SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

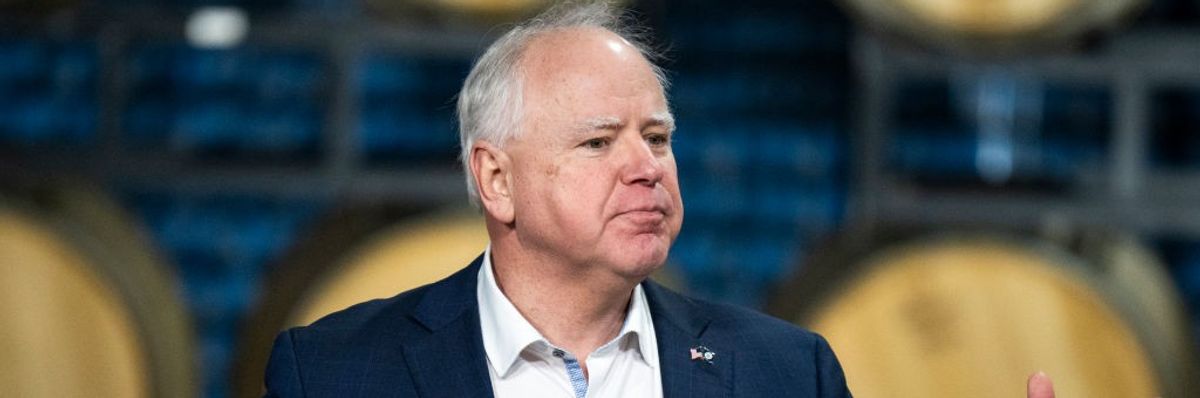

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz speaks about funding for the I-535 Blatnik Bridge before a visit by U.S. President Joe Biden at Earth Rider Brewery on January 25, 2024 in Superior, Wisconsin.

Before Walz was chosen the last thirteen people to grace the Democratic ticket were lawyers. And a union member to boot? Never.

In October of 1874, Arthur Latham Perry, a Williams College professor and one of the most prominent economists of his day journeyed west of the Missouri River for the first time in his life. The occasion of his trip was an invitation to address the Nebraska State Fair and its audience of farmers. Perry began his speech by noting that for every 150 farmers in America, there was one lawyer. He went on to say “I can count you one hundred of these lawyers, who have exerted more practical influence in the states and in the nation” than all of America’s farmers combined. “There is no objection to raise to lawyers; they are a useful class of men,” Perry continued, “but there is decided objection to allowing a mere handful of them, representing a mere handful of clients, to shape and mold the policy of” an entire nation.

I happened to be reading Perry’s speech as part of research for a book the day before Vice President Kamala Harris chose Minnesota Governor Tim Walz to be her running mate. For a mainstream media obsessed with firsts it was surprising that lost in the news of the choice and the horse-race handicapping that inevitably followed was the number of impressive firsts Walz represents. Tim Walz, unlike Vice-President Harris, President Biden, Hillary Clinton, Tim Kaine, Barack Obama, John Kerry, John Edwards, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Michael Dukakis, Lloyd Bentsen, Walter Mondale, and Geraldine Ferraro is in fact, not a lawyer. Not since Jimmy Carter led the ticket in 1980 have Democrats not nominated a lawyer for national office.

Before Walz was chosen the last thirteen people to grace the Democratic ticket were lawyers. High statistical analysis is all the rage in American political entertainment these days, so let’s play with some numbers. Lawyers make up roughly .4% of the American population. Given those odds if you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts. Or to put it in more colloquial terms, for every time you expect that outcome to occur, you might also expect to win the Powerball jackpot at least three times and probably four.

If you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts.

