' as US Supreme Court Declines to Further Gut Voting Rights Act ›

- Blaring Quiet Part Out Loud, GOP Lawyer Admits to Supreme Court That Easier Voting Puts Republicans at 'Competitive Disadvantage' ›

Black voters in Alabama won a victory at the Supreme Court Thursday with a narrow 5-4 ruling written by Chief Justice John Roberts holding that state lawmakers violated the Voting Rights Act when they redrew Alabama’s congressional map after the 2020 census.

The decision is an important, if qualified, win for voting rights advocates. If the high court had done what Alabama and conservative groups had asked—and what the dissenting justices wanted—it would have radically rewritten or even eliminated one of the few remaining protections of the Voting Rights Act.

At the heart of the case, Allen v. Milligan, was the question of whether the congressional map adopted by lawmakers illegally diluted Black political power when it divided communities in Alabama’s mostly rural and heavily impoverished Black Belt region among five different districts.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become.

Under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters can sue to force states or localities to change voting maps if they can show that racially polarized voting interacts with the design of maps to make it impossible for minority communities to win political power. That’s exactly what Black voters argued happened in Alabama.

Under the legislature’s map, although Black voters are a substantial majority in the 7th Congressional District on the western side of the state, represented by Democrat Terri Sewell, they are 30% or less of the population in the region’s other four districts. Given Alabama’s long history of starkly racially polarized voting, this careful “ packing and cracking” has the effect of ensuring that Black voters are always shut out of power except where they are a majority or near majority. While in many other parts of the country, a lack of racially polarized voting means minority voters can win power through the hard work of building multiracial coalitions, that simply isn’t possible under current circumstances in Alabama. Six decades after the end of Jim Crow, white and Black Alabamians continue to prefer completely different candidates—strongly and unwaveringly so.

A three-judge trial court that included two appointees of President Donald Trumpunanimously agreed with Black voters, ordering Alabama to redraw its map to create two districts “where Black voters either comprise a voting-age majority or something quite close to it.”

Alabama appealed, claiming that it could not create a second Black district without violating lawmakers’ stated policy preference for changing districts as little as possible in redistricting, including making sure counties along the state’s Gulf Coast were kept whole within the same district. It also urged the high court to throw out long-established precedents and adopt a “race-neutral benchmark” for judging what the appropriate number of minority districts should be.

Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the court’s three liberal justices, forcefully rejected what they described as “Alabama’s attempt to remake our §2 jurisprudence anew.” Under Alabama’s approach, the court said “a State could immunize from challenge a new racially discriminatory redistricting plan simply by claiming that it resembled an old racially discriminatory plan.”

The Court also noted that evidence in the case did not establish that keeping Gulf Coast counties together should be a higher priority than keeping the Black Belt together, describing the region as a community of interest with “a high proportion of Black voters who ‘share a rural geography, concentrated poverty, unequal access to government services,... lack of adequate healthcare,’ and a lineal connection to ‘the many enslaved people brought there to work in the antebellum period.’”

Instead, the Court said that the trial court had “faithfully applied our precedents and correctly determined” that the Voting Rights Act required creation of a second district where Black voters had a reasonable opportunity to be politically successful. Roberts suggested this should be easy to do given that the “plaintiffs adduced eleven illustrative maps—that is, example districting maps that Alabama could enact—each of which contained two majority-black districts that comported with traditional districting criteria” and that were more compact, on average, than the state’s map. (The yellow districts in the maps below from an expert report presented to the trial court are just four examples of how the new district could be configured.)

The ruling will reverberate across the country. The most immediate impact is likely to be in Louisiana, where last year a federal district court ordered the state’s congressional map to be redrawn to create an additional Black district. The Supreme Court put that ruling on hold pending resolution of the Alabama case, but is expected in the coming days to send the case back to the trial court. Likewise, in Georgia, a court will hold hearings this fall on claims that the Voting Rights Act requires redrawing of Georgia’s congressional map to create an additional Black district. Along with Alabama, these states could see new maps in time for the 2024 elections.

The ruling will also affect roughly three dozen other ongoing Section 2 cases around the country, ranging from challenges to Texas’s congressional map to lawsuits over city council districts in Dodge City, Kansas, and county commission districts in Thurston County, Nebraska. However, many of these cases are not as far along as the cases in Louisiana and Georgia, and it remains to be seen whether this second group of cases, including their inevitable appeals, can be resolved before the next election.

But if the decision didn’t further dismantle voting rights protections, it also didn’t strengthen them. In many ways, in fact, the win in Milligan spotlights how thin the tools for fighting discriminatory line drawing have become. The Milligan opinion itself notes that in recent years, Section 2 lawsuits have only “rarely been successful,” with fewer than a dozen Section 2 victories since 2010 at any level of government, including school boards and city councils.

Indeed, for years, the Supreme Court has been slowly but steadily eroding the robustness of Section 2, for example by imposing compactness and demographic requirements that act in tandem to make it harder for plaintiffs to win relief from racially discriminatory maps in the diverse, multi-ethnic communities where Americans increasingly live.

And, even where Section 2 plaintiffs succeed, as Alabama and Louisiana illustrate, courts often use the so-called Purcell principle and the excuse of an upcoming election to delay the redrawing of maps, effectively giving discriminatory line drawers one free election and term of office to enact policy. While districts may ultimately be struck down, people must live with the consequences of elections under illegal maps. In short, even if the Supreme Court didn’t do as many feared and further whittle away at the Voting Rights Act, the status quo for voters, and minority voters in particular, remains deeply inadequate.

While Milligan should be celebrated as a win for fair representation, it cannot be an excuse for congressional inaction. This month marks the 10-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder, a decision that gutted another key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In the decade since, Congress has tried and repeatedly failed to overcome legislative inertia to respond. Section 2 lives to fight another day, but the provision by itself is not—and never has been—enough. It is well past time to not only restore but strengthen the Voting Rights Act for a 21st-century America. Nothing less than the future of the country’s emerging multiracial democracy is at stake. Congress must act.

- With Support of Just One Republican, House Passes 'Historic' Bill to Restore and Expand Voting Rights ›

- 'Huge Surprise' as US Supreme Court Declines to Further Gut Voting Rights Act ›

- Blaring Quiet Part Out Loud, GOP Lawyer Admits to Supreme Court That Easier Voting Puts Republicans at 'Competitive Disadvantage' ›