I have for decades been assuring both colleagues and comrades that the climate negotiations are not a sick joke, that “COP” is not short for “Conference of Polluters,” that the negotiations matter. The argument has become easier to make as more people have come to see the implacable necessity of an international way forward. As imperfect as the COP process is, a world without multilateral climate negotiations would be far worse.

Still, there comes a time, amid the floods and the firestorms, when even the practiced realism of seasoned observers must break down. This time didn’t quite come at COP29, though it came close. As Martin Wolf put it in the Financial Times, “the assessment has to lie between failure and disaster—failure, because progress is still possible, or disaster, because a good agreement will now be too late.”

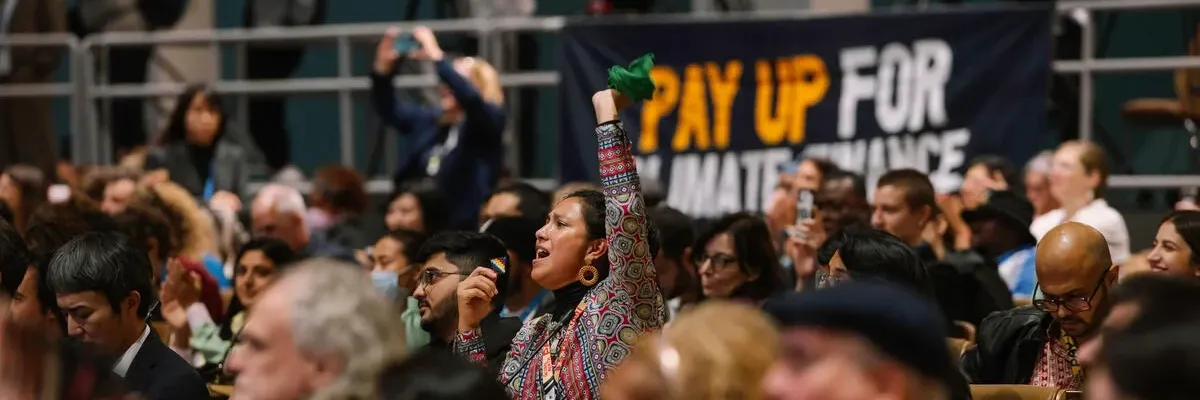

The climate problem demands an earnest and cooperative international response, but Baku instead saw the Global North present the Global South with a “grim ultimatum”—agree to an inadequate offer of support or risk the collapse of the only international process where it has significant voice and influence. By its end, the Global South had been forced to accede. With the clap of the president’s gavel, and despite a broad push to assert that “no deal is better than a bad deal,” it got a very bad deal indeed.

COP29 really did have a silver lining. It focused the climate finance debate and pushed it to center stage.

There was also action on the emissions trading front, where the rules were finally nailed down. But the rules are pretty bad and the deal is more likely to generate a flood of illusory offsets than a flood of quality investment. Also, and importantly, neither carbon trading in particular nor private finance in general can honestly be expected to entirely finance a successful climate transition.

On the public finance side, the pressure to relitigate the Baku deal, already high, can only increase. The last-minute adoption of the “Baku to Belém Roadmap to $1.3 trillion”—a critical commitment to find a real path forward—is likely to define the COP30 agenda. The problem is that, barring an unanticipated political shift of the first order, the Belém COP, too, will fail to rise to the occasion.

The next year is going to be a big one.

Clarity at Last

Hope, as always, remains. The future is unwritten; we have the technology to save ourselves, and we may yet decide to do so. Also, there’s plenty of money, though like the future it is not evenly distributed. Further, COP29 really did have a silver lining. It focused the climate finance debate and pushed it to center stage. There is now, finally, a deep and widespread understanding of the nature and scale of the international climate finance challenge. Talk today about planetary-scale climate ambition and you’re talking in terms of trillions of dollars a year, and everyone knows it.