Walz’s not being a lawyer—from here on we will refer to this as his alawyerness—is not unrelated from another “first” and statistical anomaly in American politics that Walz represents. He is a union member, the first as far as I can tell, to ever grace a Democratic Party ticket. Union membership has of course risen and fallen dramatically in the last hundred years, with a high of nearly 36% of American workers in 1953 falling to a record low of only 10% last year. I’ll leave the truly sophisticated statistical analysis to a soothsaying Nate (to be named later). Nevertheless, we probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924. Indeed, given that the national party has been much more closely associated with the interests of organized labor during the last century, one could extrapolate an even higher likelihood.

Statistical absurdities aside, there’s a lot contained in these two firsts about Walz and the history of the national Democratic Party ticket. There are stories to be told about why the political party that is at least a bit more devoted to the interests of working Americans would repeatedly put lawyers at the top of its ticket when Americans trust people like nurses and teachers at least three times as much. Stories to be told about why law school is a pathway to political prominence when union shop stewardship or agricultural cooperative leadership are not. Stories about the kinds of people who set their sights on politics from a young age versus those who come to politics out of their workplaces and communities. Stories about the different interests those different kinds of people tend to represent. Stories about the milieus elite private university graduates tend to inhabit and those that public school and state college graduates tend to inhabit. Stories about what kinds of policies the Democratic Party might pursue if its most prominent leaders were nurses, bus drivers, social workers, pipefitters, firefighters, sanitation workers, farmers, teachers, coaches, and union members. And there are lots of stories to be told about the influence of money versus real democratic constituencies in Democratic Party politics.

We probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924.

Now, as Perry told those Nebraska farmers many decades ago, nothing against lawyers. But Walz’s alawyerness and his union membership, his career as a teacher, coach, and national guardsman, suggest a path forward for everyday Democrats who hope to build a real majority to enact public goods like universal childcare, family leave, health care, and high-quality, well-funded education while also protecting reproductive rights, voting rights, and guaranteeing every working American a wage on which they and their families can live on with a modicum of security.

That path has nothing to do with Walz’s “folksy” charm or any other of the countless adjectives that national commentators use to describe him. Adjectives that give away just how exotic his alawyerness and union membership are to those who assume that law school and elite universities provide a birthright to political leadership in the 21st Century Democratic Party. Walz’s newfound prominence and the statistical anomaly that his appearance on the Democratic Party ticket represents should serve as a reminder.

The reminder should be that what the late Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone used to call the democratic wing of the Democratic Party is made up not of lawyers, hedge fund managers, tech gurus, and media elites, but rather of people who come to politics from their everyday experiences and concerns in their workplaces and communities and who—statistically speaking of course-- can meaningfully represent the interest of their fellow workers and neighbors.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In October of 1874, Arthur Latham Perry, a Williams College professor and one of the most prominent economists of his day journeyed west of the Missouri River for the first time in his life. The occasion of his trip was an invitation to address the Nebraska State Fair and its audience of farmers. Perry began his speech by noting that for every 150 farmers in America, there was one lawyer. He went on to say “I can count you one hundred of these lawyers, who have exerted more practical influence in the states and in the nation” than all of America’s farmers combined. “There is no objection to raise to lawyers; they are a useful class of men,” Perry continued, “but there is decided objection to allowing a mere handful of them, representing a mere handful of clients, to shape and mold the policy of” an entire nation.

I happened to be reading Perry’s speech as part of research for a book the day before Vice President Kamala Harris chose Minnesota Governor Tim Walz to be her running mate. For a mainstream media obsessed with firsts it was surprising that lost in the news of the choice and the horse-race handicapping that inevitably followed was the number of impressive firsts Walz represents. Tim Walz, unlike Vice-President Harris, President Biden, Hillary Clinton, Tim Kaine, Barack Obama, John Kerry, John Edwards, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Michael Dukakis, Lloyd Bentsen, Walter Mondale, and Geraldine Ferraro is in fact, not a lawyer. Not since Jimmy Carter led the ticket in 1980 have Democrats not nominated a lawyer for national office.