Unfortunately, this also means the climate negotiations are now in crisis, because those necessary trillions are not on the table. The Baku agreement is simply not going to give the world’s developing countries the confidence—read “the support”—they need to table a strong new round of climate action pledges in 2025. And, as 1.5°C slips through our fingers, it is becoming ever more difficult to believe that even the weak end of the Paris temperature goal (“well below 2°C”) is slated to be preserved.

Part of the problem at Baku was of course the pall cast by Donald Trump’s reelection. Even negotiators who bitterly resent the traditional U.S. tactics knew that something worse was in the future. Just as importantly, it was no longer possible to imagine that the United States, with its massive share of the world’s capacity, would soon produce any significant fraction of its fair share of the cost of rapid international climate mobilization. The Europeans, certainly, could easily argue that, without the United States on board, no adequately ambitious public finance goal could possibly be met, and that, therefore, they could not possibly acquiesce to one.

But Trump’s importance can be overstated. The Europeans have long hidden behind American intransigence, which was a problem long before the age of Trump. The United States has for years worked to eradicate the United Nations climate framework convention’s foundational commitment to equitable burden-sharing based on “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities,” and the Europeans have never roused themselves to object in any effective way.

And, as always, there is the problem of the fossil fuel industry, which cannot be reduced to the problem of the United States, or even the problem of the Global North. The Saudis in particular, with the aid of the Azeri hosts, reportedly did everything in their power to prevent any Baku statement from reiterating COP28’s call for “transitioning away” from fossil fuels. Further, it became clear in Baku that, as Laurie can der Berg of Oil Change International astutely commented, many rich countries are actively planning for fossil fuel phaseout failure.

That planning began long before Trump’s reelection.

There are many issues entwined within the climate negotiations, and across the board their resolution has been blocked by the lack of adequate climate finance. Inevitably, given that Baku was the long anticipated “finance COP,” it was fated to play a very special role. Given the widespread anger occasioned by Baku’s weak outcome, it’s safe to say that it didn’t deliver.

Still, the climate negotiations are not doomed. It is better to say they are now visibly in a crisis they’ve been in for years. But the distinction makes a difference, and the timing could not be more critical. Unless substantial progress is made by the end of COP30, by November 21, 2025, in Belém, Brazil, we’re going to be in extremely serious trouble.

What Did the Global South Demand and What Did It Get?

By the opening of COP29, the Global South’s negotiators had settled on a demand for $1.3 trillion a year in climate finance, much of it to be provided by the developed countries as non-debt-producing grant-based public finance and the rest of it mobilized via facilitated investments. The size of former amount—the “public finance core” that would be provided—was not universally agreed upon, but agreement was close. The G77 + China negotiating bloc cohered around the figure of $500 billion a year, though a number of negotiators and activists, the Climate Action Network in particular, supported a much larger figure. As for the $1.3 trillion, this would be built upon the core, by layering on investments that were mobilized in one way or another.

Baku saw the agreement of a “new collective quantified goal on climate finance,” which replaces 2009’s old finance goal of $100 billion a year, with a new goal that is nominally $300 billion a year. This sounds like a tripling, but it’s not. As for the $1.3 trillion, look to the future negotiation of the “Baku to Belém Roadmap to $1.3 trillion” and prepare for a fight.

Start with the $300 billion, and its comparison to the old goal of $100 billion. The first thing to note here is that the old goal took years to reach, if it was reached at all. The $100 billion line was finally crossed via a finance package that was 70% loans, many of them non-concessional (market rate) loans that significantly swelled recipient countries’ debt loads. The second is that the Baku promise doesn’t have to be delivered until 2035—which, given the climate emergency, is an eternity—and that during that eternity inflation will have eaten deeply into its value.

Stabilizing the climate quickly enough to prevent global catastrophe is going to be expensive, but that we nonetheless have the money to do so. Or, more precisely, the global rich have the money.

Also, and even more crucially, this nominal $300 billion is absolutely not a “public finance core” that will be met exclusively via grant-based financing. It will rather come “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources,” which is to say that the $300 billion (or whatever is left after inflation) will include not only funding provided by the developed nations, but also any private investment this public funding manages to “crowd in,” and loans both market rate and concessional, and even carbon-offset revenues.

To say this outcome is disappointing is to put the matter diplomatically. As Action Aid’s Brandon Wu explains, “There’s no clarity about how much if any of [the $300 billion] will be public, grant and grant-equivalent finance; it could be loans; it could all be private investment; it could all be MDB [Multilateral Development Bank] finance, it could all amount to basically nothing, in fact.” No wonder that during the final plenary, immediately after the decision text was suddenly gaveled through (the delay was 1.04 seconds, according to the Financial Times), Indian delegate Chandni Raina called the finance target “too little, too distant,” and said her country could not support it. “This document is nothing more than an optical illusion,” she said to cheers and applause.

What Does the Global South Actually Need?

What does the Global South need to rapidly decarbonize, while at the same time pursuing a low-carbon development path? There will never be a single correct answer to this supremely difficult question, for no possible answer is free of political and ethical claims, including claims about development and about the even more fundamental and elusive notion of need.

Needs assessments are possible, but assessing the needs associated with planetary climate stabilization—from mitigation needs to loss and damage needs to just transition needs—is extremely difficult, and costing such needs with any real precision is flat-out impossible. However meticulous a needs assessment process is, it can only be provisional, because the “real” bottom line will depend on how quickly and brutally the impacts of climate change unfold, and how decisively humanity mobilizes to contain them, and how much obstruction the fossil fuel industry erects against this mobilization, and how forgiving the overall climate system turns out to be. None of this is knowable in advance, though the total need is certainly larger than $1.3 trillion.

We do, however, have some useful preliminary estimates.

Most prominently, the “High Level Experts Group,” which has been supporting the U.N. climate finance debate since COP26, does not simply defend the $1.3 trillion figure. It also tells us this is not the end of the story, that total ”projected investment requirement for climate action” would be about $6.3-6.7 trillion per year by 2030, an amount that should be roughly divided between “advanced economies,” China, and other nations. Of this, about $2.3-2.5 trillion would be for emerging and developing countries other than China, and this figure would increase to $3.1-3.5 trillion by 2035.

Also notable is the updated Needs Determination Report recently released by the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance. It pegs “the costed needs” from the latest pledges at $5-7 trillion cumulatively out to 2030, a figure which it annualizes (over the 2020 to 2030 period) as $455 billion to $585 billion a year. This, however, is a very partial calculation, and larger estimates can be found within the same report.

In all this complexity, one text is particularly useful, the “submission” that the Climate Action Network’s Finance Working Group made to the pre-COP29 negotiations. This submission advocates a “public finance core” of $1 trillion a year, and then situates that core within a much “wider mobilization goal” that reflects “historic legacies and ongoing practices of unfair atmospheric carbon budget appropriation,” among other inconvenient realities. Also, the text anchors its $1 trillion headline ask in three key subgoals, and reviews the (still primitive) needs assessment literature to conclude that “developing countries’ international climate finance needs could be at least $400bn for loss and damage, at least $300bn for adaptation, and at least $300bn for mitigation, measured in grant-equivalent terms.”

Annually, of course.

We Have the Money

Let’s take this $1 trillion annual figure, stipulate again that it refers to a public finance core that must come as grants or grant-equivalents, add that this finance is needed immediately, not 2035, and note that—unlike the miserable sums gaveled through in Baku—its provision would be a game changer. Not that $1 trillion a year in core public finance would be enough, not as the equatorial regions of the planet dry and people begin to migrate in real numbers, but it would suffice to establish, or at least allow, robust levels of international trust and cooperation. It would really get things moving.