Before Walz was chosen the last thirteen people to grace the Democratic ticket were lawyers. High statistical analysis is all the rage in American political entertainment these days, so let’s play with some numbers. Lawyers make up roughly .4% of the American population. Given those odds if you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts. Or to put it in more colloquial terms, for every time you expect that outcome to occur, you might also expect to win the Powerball jackpot at least three times and probably four.

If you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts.

Walz’s not being a lawyer—from here on we will refer to this as his alawyerness—is not unrelated from another “first” and statistical anomaly in American politics that Walz represents. He is a union member, the first as far as I can tell, to ever grace a Democratic Party ticket. Union membership has of course risen and fallen dramatically in the last hundred years, with a high of nearly 36% of American workers in 1953 falling to a record low of only 10% last year. I’ll leave the truly sophisticated statistical analysis to a soothsaying Nate (to be named later). Nevertheless, we probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924. Indeed, given that the national party has been much more closely associated with the interests of organized labor during the last century, one could extrapolate an even higher likelihood.

Statistical absurdities aside, there’s a lot contained in these two firsts about Walz and the history of the national Democratic Party ticket. There are stories to be told about why the political party that is at least a bit more devoted to the interests of working Americans would repeatedly put lawyers at the top of its ticket when Americans trust people like nurses and teachers at least three times as much. Stories to be told about why law school is a pathway to political prominence when union shop stewardship or agricultural cooperative leadership are not. Stories about the kinds of people who set their sights on politics from a young age versus those who come to politics out of their workplaces and communities. Stories about the different interests those different kinds of people tend to represent. Stories about the milieus elite private university graduates tend to inhabit and those that public school and state college graduates tend to inhabit. Stories about what kinds of policies the Democratic Party might pursue if its most prominent leaders were nurses, bus drivers, social workers, pipefitters, firefighters, sanitation workers, farmers, teachers, coaches, and union members. And there are lots of stories to be told about the influence of money versus real democratic constituencies in Democratic Party politics.

We probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924.

Now, as Perry told those Nebraska farmers many decades ago, nothing against lawyers. But Walz’s alawyerness and his union membership, his career as a teacher, coach, and national guardsman, suggest a path forward for everyday Democrats who hope to build a real majority to enact public goods like universal childcare, family leave, health care, and high-quality, well-funded education while also protecting reproductive rights, voting rights, and guaranteeing every working American a wage on which they and their families can live on with a modicum of security.

That path has nothing to do with Walz’s “folksy” charm or any other of the countless adjectives that national commentators use to describe him. Adjectives that give away just how exotic his alawyerness and union membership are to those who assume that law school and elite universities provide a birthright to political leadership in the 21st Century Democratic Party. Walz’s newfound prominence and the statistical anomaly that his appearance on the Democratic Party ticket represents should serve as a reminder.

The reminder should be that what the late Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone used to call the democratic wing of the Democratic Party is made up not of lawyers, hedge fund managers, tech gurus, and media elites, but rather of people who come to politics from their everyday experiences and concerns in their workplaces and communities and who—statistically speaking of course-- can meaningfully represent the interest of their fellow workers and neighbors.

In October of 1874, Arthur Latham Perry, a Williams College professor and one of the most prominent economists of his day journeyed west of the Missouri River for the first time in his life. The occasion of his trip was an invitation to address the Nebraska State Fair and its audience of farmers. Perry began his speech by noting that for every 150 farmers in America, there was one lawyer. He went on to say “I can count you one hundred of these lawyers, who have exerted more practical influence in the states and in the nation” than all of America’s farmers combined. “There is no objection to raise to lawyers; they are a useful class of men,” Perry continued, “but there is decided objection to allowing a mere handful of them, representing a mere handful of clients, to shape and mold the policy of” an entire nation.