Where would this kind of money come from? A group of us took up this question in the 2024 Civil Society Equity Review, which was entitled Fair Shares, Finance, Transformation: Fair Shares Assessment, Equitable Fossil Fuel Phaseout, and Public Finance for Just Global Climate Stabilization. Unlike this brief essay, it is long enough to treat the finance challenge in meaningful detail. Its key message is that stabilizing the climate quickly enough to prevent global catastrophe is going to be expensive, but that we nonetheless have the money to do so. Or, more precisely, the global rich have the money, and—one way or another—they’re going to have to pay, as per Foreign Policy’s rather inelegant formulation, to “help fix the planet.”

The Equity Review group is not alone in making this case. But Fair Shares, Finance, Transformation is notable for the deliberate manner in which it lays out the path forward, the way it names and quantifies the barriers to decarbonization, and its careful, explicit distinction between finance sources that are immediately available—or would be, given political and economic reforms—and more fundamental transformations that will require deeper system change.

Strategically, the key issue is the finance sources that are immediately available, so here’s a very quick summary. (See Fair Shares, Finance, Transformation for details and footnotes, and for a discussion of the larger context, which includes the need for deeper and more fundamental changes.)

The place to begin is fossil fuel subsidies. These represent a public finance flow that could be quickly redirected to support the climate transition. This flow can be expressed as either direct public support or “total” subsidies. The former, according to Energy Policy Tracker, reached a record high of $1.7 trillion in 2022, a figure that represents “public financial support for fossil fuels, in the form of subsidies, investments by state-owned enterprises, and lending from public financial institutions.” The latter, according to the International Monetary Fund (no hotbed of green socialism), takes a more expansive view of subsidies that includes “undercharging for global warming and local air pollution” and estimates total fossil fuel subsidies at $7 trillion a year.

There are also targeted financial mechanisms already at hand. For example, a reinvention of the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights, which after decades of discussion is only now getting real attention, could very rapidly yield $500 billion in concessional loans, while financial transaction taxes, even at low tax rates, would yield considerable revenues. One proposal calls for a levy of 0.05% to be applied to various domestic and international financial transactions involving stocks, bonds, and currency. In 2011, the estimated revenues for such a tax was $600 to $700 billion; at today’s volume of financial transactions, it could easily raise more than $1 trillion.

Whatever happens, pollution taxes are fundamental. First up are frequent flier taxes, which could yield $150 billion a year, and maritime levies, which could bring in $100 billion more. And when we’re ready to tax pollution directly, all sorts of doors would open. Special attention should go to the proposal for a Climate Damages Tax, which could raise $900 billion by 2030 by taxing fossil fuel extraction in the OECD countries. Eighty percent of this, $720 billion, would go to the Loss and Damage Fund, while the rest would be reserved to support the action in the countries where the tax is imposed. The alternative to such an extraction levy is to more heavily tax fossil fuel companies’ profits. The five oil supermajors alone (ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, TotalEnergies, and BP) made over $120 billion of profits in 2023.

Wealth taxes are increasingly central to the finance debate. Exhibit A is the Blueprint for a Coordinated Taxation Standard for Ultra-high-net-worth Individuals commissioned by the Brazilian G20 presidency and prepared by economist Gabriel Zucman. This proposal is notable for its links to Brazil, the COP30 host, and for the precise way it aims to remedy problems with tax systems that rely on income taxes that fail to effectively tax the super-rich. “Let’s agree that billionaires should pay income taxes equivalent to a small portion—say, 2%—of their wealth each year… In total, the proposal would allow countries to collect an estimated $250 billion in additional tax revenue per year.”

Another approach is to cast a wider net, and go straight to a system of globally harmonized national wealth taxes. This approach is exemplified by a recent proposal from the Tax Justice Network for an “international version of Spain’s ‘featherlight’ progressive wealth tax.” Spain’s tax applies a tax of 1.7- 3.5% to the richest 0.5% of the country’s households, a group of about 26.5 million people. If adopted by nations around the world, it would raise about $2.1 trillion a year. The decisive move here is to erase the unfair distinction between “earned wealth” like salaries and “unearned wealth” like dividends, capital gains, and rents, which is obtained by simply owning things and is typically taxed at far lower rates than earned wealth. This erasure would yield so much revenue because the richest 0.5% own a quarter (25.7%) of all wealth.

Finally, there is military spending, the gold standard of wasted economic potential. Military spending diverts massive streams of resources that could be used to stabilize the climate and build the infrastructure of a sustainable world. The wealthiest nations, those in the UNFCCC’s Annex II, are, according to research by the Transnational Institute, “spending 30 times as much on their armed forces as they spend on providing climate finance for the world’s most vulnerable countries.” The United States is responsible for a huge chunk of that military spending, with an official 2025 military budget of $852 billion, but other countries are by no means innocent. China holds second place, with a military budget now estimated at $296 billion a year. Throughout the world, even very poor countries burn significant fractions of their public moneys on the military sector, to the obvious detriment of climate transformation and the well-being of their populations. When added together, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, global military expenditure surged in 2023 to $2.4 trillion, the highest level ever recorded.

There are two takeaways from all this. The first is that there is plenty of money to stabilize the climate system, and to do so well and fairly. The second is that there are plenty of ideas for how to redirect money to the climate transition. The above list is anything but exhaustive, and the best way forward is probably to combine multiple ideas into one flexible, expansive program. Action Aid, in Finding the Finance, put this well, arguing that the way forward is “taking coordinated action globally to introduce a range of new taxes that could raise trillions of U.S. dollars—such as through windfall taxes, wealth taxes, higher tax rates on the income of the top 1%, financial transaction taxes, a range of carbon and climate damage taxes, and taxes on aviation and shipping.”

Who Pays

This may sound defeatist, but it’s time to seriously consider the possibility that there will be no finance breakthrough, that neither the $300 billion that was promised in Baku nor the far larger sum that would allow us to plan an inclusive and civilized transition to a post-carbon world will ever arrive.

This would not be a surprise. Nor would the consequent anger and outrage and bitterness be in any way unexpected, or even unwelcome. But, having said this, is it permissible to wonder if they would suffice? The question is necessary after Baku, which followed Dubai’s call to “transition away” from fossil fuels. Baku should by all rights have marked a deepening of that effort, but instead the fossil fuel industry, led by the Saudis, was able to leverage the more-than-justified frustration and bitterness of the Global South to ensure that the Dubai call was not even reiterated.

What’s the lesson here? The best answer may simply be that, even as we fight for finance, we have to remember that finance isn’t everything, and that it’s dangerous to believe it is. It is not even exactly the case that finance is a precondition of rapid decarbonization. The truth is rather that economic and developmental justice is a precondition of rapid decarbonization, and that we are being forced by our strange times and dire circumstances to take international finance as a proxy for justice. In some cases—the fossil phaseout comes to mind—we would be better off insisting on the real thing.

Baku cast a bright and unforgiving light on the political vise within which we are trapped. On the one hand we’re out of time, and mitigation—decarbonization—must be our top priority. On the other hand, rapid decarbonization is simply not going to be possible without a great deal of economic justice. Think of the Global South’s overwhelming international debt, which can never be repaid. Think of the massively unbalanced and unsustainable international trading system. Think of the planetary divide between the rich and the poor, and how the rich exploit it at every turn.

Even if, as many believe, decarbonization is the essential core of the climate challenge, it is difficult, amidst today’s crumbling political order, to believe that any sufficiently rapid climate stabilization is possible in a world where adaptation, loss and damage, and just transition challenges—all of them pillars of the solidarity agenda—are left almost entirely unfunded. Yet that is exactly where we are today.