I happened to be reading Perry’s speech as part of research for a book the day before Vice President Kamala Harris chose Minnesota Governor Tim Walz to be her running mate. For a mainstream media obsessed with firsts it was surprising that lost in the news of the choice and the horse-race handicapping that inevitably followed was the number of impressive firsts Walz represents. Tim Walz, unlike Vice-President Harris, President Biden, Hillary Clinton, Tim Kaine, Barack Obama, John Kerry, John Edwards, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Michael Dukakis, Lloyd Bentsen, Walter Mondale, and Geraldine Ferraro is in fact, not a lawyer. Not since Jimmy Carter led the ticket in 1980 have Democrats not nominated a lawyer for national office.

Before Walz was chosen the last thirteen people to grace the Democratic ticket were lawyers. High statistical analysis is all the rage in American political entertainment these days, so let’s play with some numbers. Lawyers make up roughly .4% of the American population. Given those odds if you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts. Or to put it in more colloquial terms, for every time you expect that outcome to occur, you might also expect to win the Powerball jackpot at least three times and probably four.

If you were to draw from a hat lawyers and non-lawyers the chances of coming up with lawyers thirteen times in a row would be one time every 670,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 attempts.

Walz’s not being a lawyer—from here on we will refer to this as his alawyerness—is not unrelated from another “first” and statistical anomaly in American politics that Walz represents. He is a union member, the first as far as I can tell, to ever grace a Democratic Party ticket. Union membership has of course risen and fallen dramatically in the last hundred years, with a high of nearly 36% of American workers in 1953 falling to a record low of only 10% last year. I’ll leave the truly sophisticated statistical analysis to a soothsaying Nate (to be named later). Nevertheless, we probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924. Indeed, given that the national party has been much more closely associated with the interests of organized labor during the last century, one could extrapolate an even higher likelihood.

Statistical absurdities aside, there’s a lot contained in these two firsts about Walz and the history of the national Democratic Party ticket. There are stories to be told about why the political party that is at least a bit more devoted to the interests of working Americans would repeatedly put lawyers at the top of its ticket when Americans trust people like nurses and teachers at least three times as much. Stories to be told about why law school is a pathway to political prominence when union shop stewardship or agricultural cooperative leadership are not. Stories about the kinds of people who set their sights on politics from a young age versus those who come to politics out of their workplaces and communities. Stories about the different interests those different kinds of people tend to represent. Stories about the milieus elite private university graduates tend to inhabit and those that public school and state college graduates tend to inhabit. Stories about what kinds of policies the Democratic Party might pursue if its most prominent leaders were nurses, bus drivers, social workers, pipefitters, firefighters, sanitation workers, farmers, teachers, coaches, and union members. And there are lots of stories to be told about the influence of money versus real democratic constituencies in Democratic Party politics.

We probably could have expected a union member to have joined the Democratic ticket at least five or six times since 1924.

Now, as Perry told those Nebraska farmers many decades ago, nothing against lawyers. But Walz’s alawyerness and his union membership, his career as a teacher, coach, and national guardsman, suggest a path forward for everyday Democrats who hope to build a real majority to enact public goods like universal childcare, family leave, health care, and high-quality, well-funded education while also protecting reproductive rights, voting rights, and guaranteeing every working American a wage on which they and their families can live on with a modicum of security.

That path has nothing to do with Walz’s “folksy” charm or any other of the countless adjectives that national commentators use to describe him. Adjectives that give away just how exotic his alawyerness and union membership are to those who assume that law school and elite universities provide a birthright to political leadership in the 21st Century Democratic Party. Walz’s newfound prominence and the statistical anomaly that his appearance on the Democratic Party ticket represents should serve as a reminder.

The reminder should be that what the late Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone used to call the democratic wing of the Democratic Party is made up not of lawyers, hedge fund managers, tech gurus, and media elites, but rather of people who come to politics from their everyday experiences and concerns in their workplaces and communities and who—statistically speaking of course-- can meaningfully represent the interest of their fellow workers and neighbors.