Again, there is plenty of money. The question is how to convert some of it—say, a trillion dollars a year—into grant-based public finance, so that it can be used to provision not only an accelerated mitigation effort, but also the equity agenda—the solidarity agenda and the fair-share agenda—that will have to accompany it. It’s a more than challenging prospect, particularly given that the finance battle must be fought, and won, among the rich, most of whom reside in the Global North, which is currently beset by an exterminist strain of right-wing nationalist populism.

The Washington Postfrankly reported that Baku was “blasted” by the negotiators and activists of the Global South. Then it found space for this:

Taxpayers in wealthy countries will ultimately foot much of the bill for the finance deal. Negotiators from rich nations had to consider the possibility of voters’ resistance to a high amount, especially in the European Union, where farmers have held recent protests against climate regulations, and the United States, where Trump could refuse to send more climate aid overseas.

In an email, Rep. August Pfluger (R-Texas), who led a delegation of House lawmakers to COP29, called the final agreement a “horrible deal.”

“China, the world’s largest polluter, self-identifies as a ‘developing country,’” Pfluger said. “The last thing we need is to be shackled by another harmful, America-last climate pipe dream.”

There’s the problem, and the misery, right there.

Baku can be read—and is being read, within the climate left—as a final repudiation, by the rich countries, of the obligation to do their fair share they took on when they signed the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. I can see the logic here, but I don’t think it’s quite right. The equity battle is anything but over, and it cannot be plausibly repudiated. But the equity battle will also not be won in strict North/South terms.

Looking back over financing options sketched above, I see a way forward, one in which we open the strategic lens, not by talking less about the injustice of the North/South world, but by talking more about the injustices of the rich/poor world. Think, if you will, of the “Baku to Belém Roadmap to $1.3 trillion,” and the challenge to contrive an effective campaign strategy around it. Think, in particular, about the spectrum defined by pollution and extraction taxes on one side, and wealth taxes on the other, which the Climate Tax Justice groups have taken to calling “solidarity levies.” Think about the fact that both pollution taxes and wealth tax are essential, and that they can be imposed nationally and harmonized globally.

The Global South needs real climate finance, and plenty of it. But what if, instead of continuing to insist that this finance will eventually come from the Global North, we admit that there’s only one place to get it: from the global rich. While most of them live in the Global North, some of them don’t. There are now 1,050 billionaires in the United States and 304 in China. We want a solidarity levy on the former group, absolutely, but are we really going to get one without taxing the latter as well?

There were many pre-COP29 finance debates. Last year, during one of them, it became all but impossible to avoid references to a paper by Andrew Fanning and Jason Hickel that argued that the United States—even if it pursues an ambitious emissions reduction trajectory—will by 2050 owe the countries of the Global South something like $200 trillion, as compensation for its historic over-appropriation of the atmospheric commons. It’s a stunning number, and even if it’s only somewhat true, it makes a stunning point.

The “Why Trump Won” debate in the United States is also throwing up some stunning numbers. In this illuminating comment by American historian Heather Cox Richardson, she cites research showing that, had the comparably equitable income structure of post-World War II America to 1974 held steady through 2020, the annual income of American workers below the 90th percentile would by 2018 have been $2.5 trillion higher than it actually turned out to be.

This means that between 1975 to 2018, “the difference between the aggregate taxable income for those below the 90th percentile and the equitable growth counterfactual totals $47 trillion.” Extend the trend ($2.5 trillion a year in shifted income) to 2024 and you arrive at the present: Since 1975, the richest 10% of Americans and especially the richest 1% have taken $60 trillion from the poorest 90%.

Sixty trillion dollars is not $200 trillion, but it’s not peanuts either. We would be fools to ignore it, in favor of a vision of global economic justice that identifies the Global North as the only significant barrier to honest hope. It is, certainly, a keystone barrier, but so too are the global rich, and they well deserve their fair share of the vilification.

The who pays question is one of the oldest on the climate equity agenda. It’s time to answer it properly.